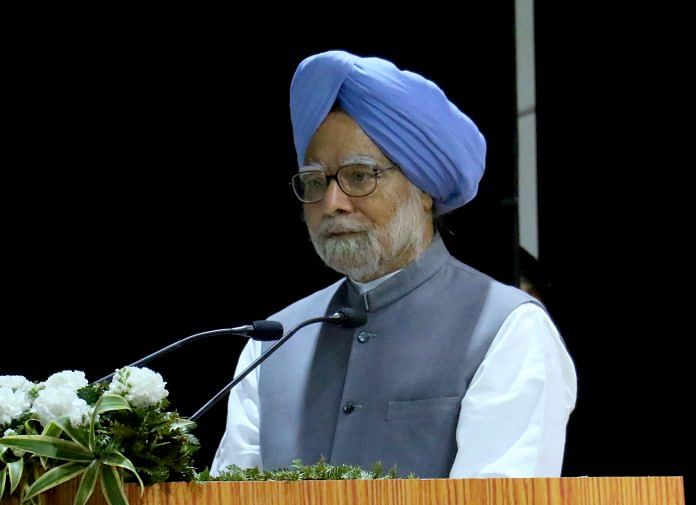

An essay in the latest Economist (May 29-June 4) that raises the question, “Who put the shine into India?” should be essential reading for our new MPs as they are sworn in. The essay traces India’s break out from the Hindu rate of growth and asks who made it possible, Dr Manmohan Singh and Narasimha Rao in 1991, Rajiv Gandhi in 1985-89 or his mother in 1980-84, after her post-Emergency exile when she returned unencumbered by the collective intellectual weight of her old, anti-west, pseudo-socialist cabal.

The answer is a complex one. Indira Gandhi, in her second avatar, had realised the perils of mere vote-catching populism and slowly began unshackling domestic enterprise from quota raj, also slipping in the first visible FDI in our history in the form of the Suzuki-Maruti collaboration. Rajiv followed by further relaxations and then, after what was mercifully only two years in the doldrums under V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar, we were back to reforming again now under Rao and Manmohan Singh. This phase, though, was more radical and created the formation for sustainable, long-term growth, reducing tax rates and duties, and at least bringing ideas like FDI, privatisation and infrastructure reform in our political and intellectual discourse.

What Indira and Rajiv did, argues the Economist, was to pluck the lowest of the low hanging fruit in the ’80s. Does it then follow that what the BJP/NDA government did in its six years was to pluck more low-hanging fruit in the second crop from the same reform tree? Possibly, but their record is a mixed one. They opened up aggressively in many areas, rationalised taxes further, freed up imports and foreign exchange greatly, actually sold some profit-making companies which have all done better subsequently. But, most important of all, it began the process of big-spending on infrastructure. It is a pity though that it moved a bit slowly in so many areas, from power to FDI sectoral caps and even civil aviation. Each one of these is now becoming a battle for the new incumbents.

But that is the basic nature of reform in India. If you actually believe (as I do) that reform began with Indira Gandhi in 1980, you would now be looking back at a quarter century of reform-led growth. It is also a truism that while we took the first 40 years after our independence to double our GDP, we doubled it again in the subsequent 15, and could do it even faster now if the CMP’s promise of 7-8 per cent growth is realised. The reform process, therefore, has been a continuous one and it should be tough to dispute the presumption that it must have bipartisan support. With every change in government the incumbent has handed over the baton to the successor, with unfinished agendas. The change has continued. In a quarter century now we haven’t seen a rollback except the brief Janata Dal interregnum when the then finance minister, Madhu Dandavate, once astounded the western diplomatic corps by telling them that while he did not mind FDI, “I will not go looking for it”. Since then leaders of every party from the BJP to the Left in West Bengal, Laloo to Chautala, Mulayam, Mayawati and Jayalalithaa, all have wooed FDI which, really, is the last frontier to be conquered by our mindset as it breaks out of nearly half a century of socialist indoctrination.

Also read: Manmohan Singh has economy advice for PM Modi — get rid of suspicion, trust Indians

The other continuing thread in this quarter century has been that the opposition to the reformer has almost entirely come from within. Indira Gandhi could override it partly with the force of her personality and partly because what she was doing was still so unobtrusive, mostly stealthy. She packaged the arrival of both Suzuki and Pepsi in complex agreements that befuddled even the most vigilant xenophobes in her power structure. But I believe that her most significant contribution was at a different, and most vitally fundamental, level. Our access to recent history is extremely limited so we do not know whether she had foreseen the end of the Cold War and Soviet decline. But even as she tacitly backed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, she acted pro-actively to end the freeze with the US. Her meeting with Ronald Reagan in October 1981 started a fundamental shift, not merely in our foreign policy, but in our entire worldview. In 1981, nobody (except, who knows, the Iron Lady herself) would have figured this. But could a democratic nation as emotionally complex as India have gone ahead with sweeping reforms, integrating with global markets and capital flows, if the US and the west were still seen as permanent adversaries? The “reform” of India’s foreign policy, and thereby our popular worldview, has gone on simultaneously with economic reform.

Changing age-old views, prejudices, suspicions and even commitments in India is a very complex process. It is not like a Lee Kwan Yu or Mahathir waking up one morning and issuing a diktat. The complexity is underlined by the way each set of reformers has been hobbled from within. Rajiv, as he hit the Bofors crisis midway through his tenure, was persuaded to not merely halt reform, but to hark back on the old mantra of US-bashing with that stunning “naani yaad dila denge” speech. Rao and Manmohan Singh were consistently opposed not merely by Arjun Singh ‘ who opposed everything in that cabinet anyway ‘ but also by the likes of Rangarajan Kumaramanglam (who later became a reformer of sorts after joining the BJP), Vyalar Ravi and even A.K. Antony, who produced a report, blaming his party’s 1996 defeat on economic reforms. Just for the record, it is now his turn to battle the Left in his own state to defend his own ADB-funded reforms.

The BJP-NDA years were no different, too. Through their six years there was no real opposition to any reformist policies from the real Opposition. The Left did not matter. The Congress was extremely constructive in voting for so many reformist legislations that many of the NDA constituents opposed. Almost all the opposition to reform came entirely from within. At one end of the spectrum, there was the RSS and Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, with its unreconstructed economic revanchism and retro-Gandhian fixation. At the other, were so many cabinet members who saw a security threat in all kinds of things, from increasing the FDI cap in telecom (while so many of them used Hutch cellphones) to privatising what were merely refining and retailing petroleum companies like HPCL and BPCL. Of course, all this righteousness was also heavily loaded with undertones of vicious corporate rivalries and lobbying. When Vajpayee looks back on what he started but left unfinished in his six years, he would regret deeply not putting his foot down on these five or six occasions when policy decisions ‘ already widely debated and accepted ‘ were blocked from within.

Also read: Manmohan Singh told me weeks before 1992 Budget speech that he’d have to resign

Manmohan Singh, therefore, should have a pretty good idea of what he should expect. One of the most cruelly ironical aspects of the history of our reform has been opposition from within. It comes partly from unevolved intellect, partly through inter-corporate lobbying and sometimes out of a sheer clash of political ambitions. The kind of opposition he may face from the Left, actually, will be more predictable and principled. He and Chidambaram will argue with the Left at a different plane, take some ground and concede some. The real trouble will come, as always, from within.

Yet, when both reflect on 1991, the difference should only encourage them. As both have acknowledged, the NDA has handed them over an economy that is sounder at a macro level than ever in our history. Inflation and interest rates are low, reserves plentiful, exports booming and, what is more important, several infrastructure projects, notably the highway building and port/airport/power sector modernisation, are already underway. To keep these going is merely the “lowest of the low-hanging fruit” Singh can pluck. His challenge would be to apply the connections to convince people deeper in the countryside that reform is even more important for them than for their richer cousins in the cities, find the money for some degree of populism and yet prepare the ground for the next generation of reforms that history, hopefully, would see as being even more significant than what he did with Rao in 1991.

Also read: How Manmohan Singh has become the go-to leader for the Congress to take on Modi