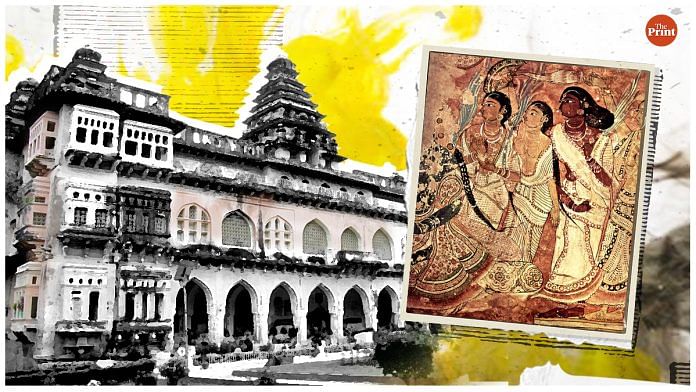

The Vijayanagara Empire. Today, the name conjures up images of tragedy and ruin. From the early 20th century onwards, colonial and nationalist historians have romanticised it as the “last Hindu empire”, either dismissing or distorting its very real cosmopolitanism—and taking attention away from what truly made the 14th to the 16th centuries CE a remarkable era of South Indian history.

Over this time, truly transregional, multilingual empires emerged across the Indian subcontinent. In the process, diverse new elites moved across its landmass: it was not unusual for a Vijayanagara or Deccan Sultanate court to have Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, Marathi and Persian speakers. However, the arrival of new warrior elites also disturbed centuries-old social dynamics. In present-day Tamil Nadu, especially, Vijayanagara’s martial and governing classes inadvertently created chaos and crisis before finally settling into the thriving South Indian societies we are familiar with today.

An era of migration

In her chapter Instability, Opportunity and Innovation, part of the edited volume Abhyudaya, American historian Leslie Orr recently challenged the conventional division of South India’s history into “Hindu” and “Muslim”. Instead, she pointed out, the inscriptional picture of Tamil Nadu reveals that the situation in the 13th century—on the eve of the Delhi Sultanate’s invasions—was quite similar to that of the 14th, when both Delhi and Vijayanagara campaigned in the region. This period of churn continued until a new social formation emerged in the 16th century—nearly 200 years after Vijayanagara rule had established itself in the region.

One of the defining characteristics of the 13th–16th centuries is the movement of people, and the emergence of private property as a powerful economic force. Some migrations had certainly happened even before the 12th century. For example, in the mid to late 11th century, a large number of Tamil-speaking peasant warriors, encouraged by Chola military campaigns, migrated from the areas around present-day Chennai and Kanchipuram into the Kolar region. Here, they acted as a ruling class over a mixed peasantry of Kannada and Telugu speakers, issuing an edict in 1072 CE collectively determining the taxes they would pay to the Cholas.

By the 12th and 13th centuries, however, the picture was reversed. Distinguished Japanese historian Noboru Karashima, who spent his life studying medieval South India, analysed the period in his monumental works, Ancient to Medieval: South Indian Society in Transition, and History and Society in South India: The Cholas to Vijayanagar. Karashima established that hill peoples, who became wealthy by participating in Chola military expeditions, moved into the Coromandel plain, purchasing lands from indebted villages. They, too, used collective organisation to lobby for a high socioeconomic position. Simultaneously, other powers—especially the Hoysala kingdom of southern Karnataka—conquered parts of the Kaveri river valley, bringing with them a Kannada-speaking peasantry. While the Hoysalas later patronised some major Tamil temple centres, the initial decades of their conquest were chaotic. In The Cōḷas, historian KA Nilakanta Sastri shows that they ransacked many shrines and carried off their wealth and idols.

Warrior elites continued to migrate into Tamil Nadu in the next century. In 1311, the Delhi general Malik Kafur caused much chaos through his raids, and a brief, rapacious Sultanate was established in Madurai as well. Isolated from the currents of manpower and horsepower that kept the Delhi Sultanate afloat, the Madurai Sultanate was, in turn, conquered by the new Deccan polity of Vijayanagara in 1371. And in The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara, American historian Burton Stein shows that Vijayanagara, too, brought with it large numbers of Kannada military elites. It also encouraged the migration of Telugu peasant-warriors who settled in the black soil regions of Tamil Nadu, including Salem, Coimbatore, Tirunelveli and Madurai. It was only in the 15th century that the tide of military migration finally slowed.

Also read: How Shiva and Narasimha worship assimilated Adivasis in Andhra Pradesh

Tax, crisis, and collective negotiation

The end of migration did not mean a return to business as usual. Collective negotiation—a tactic first used by landlords—was picked up by many nascent castes in medieval Tamil Nadu. They used it to protect or improve their prospects in difficult times. In the 12th century, writes historian Y Subbarayalu in South India Under the Cholas, cultivators of the Vellala community negotiated with their Brahmin landlords to reduce levies and to confirm their higher status over artisans. In other areas, artisan collectives, formerly segregated into separate villages, obtained Brahmin recognition as a twice-born caste. This was studied by historian Vijaya Ramaswamy in her paper, Vishwakarma Craftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular India. And as Chola power disintegrated in the 13th century, large coalitions of caste-like groups decided on taxes, security fees, and social hierarchies, as Karashima writes in Ancient to Medieval.

In the 15th century, after generations of warrior migration, a socioeconomic crisis was looming. Stein (Vijayanagara) shows that immigrant Vijayanagara warriors, such as the Saluva dynasty, established fortresses such as Chandragiri in the uplands, and demanded taxes from the plains. Seeking to play a role in the politics of the imperial centre in the Deccan, they were focused primarily on enriching themselves. This is revealed by temple inscriptions spread across the Kaveri delta as well as the northern Coromandel plain. In South Indian History and Society, Karashima studied inscriptions made by the Brahmin assembly at Ukkal (present-day Magaral) in the 15th century and found they were forced to sell their lands to outsiders to meet revenue impositions.

Other Brahmins and Vellalas collaborated with Vijayanagara officials. Some of these officials were locals, while others were immigrants who purchased tax farming rights. These tax farmers could be merciless in trying to recoup their costs. In one case, Karashima points out that the rate of tax went up tenfold from 200 to 2,000 coins a year. The burden of this taxation was often forced upon artisan and trader communities, leading to unprecedented class and caste solidarity. The Valangai (Right-Hand) and Idangai (Left-Hand) caste coalitions, meeting in a series of assemblies throughout the 1420s, complained of the excessive impositions by officials. They came up with their own, more favourable rates and threatened to degrade the caste of any coalition members who complied with royal authority. In other cases, they outright fled in protest. Their cause was soon joined by Brahmins, Vellalas, and Shaivite and Vaishnavite religious orders.

These moves were successful—but only to an extent. The Vijayanagara rulers, faced with a fait accompli, were forced to agree to a lower tax burden. However, as late as the 16th century, there were still scattered instances of over-taxation. Other communities were better off. Collective negotiation was a powerful tool, but some did benefit from Vijayanagara authority. Global trade continued to steadily rise throughout this period, thanks partially to Chinese and European expeditions in the Indian Ocean. This worked in favour of the Kaikkolar weaver community. They asked for—and received—caste privileges from Vijayanagara officials, such as the right to ride a palanquin and blow the conch shell.

Throughout the 16th century, a series of Vijayanagara military men called Nayakas carved out small principalities in Tamil Nadu. The collapse of Vijayanagara power at the end of the century finally levelled the odds, prompting Nayakas and their subjects to reach new accommodations. This would lead to a cultural efflorescence in early modern Tamil Nadu—a dynamic we will explore in future editions of Thinking Medieval.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)