Last week, the Karnataka Legislative Assembly caused a storm with new labour proposals, since put on hold: reservation for Kannadigas in the private sector and a 14-hour workday. Much has been said about the economic and political problems these are meant to address and will cause, particularly in cosmopolitan Bengaluru.

But that barely scratches the surface. The fact is that despite being Karnataka’s greatest metropolis, Bengaluru’s history does not belong to Karnataka alone. It has been shaped by centuries of migration, trade, and exchange. The history of Bengaluru encapsulates the history of all of south India: Kannadigas, Telugus, Tamils, and more.

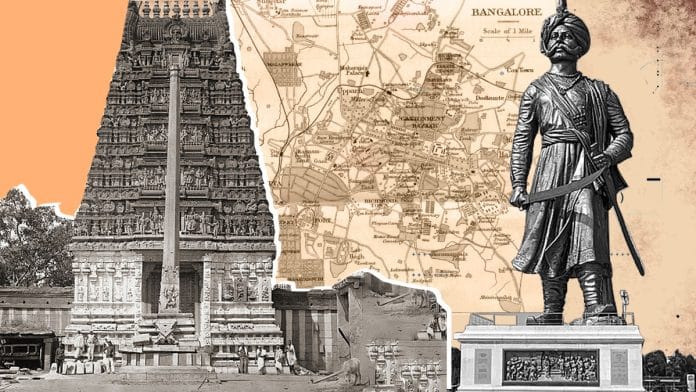

A crossroads of trade

The Bengaluru region is one of the longest continually-occupied zones in the entire Indian subcontinent, influenced by innovations and changes across South India. This was driven by the region’s geography: a cool, settled highland between two coasts, with rich mineral deposits of its own. Traders moved between the Malabar and Coromandel coasts via South Karnataka, bringing ideas and goods to local chiefdoms even before the city was founded. This is evident in the city’s archaeology. In 1891, workers at Yeshwantpur—today the site of a massive railway station—found a pot containing 163 Roman coins, dating from 23 BCE to 51 CE. Around 2004, ruins of a Buddhist monastery, active from the 2nd–7th centuries CE, were found in Rajaghatta, near Bengaluru’s international airport today.

The decline of this monastery corresponded with the beginning of the early medieval period. Warlike new states emerged across Southern India, using Sanskrit as a language of power and revering Shiva as a royal god. Some states were based around Bengaluru, and through their remains, we can see a gradual increase in the region’s population and its increasing “international” connections within South Asia.

The name “Bengaluru” first appears in inscriptions commemorating raids between local chiefs. Manne, just north of the future Bengaluru city, was ruled by the Western Ganga kingdom, frequently at war with the Rashtrakuta empire of the central Deccan. Rashtrakuta attacks killed many in the Bengaluru region, including a certain Kittayya, later declared “Bengaluru’s first known citizen.” As part of their war with the Rashtrakutas, the Gangas married one of their princesses to an Odia king; she ruled there briefly as a revered regent.

In the mid-9th century, the Rashtrakutas and Gangas formed an alliance. The Rashtrakuta poet-emperor Amoghavarsha I (r. 814–878 CE) declared that “the Kannada country extends from the river Kaveri to the Godavari,” though this was somewhat of an exaggeration, ignoring South India’s growing multilingualism. Many Kannada poets, such as Pampa, author of the first Kannada Mahabharata, came from coastal Andhra—where Telugu was widely spoken. Interestingly, in the 9th century, the Rashtrakutas considered north Karnataka the heartland of Kannada. Thanks to Bengaluru, South Karnataka would soon challenge this.

Also read: How Karnataka’s medieval Lingayats challenged caste, oppression of women & toppled empires

Multilingual history

A dramatic cultural change is visible in the Bengaluru region from the late 10th–early 11th centuries, almost exactly 1,000 years ago. The Rashtrakuta and Ganga kingdoms collapsed, and into the vacuum arrived the Chola empire. Following the Kaveri River east, they brought Tamil merchants and peasant-warriors to settle in the Bengaluru region. According to data from the Inscription Stones of Bengaluru project, temple inscriptions in the region shifted from mostly Kannada to mostly Tamil.

This was not because locals were wiped out. Instead, many local chiefs adopted Tamil titles and used Tamil in their inscriptions, some of which can be seen in the temples of Chokkanatha at Domlur and Someshwara at Madiwala. By the 13th century, the flow of immigrants was reversed. The Hoysala kingdom of South Karnataka conquered parts of the lower Kaveri floodplain, and Kannada-speaking merchants and generals began to appear in Tamil temple inscriptions.

The movement of people between the upper Kaveri (in present-day South Karnataka) and the lower Kaveri (present-day Tamil Nadu) is under-appreciated. It became one of South India’s defining dynamics in the late medieval period, particularly after Bengaluru was finally founded as a fortified market town by the local chief Kempegowda in the 16th century.

Structures dating to this period, such as the towers of the Bhoga Nandishwara and Ulsoor Someshwara temples, were built in a local variation of Vijayanagara imperial style. Vijayanagara itself was a Karnataka-based empire dominated by a Telugu-speaking warrior class, whose architecture was based on Tamil models with Persianate ideas. As such, Tamil and Telugu speakers were present in the Bengaluru region before and after the city’s founding. Within the next hundred years, Marathi speakers also joined Bengaluru when it was briefly conquered by members of the Bhonsle family—the father, brother, and son of Shivaji.

Also read: South India challenges the notions of medieval Islam—lessons from Deccan history

Whose Bengaluru?

This dizzying procession of dynasties and states only ended in the 18th century, after the British defeated the Mysore king Tipu Sultan. The city was then “partitioned” between the British cantonment and the old market area, ruled by Mysore’s Wodeyar dynasty. The British were accompanied by their Indian troops, including the Tamil-speaking Madras Sappers. They settled at Ulsoor, serviced by a thriving Tamil, Telugu, and Marathi merchant population. As Bengaluru took on its modern shape, it continued to be linguistically diverse. Meera Iyer, convenor of INTACH Bengaluru, writes in Discovering Bengaluru that an 1896 petition included signatures in Kannada, Telugu, Hindi, English, and Urdu.

All of this brings up the question: whose Bengaluru is it anyway? When the city was founded, would its residents have even recognised modern concepts of linguistic states and identities, when many of them were proficient in more than one language? And even beyond the city, much of South Karnataka has a long history of international connectivity. This enabled Bengaluru to emerge as the major economic centre of Karnataka, but without long-term planning, it ended up creating an unequal, Bengaluru-focused picture of the state’s development.

There is no question that inequality and economic distress, both within Bengaluru and in North Karnataka, need urgent redressal. But reservations solely for Kannadigas is an ahistorical solution. The Bengaluru region’s greatest strength is its ability to accommodate many vibrant cultures and peoples, to make them its own, and to prosper as a result.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)

Flawed arguments. The most recent migration to Bangaluru differs from the earlier ones as instead of migrants adapting and respecting the culture of their hosts, they want to impose their culture and values on the hosts. Also, they have not come to settle and treat Bangaluru as their home. They just want to exploit it and move on

ALL i can see in this article is the AGENDA of an outsider claiming Bengaluru. He narrated this article in such a way that people who came to Bengaluru for work and settled here are claiming Bengaluru belongs to them. such an anti- Kannadiga and BIASED article. This article proves why Kannadigas need to stand up now otherwise this outsiders will claim every part of the Karnataka.

OUTSIDERS : PEOPLE WHO ARE NOT NATIVE TO THE PLACE (this is for those who will come and blabber that I’M Indian i have right to stay anywhere in the country. yes i know this rights. but that doesn’t make you guys native people)…

You are one idiot, Our past kingdom tells our history. Your entire Andhra ruled by Krishnadevaraya. I want to ask Print how can you tell outsider from Andhra to make article on Karnataka

Agenda peddler. Typical migrant parasitic behaviour. Filled with half truths, lies and absolute horse shit.

It belongs to kannadigas, period, the settlement was done in 1956 with states re organisation act , don’t peddle non sense , every state has right to protect its citizens,

Where were you where when other neighbour stated did the same. 1000 years back every region was different and languages were different. if we go back 2000 years back also and so on…..