A vegetable vendor operating in Delhi’s Navjivan Vihar said he and two others were forcibly evicted from the posh colony in March by the local resident welfare association (RWA). They were finally allowed in September, months into Unlock, but only after they had approached police for help.

In March, just as the Covid-19 lockdown kicked in, there were multiple reports of doctors being harassed and threatened with eviction by neighbours, landlords and RWAs. The doctors formed the frontlines of the battle against Covid-19 and they were seen as a transmission threat. Similar experiences awaited airline crew members engaged in bringing back Indians stranded abroad during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, even forcing Air India to issue a statement lashing out at RWAs.

Reports from some residential societies in the NCR suburbs of Gurgaon and Noida claim domestic workers were forbidden from using lifts, an order believed to be aimed at curbing Covid transmission risk. While a society in Gurgaon allegedly asked employers to pick up and drop their domestic workers in the lobby, so the latter wouldn’t operate lifts, another in Noida barred elevator use altogether, forcing them to climb up multiple flights of stairs.

Last month, in Bengaluru’s techie hub Whitefield, an RWA for an apartment complex issued a circular saying police had asked all societies to turn in information on residents, “especially” bachelors/spinsters staying on rent or residing alone. According to the circular, which came amid an ongoing probe into an alleged drug racket in the city, the request came after police “found bachelors staying in rented apartments in other societies involved in storing narcotics/drugs”. The details sought included “name, contact number and flat number of the bachelor/spinster staying in your apartment”, “vehicle number of bachelors/spinsters, if they are incoming or going late night”, and “suspicious activities (like late-night parties). ThePrint subsequently learnt from police that the notice was fake. Whitefield Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) said they had initiated action against the society for spreading false information. Police, he added, had asked RWAs to be alert, “but this is not what we meant”.

RWAs, or colony-, apartment- and area-wise management bodies elected by residents, have become a mainstay of Indian metropolises, from Delhi-NCR to Bengaluru.

As more and more gated colonies, societies and apartment complexes come up in cities, creating mini-communities that see themselves as guarded against the outside world, RWAs play an important role, raising local issues with the administration and managing security-related concerns within their limits.

In challenging times like the Covid-19 pandemic, these associations are crucial to the implementation of government campaigns on the ground.

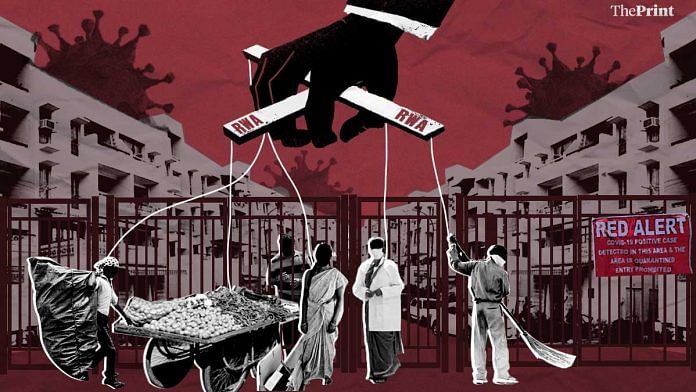

But, ever so often, they hit the headlines with diktats that appear to be driven by personal bias and whims and have little to do with the law.

Several RWAs, for example, have been known to bar bachelors as tenants, as well as pet ownership. Amid Covid-19, many of the RWAs in Delhi and NCR have continued to impose rules blocking the entry of domestic workers and vendors — or imposing controversial conditions if they are allowed — long after the government eased lockdown norms in this regard.

RWAs have justified some of their controversial restrictions through the Covid-19 pandemic as measures necessary for the safety of the residents. But complaints about their conduct persist, with many describing it as dictatorial and unilateral.

Also Read: In coronavirus crisis, are RWAs helping or becoming vigilantes?

How the RWA came to be

RWAs are not official organs of the government.

RWAs are voluntary organisations formed under the Societies Registration Act, 1860. While they have no statutory powers, they are governed by a Memorandum of Association that outlines their goals and functions. They are recognised as legal persons who can sue and be sued for their actions. They cannot, however, make rules and regulations contrary to the law.

“RWAs are the result of urbanisation. The co-operative housing movement of the 1970s paved way for RWAs to play a bigger role in urban governance,” said Sanjay Srivastava, professor of sociology at the Institute of Economic Growth.

“In the 1950s and the 1960s, governments were building cities and were seen as capable of taking care of their needs. But this changed in the later decades,” he added.

The demand for housing co-operatives rose as cities expanded. In 1969, this trend resulted in the formation of the National Cooperative Housing Federation (NCHF) of India, the apex organisation promoting and facilitating the function of cooperative housing societies.

RWAs emerged from this movement too. Although both exist to oversee the welfare of residents, housing cooperatives and RWAs are distinct in their constitution. Housing cooperatives are often found in older neighbourhoods, where one of the key purposes is to build and maintain the property. They are governed by specific bylaws under different states’ cooperative society Acts and cooperative societies rules.

RWAs, meanwhile, were born out of the need for efficient supply of civic amenities, and often act as interlocutors between government authorities and private individuals. If residents feel vehicles routinely speed through their lane, endangering pedestrians, RWAs can approach the government to get speed-breakers made on the road.

Among other things, they appoint guards for gates around a colony to restrict entry, to address resident concerns about safety.

They are registered under the Society Registration Act — a law overseeing societies involved in public good — but experts told ThePrint that there are largely no bylaws to govern their functioning.

Amid the Covid-19 crisis, RWAs have helped keep residents informed about cases in the vicinity through social media groups.

They have also emerged as aides of the government to keep violations of pandemic guidelines in check.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has put out a spate of advisories and guidelines for RWAs to follow in light of the pandemic, recommending visitors be screened at the entrance of gated colonies and social distance be maintained on the premises, among others.

In July, ThePrint reported that the government is putting together an ambitious Rs 7,000 crore plan for urban health and wellness centres (HWCs), with a pivotal role envisaged for RWAs.

Tasked with the duty of aiding the government’s efforts to check the pandemic, many RWAs across the country have banded together to form temporary quarantine centres, counselled Covid-positive residents, and even aided local governments with testing.

However, there have been instances of overreach and discrimination.

Upender Kaul, a Delhi-based cardiologist, sued his RWA in the Greater Kailash-I area when they closed six of the colony’s seven gates during the lockdown as a “protective measure”, and refused to entertain his requests for relief. The only gate open was a kilometre from Kaul’s house, creating a problem for his elderly father, who walks to a nearby temple beyond the gates.

“I called them, wrote to them, set up meetings with them. Nothing worked. The only way to get them to open the gate was to sue them, so I did,” Kaul said. “They did this to keep coronavirus away, but it was just a huge inconvenience with no scientific backing.”

The RWAs, however, defend themselves against such allegations.

“We cannot impose our wishes on everyone. That’s not how it works,” said Vimal Sharma, head of a group of RWAs in Noida.

When the lockdown came into force, no one was allowed into Sector 50, Noida, for 45 days. When restrictions began to be lifted, colony-wide WhatsApp groups decided who would be allowed to enter and how the gates would be guarded.

“Gates are kept closed keeping everyone’s wishes in mind. There are a few people who create issues. But the RWA will listen to the majority. A problem is worth solving if the majority within the colony is facing it,” Sharma added.

South Delhi District Magistrate B.M. Mishra said he hadn’t received any complaints about RWAs. “In fact, they are very co-operative. We share WhatsApp groups with them, and there are open channels of communication,” he added. Asked what the procedure was if a complaint did arise, or if RWAs kept gates closed without adequate permissions, Mishra said, “This is a hypothetical situation which hasn’t come up yet. We will address it if and when it does.”

Raja Puri, a businessman and secretary of the Greater Kailash-1 or GK-1 society where Kaul lives, told ThePrint, “I don’t agree when people say RWAs are unreasonable. Our blocks are often trespassed by outsiders, so the gates were kept closed. We make these rules with a healthy consensus.”

This consensus doesn’t, however, always include those outside the colony. A study by Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), a Delhi-based research and training institute, across seven cities found that, “RWAs accepted that they do not have meaningful linkages with the poor areas and residents in their locality, even though dependence on neighbourhood slums for day-to -day convenience was high.”

Srivastava said, “By living in gated spaces, people want to make a distinction between themselves and those who live outside. It signifies that those living within the gate are of a certain economic stature. The pandemic has exacerbated this.”

Dalia Chakraborty, a professor of sociology at Jadavpur University, said of Kolkata colonies that there were restrictions on vegetable vendors and other lower income groups until August. “Maids were allowed initially because the middle class depends on them so heavily,” she said.

The same divides have played out in the posh areas of Bengaluru like Indiranagar and Koramangala, but not as “extremely” as in Delhi, said Mathew Idiculla, a lawyer and urban researcher based in the Karnataka capital.

Talking about the concept of RWAs, Idiculla said a natural fallout of cities expanding is the movement of people from more “public” neighbourhoods to those that are more “private”.

“There is a larger system of private provision in more private neighbourhoods. These societies have, in a way, seceded from the state because they don’t rely on public services as much,” he explained. “In these neighbourhoods, RWAs become the de-facto authorities who manage the space.”

Also Read: Media rumours and vicious RWAs have been worst for animals during Covid: Maneka Gandhi

Different cities, different experiences

Different cities, however, don’t always have the exact same experience with the RWAs. Delhi, for one, is believed to have a stronger, more powerful, role for RWAs, than any other metropolitan city.

This can be attributed to factors such as security concerns in the aftermath of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, which led to riots, and the increase in the number of Delhi Development Authority flats, which mandated a management body.

However, it is the Delhi government’s Bhagidari scheme, enacted by the then Sheila Dikshit government in 1998 to resolve civic issues through collaborative participation, that is credited with propelling RWAs into the centre of urban governance.

Monthly meetings and workshops were held with RWAs to discuss civic issues and problems, which were resolved through discussion.

For years, the biggest criticism the scheme received was that it catered to middle class neighbourhoods, and ignored poorer ones, giving certain colonies more bargaining power than others.

According to Srivastava, while the Bhagidari scheme did give RWAs more negotiating power, there were other factors that facilitated their rise.

“With Delhi expanding and more migrants coming in, there was also this need to stay ‘protected’ from an urban threat, and an increasing notion of self-sufficiency that has driven several of the RWAs to exclusivity,” he said.

Mumbai, meanwhile, has a history of forming strong cooperatives, particularly for its famous mills. Housing settlements have taken the shape of apartment complexes that are presided over largely by housing cooperative societies. Where RWAs do exist, their powers are curbed by the stringent provisions under the Maharashtra Cooperative Societies Act.

“Unlike other states, we have the Maharashtra societies Act, which ensures housing societies are governed by bylaws that they can’t overstep. RWAs don’t interfere with daily management because of this,” said Rajeev Saxena, chairman of a taskforce under the Maharashtra Societies Welfare Association or MahaseWA, a non-profit that assists cooperative societies.

“In other states, RWAs are largely unstructured and there’s no uniformity when it comes to their roles and responsibilities, so their activities may go under the radar,” he added.

In Kolkata, experts say, RWAs have typically played a less interfering role in the lives of residents and non-residents.

Chakraborty, the Jadavpur University professor, said the coronavirus pandemic was the first time there were major impositions on movement from poorer neighbourhoods to more wealthy ones.

“There is a boundary and a class difference, but before the pandemic there was a continuous flow of people moving in and going out of (wealthier colonies). For the first time there was a complete restriction,” she said.

A minister in the Bengal government said there were sporadic instances of RWAs being uncooperative, but they were swiftly dealt with by police.

Also Read: RWAs acting like the first line of defence against coronavirus. They are Modi’s soldiers

‘RWAs need to be more democratic’

The power RWAs exert over their gates in Delhi is “astonishing” because “the growth of the city has facilitated it”, said Idiculla.

“Affluent RWAs have public servants and police on their WhatsApp groups, making them privy to these decisions,” he added.

Lawyer B.L. Wali, who practices in the Delhi High Court and fought Kaul’s case, said this is also why RWAs “open and close gates with impunity, as well as create arbitrary rules without retribution”.

“It took a court case to open one gate in one neighbourhood. No one has the energy to do it, so most people will comply with their rules even if they cause an inconvenience,” he added.

“Unless RWAs are better structured and regulated, overreach and restrictions will become more and more common,” Wali told ThePrint. “Where there are conflicts, RWAs need to be more democratic and hear what residents have to say, instead of imposing their own decisions. That’s another way this can be helped.”

Inputs from Rohini Swamy and Madhuparna Das

This report has been updated to correct an error in the spelling of lawyer and urban researcher Mathew Idiculla’s name

Also Read: Pseudo parents or modern Khaps, Indian RWAs are here to police young, single people

In Rajnagar extension, Ghaziabad RWA’s have gone ahead giving permission for pandals violating COVID precautions. Residents including guards and people working in the society don’t follow the guidelines. There is no policy according to government guidelines which has to be implemented.

This is a timely and well written piece. It is imperative, Model bye laws should be laid down to narrow the scope for disagreement on management of RWA’s. Clear stipulations on matters such as funding and elections with redressal in case management committee fails to adhere to these. Otherwise, it will remain the Wild West. Personal relations with family and friends in your colony are often at stake and this allows some committees to push the limits of their authority. Builders also have a silent role in exchanging favours with some RWA Executive Bodies.

TS Darbari – The management or actions taken to stop crime or spread of coronavirus is good; however, if they go to the extent of interfering in the personal life of any person or become harassment for others, they should be stopped. We have seen numerous examples during this COVID19 when people were harassed unknowingly because of a fear of spread of COVID which is not good. We must understand the plight of the people who have to undergo tremendous pain and agony during such actions taken by the elected bodies to provide safety to its citizens. #TS_Darbari #Ts_Darbari_Blog #TS_Darbari_News #Ts_Darbari_Views #Ts_Darbari_Blogger #TS_Darbari_Comments #Ts_Darbari_Opinion #About_TS_Darbari #TS_Darbari_Articles #Politics #Views #Comments Mr. TS Darbari is a top management professional, with several years of rich & diversified experience in Corporate Strategy, New Business Development, Sales & Marketing, Commercial Operations, Project Management, Financial Management and Strategic Alliances