New Delhi: Once infamous for female foeticide, Punjab and Haryana have come a long way in fixing their skewed sex ratio at birth, a study by American think tank Pew Research Center has found.

According to its report titled ‘India’s sex ratio at birth begin to normalise’, released Tuesday, the number of boys born for every 100 girls has come down in both states — to 111 (Punjab) and 112 (Haryana) in 2019-21 from around 127 (in both) in 2001.

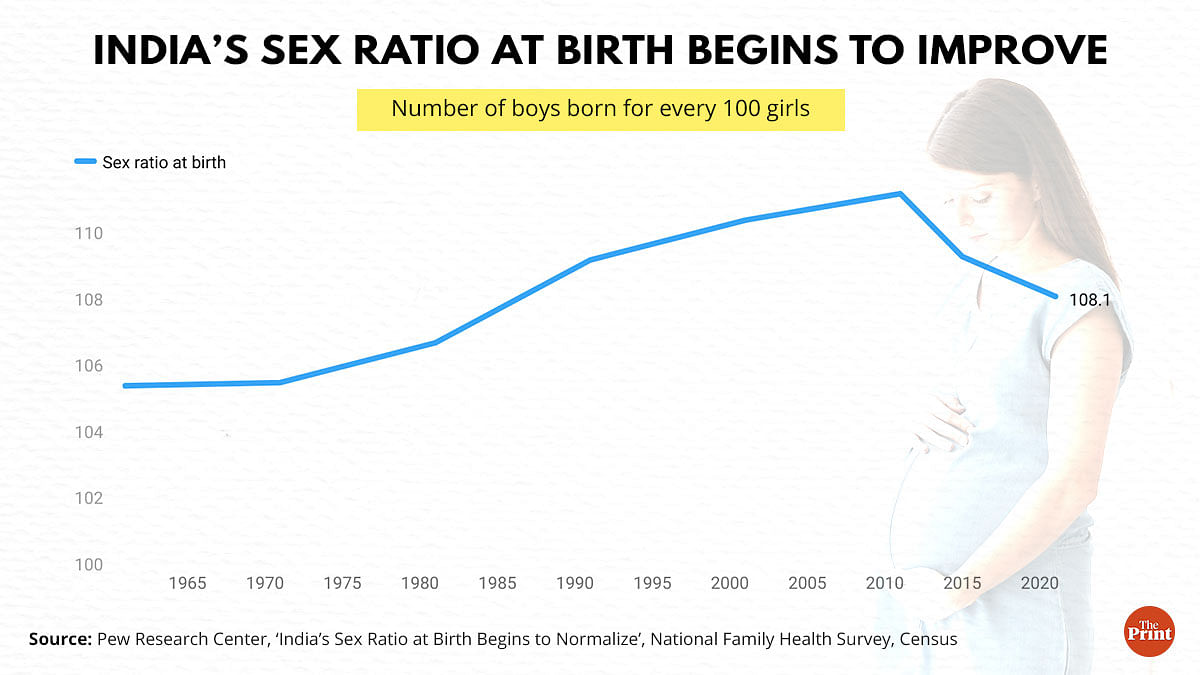

The report also shows that overall, India too has been able to narrow the gap; the number has gone down to 108 boys born for every 100 girls in 2019-21 from 110 in 2001.

Graphics: Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

The study uses data from five rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) updated until 2019-21, as well as India’s decadal census data until 2011.

Although the sex ratio at birth is defined in India in terms of the number of male births per 1,000 female births, the survey uses the international system, under which the ratio is expressed in terms of the number of males born for every 100 females.

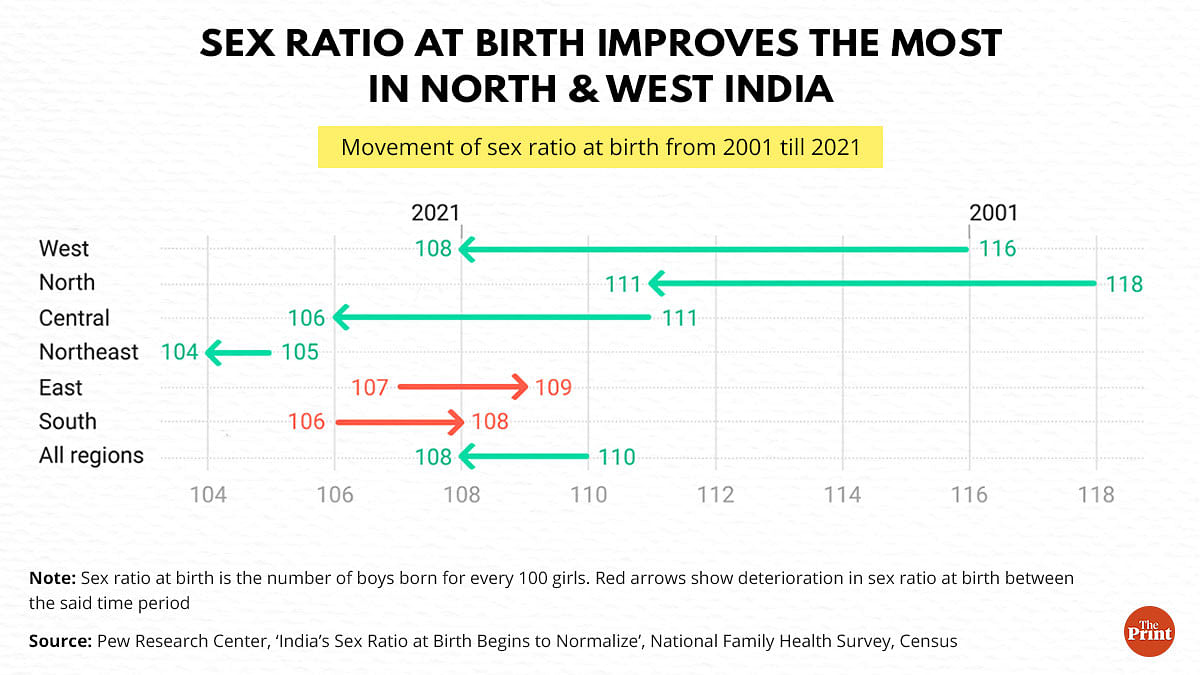

The report shows that the sex ratio at birth has seen the most improvement in the northern states of India, but deteriorated in the southern states, as well as in the east.

There has also been a notable decline in ‘son preference’ across India, particularly among Sikhs.

The report attributes the general improvement in sex ratio at birth to the Indian government’s efforts to curb sex selection — such as a ban on prenatal sex tests and sex-selective abortions as well as an advertisement campaign to save the girl child. These measures coincided with broader social changes in the country, such as wealth and education, it notes.

“The new data suggests that Indian families are becoming less likely to use abortion to ensure the birth of their sons rather than their daughters,” the study says.

Also Read: Delhi shows sharpest drop in sex ratio, govt calls out 4 states for ‘continuous decline’

South sees skew toward males

The study divides India into six zones based on geographical factors — north, east, west, south, central, and northeast.

The report shows that in the north — comprising Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, and the Union territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh — the sex ratio at birth has been narrowing, to an average of 111 boys for every 100 girls in 2019-21 from 118 boys in 2001.

On the other hand, the ratio widened in the five southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka — to 108 boys for every 100 girls in 2019-21 from 106 in 2001.

Graphics: Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

The sex ratio has also worsened in India’s eastern zone — Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Odisha — to 109 in 2019-21 from 107 in 2001.

In the rest of India, the sex ratio at birth has seen a general improvement, the study shows. In central India (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh), it has gone to 106 (boys per 100 girls) in 2019-21 from 111 in 2001, in the west (Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Goa), it went to 108 from 116.

In the northeast (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram, Tripura, and Sikkim), it improved marginally to 104 from 105.

“India’s southern and northeastern regions have consistently had sex ratios close to the natural balance, although the sex ratio in the south has recently started to skew toward males. In the relatively affluent south, the sex ratio at birth now is 108,” the report says.

Declining ‘son preference’

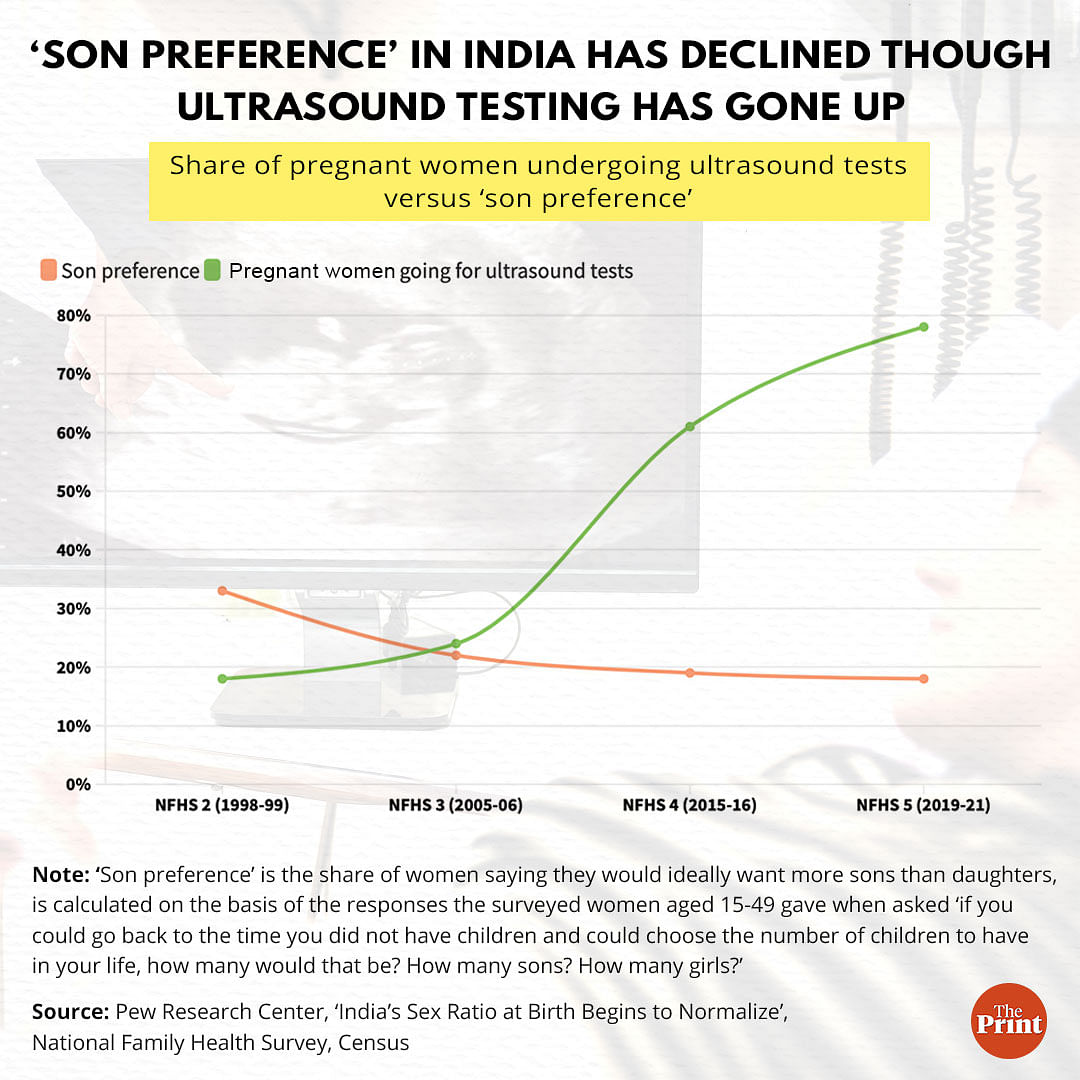

The authors also note a significant decline in ‘son preference’ — the desire to have more sons than daughters.

For this, the study uses NFHS surveys until 2019-21. The surveys asked women: “If you could go back to the time you did not have any children and could choose the number of children to have in your life, how many would that be? How many sons? How many girls?”. Based on their responses, the surveys provide an estimate of the number of women preferring sons over daughters.

According to the report, in 1998-99, one in every three women (33 per cent) wished they had more sons than daughters. This number, the report says, came down to 15 per cent in 2019-21.

Across religions, the steepest fall in ‘son preference’ was recorded among Sikhs — a community that, according to the study, had the most skewed sex ratio in the past (130 males per 100 females in 2001 as against the national average of 110).

Graphics: Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

In Sikhs, this metric dropped to just 9 per cent in 2019-21 from 30 per cent in 1998-99 — a fall by 21 per cent points.

This estimate has fallen by 19 per cent points (to 15 per cent from 34 per cent) among Hindus and by 15 per cent points (to 19 per cent from 34 per cent) among Muslims.

Among Christians, who had shown lower ‘son preference’ in the past, this metric has dropped to 12 per cent by 2019-21 from 20 per cent in 1998-99.

The report attributes the dramatic decline in ‘son preference’ among Sikhs to a shift in the attitude of upper-caste members of the community.

“Much of the movement in Sikhs’ sex ratio in recent decades can be attributed to upper-caste families — who are generally more educated, affluent, and likely to own land. The sex ratio among upper-caste Sikhs was far more skewed than among lower-caste Sikhs in the 1990s and early 2000s,” the report says.

“As upper-caste families account for about 40 per cent of all Sikhs, they play an important role in shaping Sikhs’ overall sex ratio at birth,” it adds.

Also Read: India struggles to meet gender equality goal second year in a row, ‘special attention’ needed

The case of the ‘missing’ girls

The study says that a decline in ‘son preference’ and stricter laws prohibiting pre-birth sex determination have brought about a general reduction in “missing” female births.

The report describes the “missing” births as an “estimate of how many more female births would have occurred during this time if there were no female-selective abortions”.

The report estimates that sex determination before birth has stopped more than 90 lakh girls from being born in the last two decades, although it reports a general decline in this trend in the last decade. It states that India’s annual average of “missing” female births due to sex-selective abortions came down to 4.1 lakh by 2019 from 4.8 lakh in 2010.

What makes this improvement significant, according to the report, is that this came about despite an uptick in the number of women opting for ultrasound tests.

Graphics: Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

India legalised abortion in 1971 and by the 1980s, prenatal ultrasounds became available.

An ultrasound, also known as sonography, is an imaging test used to look at the internal parts of the human body. It’s also a prenatal test used to diagnose the health and development of a foetus in the uterus. It’s used in many parts of the world for prenatal sex determination, although its use for that purpose is a punishable offence in India.

In its report, researchers from the Pew Research Center say that once the test began to be used widely for prenatal sex determination, India’s sex ratio at birth — the number of boys born per 100 female births — began to widen quickly, going from 105 in 1971 to 109 by 1991.

As a result, India banned prenatal sex determination in 1996. Despite this, however, India’s sex ratio at birth reached its worst in 2011, with 111 boys for every 100 girls.

India’s improved sex ratio in the last decade (108 boys for every 100 girls in 2021 as against 110 in 2001) comes despite an increase in the number of pregnant women opting for an ultrasound. According to the report, the 2019-21 NHFS survey found that an ultrasound had been performed in 78 per cent of pregnancies in the five years leading up to the survey against about 19 per cent in 1998-99.

Researchers attribute this to Indian women opting for ultrasounds for “medical purposes”.

“Indian women seem to have become more likely to use ultrasound tests exclusively for medical purposes rather than to facilitate sex selection. Put another way, the sex ratio at birth following ultrasound use during pregnancy is now 109 boys per 100 girls. In the 2005-06 NFHS, it was 118,” the report says.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Covid-19 could undo progress on female genital mutilation. It needs a zero-tolerance approach