The most imposing British colonial buildings in India—such as the Asiatic Society of Mumbai or the recently refurbished Hyderabad Residency—have a form that isn’t British at all. They look more similar to buildings from imperial Rome, with triangular roofs and towering columns. Architectural historians call this style “neoclassical”—a marker of how the British imagined an ancient empire, a conscious attempt to position themselves as Rome’s heirs.

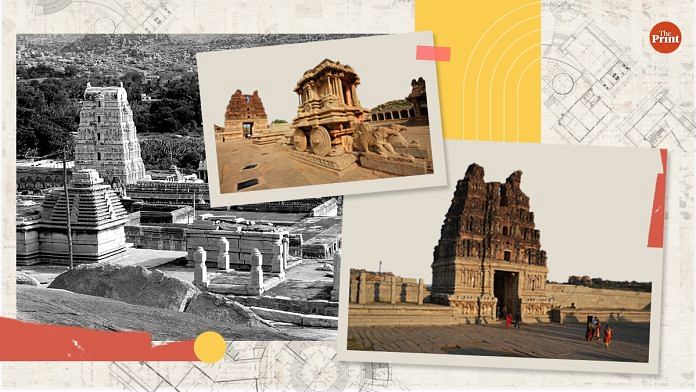

What might surprise you is that Indian empires did the exact same thing. Hampi/Vijayanagara, whose ruins have inspired many a tourist, photographer, and historian, was truly an Indian Renaissance State. It freely adapted elements from the collapsed Chola and Chalukya empires, creating a revolutionary new body of South Indian architecture.

The rise of transregional empires

During the 15th century CE, two remarkable states emerged on the Deccan Plateau: Vijayanagara and the Bahmani Sultanate, on either side of the Tungabhadra River. Given their location in the Deccan, these states were multiethnic and multicultural from the outset.

You see, for centuries prior, the Deccan had been a vibrant crossroads, comprising three linguistic zones: Marathi, Telugu, and Kannada. For much of the early medieval period (600-1100 CE), Kannada-speaking dynasties, like the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas, dominated the plateau through complex systems of vassalage and marriage alliances. Such decentralised systems had been the only way to control the arid, warlike, and relatively non-urban region. But by the 12th century, they were no longer tenable. Consequently, each linguistic zone developed its own regional dynastic political structure: the Seuna Yadavas in the Marathi zone, the Kakatiyas in the Telugu zone, and the Hoysalas in the Kannada zone.

Yet, even these states proved ultimately fragile. The Delhi Sultanate eliminated their political centres in the 14th century, and by the 15th, Vijayanagara and the Bahmanis rose to fill the political vacuum. Vijayanagara, expanding across the South Indian peninsula and reaching the Coromandel Coast, capitalised on the allegiance of migrating Telugu and Kannada peasant-warriors. As we’ve seen in a previous edition of Thinking Medieval, imperial expansion was not exactly a pleasant process. Though texts like the Madhuravijayam claim that Vijayanagara “rescued” Tamil Nadu, assimilating the vibrant urban and social systems of the region into Deccan domination took nearly a century. The picture was equally messy in Bahmani territories, a topic we will explore in a future column.

To foster acceptance of their rule in Tamil Nadu, Vijayanagara strategically selected and patronised temple centres that commanded local loyalties. The great Nataraja temple at Chidambaram was one; the Ranganatha Swamy temple at Srirangam was another. In the 16th century, Krishna Raya of Tulu descent, who became the most powerful emperor of Vijayanagara, wrote the Amuktamalyada, a Telugu courtly text about Andal—a Tamil Vaishnavite saint believed to be Ranganatha’s consort. Raya cited a dream in which an Andhra form of the god asked him to do this, while he was on campaign against the Gajapatis of Odisha. While devotion undoubtedly played a role, it’s also possible to see in the Amuktamalyada a literary culmination of transregional politics: a Tulu ruler writing for a ruling coalition of Telugu warriors and Tamil priests.

Also read: Don’t romanticise Vijayanagara as the ‘last Hindu empire’—it has a side you don’t know about

Architecture and transregionalism

Last week, I travelled to the ruins of Vijayanagara with members and patrons of the Deccan Heritage Foundation. The trip was led by Dr George Michell, a distinguished architectural historian and co-lead of the Vijayanagara Research Project. Dr Michell pointed out that the earliest temples at Vijayanagara were very much in the early medieval Deccan idiom. In the foreground below, you can see a complex of funerary temples built by Vijayanagara’s founding dynasty in the 14th century (ignore the more recent temple tower in the background). Notice how the temple’s main hall features a porch with a sloping roof and parapet walls flanking the entrance.

For comparison, here’s the 11th century Mallikarjuna temple at Sudi, partially commissioned by a Chalukya queen, which has a similar main hall. You might also note that the proportions of the vimana—the small tower over the sanctum—are quite similar. The Vijayanagara vimana, which looks (in Dr Michell’s words) a bit like a layer cake, is essentially a simplification of the structure of the older Chalukya vimana. Its walls are undecorated, except for a band of geometric reliefs.

So far, so good. Both Vijayanagara and the Chalukyas were Deccan states, so this architectural similarity is exactly what we expect. But let’s examine a 15th-century temple: the Hazara Rama temple, an expression of Vijayanagara’s imperial ideology, built after its conquest of Tamil Nadu.

The design of the wall is completely different here: deep niches (with sculptures that are now lost), framed by split columns. Between these niches, half-columns emerge from sculpted vases. All these elements are alien to the Deccan—but they are native to Tamil temples. For comparison, consider the 12th century Airavatesvara temple at Darasuram, where the treatment of walls is similar but more elaborate. Deep niches, still containing sculptures, are framed by split columns, and interspersed with half-columns emerging from vases.

But that’s not all. Here’s a late 15th to early 16th-century Vijayanagara temple, dedicated by Krishna Raya’s Tuluva dynasty to the god Vitthala. You’ll instantly notice that its conception of the hall is completely different from the first Vijayanagara temple we saw. Gone are the parapet walls. The vertical proportions are magnified. The pillars comprise multiple smaller elements: riders on top of fantastical creatures positioned at auspicious points (foreground). A secondary row of pillars (background) is now decorated with miniature temples.

Again, consider a comparison with the Airavatesvara temple. Observe the fantastical beasts on the outermost columns, and then the ones closest to us. The logic remains consistent: outer columns offer protection and therefore contain frightful creatures, while inner columns have sacred figures. Vijayanagara has a much more evolved expression of this logic.

What we can see in these stone structures, then, is a radical transformation of the Renaissance-era South Indian temple, occurring at the same time that Vijayanagara emperors were making literary and religious attempts to integrate conquered cultures. I asked Dr Michell about the reasons behind this architectural revolution. He pointed out that we can only guess at the motives of the Vijayanagara emperors. They left us no diaries. Perhaps they did not find the older Deccan architectural idiom sufficiently imposing. Perhaps they found plenty of out-of-work Tamil sculptors willing to innovate to fulfil their new patrons’ creative vision.

Or, perhaps this new, transregional empire needed a new, transregional architectural idiom: one that outdid the Cholas and the Chalukyas, one that met the challenges of a transforming world with a confident reimagining of South India’s long imperial history. Temple architecture is not eternal or unchanging; it has its own logic and language, serving as a historical footprint to the ever-changing people who made them.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)