New Delhi: Karnataka has seen the steepest fall in sex ratio at birth (SRB) among big states in the past 10 years while Punjab has improved the most on this front, according to an analysis of the latest Sample Registration System (SRS) data by ThePrint.

The southern state saw its SRB — number of boys born alive per 100 girls born alive — come down from 944 in 2008-10 (three-year average) to 916 in 2018-20, which translates to 28 less female births for every 1,000 male births than what the state reported a decade ago.

Other states that recorded a significant fall in SRB are Gujarat, with 27 fewer female births, followed by Bihar (22), Chhattisgarh (22), Delhi (22) and Maharashtra (20).

The northern states — often perceived as being more patriarchal — have shown a marked improvement. With an SRB of 897 in 2018-20, Punjab leads the list with 61 more female births per 1,000 male births than it did in 2008-10 (836). Jammu Kashmir (51), Rajasthan (36), Uttar Pradesh (31) and Haryana (21) were other states that improved on this indicator.

Overall, India has seen a marginal improvement over the past decade — from 905 in 2008-10 to 907 in 2018-20.

Experts take data with pinch of salt

While the numbers are alarming for the southern state, experts assert that Karnataka’s data, or for that matter a drastic change in numbers for any other state, have to be taken with a pinch of salt.

“The SRS used the population metrics using the 2001 frame till 2013 and the 2011 Census after that period. Why this matters is because this defines the boundaries of urban versus rural areas. Our research showed that increasing urban class size corresponded to a higher preference for sons, implying bigger cities having a skewed SRB, hence, the SRB deterioration. So far, we know that rural areas generally have better sex ratio than urban areas. Preference for small family size in urban areas with at least one son may be one of the factors behind declining sex ratio at birth,” Debolina Kundu of Delhi-based National Institute of Urban Affairs told ThePrint.

The root cause behind extreme effects in SRB builds the case for more detailed qualitative and quantitative research, she said.

“In the past two decades, Karnataka has seen a mass migration of youngsters coming from northern parts of the country. As they move in search of better opportunities, the culture of strong preference for sons also travels with them,” Kundu said, adding that the role of migration in Karnataka’s declining sex ratio needs more research.

Conducted by the Registrar General of India, the 2020 SRS data covered over 8.4 million people. Unlike the Census or the National Family Health Survey — which map quality attributes such as income group, migration status or societal changes — the primary objective of the SRS survey is to calculate demographic indicators like fertility rates, birth and death rates.

“There could be statistical shocks, or changes in the sample population picked up for data collection — that question needs to be answered by the SRS. The difference between two different points of time may not provide a complete picture sans the confidence interval of the trends,” said Prof. Chander Shekhar, department of fertility studies, International Institute for Population Sciences.

“The SRS gives the data, but we need more quality attributes to understand why a state is moving in which direction. Whether it’s migrants who are pushing down Karnataka’s sex ratio at birth, or has there been a change in social systems within the natives, needs more than mere indicators. Both are visible on the ground, but only sophisticated research can reveal who is contributing how much in the trajectory,” Shekhar explained.

Also Read: It’s girls! Surprise in survey as north India improves in sex ratio at birth, south worsens

Urban India leading the change

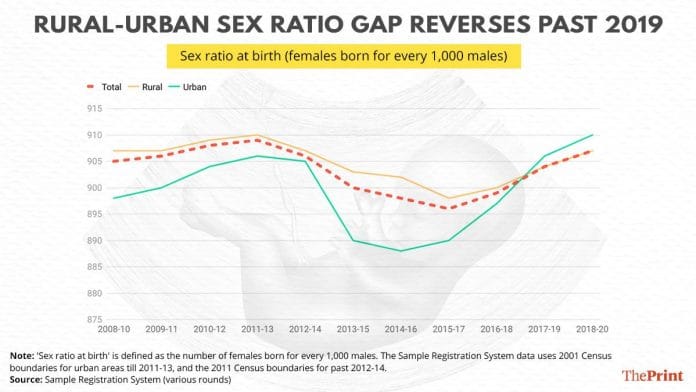

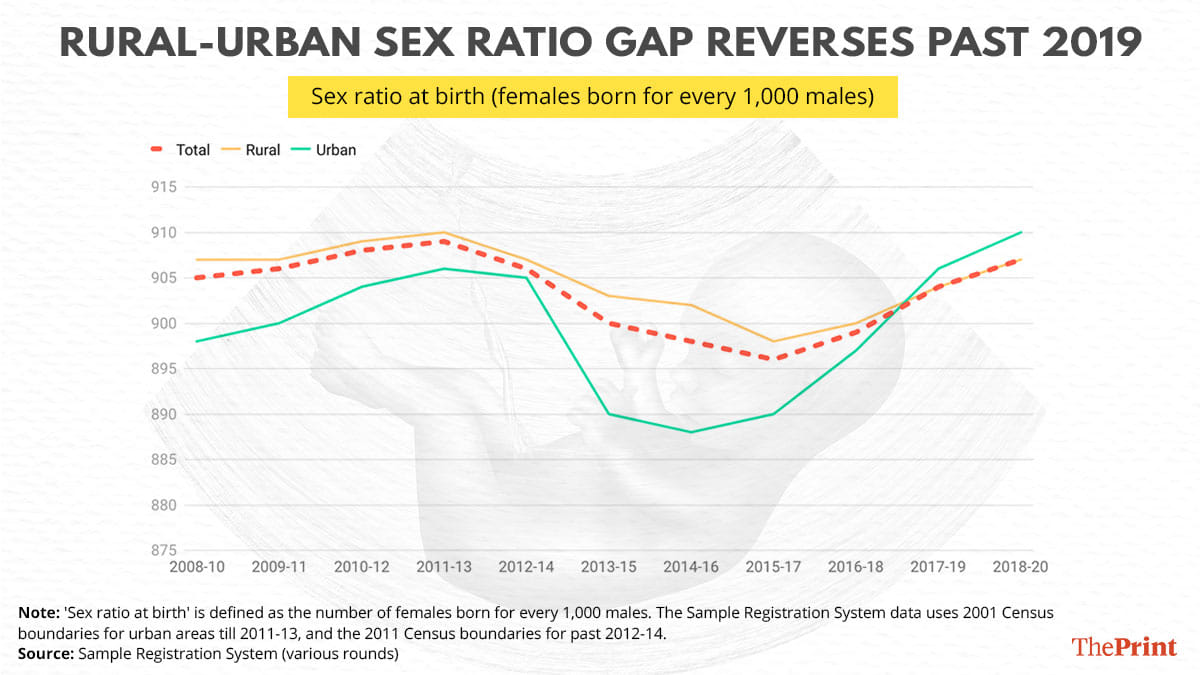

While SRS data is available separately for rural and urban areas, it shows that the trend in urban areas is defining India’s overall curve.

In 2008-10, urban India’s sex ratio at birth was 898 which rose to 906 by 2011-13. The ratio then fell in the succeeding years to settle at 888 by 2014-16. Since then, it has improved to outstrip rural India in the period of 2017-19.

The hinterland, too, had a similar trajectory, but the numbers did not disperse as wide as its urban counterparts.

In 2008-10, Karnataka’s urban sex ratio at birth was 934, which dropped to 871 in 2018-20. This means that on average, 63 fewer females were born per 1,000 males compared to a decade ago.

Even urban areas of lesser developed states like Bihar (897), Rajasthan (901), Odisha (907), Chhattisgarh (910) and Jharkhand (910), which were behind Karnataka 10 years ago, fared better than the southern state.

Overall, urban India saw the ratio rise from 898 to 910 in the same period.

Link between urbanisation & SRB

Is there a relationship between rising urbanisation and deterioration in sex ratio at birth? Yes, say Kundu and her peers.

In an article, ‘Sex Ratio at Birth in Urban India’, published in Economy and Political Weekly (EPW), the authors mentioned that urbanisation and sex ratio at birth were negatively related to each other.

“An exploration of the trends and patterns of sex ratio at birth in urban India and the processes behind son preference suggests a systematic worsening of SRB with increasing urban district size classes,” the article states.

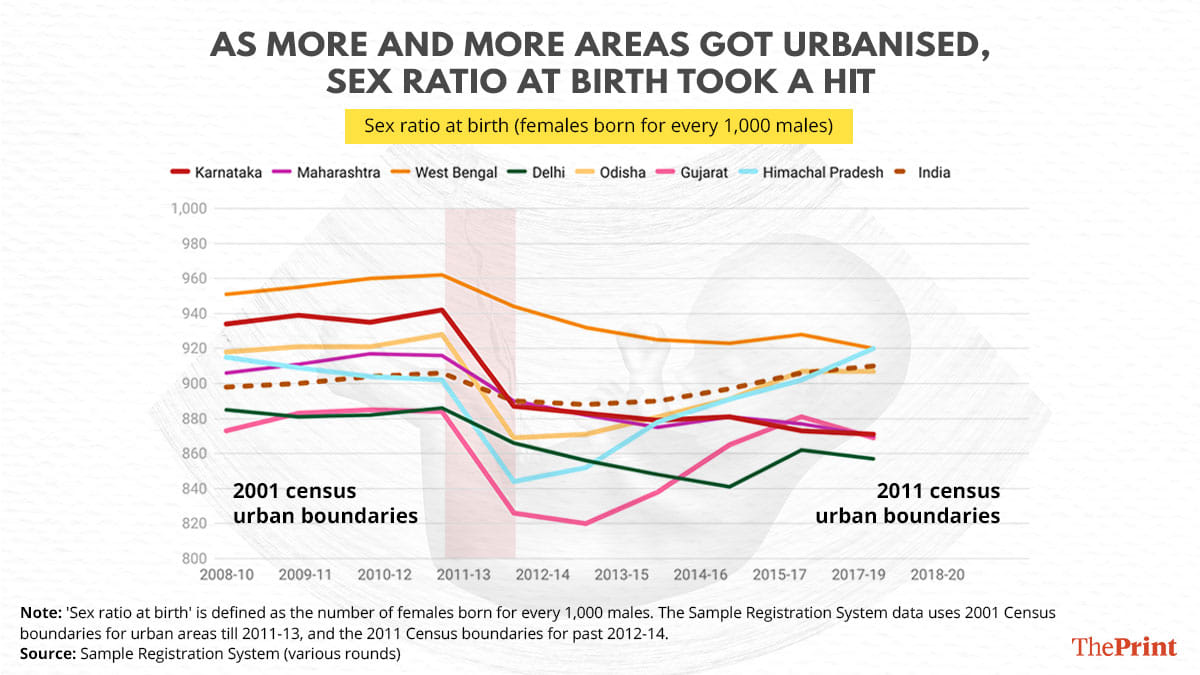

Until 2011-13, the Sample Registration System survey was using urban boundaries as mapped in the 2001 Census. As more and more villages urbanised and appeared in the 2011 Census, there was a drastic fall in the sex ratio at birth in several states, especially from 2012-14 onwards. In Karnataka’s case, the urban SRB plunged from 942 in 2011-13 to 887 in 2012-14.

The relationship between sex ratio at birth and urbanisation needs to be read in context with declining fertility, said Prof. R. Nagarajan of Department of Population and Development at Mumbai’s International Institute for Population Sciences.

“As fertility declined first in urban areas, the pressure to give birth to a son continued. Access to ultrasound sonography was easier in urban areas compared to rural areas in the 1990s and 2000s. So, the continued demand for son coupled with the easy accessibility/supply of ultrasound sonography led to the decline of sex ratio at birth initially in urban India,” he told ThePrint.

The reason for the improvement now lies in the rising acceptance of daughters in urban India, he said. “The acceptance is slowly emerging among the urban, richer and most educated classes. It means that the patriarchal norms among these groups are slowly declining. The gradual increase in acceptance of daughters reveals weakening of rigid patriarchal norms.”

The academic also credited the policy measures carried out by the government for the fall in discrimination towards girls.

“The government has taken several measures to reduce societal aversion towards daughters in the past two decades. Equal rights to parental property for boys and girls, protection of women from domestic violence, prevention of sexual harassment at workplace are among the many [measures],” he said, adding that the combined initiatives of the central and state governments are showing some results.

“But [it’s] still a long way to reach the level of around 950 female births per 1,000 male births,” he added.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: As PM’s ‘Mann ki Baat’ urges awareness, experts say malnutrition as much a food availability issue