As reports emerge of the Narendra Modi government agreeing to all demands of the protesting farmers, including guarantees for MSP, India should ask questions on the possible support pricing regime and the direct fiscal impact it can have.

Questions of equity and sustainability are yet to be considered — which class(es) of farmers have surpluses to sell? Which regions have better infrastructure to procure? What happens to rainfed area farmers who do not get input subsidies and have no access to procurement systems? These can be addressed later.

But first, we need to get conceptual clarity on the demand. Is the demand being made for a ‘mandatory’ MSP or a legally guaranteed MSP? There is a difference.

A mandatory MSP means that it will be illegal for anyone to buy any notified commodity at below MSP anywhere in India. If MSP is made mandatory, the government (read inspectors) will have to ensure that every single transaction confirms this legal requirement. Any violation will have to be punished. Traders might find it safer to stay away from the market and wait for the government to offload stocks in the market. Government then becomes the sole trader? A sure recipe for disaster.

The present demand seems to be for a ‘legal’ guarantee (trust-based system vs a rights-based one) that the government (states and Union) will purchase all the goods offered at MSP. This would be more like an expanded pan-India procurement operation, similar to the one in Punjab plus a few other states. Farmers demand (clearly there is lack of trust and hence a rights-based system) that this scheme be embedded in a law like the National Food Security Act (NFSA), which ensures the ‘right to food’. A cash payment in lieu of grains is provided as a ‘fall back’ provision under NFSA as well. Therefore, a ‘guaranteed’ MSP can be a procurement scheme, a price deficiency payment option, or a combination of the two. If this is the way forward, what would be the implications?

Also read: What did the farmers’ movement achieve? The original andolanjeevi, Gandhi, has an answer

Cost implications

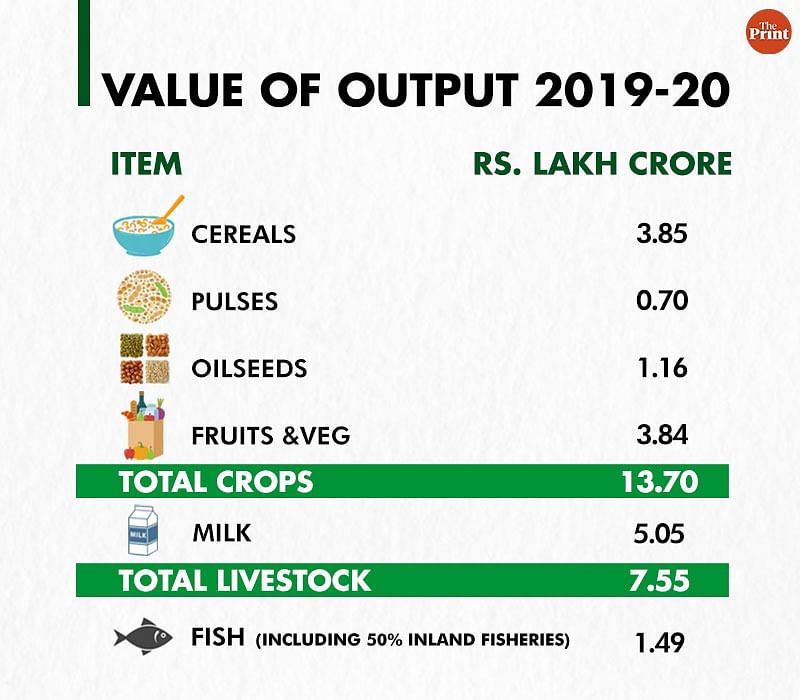

Is the demand for legal guarantee restricted to the 23 commodities already covered under MSP? If so, what are the reasons to exclude farmers who grow crops outside of MSP regime? There is no certainty that non-MSP farmers will not demand MSP. To understand the possible implications, let us take a look at the value of output in agriculture.

The value of the 23 crops presently covered under MSP works out to about Rs 7 lakh crore. Leaving aside administrative and logistics considerations, let us look at the cost implications of such a proposal.

Kiran Vissa and Yogendra Yadav have argued that it will cost the government only an additional Rs 47,764 crore (2017-18 data) if a legally guaranteed MSP is provided. This calculation, among other things, does not take into account the current total food subsidy of about Rs 240,000 crore, which is mostly consumer subsidy.

If the proposition for a legal guarantee is taken forward, the government will have to continue with the current procurement policy, add a price deficiency payment guarantee and manage a hybrid system. In such a scenario, the government will continue to incur a food subsidy of Rs 240,000 crore (to go up every year since MSP goes up and issue prices remain constant) and add about Rs 50,000 crore-plus every year. Since a lot will depend on market conditions, the government will have to look at a bill of Rs 300,000 crore or more on this account.

Also read: Low enrolment & farmers ‘unpaid’ in Punjab’s ‘Pani Bachao, Paise Kamao’ scheme, but power saved

The bottlenecks

Cereals (other than wheat and rice ), pulses and edible oils are procured, and sold in selective auctions under a broad “open market sale scheme”, mostly at lower prices. If we go by the history of open market sales of wheat and rice, the net loss to the government would be more or less equal to what the FCI incurs, about 40-45 per cent of MSP. The subsidy burden of any procurement operation, therefore, will not be less than 30 per cent of the value, considering lower distribution costs. Estimating the cost of a legally guaranteed MSP even for the 22 crops (leaving out sugarcane) is fraught with risks. Market prices and quantities could vary significantly. But going by the wheat-rice example, government may have to consider the following:

- MSP, backed by some form of government guarantee, with ‘limited’ physical purchase and price deficiency payments could be the option. An open-ended procurement linked to PDS and open-market sales of surplus will be disproportionately costly and difficult to implement. Is it time to delink MSP from procurement for PDS?

- The government needs good reasons to convince farmers growing non-MSP crops and explain to them why MSP is being restricted to 23 crops. They might choose to shift to MSP crops, creating another set of issues on the ‘Tomato, Onion, Potato’, TOP

- Considering the revenue receipts of the Union government are estimated at Rs 17.88 lakh crore ( 21-22 BE), can the government increase the food subsidy from Rs 2,40,000 crore to Rs 300,000 crore plus? This is in addition to PM KISAN, fertiliser and other subsidies.

- Can the government reduce its coverage under NFSA as, given the latest multi-dimensional poverty data, case for reducing the coverage to 40 per cent becomes stronger and revise the issue prices under PDS to partially offset the subsidy burden?

- Do equity and sustainability considerations demand that the government shift to a PM KISAN type income support system across the board to take care of the fruit and vegetable, dairy and rainfed area farmers, considering their production and price risks?

- Shouldn’t state governments be actively involved, given more flexibility and take primary responsibility for improving farmers’ income?

A legal guarantee for MSP is not a simple issue. It needs wide-ranging consultations. A hurried resolution is likely to result in chaos and long term damage.

T Nanda Kumar is former Union secretary, Food and Agriculture. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)