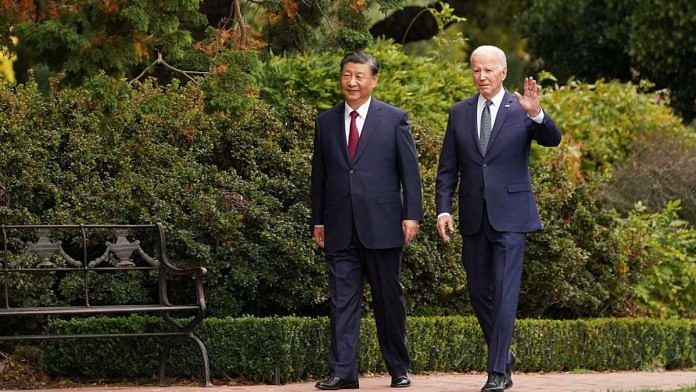

The resumption of leadership-level engagement between two major powers that have been locking horns in recent years has surprised foreign offices across the world. The Biden-Xi summit in San Francisco has set the stage for stabilisation in US-China relations. How did we get to this point, and what does it mean for the future of US-China ties?

Since June 2023, there has been a determined outreach to China with a flurry of US cabinet minister visits to Beijing — starting with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, treasury secretary Janet Yellen, climate envoy John Kerry, and commerce secretary Gina Raimondo. The Pentagon even tried a defence ministers meeting, which was ironically stymied by the US’ own sanctions against the Chinese minister. Then, in October 2023, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi touched down in Washington, a visit that even led to a photo op with Biden at the White House. The message from Washington was loud and clear: comprehensive contact and engagement with the Chinese leadership.

Even the idea of reducing US economic linkages with China, which has gained much momentum in recent years, was being gradually trimmed down and reframed by high-level US pronouncements over the past year.

‘Decoupling’ became ‘de-risking’, which became ‘China+1’. Now, there’s an imminent return to broad economic engagement with the exception of, as US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan put it in April 2023, US controls that “will remain narrowly focused on technology that could tilt the military balance.”

This was meant to include select high technology sectors, like advanced microchips and Artificial Intelligence. The US intends to protect its “foundational technologies with a small yard and high fence.” This still leaves a massive open yard for interdependence. Two-way trade in 2022 was more than $750 billion.

Changing geopolitical context

Until the sudden outbreak of the Ukraine war, the Chinese seemed prepared to allow for strategic competition, that had been declared by the Trump administration and reiterated in more sophisticated rhetoric by the Biden team, to find its natural equilibrium despite the instability and uncertainty that accompanied this process.

Then came the war in Europe in 2022, and the lurking risk of the collective West stumbling into more dangerous military conflicts in Asia. This might have shaped China’s proactive approach toward lowering the temperature in the relations with the US.

China is also adapting to the onset of a multipolar age. The pressure on Beijing had already been alleviated to a large extent, even before this summit. The Western confrontation with Russia over Ukraine had already made the idea of a simultaneous US Cold War or a clash with China a farfetched proposition. As early as spring 2022, the Biden administration was reaching out to Beijing in an attempt to stabilise the Pacific front for a total encirclement and isolation of Russia. That triangular geostrategy failed spectacularly.

The Chinese rebuffed US overtures and waited for better terms. Ironically, the context improved as Russia’s battlefield prowess dramatically turned the tables on NATO with a devastating response to the Ukrainian summer offensive in June 2023. At the geoeconomic level too, the Russia factor had begun to create a disturbing trend for the West. The global majority had rejected the Western narrative on Ukraine and refused to participate in economic containment against Russia, which was causing collateral damage by way of disrupting critical energy, commodity, and agricultural supply chains.

It was the prospect of a truly global power shift, with the ‘Global South’ non-aligned but receptive to deepening ties with non-Western networks such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) that further shaped US incentives for a détente with China. Thus, the stage and conditions were set not as much by China but more by the complex structural changes that received an unexpected impetus from the NATO-Russia confrontation. China finds itself as a beneficiary of this evolving balance of power.

The US establishment and the world know that Washington has lost its global supremacy to envelop the Eurasian heartland in a traditional Cold War 1.0 style grand strategy to bog down its two main great power rivals into a costly game of competition and attrition. The West now seems to have fewer options other than developing a complex relationship with China while choosing to remain locked in an irrational state of confrontation with Russia.

For China, the real upside from San Francisco is that a US-led containment strategy has been neutralised. We are now likely to see a more dampened-down version of competition from the US, restricted to select areas of high technology and regional security in the Western Pacific.

Also read:

Modus vivendi or a tactical pause?

Each side has put forward its own vision for stable and constructive ties while attempting to safeguard its national interests. Biden stated that competition is a reality, but the world expects both sides to “manage competition responsibly to prevent it from veering into conflict, confrontation, or a new Cold War.” Xi called on the US to build together five pillars for bilateral relations: respecting red lines, jointly managing disagreements, advancing economic interdependence, jointly shouldering responsibilities as major countries by coordinating on different issues, supplying public goods and coordinating policy initiatives in different regions and issues, and promoting societal contact.

The debate is still on as to whether this summit achieved a modus vivendi, a great power détente or a tactical pause. Each of these arrangements suggests very distinct types of great power relationships.

A modus vivendi is typically accompanied by a geopolitical accommodation or at least an agreement on the core principles of a future US-China relationship. Some refer to this as a ‘G-2’. But this has not occurred.

The US has still not accepted the emerging world order in terms of multipolarity, nor is it clear how it sees China’s role in the post-unipolar world. It certainly has not accepted China as an equal great power yet. The Chinese, for different reasons, have also not clarified any conception of the world, although they have hinted at changes in world order that are unprecedented. At the same time, Xi proclaimed that there was enough space for both countries to exist and flourish and that China did not seek to “surpass or unseat” the US.

A détente suggests two rivals who recognise that limiting and controlling their rivalry is mutually advantageous. The superpowers discovered this during the Cold War – when the build-up of nuclear and missile forces on both sides had radically transformed the global security environment and the grave risks that uncontrolled competition brought with it.

In the present case of US-China relations, there is the added layer of economic interdependence and inextricably bound-up supply chains that have increased the costs of unrestrained competition. It is the mutual fear of globalisation collapsing into zero-sum policies and blocs that has also prompted both sides to reduce tensions.

A tactical pause is something that two exhausted rivals pursue to allow themselves to address more pressing challenges and priorities. What this arrangement does is interrupt the rivalry for some time, perhaps for several years, before it re-commences.

It would appear we are somewhere between a détente and a tactical pause.

It is interesting what Xi said to Biden: “For China and the United States, turning their back on each other is not an option. It is unrealistic for one side to remodel the other. And conflict and confrontation has unbearable consequences for both sides. Major-country competition cannot solve the problems facing China and the United States or the world. The world is big enough to accommodate both countries, and one country’s success is an opportunity for the other.”

Overall, the Chinese seemed more interested in developing an overarching framework for the evolution of the relationship. In contrast, the US seemed more focused on limiting the prospect of sudden conflict, miscalculations or military escalation in existing West Pacific flashpoints. The US also seemed eager to reverse the deep freeze in high-level engagement. Yet, even these limited US priorities suit China, which still benefits from a less hostile and more predictable US.

What both sides also agree on is providing positive signals and alleviating the uncertainty that was dividing US and Chinese economic actors from pursuing more interdependence. China even announced an ambitious goal of attracting 50,000 students from the US in the next five years. Both sides also provided reassurances on the question of Taiwan, in a way that allowed each side to maintain core policy positions while also stabilising the status quo.

Looking ahead, both countries will continue to bargain on the terms of their relationship in the context of structural competition, a changing relative power balance, and a fluid global order. This is obviously a formidable policy challenge – to find an equilibrium in the relationship with so many moving parts – and one that is further complicated by domestic politics, particularly in the US.

Yet, what remains significant is the eruption of an uncontrollable geopolitical rivalry in the Western Pacific has been arrested by the November summit.

Dr Zorawar Daulet Singh @Z_DauletSingh is a strategic affairs expert and author of several books, including most recently ‘Powershift: India-China Relations in a Multipolar World’. You can follow his work here. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)