Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the central government’s budget for India for the upcoming financial year 2022-23 on Tuesday. The total projected expenditure for 2022-23 is Rs 39.45 lakh crore. Of this, about 3.1 per cent or Rs 1.24 lakh crore is the share of the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare. Out of this share, three schemes – PM Kisan, Rs 68,000 crore; interest subvention on short term credit, Rs 19,500 crore; and crop insurance, Rs 15,500 crore – take away Rs 1,03,000 crore. The two other major schemes are Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) and Krishi Unnati Yojana (KUY).

In this article, we list the changes in budgetary allocations of key schemes/programmes that are likely to affect the Indian agriculture sector.

Restoration of important schemes

Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY): This 2007-08 central government scheme is a relatively flexible one that gives autonomy to state governments to prioritise schemes within the larger allocation. Depending on regional and local priorities, states could decide interventions under this programme. Over the years, the scheme was being tapered down. This year, however, its allocation has been increased by 422 per cent: from Rs 2,000 crore (RE2021-22) to Rs 10,433 crore. This reinforces the Centre’s drive to give some more autonomy to states and allow them to take forward the baton of agricultural reforms and growth.

Krishi Unnati Yojana (KUY): With an allocation of Rs 7,183 crores, KUY makes its refreshed debut in India’s budget statements. First introduced in 2016-17 as a cluster of 10 schemes and a budgetary allocation of Rs 7,580 crore, Krishi Unnati Yojana has been reintroduced in 2022, with a different set of 10 schemes and a budgetary allocation of Rs 7,183 crore. This time it combines under its ambit some of the older ‘green revolution’ schemes. About 26 per cent of these funds are for the development of the horticulture sector. Oilseeds and edible oil prices have been on fire last year, particularly owing to the high global prices. So, to encourage their domestic production and processing, about 21 per cent of KUY funds are allocated to palm, edible oil and oilseeds.

Also read: Most Indian farmers faced erosion of their real incomes since 2012-13 but survey can’t tell

Tapering in others

Paramparagat Krishi and Organic Farming: In the reshuffle of schemes under KUY, one interesting fact has come to notice. Organic farming, zero budget farming, and paramparagat kheti (traditional farming) seem to have lost their sheen. Introduced in 2019, zero budget farming was positioned as one of the key drivers of farmer income growth. Concurrently, budgetary allocations for traditional and organic farming were seen rising in the successive budgets. This year, however, except for the Northeast region where allocation is made for developing the organic value chain, ‘Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana’ and ‘National Project on Organic Farming’ programmes do not find a mention. Probably, RKVY may take care of this. But given the prime focus for ‘chemical free natural farming’ in the budget speech, one did expect a specific scheme with a substantial outlay.

Agri Infrastructure Fund (AIF): As part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat package, PM Narendra Modi introduced the ‘Rs 1 lakh crore Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF)’ for farm-gate infrastructure for farmers. In 2021-22, GoI budgeted about Rs 900 crore for it, but only Rs 200 crore has been used. In 2022-23, GoI budgets Rs 500 crore, much lower than its target for the last year. Does it mean that the Centre’s AIF has not picked pace as expected? Infrastructure is one of the key pillars of this budget. Is there a rethink on the guidelines for AIF?

Also read: India can’t afford a hurried resolution on MSP demand. It can cause chaos, long-term damage

Govt indicates change in focus

Stubble burning sparked a health concern, particularly for people living in the northern areas of Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab. Every year, the GoI has been budgeting for promoting mechanisation for ‘in-situ management of crop residue’. This year, the allocation under this head is nil. From Sitharaman’s speech, it appears that this biomass will be used towards thermal power generation, although no allocation in that regard is clear in the budget.

PM Aasha: Last year, prices of both oilseeds (mustard, soybean) and pulses (tur, lentil, gram) were high. When market prices are above MSP, farmers offer less or no produce to GoI for procurement under MSP. Not surprisingly, the Centre’s expenditure under the PM Aasha scheme (GoI’s scheme of ensuring MSP to pulses, oilseeds and copra farmers) was low, only about Rs 1 crore (RE 2021-22) out of the budgeted Rs 400 crore. What is interesting is that the finance minister has budgeted only Rs 1 crore under PM Aasha this year. This may mean two things, inter alia, (i) GoI is assuming that prices will continue to remain higher than MSP this year too and thus does not anticipate momentum in the MSP procurement operations, or (ii) it could mean that GoI is winding up PM Aasha too, unless this is being merged with food subsidy.

NREGA: As per the recently released data on farmer incomes by the National Statistical Office (NSO), an average farmer household earned only about 37 percent of their household incomes from cultivation activities. About 40 per cent came in the form of wages and salaries, of which National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) was a focal contributor, at least for the small and marginal farmers (with landholding sizes below two hectares). During the pandemic-induced lockdown, when millions of migrant labourers returned to their villages, NREGA acted as a shock absorber. A 25 per cent reduction in NREGA budget this year is likely to hurt an economy recovering in a k-shape. The economy is still grappling with high unemployment with lower labour force participation rates. Shrinking expenditures under NREGA at this time may hurt the distressed.

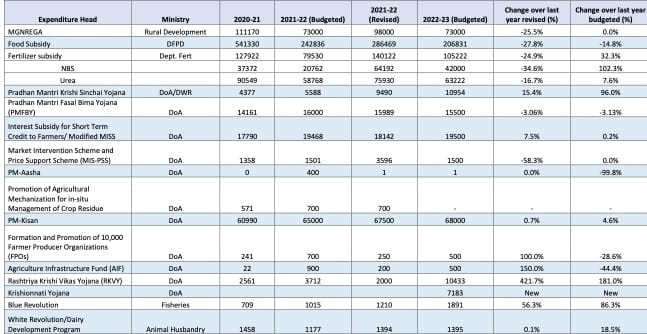

Apart from these, there are welcome increases in the allocations for animal husbandry and fisheries reflecting their importance in the food basket and their growth performance. Data on key programmes and scheme budgetary expenditures is summarised in the table below.

Table: Budgetary allocations under key programmes/schemes

Overall, it appears that Budget 2022-23 is indicating the changes in GoI’s focus. No more are there talks about doubling farmers’ income or organic farming in the way it was done until last year. Some crucial schemes have been stopped or subsumed and many older ones have been renewed. We truly wish the budget lays foundation for the ‘Amrit Kaal’, a word coined by the finance minister in her speech that refers to the 25-year-long lead up to year 2047 when India will celebrate its 100 years of Independence. In the digitised, infrastructure-led economic growth, do not let farmers and the rural landless feel left out.

Shweta Saini is Senior Visiting Fellow at ICRIER. She tweets @shwetasaini22. T Nanda Kumar is former Union secretary, Food and Agriculture. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)