Emperor Ashoka, writing in the middle of the third century BCE, spoke of his diplomatic initiatives, which included foreign aid in the form of medical materiel and know-how:

Everywhere — in the territory of the Beloved of Gods, King Piyadasi, as well as in those at the frontiers, namely, Codas, Pandyas, Satiyaputras, Keralaputras, Tamraparnis, the Greek king named Antiochus, and other kings who are that Antiochus’s neighbours — everywhere the Beloved of Gods, King Piyadasi, has established two kinds of medical services: medical services for humans and medical services for domestic animals. (Rock Edict II)

Ashoka was evidently proud of the quality of Indian doctors, medicines, and medical technologies, including veterinary medicine. But why did Ashoka single out medicine as an area where he could provide aid and exert influence in foreign countries? Did these countries lack medical knowledge and materiel?

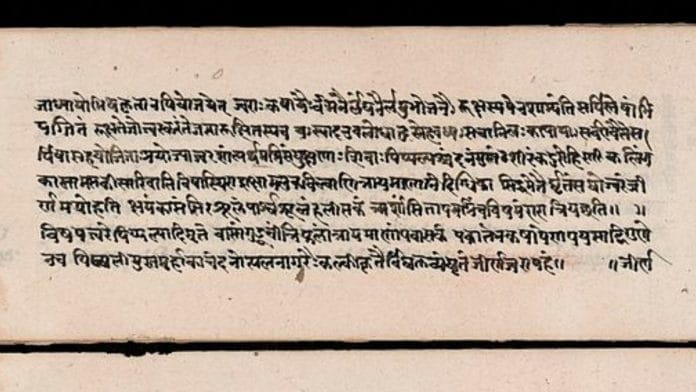

It is instructive in this regard to look at the early history of Indian medicine, which later developed into the system of Ayurveda. Recent scholarship has thrown some light on that early history and its close association with the ascetic traditions, particularly Buddhism, in the region of Magadha, Ashoka’s birthplace.

‘Medical diplomacy’

The development of an empirical medical science and practice within Buddhism and in the heartland of the Maurya Empire may have been a source of pride for Ashoka. Possibly, he received information about the lack of such practical medical expertise, both in the outlying regions of his empire and in neighbouring countries. These regions may have been receptive to new forms of medicine and medical technology. If so, we can understand why Ashoka may have engaged in medical diplomacy.

Kauṭilya’s Arthashastra also attests to a highly developed medical profession for treating both humans and livestock, especially horses and elephants who were integral parts of the ancient Indian armies. Physicians and experts in poisons were expected to be near the king at all times (1.21.9–10). The king’s personal physician was expected to take medicine for the king from the pharmacy, test its purity by tasting it himself, and have it tasted by the cook and the pounder, before presenting it to the king. The personal physician of the king was clearly an important position with an elevated status within the state bureaucracy. Kautilya gives no hint that medical practitioners were affected by any social or legal disability.

Nevertheless, it has long been noted that ancient India exhibited a kind of schizophrenia with respect to the medical profession. On the one hand, we have learned treatises on medicine and surgery produced in the first half of the first millennium of the common era, treatises that point to a long and distinguished tradition of medical learning known as Ayurveda. On the other hand, we have a long line of Dharmashastras, the major textual tradition dealing with religious, civil, and criminal law, and providing guidance to living a virtuous life that disparages the medical profession and prohibits social and religious interaction with medical practitioners. They are saddled with numerous social and religious disabilities. Manu (4.220), for example, prohibits eating the food of medical professionals or inviting them to any religious ritual:

The food of a medic is pus; the food of a lascivious woman is semen; the food of a usurer is excrement; and the food of an arms merchant is filth.

The Mahābhārata (5.35.37) lists medics among people who should not be called as witnesses in a court of law.

The texts of Ayurveda too appear to recognise that their profession had an image problem. If you were walking down the main street of a town or city in ancient India, you would encounter all sorts of people trying to sell you a variety of goods from gold to garlands. That was unsurprising then, as it is now.

But there would be one thing surprising: you would notice a few strange fellows dressed gaudily and carrying books. They try to pick up clients, people who may have sick children, or relatives at home. They are the ancient medical equivalent of the modern-day ambulance chasers. Here is how Caraka (Sutrasthana, 29.8–13), the author of the oldest extant medical treatise, portrays these medical hucksters trying to peddle their cures:

Cloaking themselves with the garb of physicians and becoming thorns to the people, these fakes wander across countries. This is how one can recognize them: being extremely pompous in the attire of a doctor, they stroll down the market streets because of their yearning to obtain work; and when they hear that someone is sick, they rush toward him.

Also read: Kautilya’s ‘Arthashastra’, Manu’s laws—Ancient India had rich literature on jurisprudence

‘Vaidya’

In the Ayurvedic texts, we have evidence that the leaders of the medical profession were trying to clean up their image and get rid of charlatans among them. As part of that initiative, they invented a new term – vaidya – to designate a physician. This term, with its etymological connection to the Veda, is never used in the early literature, including the Arthashastra and the Dharmashastras. We cannot be far wrong in dating the widespread use of ‘vaidya’ for a medical practitioner to the beginning of the common era. The use of ‘vaidya’ is associated with the attempt within the emerging medical profession of Ayurveda to professionalise medical education and to elevate the status of the doctor. Caraka (Sutrasthana 9.22-23) observes:

Knowledge, intellect, practical observation, continued practice, success (in treatment), and dependence (on an experienced preceptor)—even one of these is sufficient to justify the use of the title vaidya. But someone who possesses all these excellent qualities beginning with knowledge, giving comfort to all living beings, deserves the title vaidya properly so-called.

The elaborate initiation into medical education, which is deliberately modelled after the Vedic rite of initiation (upanayana), further strengthens the thesis that organised medical education sought to elevate the status of a physician. Both these reasons—knowledge and initiation—for the new status of a vaidya are presented by Caraka in a significant passage (Cikitsasthāna, 1.4.52-53):

At the complete acquisition of knowledge (or, conclusion of study), the second birth of a physician is said to take place, for he obtains the title of doctor; one is not a doctor through the earlier birth.

At the complete acquisition of knowledge, the Brahman’s or seer’s spirit enters him firmly because of his knowledge; therefore, the doctor is declared to be a twice-born (dvija).

What these two verses clearly do is anchor the exalted status of a physician on the fact that he is a learned doctor (vaidya), and it is this status that confers on him the second birth and the title of ‘twice-born’, that is, a true Brahmin. The vaidya is also given the title of acarya, which means teacher. But unlike other teachers, he is called a pranacarya, a teacher with respect to life itself. As such, he is to be respected; one should never offend him (Caraka, Cikitsāsthāna, 1.54).

The vaidya and pranacarya are clearly distinct from the ‘charlatans’ one sees roaming the streets.

Quite the opposite of this are the companions of diseases and destroyers of lifebreaths. Cloaking themselves in the garb of physicians and becoming thorns to the people, they wander across countries because of the negligence of kings, having the characteristics of a fake. (Caraka, Sūtrasthāna, 29.8-13)

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)