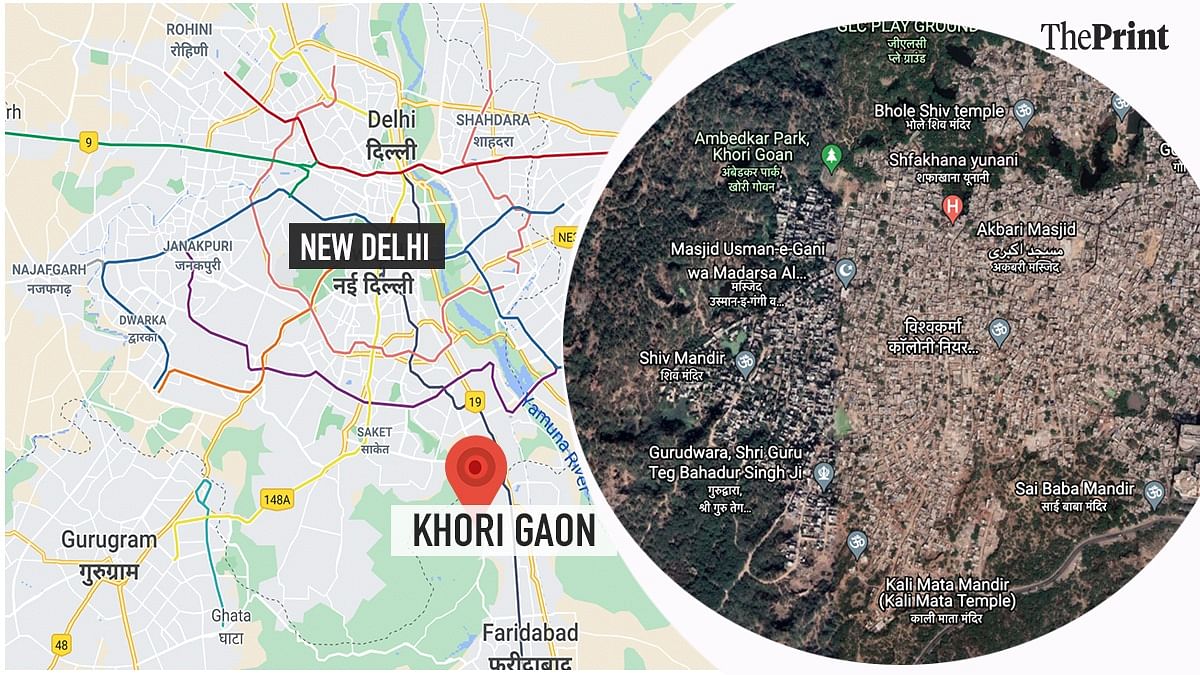

Khori (Faridabad): Faridabad’s Khori village, a colony of encroached settlements in the Aravalli forests, looks like it was in the path of a storm. Bricks from demolished houses lie scattered all over, punctuated with toys, torn books, broken TVs and shards of glass. Crushed two-wheelers peek out of the rubble, and families are seen trawling the debris to collect what can be salvaged.

The Municipal Corporation of Faridabad (MCF) is razing thousands of homes in Khori Gaon following a 7 June Supreme Court order setting a six-week deadline for the encroachments to be cleared.

There is no clarity on the exact number of homes in this settlement, which primarily comprises migrant workers.

According to the district administration, a drone survey revealed there were 5,100 homes in the area. However, a PIL filed in the Supreme Court by one of the residents puts the number at 10,000.

The narrative surrounding the Khori village follows two divergent themes. To the Supreme Court and the district administration, the residents are encroachers on government land comprising sensitive forests. They have been trying to demolish the encroachments for nearly a decade, but the residents are putting up a fight.

The residents plead innocence, and claim they were taken for a ride by a mafia which took money from them and “sold” them the land using fake documents.

They accuse the police of being hand in glove with the alleged mafia, and have laid down two conditions for moving out: Rehabilitation and the arrest of those who allegedly duped them.

Haryana Police doesn’t discount the residents’ allegations. They say an investigation is under way into their accusations, but point out that the residents ought to have filed a complaint with police in the matter.

Meanwhile, the situation in Khori remains tense. In light of protests by residents, the district administration imposed Section 144 of CrPC — barring assembly — in the village on 14 June.

Two days earlier, 12 people were arrested for organising a protest at Surajkund and attempting to block traffic. They’ve been booked under sections 114 (joining unlawful assembly with deadly weapon), 147 (rioting), 149 (offence in prosecution of common objective), 186 (obstructing public officials from discharging duties), 188 (disobedience of public servant), 269 (spreading contagious disease), 285 (endangerment of human life), and 341 (wrongful restraint) of the IPC.

On its part, the Haryana government has said it is discussing resettlement options, but only for those who belong to the state. However, the policy under which they are likely to be rehabilitated has been challenged in court by the residents, who say its cut-off date of 2003 would leave most of them out in the cold.

The case will come up for hearing on 27 July, along with other pending petitions dealing with the issue of rehabilitation.

Also Read: Delhi Ridge: How it went from a colonial forest to murder scene to morning-walk garden

An ecologically sensitive zone

The Aravallis, which run along Gujarat, Rajasthan, Delhi and Haryana, constitute a fragile ecological zone. Considered to be among the oldest mountain ranges in the world, it is rich in minerals, which has made it a prime site for mining.

The range is crucial for groundwater recharge, and is seen as the “green lungs” of pollution-choked Delhi-NCR. It’s also considered the last barrier preventing the western desert from expanding into the Gangetic grain bowl of Uttar Pradesh.

A set of orders passed by the Supreme Court over the years have granted the range protection from mining, but illegal encroachments, constructions, as well as mining remain a constant problem.

The overexploitation of this range has manifested itself in local ecological changes of concern.

Khori is located in the lap of the Aravalli hills, where a quarry once stood. All mining activities in the Aravalli hill areas of Faridabad, Gurugram and Mewat were barred in 2009 on court orders.

The settlements in Khori date back to the 1990s. It initially housed workers of the quarry, but later expanded as more residents came in.

Speaking to ThePrint, architect Ishita Chatterjee, a PhD Scholar at the University of Melbourne who has been studying Khori Gaon, said the settlers are mainly migrants from Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, West Bengal and Bihar.

“In the early 2000s, many people living in Delhi’s bastis that had gotten demolished, were congested, or where rent was proving to be expensive, moved to the city’s periphery,” she said. “Additionally, workers in quarries work in debt bondage so even when the quarry was shut people couldn’t leave.”

When it came under the scanner

When mining was banned in the region, the area where Khori is situated came under the protection of the Punjab Land Preservation Act (PLPA, which dates back before Punjab’s split, and now applies to Haryana too).

According to the law, no construction is allowed in the area without permission from the central government under the Forest Conservation Act.

Since it’s an illegal settlement, Khori has faced demolition at the hands of the MCF multiple times over the years, said Anuprada Singh, an advocate with the Human Rights Law Network who is currently working on the case on behalf of the residents.

“Multiple demolitions have taken place over the years. Sometimes 100-300 houses were demolished, other times only 7-8,” she added.

The case first reached the judiciary in 2010, when a group called the Khori Gaon Welfare Association moved the Punjab and Haryana High Court against the demolition exercise. In 2012, another resident group, called the Khori Gaon Colony Kalyan Samiti, filed a writ petition in the Punjab and Haryana High Court seeking regularisation of their homes, or, alternatively, rehabilitation. The high court pronounced its verdict for both petitions in 2016.

“In 2016, the Punjab and Haryana High Court directed the Haryana government to decide the slum dwellers’ fate and their rehabilitation. In the same judgment, the court directed the Government of India to form a nationwide policy on the right to housing,” she added.

It emerged during the course of the trial that 4 out of 10 encroachments in the area had taken place only after 2010, and so many of the encroachers were not eligible for rehabilitation under the Haryana Shehri Vikas Pradhikaran Rehabilitation Policy, which sets 1.4.2003 as the cut-off date.

In 2017, the MCF moved the Supreme Court against the 2016 high court judgment. It argued that the villagers in Khori are encroachers and thus not eligible for rehabilitation.

On 19 February 2020, the Supreme Court passed its first order in the case, calling for the removal of all encroachers from forest land. Following this order, 1,700 houses were demolished in September 2020, Anuprada Singh said.

In January 2021, a PIL was filed by advocate Colin Gonsalves, representing five residents, in the Supreme Court challenging the cut-off date for rehabilitation under the Haryana Shehri Vikas Pradhikaran Rehabilitation Policy, under which the residents expect to be rehabilitated.

Gonsalves requested that the cut-off date be forwarded to 2015 from 2003, so more residents can be eligible.

The demolition order was reiterated by the court in April and June. As it set the six-week deadline, the Supreme Court rejected petitions moved by residents to stay the demolition drive unless the question of their rehabilitation by the government was settled.

The Supreme Court has taken a stringent view of the demolition exercise, and asked the authorities for a compliance report. It has described the residents as land-grabbers, and rejected the lawyers’ request for a lenient view, saying they had had time since last February to apply for rehabilitation.

The court will take up the request for extending the cut-off date on 27 July.

Nirmal Gorana, a housing rights activist who has been working in Khori village for the last 5 years, questioned the need to evict the villagers.

“Adivasis or villagers aren’t causing damage to the forest. In fact, they’re guarding the Aravallis against illegal mining. What forests will you save by demolishing houses here? This land will be barren, unsuitable for any tree plantation. This is just exploitation of the poor to make way for the rich,” he added.

Also Read: Five hidden benefits of forests everyone should know

‘Duped by mafia’

As of last week, the district administration claimed, 50 per cent of the houses had already been vacated, while the MCF said they will follow the Supreme Court order fully.

Their homes may have been demolished but the residents have dug their heels in. Left homeless amid a pandemic, they want assured rehabilitation and punishment for those who duped them.

A 70-year-old resident named Ganeshi Lal allegedly committed suicide after the Supreme Court order, and villagers warn more such cases could follow if they aren’t rehabilitated by the Haryana government.

Ghanshyam Paderam, who claimed to have been living at Khori for more than a decade, said he finds himself at sea.

“I bought this land for Rs 3 lakh and built the foundation of this house with my own hands. This house is my entire life’s savings. It’s the only home I’ve ever known. Please tell me why I should leave, and if I leave, where do I go?” added Paderam, who worked in the hospitality industry earlier but is currently unemployed.

As an illegal colony, Khori never got electricity and water from the government. Residents allegedly pilfered power off the supply for Delhi, and arranged tankers for water requirements.

In the wake of the Supreme Court order, the power supply has been disconnected, and residents allege tankers are being prevented from entering by police.

“Modi ji says ‘stay inside the house’. But now the government wants us to leave the shelter of the only roof we’ve ever known. Are we not at risk of dying from Covid now?” said a woman who didn’t wish to be named. “Modi ji also talks about Swachh Bharat, but by cutting our water supply, the state is forcing us to defecate out in the open. In this heat, I have to count my sips.”

Without the promise of alternative housing, the residents say they’d rather die than leave.

“These judges in the Supreme Court have never visited us. They’re sitting far from reality in their AC rooms passing orders. I want to tell them, if you want us to move, at least give us an alternative place to stay,” said Jeetendra Vishkarma, a daily wage worker who does welding work.

“If not, they may throw atom bombs here and we won’t move, we’ll poison our kids and then die here with our houses,” he added.

Vishkarma alleged the authorities had colluded in the dubious land deals that landed them in this situation.

“The forest departments, police, and the government have all earned money by the dubious land they sold us. Let the rest of the world see as residents of Khori are murdered,” he added.

Anuradha said “this place was under the heavy influence of land mafia”.

“People were using fake power of attorneys to sell land to the villagers. The settlers here are mostly poor and this land was offered to them at cheaper rates, in easy instalments and at lower rate of interests. So, they bought it. They also have ration cards and voter ID cards on these addresses,” she added.

Police say they’re trying to find out who sold this government land to the villagers.

“Local residents here indeed bought land at Rs 1,000 per square metre. The dealers provided them with kaccha bills and fake land deeds. We’re looking at various dealers who were running this racket all this time,” said Faridabad Police Public Relations Officer (PRO) Sube Singh.

NIT Faridabad Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) Anshu Singla refused to share any operational details of the investigation.

“All I can say is we’re investigating people in the matter and will soon be taking strict action against them and filing FIRs,” he said.

Asked about villagers’ accusations about collusion between mafia and police personnel, Singh said, “I am not saying that every policeman would’ve been honest or their accusations are false. However, if they (the villagers) were facing such corruption at the hands of the police, they should file a complaint with us. No such complaint has been registered by them so far,” PRO Singh added.

About the unchecked proliferation of the colony, he said, “If you ask me, this is a total failure of the Municipal Corporation of Faridabad.”

When ThePrint visited MCF commissioner Garima Mittal at her office in Faridabad, she said she has “only and only one thing to say about Khori village”.

“I will implement the Supreme Court order in its full spirit. That’s all I have to say no matter what you ask me,” she said.

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Everything should be done to ensure protection of forests, animal habitats, says PM Modi