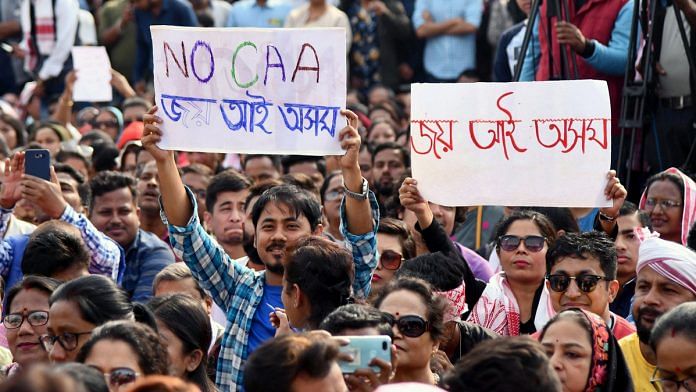

New Delhi: Ever since the Citizenship (Amendment) Act was passed by Parliament on 11 December 2019, it was met with protests all across the country. The new law was challenged in the courts almost immediately, with the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) filing a petition against it in the Supreme Court the day after its passage.

The CAA came into effect on 10 January 2020, while petitions against it kept mounting in the Supreme Court registry. Currently, there are over 140 petitions tagged to the IUML petition. Even the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, filed an intervention application against the law last year, offering to assist the court as amicus curiae.

However, the petitions have since seen little movement, with the case coming up before the Supreme Court thrice. The apex court has also refused to pass an interim order staying the law without hearing the Centre, which took 2.5 months to file its first response to the petitions.

Also read: With no Constitution bench set up yet, challenges to demonetisation now an ‘academic exercise’

What the law states

In India, citizenship is regulated by the Citizenship Act, 1955. The 2019 Act amended this law.

The amendment makes illegal migrants eligible for citizenship if they (a) belong to the Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian communities, and (b) are from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan. It only applies to migrants who entered India on or before 31 December 2014. Certain areas in the Northeast are exempted from the provision.

In simpler words, the amendment fast-tracks Indian citizenship for these categories of people, while for everyone else, the usual citizenship route laid down by the 1955 Act applies.

The 1955 law allows a person to apply for citizenship by naturalisation, if the person meets certain qualifications. One of the qualifications is that the person must have resided in India or been in central government service for the last 12 months, and at least 11 of the preceding 14 years. However, the amendment reduces the residency requirement for the specified categories to five years.

The statement of objects and reasons attached to the 2019 Act attempted to explain the rationale behind it, saying: “The constitutions of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh provide for a specific state religion. As a result, many persons belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities have faced persecution on grounds of religion in those countries.”

Also read: Review pleas pending, 7-judge bench not formed — Aadhaar Act validity case languishes in SC

Numerous petitions

Apart from the Kerala-based political party IUML, the petitioners challenging the law include Trinamool Congress MP Mahua Moitra, Congress leader and former Union minister Jairam Ramesh, All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) leader Asaduddin Owaisi, Congress leader Debabrata Saikia, NGOs Rihai Manch and Citizens Against Hate, advocate M.L. Sharma, and law students, among others.

In January last year, Kerala also filed a suit under Article 131 of the Constitution, becoming the first state to challenge the CAA. Article 131 empowers the Supreme Court to hear disputes between the government of India and one or more states.

The petitions challenging the law base their arguments on numerous announcements made by Union Home Minister Amit Shah that a National Register of Citizens (NRC), on the lines of the exercise conducted in Assam, would be drawn up across the country. For instance, on 20 November 2019, Shah spoke in the Rajya Sabha, saying NRC would be implemented nationwide, but assured that “no one from any religion should be worried”.

The petitions go on to highlight the impact of the CAA when coupled with the NRC. The IUML plea, for example, asserts “the passage of the Amendment Act, and the nationwide implementation of NRC… shall ensure that those illegal migrants who are Muslims shall be prosecuted and, those illegal migrants who are Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians such shall be given the benefit of naturalisation as an Indian Citizen”.

The petitioners also contend that CAA violates Article 14 (equality before law), which guarantees equal protection of the laws “to any person”, and not just citizens. They also challenge two classifications of the new Act — one that identifies six communities but leaves out Muslims, and the second that applies to persons from just three countries.

Several petitioners also challenge four notifications issued by the Centre in 2015 and 2016 on the same grounds. These notifications exempt illegal migrants from the above six religions and three countries of origin from deportation and detention under the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920, and Foreigners Act, 1946.

The amendments have also been attacked on several other grounds, including violation of secularism, Articles 21 (right to life), 15 (prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth) and 19 (right to freedom), as well as provisions on citizenship and constitutional morality.

Mahua Moitra’s plea says the Act is a “divisive, exclusionary and discriminatory piece of legislation that is bound to rend the secular fabric irreparably”.

‘Uppermost in everyone’s minds’

The pleas against the CAA first came up for hearing in the Supreme Court on 18 December 2019, with an array of several senior advocates — Kapil Sibal, Indira Jaising, Salman Khurshid, Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Mohan Parasaran, R. Basant, Sanjay Hegde, Menaka Guruswamy, Rajeev Dhavan, Shyam Divan and Jayant Bhushan — representing the petitioners.

Several lawyers urged the bench, comprising Chief Justice S.A. Bobde and Justices B.R. Gavai and Surya Kant, to issue a stay on the law and begin hearing the matter immediately.

However, the bench was keen to hear the matter after the winter vacations and only issued a notice to the government. It then posted the matter for 22 January 2020. That day, it refused to stay the Act, even though it said the matter was “uppermost in everybody’s mind”.

The bench allowed the lawyers to briefly present their preliminary arguments. Sibal, Dhavan and Singhvi pushed for the court to first decide whether the matter should be referred to a Constitution bench, before hearing the case on merits. Sibal submitted that the court can, in the meantime, pass an interim order to postpone implementation of the CAA by a few months.

Attorney General K.K. Venugopal, however, opposed any form of stay or interim relief, demanding that the Centre should first be allowed to file its reply.

The court agreed with Venugopal and directed the Union to file its reply within four weeks. In the meantime, it ordered that no high court should take up any similar matters involving CAA.

Additionally, the court also asked the registry to list petitions against CAA under two separate categories — one category of matters pertaining to Assam and Tripura, and the other pertaining to the rest of the country. This was after the petitioners from Assam and Tripura submitted that the court ought to treat their cases separately. They argued that implementing the CAA would irreversibly alter the demographics of Assam, as there are a large number of Hindu refugees from Bangladesh settled in Assam.

The main case came up on 18 February too. At that time, new petitions had been filed, so those petitions were asked to be served on the Centre. Since then, more petitions have been filed, and have been directed to be tagged with the same matter, but no proper hearing has taken place.

Also read: RTI, triple talaq, UAPA — petitions linked to 3 key matters heard only once in SC since 2019

‘No urgency’

Sanjay Hegde told ThePrint that the apex court did not take up this case on “high priority” when it came to demands for an interim stay order.

“The court, like in the demonetisation matter, does not seem to have taken up this case on high priority, at least in terms of an interim order, which would have done much to quieten the situation,” the senior advocate said.

“You may recollect that when Mandal (Commission recommendations) came and there was a nationwide uproar, it was the Supreme Court’s interim order which calmed the situation, notwithstanding the fact that ultimately, two years later, the Supreme Court upheld Mandal. Sometimes, the very act of actively doing something in a hearing sends a larger message to the country to bring down temperatures,” Hegde added.

When urgent listing of CAA petitions was sought in March, CJI Bobde had said that he will list the matter after the arguments in the Sabarimala case, which he said would be heard from 16 March 2020. But Sibal insisted that the case needs to be heard only for two hours so that interim relief can be provided. The court then asked him to mention the case after the Holi break, which was to end on 16 March. But the case has not been heard since.

On 5 March, when Sibal mentioned the matter, he also pointed out that the Centre had not filed its response to the petitions. Venugopal then told the court that the reply is ready and will be filed within two days.

The central government finally filed a counter-affidavit two and a half months after the petitions were filed, on 17 March, according to the Supreme Court website. In this affidavit, accessed by ThePrint, the Centre asserted that “history clearly depicts that persecuted minorities in the said three countries were left without any rights and the said historical injustice is sought to be remedied by the amendment without taking away or whittling down the right of any other person”.

With regard to contentions that the CAA violates freedom of religion under the Constitution, the Centre claimed that the law in fact does the exact opposite. It said that “rather than breaching any principle of ‘freedom of religion’, the CAA seeks to protect the ‘freedom of religion’ of the classified communities who have been persecuted for exactly expressing and practicing their respective religions in the particular neighbouring countries”.

As to the argument that Muslims have been specifically excluded, the Union noted that CAA excludes even Tibetan Buddhists from China and Tamil Hindus from Sri Lanka. Therefore, it asserted that the argument that it is designed to exclude Muslims is unfounded.

It, in fact, said the CAA furthers the Indian ideals of secularism, submitting, “the recognition of religious persecution in the particular neighbouring states, which have a specific state religion and long history of religious persecution of minorities, is actually a reinstatement of Indian ideals of secularism, equality and fraternity”.

Also read: 4 pleas, 15 dates and an interim order — electoral bond case hangs fire in SC for over 3 yrs