India’s presence at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s 23rd meeting in Islamabad sent a clear message: there will be no engagement with Pakistan.

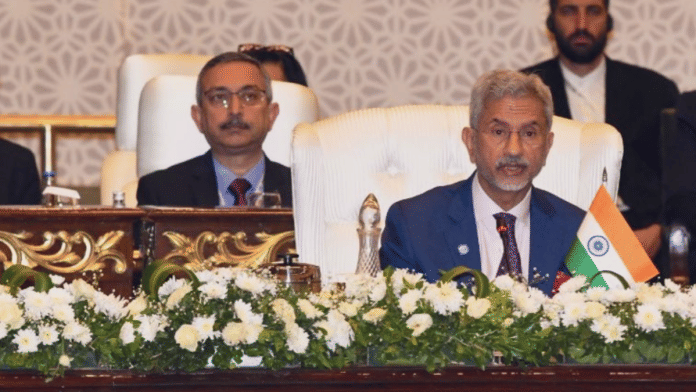

Minister of External Affairs S Jaishankar, who attended the two-day summit in place of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, brought his signature swagger to the proceedings. He made it clear that India’s participation in the Council of Heads of Government meeting was to fulfil its obligations to the SCO and not to interact with the host country. No bilateral meetings occurred between the two sides at the event, which was overshadowed by the unusually escalating tensions between India and Canada.

Even as journalists scrutinised interactions, statements, body language and strategic commentary, India’s participation remained overall restrained, with sharp rebuttals to any attempts to thaw tensions with Pakistan.

Eurasia and South Asia

The SCO is a political, economic, and security organisation founded by China and Russia in 2001. Initially a Eurasian alliance, it expanded in 2017 when India and Pakistan joined. Iran became a member in 2023, followed by Belarus in 2024. The organisation also includes several observer states and dialogue partners. With both China and India as members, SCO is the world’s largest regional alliance in terms of population – a factor that contributes significantly to its economic influence.

The SCO was established in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, which explains why counterterrorism is its core focus. However, given Pakistan’s history of sheltering anti-India elements, the SCO’s counterterrorism framework offers limited value for New Delhi, which I will elaborate on later in the article.

For Russia and China, the SCO remains central to their strategic efforts to advance an alternative global order.

Also read:

Multi-alignment and discontent

India’s engagement with the SCO is a key reflection of its multi-alignment and reinforces its commitment to regional cooperation. It is crucial to prevent regional organisations such as the SCO from succumbing to China’s dominance. Especially when the world is grappling with complex dependencies on Beijing and there’s a growing effort to counter the nation’s unilateral moves and disregard for international law.

While India may not reap significant direct benefits from the SCO—given the sanctions on Iran and Russia and the limitations on trade with both—it must continue its participation to ensure the region isn’t dominated by China. It’s important to remember that Beijing’s involvement with the SCO aligns with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which most SCO members, except New Delhi, have endorsed.

Russia’s capacity to balance China has weakened due to the Ukraine war, increasing its reliance on Beijing. Simultaneously, events in the Middle East have drawn Iran even closer to the authoritarian axis of Russia, China, and North Korea. Thus, for pragmatic reasons, India must continue its engagement with the SCO.

The SCO risks becoming an anti-Western bloc without India – an outcome New Delhi can ill afford. The country aims to leverage its multi-aligned stance to benefit from both sides of the global divide while assuring emerging economies of its commitment to collaborative regionalism in an increasingly polarised era.

Also read: To let China invest in India or not—an old economic problem has struck policymakers again

Lack of commonalities

The fundamental issue with the SCO is the absence of a unified economic, strategic, or regional vision. India does not align with the China-Russia-Iran trio’s efforts to undermine the existing global order. Over the past few years, India has significantly diversified its trade, investment, defence, and technological partnerships with the West, a trend likely to continue despite simultaneous engagement with partners such as Russia and Iran.

At its core, the SCO lacks a common or preferential free trade area or mechanism. While China is a major trading partner for many SCO members, its export-driven and highly imbalanced trade has created dangerous dependencies rather than fostering equitable and sustainable trade patterns. India’s trade with Russia, primarily driven by oil imports, has surged, but it has also resulted in a ballooning trade deficit that both countries are struggling to address.

Trade with Iran has become challenging due to the heavy sanctions on Tehran. However, Chabahar Port, located in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province, serves as a crucial economic gateway for India. Easily accessible from Gujarat’s Kandla Port, Chabahar is strategically positioned near the Strait of Hormuz, a vital maritime trade route. Through Chabahar, India can access Afghanistan and the landlocked countries of Central Asia.

Recently, India linked Chabahar with the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), though the corridor is yet to become fully operational. Despite sound strategic planning, there are practical hurdles, such as the heavy sanctions on Russia and Iran and the ongoing war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, Chabahar provides India with a strategic vantage point to monitor China’s activities in the Persian Gulf. Additionally, India has strengthened its presence in Haifa, Israel, through investments by the Adani Group (among others), aiming to use the port as a pivot for the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). However, this initiative remains stalled amid the region’s instability.

A fully operational Chabahar would also allow India to bypass Pakistan for trade with Afghanistan. Trade between India and Pakistan has effectively ceased, with exports declining further in 2024.

While Chabahar holds strategic value, it does little to compensate for the lack of a cohesive economic vision among SCO members. Without it, the organisational framework remains limited in its potential for fostering deep, sustainable economic ties.

Another common misconception about the SCO is that it is often mistakenly referred to as “Asian NATO”, a counter to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in Asia. Conflating the SCO, which includes India’s arch-rivals China and Pakistan, with NATO’s collective security framework is incorrect.

Article 5 of NATO, an old-school security alliance, provides ironclad collective defence for its members. This principle of collective defence has never been violated. Central and Eastern European states view their NATO membership as the only credible guarantee of their territorial integrity, which explains Ukraine’s relentless and troubled pursuit of membership. It also sheds light on why historically neutral countries such as Sweden and Finland joined NATO after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

The SCO does not have a remotely similar security arrangement. It does not offer security guarantees where an attack on one is considered an attack on all. Instead, the SCO has a specific focus on counterterrorism through its permanent agency, the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS), based in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. RATS is one of two permanent SCO agencies. The other one is the SCO Secretariat in Beijing, the organisation’s primary executive body that’s responsible for implementing crucial decisions, among other things.

RATS has played a key role in counterterrorism operations, though its successes have primarily benefited China and Central Asian countries. Between 2011 to 2015 alone, RATS reportedly disrupted 20 planned terrorist attacks, prevented over 600 terrorist crimes, dismantled over 400 terrorist training camps, and made thousands of arrests.

However, for India, these efforts offer little respite. Pakistan, backed by China, remains a significant exporter of cross-border terrorism into India. As a result, the SCO’s counterterrorism framework does not address New Delhi’s core security concerns.

SCO’s regional framework provides little benefit but remains a good platform for India to complement its efforts around specific projects such as the INSCT and Chabahar. The country stands to gain from engagement with SCO, especially as geopolitical churning deepens. It must continue to do so, though with strategic realism.

The writer is an Associate Fellow, Europe and Eurasia Center, at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

The author has missed out an important aspect.

India’s leadership role in Global South has weakened during Modi era as in most countries of Global South India is perceived as closer to US and its NATO / EU allies. Historically India was was perceived as more friendlier country than China in Central Asia. Lately this is changing. China has completely replaced India in this region. Indi needs to play more dynamic role in SCO if it wants to be an important player in the region. Already BRICS and SCO are more popular in Global South and even European Countries are keen to join BRICS. If India wants to retain its leadership role in BRICS and SCO, has to show dynamism before it is too late.