The 1990s in India were a time of political flux, marked by a rapid turnover of prime ministers, as well as major electoral and economic reforms under Election Commissioner TN Seshan and PV Narasimha Rao respectively.

One feature of this era was a long line of coalition governments. The Rashtrapati Bhawan was kept busy with no fewer than seven prime ministerial oath-taking ceremonies between November 1990 and March 1998.

Except for Narasimha Rao, who completed his term from June 1991 to May 1996, the other prime ministers had rather short innings. Chandra Shekhar was in office for 223 days (10 November 1990 to 21 June 1991), Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s first term lasted 16 days (16 May to 1 June 1996), and HD Deve Gowda served for 324 days (1 June 1996 to 21 April 1997). The last two years of the decade saw IK Gujral in power for 332 days (21 April to 18 March 1998) and Vajpayee for 573 in his second run as PM (19 March 1998 to 13 October 1999).

Also Read: Emergency’s legacy? How Lok Sabha polls from 1977-1989 changed India’s political landscape

Enter TN Seshan

On 21 May, in the middle of the 1991 Lok Sabha elections, the assassination of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi brought polling to a sudden but temporary halt.

There was a surge in support for the Congress party, according to the India Today-Marg Survey, but it could not achieve an absolute majority, though it was still the largest single party. At this point, the anti-Congress sentiment that had fostered cooperation among opposition parties in 1989 had largely dissipated. President R Venkataraman invited the Congress to form a government, which they accepted. PV Narasimha Rao became the head of this minority government, the first of its kind that lasted a full five-year term.

Interestingly, Rao, who had previously announced his retirement from politics, did not contest the elections, but he accepted the position when he emerged as the consensus candidate of his party. Together with then Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, he is credited with ushering in economic reforms that set the country on a high growth trajectory.

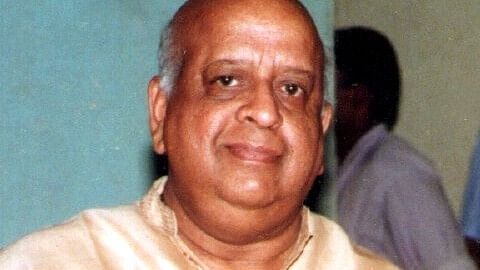

Meanwhile, on the electoral reform front, Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) TN Seshan was making his presence felt. The 1991 polls were his first as CEC, giving him a first-hand experience of the pain points and lacunae plaguing the electoral system. He identified discrepancies between the letter and spirit of the Representation of Peoples Act (RPA) and Article 324 of the Constitution, and the ground reality.

By his own admission, he was given this assignment on the recommendation of his close friend and Harvard mentor Subramanian Swamy, who was the Law Minster in Chandra Shekhar’s cabinet. “I assumed the office when I didn’t know the rules and how the Election Commission operates,” Seshan said in an interview. “I had never conducted an election. I went with two principles: zero delay and zero deficiency.”

During his early days on the job, Seshan identified over 100 common electoral malpractices. These included inaccurate election rolls, improper setting up of polling stations, coercive electioneering, campaigns spending more money than the legal limit, booth capturing, liquor distribution, use of government funds and machinery for campaigning, appealing to voters’ caste or communal feelings, use of places of worship for campaigns, and unauthorised use of loudspeakers and high-volume music.

The first and foremost change was the appointment of election observers from states other than the one facing polls. This was implemented by amending the relevant provisions of the RPA.

Tussles over election reforms

Seshan’s reformative zeal did not always go down well with the Narasimha Rao government. After frequent collisions with the CEC, it decided to make some changes.

In October 1993, the Centre turned the Election Commission into a multi-member body by appointing MS Gill and GVG Krishnamurthy as the other two election commissioners. While Seshan continued as CEC, his powers were curtailed and the initial months of this new arrangement weren’t smooth.

Seshan went to the Supreme Court against this decision, but a unanimous judgment by Justices AM Ahmadi, MK Mukherjee, Jagdish Saran Verma, NP Singh, and SP Bharucha upheld the legality of the Election Commissioner Amendment Act, 1989, adopted on 1 January 1990. This Act turned the commission into a multi-member body in which decisions were to be taken with a majority vote. In effect, the CEC could be overruled.

The next confrontation was about invoking Rule 37 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. This rule would allow postponing or even cancelling any election after 1 January 1995 if the government continued to delay the issuing of photo identity cards. This caused a furore, with epithets like “mad dog” thrown at Seshan and the Supreme Court also rejecting the proposal. But thanks to his insistence, voter ID cards as well as annual electoral roll revisions became essential elements of the election process.

Also Read: Just how staggering is the logistic of conducting Lok Sabha election in India? 1st to 18th

BJP in the reckoning, serial coalitions

The 1996 elections were the first to be held under the multi-member commission. Having been appointed as an election observer, I could see the practical differences on the ground.

The observer’s role included ensuring that no eligible candidate was rejected during nomination filing, overseeing the deployment of Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs), and randomising polling parties to cut out all discretion and bias.

In this election, the BJP improved its score. Capitalising on the Ram Janmabhoomi -Babri Masjid polarisation, it won 161 Lok Sabha seats, making it the largest party in Parliament. This was a first for a non-Congress party, although it secured neither a significant increase in the popular vote nor enough seats to secure a parliamentary majority.

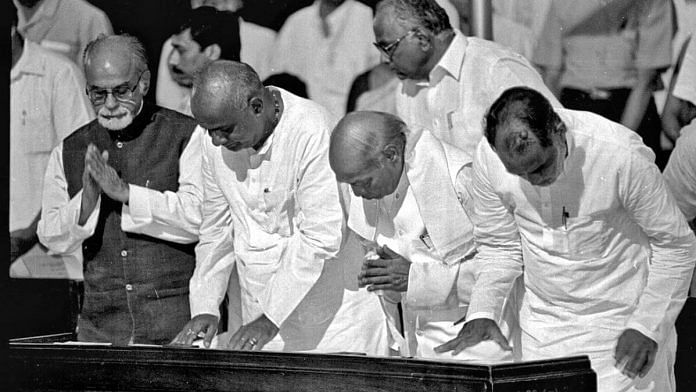

Following the Westminster tradition, President Shankar Dayal Sharma invited Atal Bihari Vajpayee, as leader of the BJP, to form a government. Sworn in on 15 May, the new Prime Minister was given two weeks to prove majority support in Parliament. However, by 28 May, Vajpayee conceded that he could not arrange support from more than 200 of the 545 MPs. He gave a rousing speech and resigned rather than face the confidence vote, ending his two-week government

Subsequently, the Congress, the second largest party, also declined to form the government. Thereafter, CPM leader and West Bengal CM Jyoti Basu was chosen as the consensus candidate of the United Front, but the politburo committed a “historic blunder” and decided not to join the government.

Basu then proposed Janata Dal leader and Karnataka Chief Minister HD Deve Gowda as the candidate for the Prime Minister’s post. Finally, the Janata Dal and a bloc of smaller parties formed the United Front government with external support from the Congress. Gowda resigned on 21 April 1997 due to the withdrawal of the Congress’ support. This paved the way for IK Gujral, who maintained good relations with the Congress, but this too proved to be an unstable arrangement.

In March 1998, Vajpayee was again called in to head the government. In the ensuing months, his leadership during the Kargil War strengthened his and his party’s position, and a confident BJP went in for elections in 1999. The elections saw the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance win 269 seats in the Lok Sabha, along with outside support of 29 MPs of the TDP. The elections gave Atal Bihari Vajpayee the distinction of being the first non-Congress Prime Minister to serve a full five-year term.

Another first in these elections was the deployment of electronic voting machines (EVMs), designed by IIT-Bombay professors AG Rao and Ravi Poovaiah, in a general election. The machines had previously undergone pilot testing in select constituencies of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Delhi. From 2003 onwards, all by-elections and state elections were conducted using EVMs. Encouraged by the success of this, the Election Commission decided to use only EVMs for Lok Sabha elections in 2004.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was Director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)