Medieval India is often thought of as an unchanging utopia or a brutal dystopia where the powerless had little to no voice. Nothing could be further from the truth. Protest and dissent existed, often expressed through devotional poetry. This is the story of one of the medieval period’s most powerful protest movements.

This movement battled caste proscriptions; promoted women’s agency; worshipped the god Shiva with meat, onion curries, and other dietary no-nos; and even toppled one of India’s mightiest empires. Called the Lingayats or Virashaivas, their descendants still comprise one of the most powerful voting blocs of Karnataka. How did such a revolutionary community actually form in medieval India, and was it able to achieve its goals?

Revolutionary origins

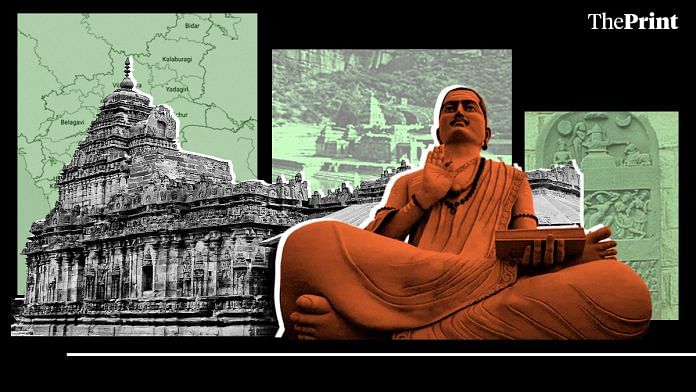

In the late 12th century—a time of massive political and social churn, as we’ve seen in earlier columns—the grandest polity of the Deccan was crumbling. This was the empire of the Chalukyas of Kalyana (present-day Basavakalyan), a glittering city in northern Karnataka. For nearly 200 years, the Chalukyas had dominated the Deccan Plateau, raiding present-day Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh and fighting apocalyptic wars with the Chola empire.

The military successes of the Chalukyas created a wealthy temple-building aristocracy, but also a massive, exploited working class—potters, weavers, cleaners, cowherds, watchmen. According to Lingayat legend, members of these groups began to compose brief, highly emotive poems to Shiva called vachanas. Earthy, humble, and lacking the literary pretensions of the court, they spread rapidly. The Chalukya emperors, meanwhile, had been toppled in a coup by the Kalachuri aristocratic family, closely linked to the orthodox Brahmins of the city of Kalyana.

A young, gifted Brahmin called Basava was one of the Kalachuri king’s ministers. Influenced by popular vachanas, he set up a great structure in Kalyana, the “Hall of Experience” or Anubhava Mandapa. This drew to it the brightest vachana poets of the day such as Mahadevi Akka, a female renunciant who had abandoned her husband and wandered the world naked, clothed only in her hair. Here, they eagerly sang to Shiva, debated theology, and forged a radical new social alliance, calling themselves Shiva’s Heroes (Virashaivas). Shiva’s Heroes, according to later tradition, denounced the temples of the rich, denied the practice of untouchability, and sometimes even denied the authority of the Vedas. Here is one of Basava’s most famous poems, translated by AK Ramanujan in Speaking of Śiva (1973).

“The rich

Will make temples for Śiva

What shall I,

A poor man,

Do?

My legs are pillars,

The body the shrine,

The head a cupola of gold.

Listen, O lord of the meeting rivers,

Things standing shall fall, but the moving ever shall stay.”

But disaster came when Shiva’s Heroes conducted a marriage between a Dalit man and a Brahmin woman. The Kalachuri king, prompted by the city’s Brahmins, expelled the community, scattering them across the Deccan. But the Heroes had grown too popular already—they assassinated the king, prompting social strife, riots and crisis in Kalyana, and the fall of the glittering imperial capital. To this day, “Ketittu Kalyana”—Kalyana is Wrecked—is still used occasionally to express disaster in Kannada.

This is the legend that Lingayats tell of themselves today, after many centuries of storytelling. But a text written by a Lingayat poet just 60 years after their foundational crisis tells a somewhat different story—with shocking views on women’s agency, social identity, and religious rivalry.

Also read: Not Manusmriti, British—caste system in medieval Tamil Nadu solidified after Cholas fell

Unexpected histories

In his 2018 book, Śiva’s Saints: The Origins of Devotion in Kannada According to Harihara’s Ragaḷegaḷu, Gil Ben-Herut analysed the Ragaḷegaḷu, probably the earliest written text of the Lingayat community. The poet Harihara, surprisingly, makes no mention of the “Hall of Experience” and actually claims that Basava conducted communal worship of Shiva in a temple—in his private palace!

But perhaps the poet’s most surprising characters are women, possibly based on actual historical figures. Vaijakavve, a devout Shaivite, is forced by her family to marry a Jain. One day, she gives food meant for Jain mendicants to Shaivites instead. Her husband, furious, beats her but repents when confronted by other Jains. Vaijakavve then appears and opens the local Jain temple, revealing that a Shiva linga had magically appeared there overnight. In a move completely against Brahmin orthodoxy, she personally converts the community into Shaivism. Then there’s the story of Mahadevi Akka, the nude, wandering mendicant, whose devotion to Shiva drives her to leave her husband—absolutely unthinkable for most medieval women.

Harihara’s depiction of Nimbavve, another female devotee, is perhaps his most shocking. (Verses 150–195 of the Nimbavve Ragaḷe). While still young, Nimbavve loses her entire family. Then, destitute, she becomes a domestic worker. After being propositioned by a Shaivite mendicant, she decides to serve the community through intimate union with male devotees. What could this possibly mean? As Ben-Herut notes, perhaps it was believed that all deeds serving this new, fervently devotional Shaivite community—donations of food, wealth, even sex—were to be celebrated. Once you were part of this group, you could bend all the rules in the service of Shiva, whether gender roles or even caste norms.

Examples abound. In Book 10 of the Basaveśvaradevara Ragaḷe, the saint Basava eats with Dalit Shaivites. Dalit Shaivites also educate themselves in the Vedas and defeat Buddhists in debate. (This is almost an exact inversion of Dalit politics today, a sign of how religious communities are constantly changing). Meanwhile, non-Shaivites are excoriated. Basava himself calls royal Vaishnavite Brahmins “untouchable”, and Jains are assaulted or even outright massacred. Later Lingayat texts, such as the 13th century Basava Purana, sing of many saints who attacked and destroyed Jain temples.

Religion and revolution

Perhaps the early Lingayat community holds lessons for us today. This medieval movement was a social coalition, which accepted new groups into the fold and created a new identity, bringing together all who worshipped Shiva. To do so, they were more than willing to break away from some norms. Women were allowed more autonomy (provided they were Shaivites). Non-Brahmin groups had their traditions respected and brought into mainstream worship (provided they were Shaivites). But to tighten their own group identity, Harihara and other early Lingayat poets created an “other”. Which is to say, anyone who was not Shaivite. Progress and emancipation was for “us”, not for “them”.

Ultimately, the medieval community was unable to leverage its ideas into real political power. Instead, Lingayats evolved into a relatively amorphous, exclusive social group. In subsequent centuries, it was Vaishnavism that became the Deccan’s premier imperial religion, building a massive base of popular support, pilgrimage sites, and monastic networks. In historical terms, it’s only recently, thanks to intensive political lobbying and consolidation around priestly lineages, that Lingayats have emerged as a major force in Karnataka’s elections.

We cannot judge the people of the past, but we can observe, in realtime, that modern community-building follows similar patterns. In India’s majoritarian politics today, “insiders” are offered equality and dignity, while reviled “outsiders” are used to define the community. As long as progress and emancipation are constrained by an arbitrary line between “us” and “them”, history will only continue to repeat itself.

Note: Harihara does not actually refer to the Lingayat community by their present-day name, or even as Virashaivas. He prefers the more amorphous term sharana, which in his usage approximates “saint”. For ease of reading, “Lingayat” in this article generally refers to the medieval sharana community and not to the present-day Lingayat social group.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Original idea of Lingayat community failed. One of lingayat friend identify himself as Reddy and another person is proud lingayat (caste supermist)

Being from the lingayat community… I can attest to the fact that majority of Lingayats don’t even know the intricate details of lingayat history and the essence of the sect itself. In fact today lingayat community and people because of not getting a seperate recognition like jains, consider themselves to be part of so called upper caste, which is sad when you know how inclusive and egalitarian this movement was at it’s inception. Thank you anirudh for this article.