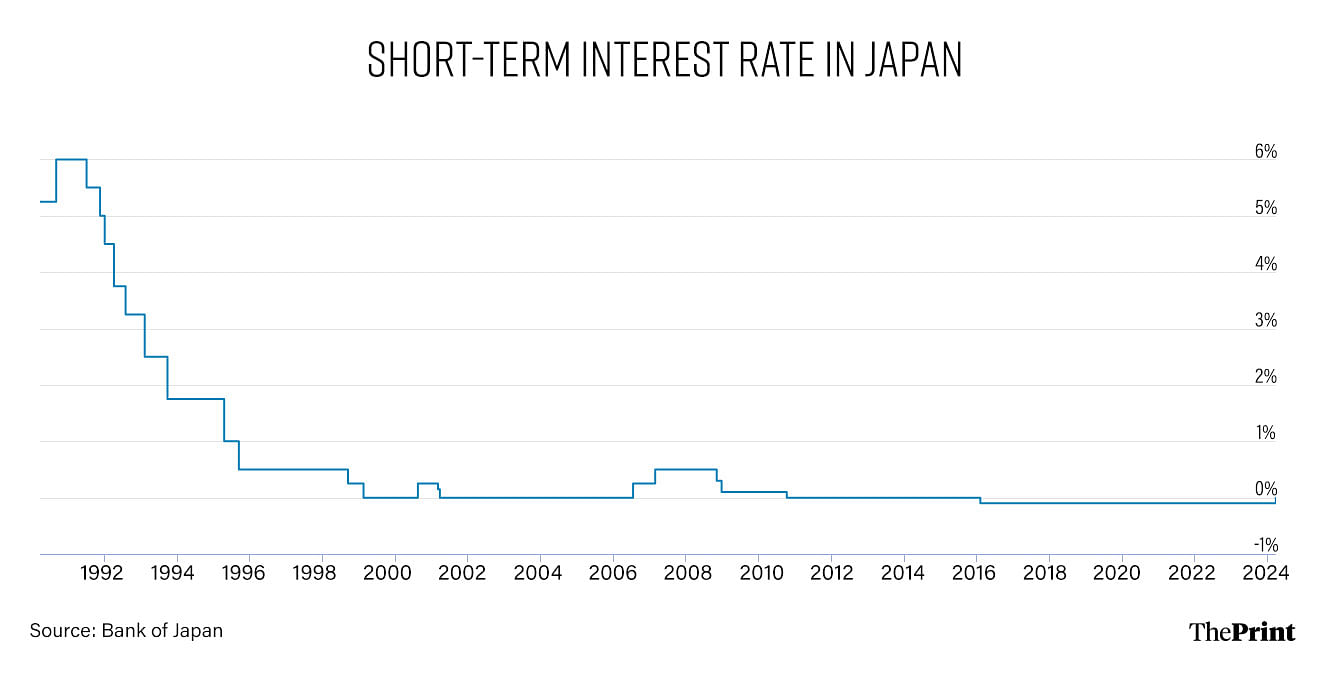

In its 19 March meeting, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) announced its first interest rate hike in 17 years. It set the overnight call rate as its new policy rate in the target range of 0-0.1 percent. The decision raised the interest rate from the previous held minus 0.1 percent. For the past eight years, Japan’s central bank has been following a negative interest rate policy to stimulate economic growth and combat deflation.

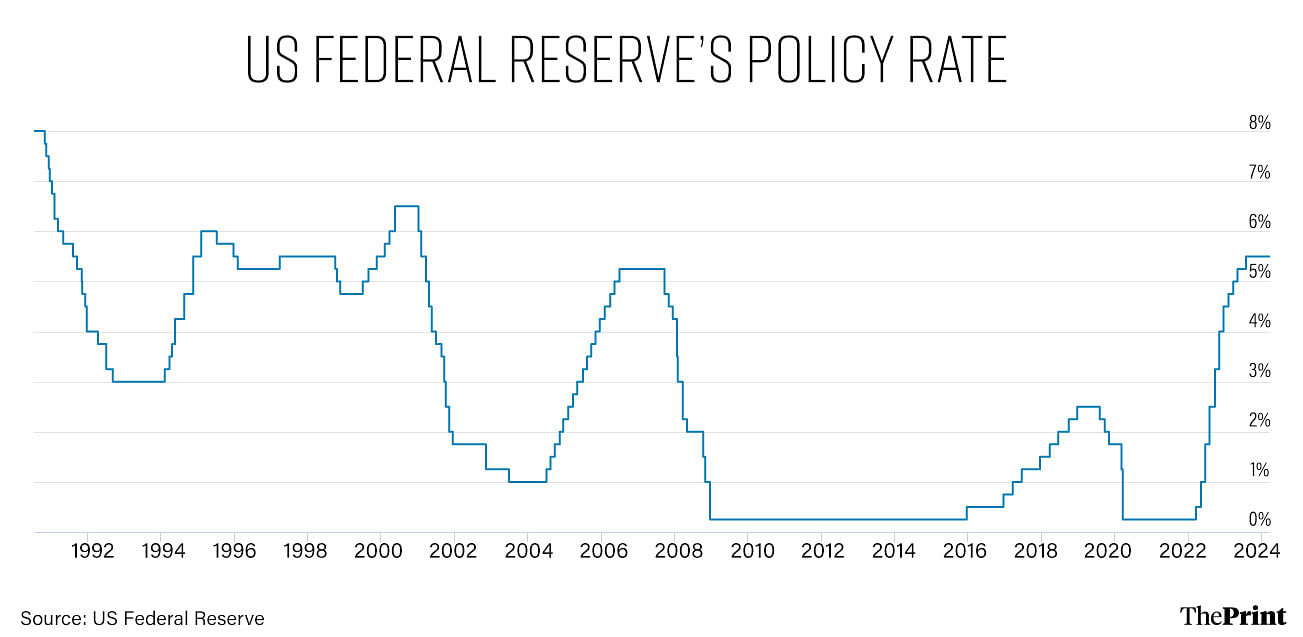

In contrast, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve, while maintaining a status quo on rates, have signalled that they will start the rate cut cycle this year.

Quantitative Easing, Negative Interest Rates and Yield Curve Control

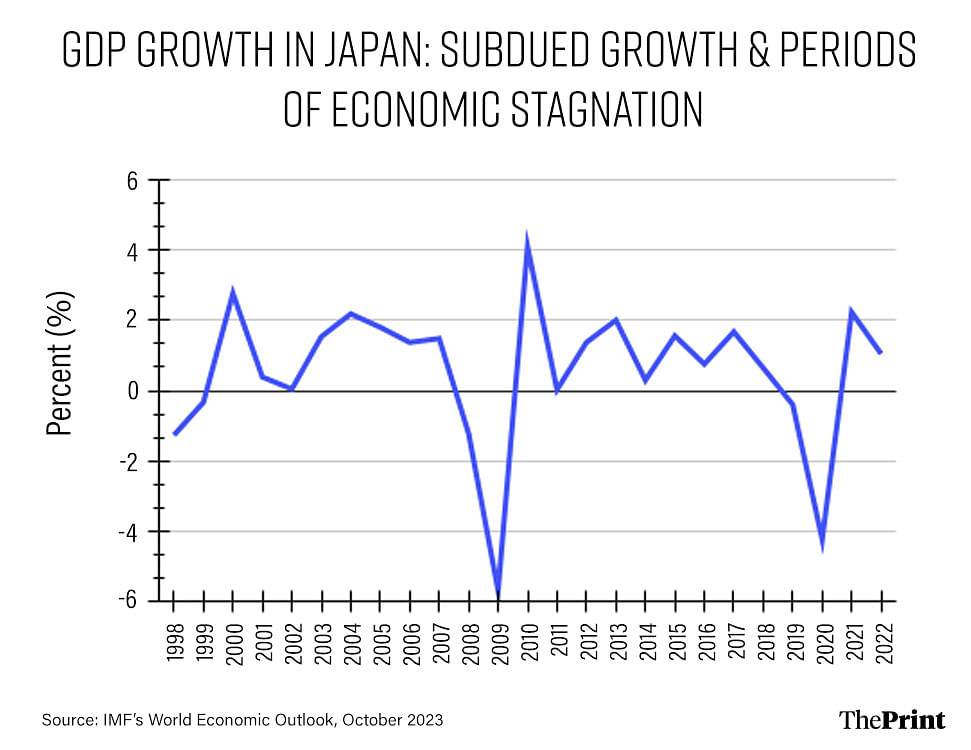

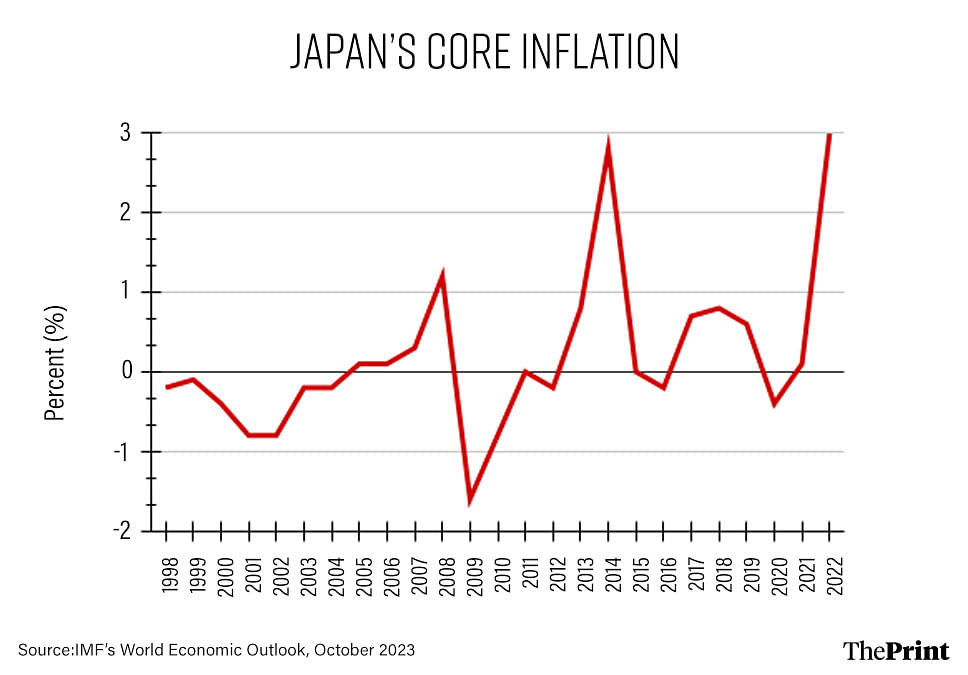

Since the late 1990s, the macroeconomic environment in the advanced economies posed challenges for the conduct of monetary policy. Visible demographic shifts, glut in savings and decline in productivity growth led to economic slowdown. The onset of the global financial crisis further accentuated economic stagnation and led to periods of sustained deflation. This was particularly true for Japan which faced periods of subdued growth and deflation.

In addition to the conventional response of cutting rates, many central banks resorted to unconventional monetary policy responses, that took the form of forward guidance and purchase of government bonds and other securities from banks and financial institutions. The objective of these measures, collectively referred to as Quantitative Easing (QE), was to encourage banks to provide more credit to the economy.

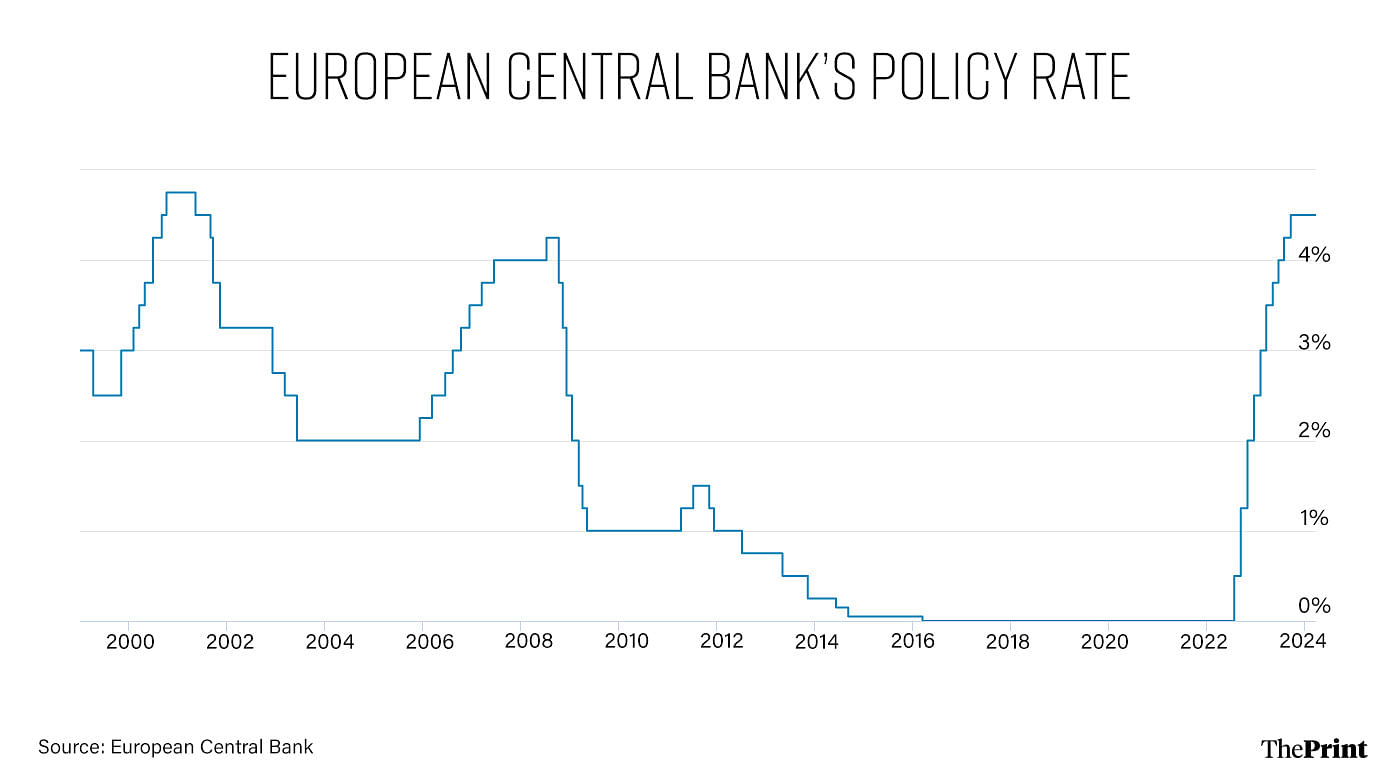

Some central banks went a step ahead and announced negative interest rate to discourage banks and financial institutions from maintaining reserves with their central banks. In 2014, the European Central Bank became the first central bank to implement negative interest rates. In subsequent years, many central banks such as Denmark’s Nationalbank, Sweden’s Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank all adopted negative interest rates to pump-prime the economy. Japan adopted the negative interest rate policy in 2016.

In addition to quantitative easing and negative interest rates, the BoJ, in 2016 introduced Yield Curve Control (YCC) as part of its policy toolkit to lift the economy out of deflation. Under the YCC framework, the Bank sought to control both short-term and long-term interest rates. The Bank stood ready to purchase Japanese Government Bonds to ensure that the yield does not rise above 0 percent. The Bank also decided to buy other securities such as corporate bonds, commercial papers, exchange traded funds and Japan’s real estate investment trusts.

Most of the central banks abandoned the negative interest rate policy in 2022 in light of the resurgence in global inflation in the aftermath of the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. The BoJ was the last central bank to exit the negative interest rate policy. As part of its exit from the negative interest rate policy, the bank also announced that it would abandon its YCC policy and would also end purchases of other securities.

Also read: Lower on food, higher on conveyance & durables — how consumption patterns changed in past decade

Reversal of the ultra-loose monetary policy

Despite a rise in inflation above 2 percent last year, Japan continued with its ultra-loose monetary policy as it was considered that the rise in inflation is imported and transient. The ultimate trigger for the unwinding of monetary stimulus was the rise in wages in the recent round of negotiations between the corporations and the trade unions. Japan’s biggest companies have agreed to raise wages by 5.28 percent-the heftiest pay hike in over three decades.

Global inflation, pent up demand and a labour crunch led to the jump in wages. The hike is expected to boost consumer demand and generate a more durable growth, paving the way for the reversal of the ultra-loose monetary policy. However, the bank officials did not give forward guidance on the future course of interest rates. Subsequent policy moves will depend on the trajectory of inflation and growth.

Potential implications of BoJ’s policy actions

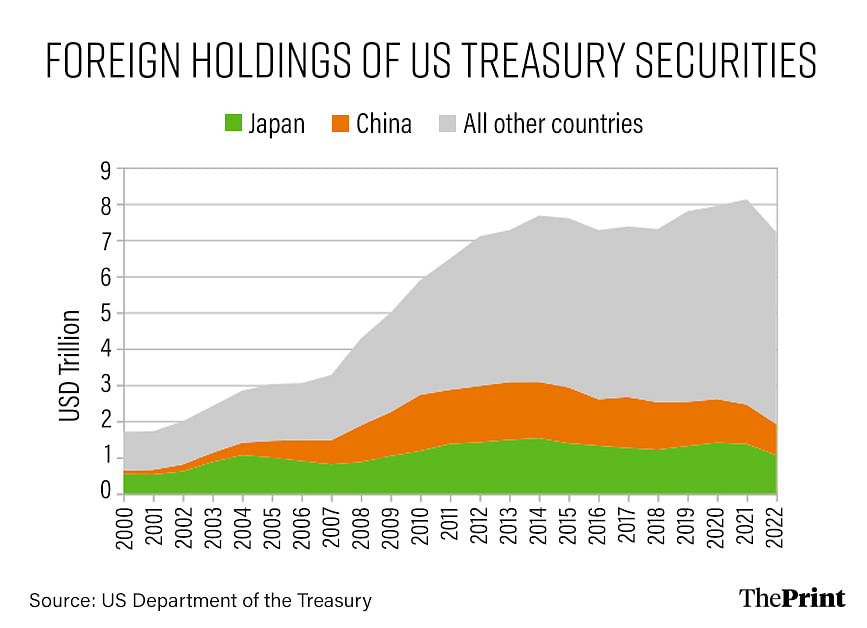

Japan’s investors are at present the biggest foreign holders of US treasury securities. As interest rates start to normalise (move into the positive territory), Japanese investors would be inclined towards investing at home. However, in the short-term, the impact on the global capital markets could be limited and more sustained rate hikes may be needed to trigger a significant reallocation of Japan’s capital.

Another implication could be on Japan’s borrowing costs. Japan’s public debt amounts to almost 265 percent of GDP. Japan has been able to maintain a high level of debt, in part, owing to its low interest rate regime. A reversal of the loose monetary policy could potentially have a destablising impact, owing to higher to higher interest burden for the Japanese economy.

European Central Bank kept rates unchanged, could lower inflation forecast

The European Central Bank (ECB) kept its rates unchanged in its monetary policy meeting on 7 March, 2024. The bank noted that interest rates are at levels that, if maintained for a sufficiently long duration, can bring inflation down to the ECB’s 2 percent target. In line with previous meetings, the ECB did not provide any forward guidance, instead favouring a data-dependent approach in setting rates.

Inflation has been revised downward from previous forecasts, primarily for 2024 (on account of lower energy prices). Inflation is now expected to be 2.3 percent in 2024, 2.0 percent in 2025 and 1.9 percent in 2026. Earlier projections for inflation (released with the December 2023 meeting) were: 2.7 percent for 2024, 2.1 percent for 2025 and 1.9 percent for 2026.

Status quo on rates by the US Fed with indications of three rates cuts

The US Federal Reserve announced a status quo on rates but signalled that it expects to cut rates three times this year. The delay in cutting rates is on account of the solid pace of expansion in economic activity even though inflation has eased from the highs of 2022. Latest figures show that inflation at 3.2 percent is still some distance away from the 2 percent target.

To conclude, while the US Fed and the European Central Bank will consider monetary easing, the Bank of Japan will look at maintaining the positive interest rate regime in line with the incoming data on inflation and growth. These could have implications for exchange rates and global capital flows in the medium to long-term.

Radhika Pandey is associate professor and Utsav Saksena is a research fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), New Delhi.

Views are personal.

Also read: Shortfall in central grants to poor quality of expenditure — what budgets of Bihar, Punjab & UP show