Champhai: Barely a kilometre from the border town of Zokhawthar in Mizoram’s Champhai district, guerrillas of the Chin National Army (CNA), an ethnic armed organisation, trudged steadily through the dusty roads of Khawmawi town in Falam district of Myanmar’s Chin State.

A sense of patriotism and pride was evident in their gait, as they interacted with local residents, petted dogs, huddled at the newly set-up office for the resistance groups, and passed time by the scenic Rih Dil lake, about 3 kilometres from Zokhawthar. A Chin guerrilla stood guard at the entry point of the bridge over the Tiau river, connecting Myanmar and India.

The resistance fighters have been exploring the border area surrounded by tree-covered hills and gauging the mood of the people in the trading towns of Falam.

But that’s one side of the story. The civilian population at the border town remains fearful of the war between the Myanmar military and the resistance forces — unable to predict the future and not knowing whom to trust. “We are reluctant to share our thoughts because we don’t know whom to confide in. Some support the military and some are with the resistance groups,” said a salon owner at Khawmawi on condition of anonymity.

Myanmar has been in the throes of civil war since 1948. It was under military rule between 1962 and 2011. In February 2021, the military wrested power again after toppling Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government. Now, the junta, as it is called, could be facing its biggest threat yet, in the form of a sustained attack on multiple fronts by ethnic armed groups that include pro-democracy fighters. On 27 October, this alliance of anti-junta forces — called the Three Brotherhood Alliance — launched coordinated attacks on military posts and captured several border towns, in what they call ‘Operation 1027’. The attacks have continued since.

Last month, Myanmar’s anti-military resistance forces, including the CNA, targeted security outposts in the Chin State. The violence saw hundreds cross over to India for safety, about which India expressed concern last week, but reiterated its support for a return of democracy. Those who stayed, are conflicted about whom to side with, and those who left, aren’t sure when they can return.

Last week, Mizoram’s newly sworn-in chief minister Lalduhoma said his government would continue to provide a safe haven to refugees from Myanmar.

At least 30 Myanmar army soldiers were at the company headquarters in Rihkhawdar — a town adjoining Khawmawi — before it was overrun by the Chin Defense Forces (CDF) and allies on 12 November. Another 40-50 were thought to be at the temporary camp or the Tiau camp of Khawmawi village that was captured the same day.

The aerial bombings and intensive shelling near the border settlements forced both military and civilians to flee across the Tiau. The joint operations were carried out by five resistance groups comprising about 150 Chin fighters — the CNA, CDF-Hualngoram, CDF-Zanniatram, People’s Defence Force (PDF)/PDA-Tidim and the drone team of CDF-Thantlang.

On the night of 26 November, the victory signage of ‘Welcome to Chinland’ that was placed atop the Indo-Myanmar friendship bridge was brought down. There were “several concerns” because of the signage, as it had gathered media attention, said one of the Chin fighters.

Instead, three Chin national flags were put up. The Hornbills that symbolise Chin identity swayed in the winter breeze, carrying news of new visitors to the ‘Liberated Zone’ — a term used to indicate relatively secure places, free of military rule.

The guerilla fighters are pleased with the response from the civilian populations of Khawmawi and Rihkhawdar towns.

“We have come from different districts. From the time we captured the camps and today — there’s a lot of change. They support us 100 percent and stand with us,” said 23-year-old Captain Nehemiah of the CNA who hails from Thantlang.

“Some even invite us home,” said 19-year-old Kyawlin, another CNA resistance fighter.

Also Read: Myanmar traders dodge bullets & bombs to sell in Manipur’s Moreh market. But no one’s buying

‘Some are brave, some very scared’

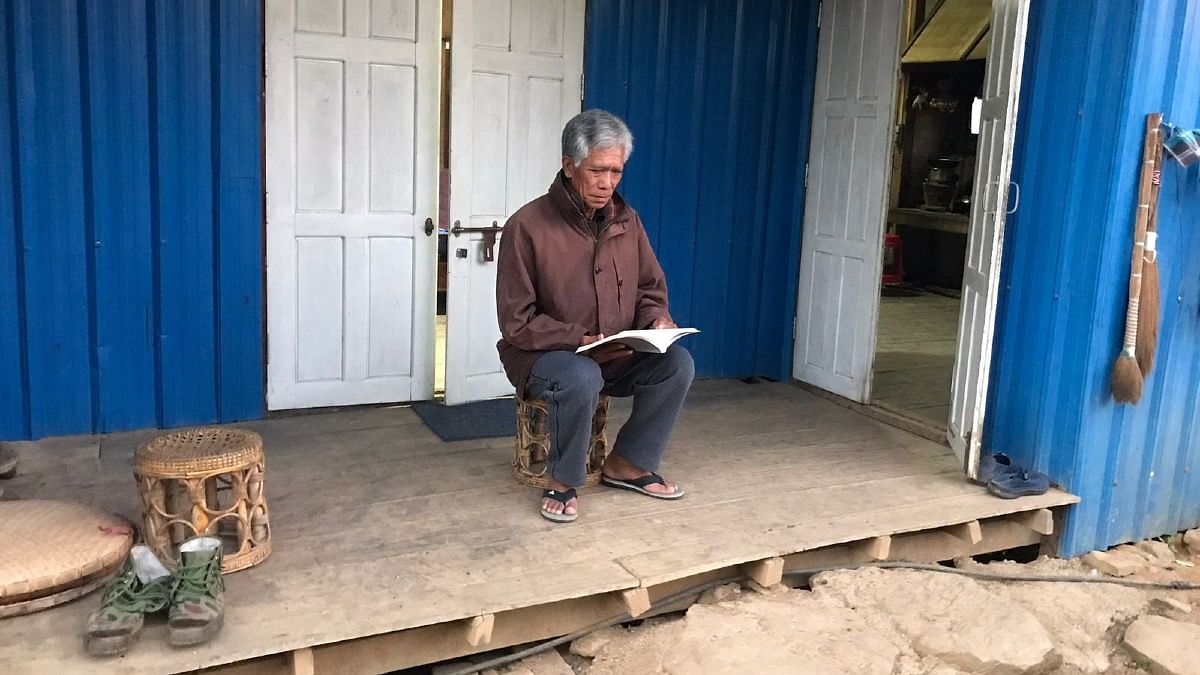

A retired government teacher and pastor of the Evangelical Methodist churches in Rihkhawdar, Reverend Lalsawichuanga, who has lived in the town for the past 36 years and travelled extensively across Myanmar and India for work, remembered the situation in 1993 — when the reign of the Tatmadaw (now Sit-Tat), Myanmar’s military elite, passed into its sixth year.

“When the military took power in 1993, the soldiers at the Rihkhawdar camp commanded villagers to build a fence and clean the compound. They always engage us for such purposes including making punji sticks for booby traps. Even though they didn’t disturb much then, our freedom was restricted. I had once gone to the jungle to shoot birds, the junta accused me of targeting them with my catapult,” Lalsawichuanga recalled.

For the 72-year-old churchman, democracy has since endured enormous setbacks because of “the military regime and its misdeeds”. But over time, he said, the villagers had grown accustomed to the military’s presence, which fostered a sense of “mutual understanding” — so much so that when all his neighbours and family members had fled into Zokhawthar, Lalsawichuanga and his son-in-law stayed back.

“Since the villagers learned about the fighting, they ran, but the junta never targets this area. We felt safe. We are used to the sound of guns,” he said.

The pastor narrated his ordeal when fighting erupted and Rihkhawdar turned into a battlefield. Before it all started, the Reverend had sent his wife and children to Zokhawthar. “The night of 12 November — it was a Sunday and we were supposed to go to church, but we were alerted by the local youths. We stayed home and slept off. Though we could hear the gunfight, we slept it through. That night, my wife and children kept calling, asking us to come to the other side. But I stayed put,” said Lalsawichuanga.

He added: “The next morning, almost all the villagers had fled. Some of them suffered bullet injuries in cross-firing. Only I, my son-in-law, and another villager were left thinking. The gunfight stopped after a few hours at the Rihkhawdar camp, but continued at the Tiau camp. We saw fighter jets and assault helicopters twice that day. I finally moved out and joined my family at Zokhawthar.”

Lalsawichuanga’s neighbour, 41-year-old K Moia from Sagaing Region, said the military did not disturb the people because the “village chief and the youngsters have good understanding with the junta”.

“Even before the war, there was regular firing. We live close to the junta camp, but we felt protected. We returned home immediately (from Zokhawthar) as the situation looked calm,” he added.

Lalsawichuanga, however, admitted that the people do not have close relations with the military — for a lot many reasons. “The water supply pipe to our village runs in front of the military camp. The junta personnel had put a bomb inside the pipe to prevent us from checking it. When we asked, they pretended not to know about it. Before they fled, the soldiers informed us that they put bombs here and there, without revealing the exact locations. We don’t know where they are. Water supply is still affected,” he said.

The two Rihkhawdar neighbours remain alert. The brief silence in the town can be broken by the sound of roaring jets anytime, they presumed. “I don’t feel much afraid of retaliation, but we are cautious — because junta jets have always dropped bombs on captured bases,” said Lalsawichuanga.

“Some people are brave, but some are very scared. That’s why they escape into India and find Zokhawthar safe,” said Moia.

He reminded that the main centres of Kalay, Hakha, Falam and Tedim remain under military rule. “I don’t feel very safe because the main centres of the military are not captured yet. If those places come under the PDFs, junta would certainly drop bombs in Rikhawdar. This is the border trading town and important for the military.”

‘Not sure when to return’

For the residents of villages on the Myanmar side of the border, India is not a foreign country. Ties of ethnicity and kinship bind communities on both sides of the Tiau river. Chaw and Arsa (rice and chicken) are served in restaurants on either side. There’s fish, duck and even octopus that comes in from Kalaymyo (Kalay) in Sagaing Region, bordering Chin State.

Business has been affected — a few shops were open, but there were fewer customers. Local residents working at pubs and eateries waited to serve visitors.

Following the recent airstrikes, more people have streamed into Zokhawthar, three kilometres from Rih Dil lake.

There’s a popular saying among the Mizo and Chin people, something they have learned in school — “Rih Lake is the largest lake in Mizoram, but it is in Burma”. The heart-shaped lake is a revered site for the communities living in both India and Myanmar.

“Our ancestors lived by the Rih,” said a local resident in Aizawl. People believe the lake is home to the spirits.

According to the Champhai district administration, a total of 1,012 people fled to Zokhawthar on 20 November. They hail from Rihkhawdar, Khawmawi, Haimual and peripheral villages of Falam.

Since the coup in February 2021, as many as 6,201 displaced of Myanmar, including women, children and the elderly, have been living in temporary shelters, rented houses, or with their relatives on the Indian side of the border in Zokhawthar. Many have returned to their country, while others are unable to decide.

“We are not sure when to return. Because we don’t know what will happen next. We have to be here till the conflict is over,” said 70-year-old Lalruatthanga from Rihkhawdar, who has been living at a relief camp in Zokhawthar since March.

He added: “In other camps at Zokhawthar, there have been some issues like theft. But here (our camp), we haven’t faced any problem. The locals are good to us, and kind too.”

The district administration is currently undertaking a survey across nine villages of Zokhawthar to ascertain the “actual number” of people in the camps. Earlier in April, the biggest shelter for displaced Myanmar nationals in Zokhawthar was shifted from a field near the Tiau river to higher ground — to provide for a tolerable winter. The camp is equipped with electricity and water supply.

Also Read: ‘Northeast will change in coming decade’ — Jaishankar on border infrastructure push

Life of refugees, among the host population

Speaking to ThePrint, Champhai Deputy Commissioner James Lalrinchhana said that the authorities are spreading awareness among camp inmates on how to live together with the host population.

“We have held many awareness camps across the district for the displaced people of Myanmar. We have to teach them how to stay with us, how to live among us. There are many differences in lifestyle…The Young Mizo Association (YMA) is doing a very fine job of taking up these issues with the displaced people,” he said.

However, Lalrinchhana sounded a word of caution. “As of today, we are doing just well. But it would be of concern if this goes on for years and years. The main thing is for Myanmar to have peace and their natives to go back to their homeland. We are doing all we can, even providing education to the children. When it comes to food, the NGOs pitch in, and the society contributes whatever is possible. Some are staying with their relatives, so it eases things to an extent.”

“In terms of work, only temporary things are allowed. They cannot be here permanently. Mostly, they are engaged as labourers in construction sites. Some have good skills,” he added.

The location of certain camps has made it feasible for the administration to connect them with spring water from the mountains. The existing infrastructure would not have been adequate for both the host population and those taking refuge in the border town — if natural mechanisms were not in place, explained Lalrinchhana.

Vanluaia (58), from Rihkhawdar town, had joined neighbour Lalruatthanga’s camp at Zokhawthar in March. He hoped that the new Mizoram government would let them “live peacefully without bias”.

“The airstrikes can happen anytime in our area. We used to do farming for our livelihood. Now, we cannot return to do the same work as before. We expect the newly sworn-in Mizoram government to ensure peace and justice as before, without bias. We wish to live a better life,” he said.

Soon after his victory, Zoram People’s Movement (ZPM) leader and new Mizoram CM Lalduhoma told reporters that his government would continue to provide shelter to the refugees from Myanmar and Bangladesh, and displaced people from Manipur on humanitarian grounds. He is expected to meet Home Minister Amit Shah and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar in New Delhi soon to discuss the matter.

According to state home department data, more than 31,300 Myanmar nationals and over 1,100 Bangladeshi nationals are currently taking shelter in Mizoram. But the numbers could be much higher on ground.

Rihkhawdar now a ghost town

The Chin fighters’ capture of military camps at Myanmar’s Rihkhawdar and Khawmawi areas a fortnight ago are an embarrassing setback for the Sit-Tat (Myanmar forces). But the victory for the resistance has come at a cost.

Rihkhawdar has turned into a ghost town with abandoned government offices and locked civilian homes, with flowerpots left to dry in the cold. A few families have returned from the Indian side of the border and kept their doors open to visitors.

The population of Rihkhawdar and Khawmawi together is estimated to be a little over 6,000. Both places looked unusually quiet during this correspondent’s visit on 28 November.

There was a surreal atmosphere at the demolished camps — the Rih camp or the company headquarters of the Myanmar military at Ward No. 1 of Rihkhawdar, and the Tiau camp at Ward No. 2 near Khawmawi. The Rih camp, situated near the Rih Dil lake, is just about two miles from Zokhawthar in Mizoram, or a five-minute Kenbo bike-ride to the town.

Northwest Myanmar has remained a remote and largely undeveloped region, particularly in the mountainous area bordering India and Bangladesh, which is home to several ethnic groups. Since the early 1990s, the military junta has sought to establish greater control over this region — building roads and establishing military bases and outposts. The army wanted to not only quell simmering ethnic insurgencies, but also expand its trade links with India.

Pastor Lalsawichuanga believed that by the end of next year, the PDFs will “rule over Chin State”.

“The civilians and PDFs together fight for Myanmar. And if the PDFs hold victory, we will live in freedom. Natural resources are all under control of the military junta and not used for people. We will live with it and become rich once our goal is achieved,” he said.

A narrow route through dense undergrowth led to the once well-fortified Tiau camp near Khawmawi. Along the way, one could see the impact of aerial bombings on ground — a crater near a camp, and a damaged cemetery.

Everything around the camp resonated with iconic features of the First World War and guerilla warfare tactics — sandbag bunkers, barbed wire and booby traps, perimeter barriers using tin cans on wired fences to sound alert against raiders.

One of these abandoned camps had remnants of fresh garden produce — sweet potatoes dug out during the demolition, ash gourds in a ransacked storeroom, a blue plastic pitcher and some dry ingredients on the kitchen table besides a teacup. The soldiers must have wasted no time to get away — a Chin fighter at the site pointed towards an opening in the wired fence used by the military to escape.

About 45 Myanmar army personnel had found their way into India when the camps were attacked. They surrendered to Mizoram police on 13 November and were later handed over to the paramilitary force of Assam Rifles, further enabling their repatriation to Myanmar.

Green helmets and armour plates near the bunkers and trenches, a torn bag of rice and a shirt that was part of a soldier’s uniform made for haunting pictures at the overrun camps. A few unexploded drone bombs lay in sight.

“For this particular operation, every force got themselves ready — in group, and also individually. Since 10 November, we started planning. We had faced such missions before and gathered experience from that. According to plan, we set off on the evening of 12 November, and planned to capture the junta camp by 9 am. But we took time and were able to capture it by 5 pm. We were delayed because the junta used different tactics to deter us,” said a Chin soldier who was part of the mission.

“We avoided collateral damage on the battlefield. According to regulations, we cannot give prior information to the civilians, but try our best to protect them when the war is on — in any possible way we can,” he added.

A guerrilla fighter standing guard at the Tiau camp navigated through possible land mines planted along a passage as others trailed behind. A short distance ahead, one could see a small cavity triggered by a mine explosion, in which a villager reportedly lost his toes.

The number of casualties in the recent assault could not be independently verified, but a Myanmar army soldier killed in action was supposedly buried at the camp by the Rih lake.

At this camp of the 268 Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) of the Myanmar army, the Chin national flag fluttered under the blue sky. The captured Rih military camp was said to be “more than 50 years old”.

“As we have captured their camp, it is expected of the junta to come for us. But, we are ever ready to protect our land and hold the position. Though they might come again, it is impossible to reoccupy the camp because we have dismantled it completely,” said the Chin soldier.

Chin residents call for unity of CDFs

While the frontline Chin guerrillas are gaining combat experience with every victory, the civilian population raised concerned about the differences between different ethnic armed organisations in Chin State.

The CDF fighters are also members of the umbrella union, the Chinland Joint Defense Committee (CJDC) that was formed months after the coup — to lay down protocols, and mediate between the groups for any misunderstanding or conflict. It comprises representatives from the nine townships of Chin state and different small tribes. In past months, there have been incidents of disagreement between some of the groups, at times attributed to “lack of coordination” on ground.

When this correspondent visited the Chin National Defence Force (CNDF) camp in Falam in January, it was learned that though the groups have a common objective of Chin nation building, the method of achieving the goal is different. The CNDF is the armed wing of the Chin National Organisation (CNO), formed on 13 April, 2021.

“To maintain unity, they must have good training…They should be obedient and not indulge in any illegal activity. The chief leaders from different CDFs must have close relationships with each other and help one another…Then we will all have unity,” said pastor Lalsawichuanga.

Meanwhile, another Rihkhawdar resident quoted earlier, Vanluaia, said that the local residents have pledged their support for the CDFs to continue their fight against the military regime.

“Till date, the resistance fighters are good to us, and friendly too. But we don’t know about the future. We dare not expect much from them because the Spring Revolution is still on. The only thing we can do is give our support,” he said.

Lalsawichuanga hoped that the people of Chin State always remain united. “…We hope that the victory run continues…After we get freedom, the Chin State, the NUG might draft a separate constitution, but I hope Chin State will always remain Chin State, and all tribes will live united. Right to self-determination should prevail.”

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)

Also Read: Delays, security challenges — how turmoil in Myanmar is holding back India’s ‘Act East Policy’