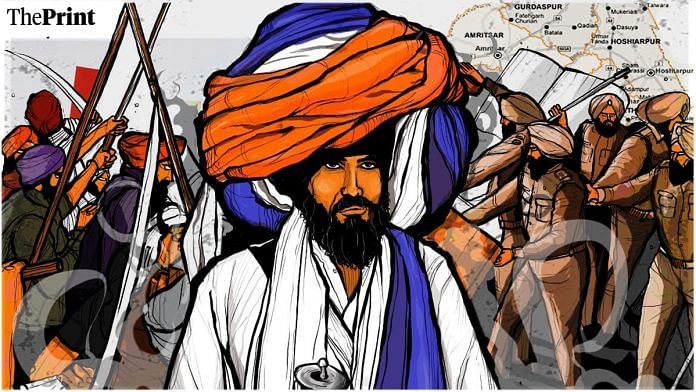

If the visuals we have seen from Amritsar these past couple of days — radical followers of the new charismatic preacher Amritpal Singh overrunning the Ajnala police station in Punjab — do not jolt us, it shows how indifferent and lazy we’ve become on critical issues of our supreme national interest.

They stormed a police station next to the border with Pakistan — as sensitive a zone as you can name. They forced the state to release one of theirs arrested for kidnapping. Watch those craven, grovelling videos of the Amritsar police chief saying that the protesters have proved that the charges were fake, and that the police were withdrawing the FIR.

Thank you sir ji, this is the new bleeding-heart Punjab Police we never thought we’d live long enough to see.

There were some such surrenders made by Punjab Police in the post-1978 epoch of militancy. But with a demonstration of embarrassment and helplessness. Now, it has been done with a straight face, with much relief. This, in a state where even an FIR for a fake bicycle theft charge is near-impossible to erase until a person’s death.

Not for three decades, in fact, not since V.P. Singh’s disastrous daily-wage government traded those arrested militants for then Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s daughter Rubaiya, have we seen a state capitulation like this one.

Think. A big police station right on the border was overrun by a mob armed with swords and firearms, an arrested suspect was freed, and then the state said ‘sorry, we were in the wrong’. You have to be nuts to imagine there will be no consequences for it. Nothing will please me more than to be proven wrong on this in the times to come. The cruel fact, however, is that we are repeating mistakes of a bad past in Punjab.

No government, not in Punjab, or even the Centre, probably focused, “sthitaprajna” (one with steady intellect) as we know from Mahabharat, on fighting Rahul Gandhi, has expressed much alarm yet. Escapism is no plan or solution. But, for what’s going on in Punjab, I find it impossible to avoid unleashing that awful cliche on you: we have seen this movie before.

The last time we saw it, say from 1978 to 1993, it was like a horror film that never ended. It consumed tens of thousands of innocent lives from all communities, though mostly Sikh and Hindu, saw countless assassinations, a controversial military operation at a scale never before (and hopefully never after), strained communal relations and caused a generation-long alienation. It took 15 years to begin the return of normalcy.

Now, much seems like the way troubles began on Baisakhi day, 13 April, 1978, except two differences. One, there was bloodletting and death that day as a group of Bhindranwale’s supporters protesting at a Nirankari sect congregation were fired at in Amritsar. By God’s grace, we haven’t seen violence even at a fraction of that scale now.

Also Read: In Kashmir 3 years on, 3 positive changes, 3 things that should’ve happened & 3 that got worse

If you are relieved with a sense of ‘so far, so good’, I underline for you the other difference. Bhindranwale never, ever used the word “Khalistan”. Never.

Many, many journalists met and interviewed him; I did so nearly 20 times in 1983-84 and he never mentioned the word. In fact, even the last time I saw him in his huddle with key lieutenants at the Akal Takht, his last appearance when the Army had already begun encirclement of the Temple Complex in Operation Bluestar, he did not ask for a sovereign state.

In his last weeks, as tensions were rising and a military-style operation was looking inevitable, he had changed his tone, but was careful with his words.

We asked him often — on the record — if he wanted Khalistan, or what he thought of the demand. He would say with a mischievous smile, “I never asked for Khalistan”. But if the “bibi” (the lady, as he referred to Indira Gandhi) gave it to me, I will not say no.

Amritpal Singh has been using that K-word from Day 1.

Of course, he packages it as simply a demand for self-determination, which he asserts should be anybody’s right in a democracy. Then he goes on to say that if Amit Shah says he will crush the “Khalistan movement”, he’d rather first remember the fate Indira Gandhi met for making the same boast.

Also Read: AAP’s filling a big vacuum in Indian politics. Question is how long it can sustain without ideology

Part of the old movie/new movie story is the politics of the state.

Punjab’s post-Independence history tells us that the state sees a crisis whenever it has a weak leadership; the leader seems controlled by Delhi and incapable of keeping Sikh religiosity in his political tent. The definition of ‘weak’ is particularly nuanced in Punjab and it isn’t determined by the size of an elected government’s majority. Or there’d be no issue now.

The state needs a strong individual as chief minister. The party in power also doesn’t matter so much. Partap Singh Kairon ran an effective Congress government from 1956 until Nehru erred and removed him under pressure in 1964. Kairon was assassinated on 6 February, 1965 on his way to Chandigarh on G.T. Road near Sonepat. Punjabi Suba (a separate state for Punjabi speakers, a code for Sikh majority), which had remained mostly dormant, sprang right back on the forefront. The state was divided in 1966.

Things were calmer for a few years until a Congress government under Giani Zail Singh took over in 1972.

Two things need to be noted. He was no strongman like Kairon, and he wasn’t a Jatt Sikh. He was a Ramgarhia, a caste that’s an OBC today. Which brings us to the second peculiarity of Punjab politics. It needs a strong leader, a Sikh, and a Jatt. In fact, Giani ji would often say ruefully that he might be the last non-Jatt chief minister of Punjab.

He tried his best to win over the Sikhs through his own pivot to religiosity. Among the more interesting, less remembered, but relatively harmless things he did was to bring to India from Britain “descendants of Guru Gobind Singh’s horses”. He then marched them in a ceremonial religious procession across the state, retracing the 10th Guru’s great journey. Huge crowds of the devout followed.

The second was ultimately disastrous. He looked for a deeply religious Sikh who’d embarrass the Akali Dal in the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) elections. That’s how he talent-hunted Bhindranwale. We know the rest.

The equally important point is that this phase of radicalism didn’t just begin with the arrival of Bhindranwale. Over a year after Zail Singh was sworn in, the Akali Dal had passed the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, 1973, demanding autonomy that would take them beyond where Article 370 had left Jammu & Kashmir. Again, the combination of a weak if wily non-Jatt leader controlled by Delhi had created the space for radicalism.

The Akali Dal came to power post-Emergency and then Indira Gandhi blundered again in dismissing Parkash Singh Badal’s second government using Article 356 once she returned in 1980. Darbara Singh now was weak and not even wily. He was totally run from Delhi, mostly by Zail Singh’s home ministry. This new space became the playground for Bhindranwale, though the bugle had been first sounded by the Akali Dal at Anandpur Sahib in 1973.

To sum up, Punjab needs a strong Jatt Sikh leader, one whose politics can subsume Sikh religiosity, and one seen to be his own boss, not run by Delhi. Among all of India’s states, Punjab, especially its Sikh population, has the strongest anti-Delhi (domination) sentiment.

From there, we have come to a stage of calm where nobody, not even an Akali Dal out of power talks about Anandpur Sahib resolution or autonomy. It’s at this juncture now, that we see the rise of a man who begins his conversations with the demand of Khalistan.

How and why has this space been created? Does Punjab have a strong leader? What happens if Punjab is seen to be governed from Delhi? Does today’s politics in the state have the ability to keep Sikh sentiments and religiosity in its tent? Can we calm this new wave of radicalism with free power, better schools and hospitals? Finally, can we do any of this when radicals can overrun our police stations and our top officers go out with public apologies instead of taking action? I leave you with these questions.

Also Read: Return of the Muslim: From Modi ‘sermon’ to Pathaan to Bharat Jodo Yatra