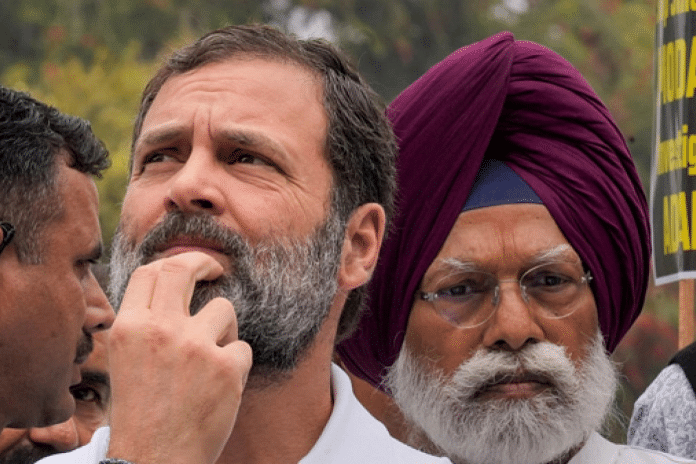

New Delhi: Congress MP Rahul Gandhi was disqualified from the Lok Sabha after a Surat court convicted him in a defamation case for his remarks made at a pre-election rally in 2019.

“Consequent upon his conviction by the Court of Chief Judicial Magistrate, Surat… Shri Rahul Gandhi, Member of Lok Sabha representing the Wayanad Parliamentary Constituency of Kerala stands disqualified from the membership of the Lok Sabha…,” read the order released Friday by the Lok Sabha Secretariat.

Though the Chief Judicial Magistrate in Surat sentenced him to two years imprisonment Thursday, it permitted bail on a surety, and allowed him to appeal against the judgment.

As the law stands, Rahul remains disqualified until his conviction is stayed by a higher court.

Under Section 8 of the Representation of People Act, Rahul is barred from the date of his conviction “for a further period of six years since his release”. This means that if the court order were to stand, it would disqualify him for a cumulative period of eight years, including the jail term handed by the court. It also means Rahul may be unable to contest in the 2024 Lok Sabha election.

This year, another sitting Lok Sabha MP faced disqualification after being convicted in a criminal case. On 11 January, Lakshadweep MP P.P. Mohammad Faisal was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in jail. Two days later, he was disqualified from the Lower House of Parliament.

Though the Kerala High Court stayed his conviction on 25 January, the Election Commission had announced bypolls in his constituency. Faisal reached the Supreme Court which stayed the EC order.

Subsequently, the Union Law Ministry recommended his reinstatement following which the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) MP is awaiting the Lok Sabha Speaker’s nod to attend Parliament.

ThePrint explains the law on disqualification of elected lawmakers in case of a conviction in a criminal case.

What law says?

The Representation of People Act, 1951 provides for disqualification for conviction in criminal cases. It provides for disqualification in cases of offences like rape, terrorism, communal disharmony etc. In such cases, a mere conviction is enough to disqualify a legislator from Parliament.

Section 8 (3) of the Act further provides a second set of offences for disqualification. It states that a mere conviction will not result in disqualification but requires the court to hand in a sentence of at least two years for disqualification under the provision. This is applicable in Rahul’s case.

At the same time, Section 8 (4) states that a disqualification “shall not take effect” until the lawmaker’s appeal against the decision is decided by the appellate court. This appeal, however, must be moved within three months.

Under Article 102 of the Constitution, a member of the Lok Sabha or Rajya Sabha can be disqualified under five circumstances: holding an office of profit, insanity, insolvency, citizenship, and disqualification by law. One may also be disqualified for ‘defection’ under the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution, which is desertion of one’s political poverty.

Also Read: ‘Rahul’s koshish Vs Modi’s sajish’: Congress says Gandhi paying for Bharat Jodo, Adani row

Preventing criminalisation

In 2005, the Supreme Court noted that the purpose of such disqualification in the Act was to prevent the “criminalisation of politics”.

“The purpose of enacting disqualification under Section 8(3) of the RPA is to prevent criminalisation of politics. Those who break the law should not make the law. Generally speaking, the purpose sought to be achieved by enacting disqualification on conviction for certain offences is to prevent persons with criminal background from entering into politics, and the House — a powerful wing of governance,” the top court had said in the K. Prabhakaran vs P. Jayarajant ruling.

It had noted the Act did not provide for immediate disqualification because that would affect the strength of membership of Parliament as well as the political parties in such cases. “Such reasons seem to have persuaded the Parliament to classify the sitting members of a House into a separate category,” the apex court noted.

In essence, the top court upheld Section 8 (4), which had provided an apparent waiting period of three months before disqualification was possible.

Lily Thomas Vs Union of India

However, just eight years later, the Supreme Court took a different stance in the landmark Lily Thomas case. It held that Parliament could not have given the three-month leeway under Section 8 (4) of the Act, because the Constitution was unequivocal on immediate disqualification.

In the case, senior advocate Fali S. Nariman on behalf of advocate Lily Thomas had argued that the requirements for an individual to continue as a member of the State Legislative Assembly and Parliament cannot be different.

On the other hand, Additional Solicitor General Siddharth Luthra contended that due to the frequency of acquittals and because it had been held constitutional earlier, the appeal had no merit.

But the top court struck down Section 8 (4) of the Representation of the People Act, saying that the date of disqualification could not be deferred. This meant that convicted lawmakers would be disqualified immediately.

Interestingly, Rahul had himself rejected an ordinance — which he called as “complete nonsense” — brought in by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government which attempted to nullify the ordinance.

Lok Prahari vs Election Commission

More recently, in the Lok Prahari case in 2018, the petitioner had approached the Supreme Court praying that an MLA should be disqualified regardless of a stay granted by the appellate court.

In its public interest litigation, NGO Lok Prahari contended that once a disqualification is incurred under Article 102 or 191 of the Constitution, the seat becomes vacant from the very day of conviction. The NGO argued against setting aside disqualification in case conviction of a lawmaker is stayed.

However, the apex court opined that once the conviction has been “stayed during the pendency of an appeal, the disqualification which operates as a consequence of the conviction cannot take or remain in effect.”

It further rejected the NGO’s contention that a higher court does not possess the power to stay the conviction.

“Clearly, the appellate court does possess such a power. Moreover, it is untenable that the disqualification which ensues from a conviction will operate despite the appellate court having granted a stay of the conviction,” the top court held, terming the law “well settled”.

Akshat Jain is a student at the National Law University, Delhi, and an intern with ThePrint.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: ‘Surname was Bhootwala, but caste Modi’ — BJP MLA behind Rahul defamation suit changed name in 1988