Deep Daan Utsav is celebrated by Neo-Buddhists on the day of Kartik Amavasya as per the Hindi calendar. While it is celebrated across India as ‘Diwali’ or ‘the festival of lights’, its history is a contested one, torn between myth and appropriation. The practices surrounding the festival of lights might seem pan-Indian, but there are multiple historical vantage points from which one can look at Diwali.

Neo-Buddhists claim this day marked the completion of 84,000 stupas by King Ashoka. According to Hindu myth, the day is celebrated to mark the victory of Lord Rama and his return to Ayodhya. The festival is also connected with the agrarian society marking the completion of the Kharif season. The rise of globalisation and the marketisation of festivals have given new meanings to the festivals altogether.

It is important to note, though, that both Deep Dan Utsav and Diwali reflect the historical differences that are marked by a series of contestation and appropriation.

Also read: Ashok Vijaydashmi to Dhola — National archives, central libraries failed Dalit-Bahujan history

What is Deep Daan Utsav?

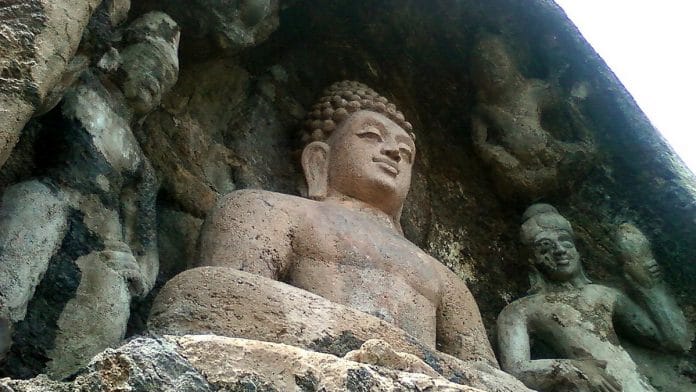

Deep Daan Utsav is the acknowledgement by Neo-Dalit Buddhists of King Ashoka’s effort to revive Buddhism in India. Buddhist history says that after the Mahaparinirvana of Buddha, his relics were distributed among eight kingdoms — Ajatashatru of Magadha, Licchavis of Vaishali, Sakyas of Kapilvastu, Bulis of Allakappa, Koliyas of Ramgram, Brahmins of Vedas, Mallahas of Pawa, and Kushinagar.

King Ashoka brought back these relics to Patliputra. He further ordered the construction of viharas, chaityas, and hospitals in 64,000 different cities to ensure the spread of Buddhism. Dr Balmiki Prasad, in his work Deepvansh, discusses Ashoka’s efforts, particularly in Patliputra and Vaishali where he established a Buddha mahavihar named Ashokaram.

Rahul Sankrityayan discusses the construction of 84,000 sites of Buddhist chaityas, viharas, and stupas. It is said that after the construction was completed, King Ashoka celebrated this day, Karthik Amavasya, as Deep Daan Utsav. It was marked by the lighting of deep or lamps, and giving dana or grain to Buddha Bhikkhus.

Dr Vijay Kumar Trisharan has argued that Deep Daan Utsav, which is now popular as Diwali, was actually a festival of the Mulnivasi, who were Buddhists. He says Brahminical forces appropriated the festival, thereby diminishing the Buddhist ideology. For instance, 64,000 Buddhist preachings were changed to 64,000 yonis, which was one of the many ways in which Deep Daan Utsav was Brahmanised, which helped invent Diwali through myths that sought to counter the Buddhist legacy of King Ashoka. In recent times, the revival of Buddhism by the Bahujan community through its cultural practices is a significant aspect of contesting and resisting Hindu myths with historical facts.

The Bahujan community, which has accepted Buddhism, celebrates this day as Deep Daan Utsav. They lay claim to the authenticity of the festival as Buddhists through Buddha’s last words— “Atta Deepo Bhava“, which means “Be thy own light.” The lighting of deep is, therefore, ingrained within the Buddhist philosophical tradition.

Also read: King Ashoka’s ‘hospitals’ to Rural Health Mission — how the Indian medical system evolved

The everyday practices of contesting histories

The revival of celebration of Deep Daan Utsav is a consequence of the rise of anti-caste consciousness among Bahujan communities. The reworking of myths and re-reading of history are important cultural practices to shed the coyness and indignity that had historically shrouded Bahujans. The works of Jyotirao Phule, such as Gulamgiri, have reflected upon the mythical practices from Hindu scriptural texts to reclaim a dignified identity.

Among Buddhist Bahujan communities, the celebration of Deep Daan Utsav is marked by equal fervour as Diwali. The practices include lighting up houses, listening to Buddhist verses, visiting viharas, donating to Bhikkhus, etc. These practices are attempts by the Bahujans to revive and claim historical glorification. The significance lies in tracing the history of Buddha and Ashoka, which is an anti-caste practice of thinking about a casteless society that Buddhist philosophy discussed.

Within intellectual traditions, the works of Sankrityayan, Bhadant Kaushalyayan, Vincent Smith, Gail Omvedt et al have been significant in discussing the revivalism of Buddhism through these cultural practices. Much of their works are part of the popular narratives as well, which are circulated through booklets, social media, and everyday conversations.

Also read: Black lives mattered to Phule and Ambedkar. They had seen caste discrimination in India

Contemporary practice

The revival of Buddhism, particularly after Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s conversion in 1956, has opened up the space for critically rethinking the contested history. Dr Ambedkar, in his work The Triumph of Brahmanism (Vol 3, pg 275), says, “It has been commonly supposed that the culture of India has been one and the same all throughout history; that Brahmanism, Buddhism, Jainism are simply different phases and that there has never been any fundamental antagonism between them…In the first place, it must be recognized that there has never been such as a common Indian culture, that historically there have been three Indias, Brahmanic India, Buddhist India and Hindu India, each with its own culture.”

The contemporary practice of projecting festivals as homogenised and distanced from contestation is all about eulogising the Hindutva agenda that seeks to disregard historical wrongs. Even within the mainstream discursive practices, the cultural resistance through re-reading of history by the Dalit Bahujan community is largely ignored.

It is significant to note that cultural attributes, like the celebration of a festival, are important reflections on the historical trajectories through which cultures have unfolded. For the Dalit-Bahujan community, festivals are an important aspect of remembrance and rethinking history. The celebration of Deep Daan Utsav roots itself in the Buddhist tradition of Ashoka, something that has been shunned from mainstream historiography, which never acknowledged the contestation between myth and history. The celebration of cultural events are significant social parameters through which contested social history lays itself bare.

Kalyani is a PhD scholar at the Center for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). She tweets at @FiercelyBahujan. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)