When Russian President Vladimir Putin cited the ‘precedent’ set by the United States’ use of Little Boy and Fat Man—the nuclear missiles dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945—the possibility of witnessing another nuclear attack didn’t appear so distant.

In International Relations (IR) literature, what Putin said is part of what we know as nuclear signalling, also known as crisis signalling—a threat of nuclear weapon use uttered by a leader to clarify their intention to an adversary. It can be done through public statements, military exercises involving nuclear weapons, actual nuclear weapon tests, or movement of nuclear weapons, which the adversary is likely to notice.

The distinction between the classical IR understanding of deterrence and compellence, and the Chinese meaning of deterrence is crucial to understand Beijing’s military strategy in Ladakh.

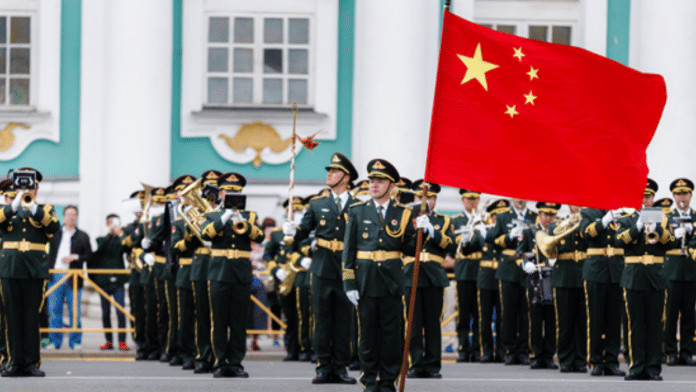

A Chinese angle to deterrence

The Chinese term for deterrence, wēi shè (威慑), differs from the English term. The former combines deterrence and compellence strategies without distinguishing between the two.

Deterrence broadly refers to deterring the opponent from carrying out a threat, and compellence means to compel the opponent to change its behaviour in a conflict or to shape its foreign policy interests. But the Chinese understanding of deterrence mixes these two strategies by using a more active compellence approach through demonstration tests and media psychological warfare.

“Nuclear deterrence is defined as the display of nuclear forces, or the threat of their employment, to shake and awe an adversary or limit and constrain their military activities,” writes Dean Cheng, a researcher on Chinese military and security issues, in NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020

Cheng further explains how the Chinese concept of deterrence differs from the classical IR definition.

“It is notable that Chinese writings explicitly note the importance of not only capability and will, but the communication of both these elements to those whom one wishes to deter,” he adds in his chapter An Overview of Chinese Thinking About Deterrence in the book.

China’s recent investment in improving its nuclear weapons technology, including hypersonic weapons, should be read in the context of this strategy. The Chinese term wēi shè is crucial to conceptualising the intended goal of a missile test or demonstration of nuclear capability. Therefore, China’s missile forces conduct demonstration tests to deter potential aggressors and, at the same time, compel them to change their behaviour.

In the 2005 edition of The Science of Military Strategy, Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) generals Peng Guangqian and Yao Youzhi describe the Chinese understanding of deterrence in the following way: “Deterrence plays two basic roles, one is to dissuade the opponent from doing something through deterrence, the other is to persuade the opponent of what ought to be done through deterrence, and both demand the opponent to submit to the deterrent’s volition.”

China has increased the channels for deterrence signalling with the rise of new media platforms, including WeChat and Weibo. In the context of the traditional crisis signalling scenario, China in the past used the official State media, including The People’s Daily, PLA Daily, and China Daily.

RAND Corporation researcher Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga and others argue that Chinese State media’s use of WeChat and Weibo is far more crucial to understand China’s deterrence signalling.

“In July 2016, after losing an international arbitration case over the international legality of its maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea, Chinese Air Force H-6K bombers flew over Scarborough Shoal, one of the sources of the dispute with the Philippines and broadcast the information first on its official social media account on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter,” writes Beauchamp-Mustafaga et al in the paper titled ‘Deciphering Chinese Deterrence Signalling in the New Era’.

The PLA used a similar approach during the 2017 Doklam stand-off.

“The PLA exercises on the Tibetan Plateau were a demonstration of its capabilities, mobilisation, and readiness, and they were meant to show China’s military superiority, weaken the Indian military’s morale, and deter India’s further aggression,” Beauchamp-Mustafaga et al wrote.

Also read: A flag, a theatre—On Chinese Martyrs’ Day, PLA’s signal to India across Ladakh, Sikkim

Taiwan visit hinted at future actions

The military activity unveiled by Beijing following US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan visit can give us some hints about the type of crisis signalling Beijing can use in the future. The responses to the Pelosi visit began to appear on Chinese social media before the more authoritative State media stepped in to send the message across. The latter increased its use of social media platforms before the launch of full-scale military exercises around Taiwan – including firing of the DF-15 missile by the PLA.

The PLA used social media platforms to send crisis signalling messages during Pelosi’s visit and later made the threats clearer in the official State media articles.

“Their actions are very dangerous and will inevitably lead to serious consequences. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army is on high alert and will launch a series of targeted military operations to counter it, defend national sovereignty and territorial integrity, and thwart external interference and ‘Taiwan independence’ separatist attempts,” said Wu Qian, spokesperson for the Ministry of National Defense on 2 August. The messaging by the ministry first emerged on Weibo and WeChat.

The annual exercises and signalling with weapons tests are becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish from actual crisis signalling. China openly advertises the military exercises in Ladakh and Tibet, and the communication channels have proliferated beyond the official State media. The crisis signalling in the context of Ladakh is far more targeted as compared to Doklam, where Beijing didn’t wholly achieve its objective — but wants to do so with the current stand-off.

Beijing’s strategy in Ladakh appears to be to both deter India’s increasing parity with the construction of new infrastructure projects in the areas and compel New Delhi to accept the new status quo. Another aspect of Beijing’s compellence approach is to make the Narendra Modi government change its behaviour of aligning with the US and the Quad.

When Chinese diplomats say that the India-China border dispute has been ‘normalised’ while the PLA continues to conduct missile tests and military exercises, the strategy is to exert maximum pressure to compel the opponent to accept the terms on the table. There are limitations to what diplomacy can achieve; Beijing is approaching the crisis with a strategic goal vis-à-vis India. Creating the rationale for the dispute over parts of Ladakh region as a ‘sovereignty issue’, mentioned by Chinese State media, can set the precedent for a future conflict.

Reading the signals is critical to deciphering Beijing’s deterrence strategy and the future course of action along the Line of Actual Control.

The research for the column by the author is part of a dissertation submitted to School of Oriental and African Studies, London. The author is a columnist and a freelance journalist, currently pursuing an MSc in international politics with a focus on China from School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. He was previously a China media journalist at the BBC World Service. He tweets @aadilbrar. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)