He said, she said.

To 2021, some phrases like the one above seem almost calculated to inflict wilful blindness upon culture. Our morning memes and aphorisms are full of shortcuts to mindfulness, heuristics that gain credence as we pay them forward to our friends. That easy mindfulness can slowly dull into the mental blankness of acceptance is the everyday tragedy of life as it transpires.

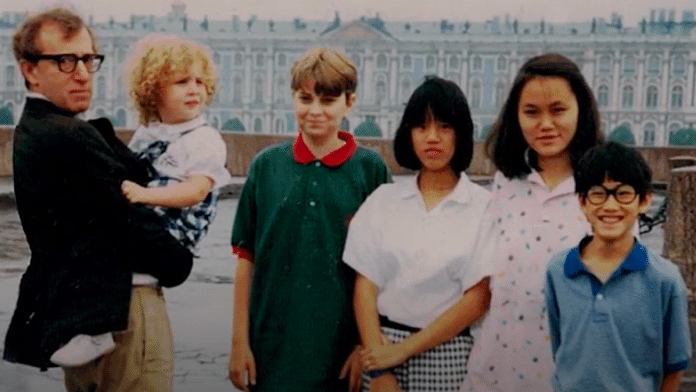

HBO’s Allen v. Farrow, a docuseries directed by Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering and available in India on Disney Hotstar, is unambiguously un-balanced, and that may not be a bad thing after all as we have been led to believe in populist times. Thankfully, the millennial era is also helping the culture at large shed its obsession with appearances. The protagonist at the heart of the four-part documentary, Dylan Farrow, is emphatic that she wants her voice to be heard, which, according to the documentary, was suppressed by a journalistic ethic preoccupied with appearing ‘fair’, and less concerned that someone powerful might be taking advantage of it.

When Farrow was a child, her adopted father, filmmaker Woody Allen, orchestrated the narrative around what happened to her at his hands.

In the doctrinaire shadow cast by ‘he said, she said’, we may want to re-examine the notion of balance, which requires a viewer, a reader, a listener to come to a conclusion after being subject to all points of view. This is also the foundation of all good journalism and drummed into the culture for years.

But that culture is now changing.

Also read: It’s time we believed sexual assault survivors because perpetrators rarely say #ItWasMe

Anita to Lorena

Professor Anita Hill received a call from Joe Biden in 2019, who wanted to express his regret for what she endured 28 years ago at the US Senate Judiciary Committee hearings for the confirmation of Judge Clarence Thomas to the US Supreme Court in 1991. That she was questioned by an all-White committee of men and that witnesses were not called to corroborate her account of sexual harassment by Judge Thomas was a sign of how the skewed power dynamic in the system worked against women, and according to Hill it trivialised the case into a high-pitched “he said, she said” debate.

But in the last decade, the global rise and spread of millennial discernment has been taking on the monolithic quality of some of these established networks and media houses. New ideas have earned currency like the one that says, what passes for balance may perhaps be false equivalence, and this may not always be about fairness or justice.

Allen v. Farrow depicts Allen’s powerful network in action in the 1990s. He was able to mobilise institutions — from the media to medical and state — to invalidate the veracity of his ex-partner and Dylan’s mother Mia Farrow’s testimony. But journalistic balance meant that both sides must have their versions reported. The uneven power dynamic, nor the idea that influence could play a role in the stories being written, was yet to shake the foundations of journalism. Networks and hierarchies of privilege operate everywhere from the personal to the professional. Although, #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter have surmounted the traditional bounds of these networks to an extent.

Thanks to #MeToo, formerly infamous names like Lorena Bobbitt or Monica Lewinsky no longer invite tabloid gasps. The Bobbitt case from 1993 was reported in newspapers around the world in grisly detail — a woman who cut off her husband’s penis after he allegedly raped her. The media was unable to treat the Bobbitt case as an instance of serial marital rape and domestic violence taking a horrifying turn, which is how the jury dealt with it. The sad story of what really happened to Lorena Bobbitt (now Gallo) is documented in Lorena, available in India on Amazon Prime Video.

Also read: Hashtags like #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter make people view the news as less important

Calling a spade

Although it is becoming harder to tell stories of femme fatales and ‘honey traps’ out to maim men’s reputations, and even with #MeToo, women are reluctant to name names fearing harsh reprisals from connected men. Journalist Priya Ramani tried to change that in 2018. On cue, she faced a backlash for her decision to name the person who made her more than uncomfortable during what was supposed to be a professional interview in 1993 — M.J. Akbar, who went on to become a Union minister.

The defamation case filed against Ramani, which Akbar eventually lost, is part of a playbook adopted by many powerful accused. A tactic employed by the accused to metamorphose into the victim in the public eye, is also a tool to stymie the real victim. Allen v. Farrow recounts how Woody Allen sued for custody of Mia Farrow’s children in 1992, a case he lost in 1993 after months of agony for the Farrow family.

By suing, the powerful instil a sense of deterrence in victims hoping for justice, in effect robbing them of their agency. But as Allen v. Farrow demonstrates, this also takes a financial and psychological toll on the victims’ families casting a pall of gloom over the rest of their lives.

It is left to the hidebound culture vulture to learn new habits of thought, groomed as we were by our time to believe that the truth came with complex flavours, as in your truth, my truth and everything in between, like ‘whataboutery’. The routine cognitive dissonance we experienced through the deployment of these cultural thought shortcuts was filed away in the back of the mind, till the dawn of a new age in which millennials dared to call a spade, a spade.

Allen v. Farrow has been made in a time that has freed us to take sides without the dread of appearing simplistic. In a ‘he said, she said’ confrontation, one of these may be the truth, and the other—shocker of shocks—not even true. A few years ago, this was not a sophisticated admission that could be made aloud. Just as Allen managed to convince an entire cohort of auteurs and journalists in the ’90s that they may be prudes if they didn’t portray his relationship with Farrow’s adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn as a new-age liaison to baffle the masses. He conned this same cohort into investing in the patriarchal narrative of the hell wrath of the woman scorned.

He may have just been a con man with a genius for narrative. Stripped of the sheen of art, ‘he said, she said’ was just something he peddled, and we bought. It may have just been another art of the deal.

The author was a journalist with The Indian Express, now a writer and gardening junkie based in Pune. Views are personal.

Allen v. Farrow has been made in a time that has freed us to take sides without the dread of appearing simplistic.

Great. We live in a culture where it’s fine to be almost childishly simplistic, even primitive, in our representation of a very complex world, and we no longer have to dread being called out on it.

And that’s a good thing…WHY?