Nuh (Haryana): When Sohrab Khan leans into his mike and says “good morning” at 9 am, lakhs of people hear a loud crack before his voice booms through their radios.

Khan is the manager and one of the eight reporters and presenters at Radio Mewat, a community radio station in Nuh, Haryana, considered the country’s most backward district. Known as Mewat until 2016, Nuh lies to the south of Haryana, jutting into Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

The radio station has a total of nine employees, with one person overseeing its administration.

In Mewat, only 27 per cent of the households own TV sets, with most people either misinformed or out-of-touch with news. But in the last ten years that it has been in operation, Radio Mewat has evolved to bridge that gap.

Of the 431 villages in Nuh, the radio has the capacity to reach 170 of them. In a poor, insulated district, where not everyone can afford a smartphone or TV, the radio continues to hold popularity.

Though government guidelines prohibit community radios from discussing news, current affairs and politics, when Covid-19 struck, Radio Mewat emerged as a tool to dispel myths around the virus.

“When the lockdown happened, the district magistrate and the chief medical officer came to us to get the word out about coronavirus. We didn’t take a day off, and we worked through the lockdown,” Khan told ThePrint.

Nine months into the pandemic, Radio Mewat is still keeping its listeners informed about how the pandemic is shaping, and also local events in the district.

The radio runs from 8 am to 10 pm, with a 2-hour break in the middle. But its small team often works overtime to keep it running.

“We use information to empower people, but we’re also pushing the envelope without violating the code of conduct while broadcasting what people ought to know,” said Archana Kapoor, founder of Radio Mewat and the NGO, Seeking Modern Applications for Real Transformation (SMART).

Also read: Coming up, a radio station at every mission abroad to add muscle to India’s soft power

Shows on Covid and domestic abuse

Nuh is dominated by Meo Muslims, a conservative sect of Islam. The district is part of the larger Mewat region and is believed to be the birthplace of the Tablighi Jamaat.

As many as 79.2 per cent of the district’s population is Muslim, and a local clergy had told ThePrint in April that most people are connected to the organisation.

In March this year, the Tablighi Jamaat was blamed for hosting India’s first Covid-19 “super-spreading” event at its Markaz (headquarters) in New Delhi’s Nizamuddin, leading to stigmatisation of the community.

“The Meo Muslims in Nuh are already a very inward looking community, and when Covid and the lockdown happened, rumours were circulating and we had to deal with not only misinformation, but also with stigma,” Kapoor said.

She said immediately after the Jamaat incident, the team of Radio Mewat invited religious leaders, local police and district administration officials for panel discussions and live shows.

“We brought together religious leaders and asked them to dispel any myths about the Jamaatis and coronavirus. Every night, the district administration would email us about important information that needed to reach the masses. It played a big part in controlling the spread,” said Khan.

The show, ‘Corona se jung, Radio Mewat ke sung (Fight With Corona with Radio Mewat)’ broadcast in Mewati and Hindi, informed listeners about the precautions, Covid cases, and symptoms to look out for. It also hosted sessions with frontline healthcare workers.

Before the pandemic, Radio Mewat hosted shows on local events, agriculture and farming, local talent, interviews with retired government officials, and on schooling and education.

‘TV doesn’t have the same effect’

For the listeners, Radio Mewat is more than just a radio station.

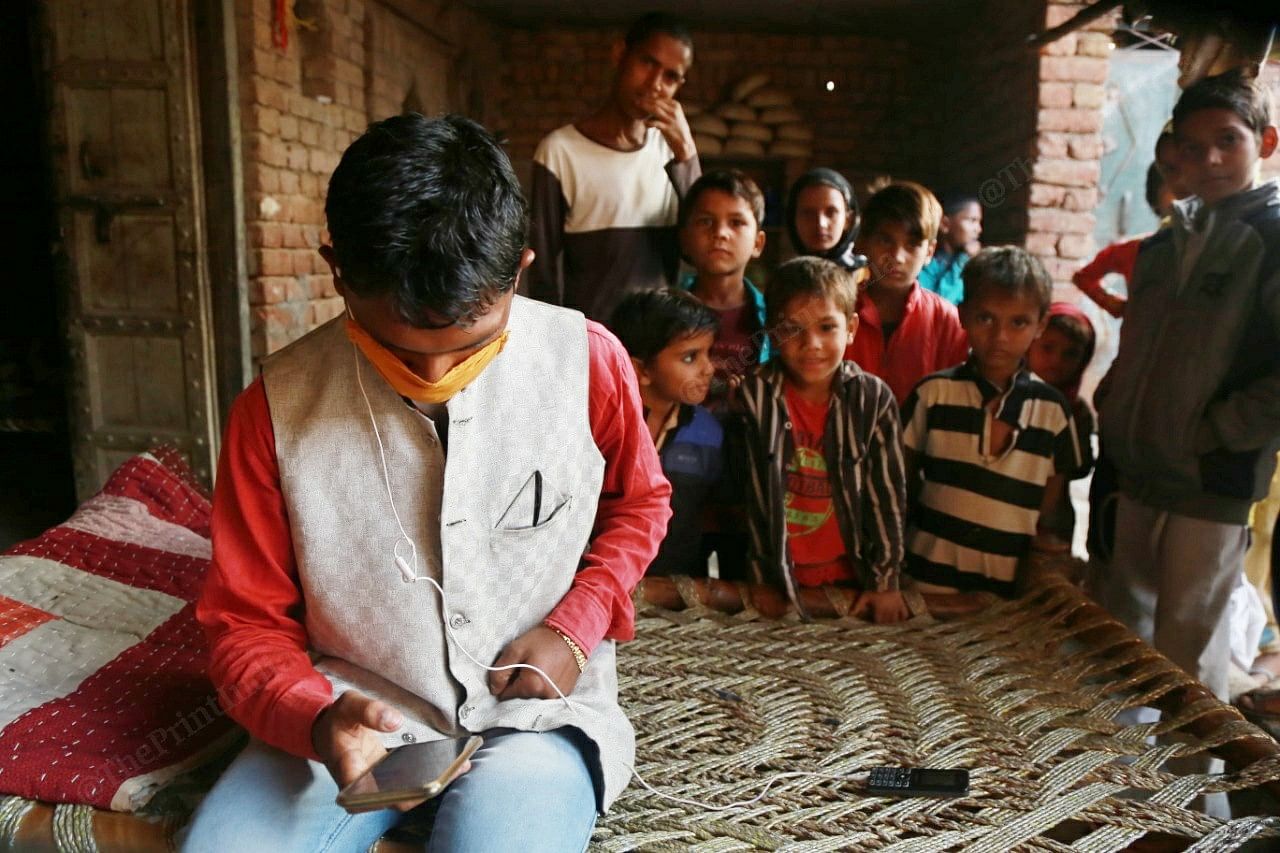

Wasim Akram, a 19-year-old student of Nuh’s Jogipur village, which has a literacy rate of just 52 per cent, said: “I listen to the shows about domestic violence, coronavirus, agriculture, and the daily updates. The radio was especially useful when schools were shut during lockdown. I get all my information from there. I play the radio on speaker and our whole family listens in.”

Akram has been a listener of Radio Mewat since 2010 when it was first launched.

In Dhanduka village, which has a sex ratio lower than Haryana’s average of 879, women gather around one radio set once a week to collectively listen to ‘Hinsa Ko No (Say No to Violence)’, a programme that brings forth stories of domestic violence and informs the listeners of their rights.

“We like to listen to it together and discuss it. We tell our families that we’re going for a meeting, and we come together to listen to the radio. The TV doesn’t have the same effect,” said Savita, a resident of the village, who only goes by her first name.

Doing a show on domestic violence was suggested by one of the presenters, 22-year-old Farheen Khan, a class 12 pass-out. The show, running for over a year now, gained new perspective when the lockdown brought with it more cases of domestic violence.

“I used to listen to Radio Mewat for its educational programmes. A few years ago, one of the presenters came to our village to conduct a workshop for uneducated women. I came with her to the studio one day and decided this was what I wanted to do,” said Farheen, who has been a presenter with Radio Mewat for two years now, and a listener for many years before that.

“I once spoke to a woman who had been sold by her husband to a group of men. She escaped, and called her family, and eventually spoke with us. These are the kinds of things that happen, and no one talks about it. I felt it had to be discussed. Things got worse during the lockdown, and we would get 30-40 calls a day,” she added.

Also read: Lessons through loudspeakers, community radio to help bridge digital gap in education

Difficult line to tread

Radio Mewat is one of the 310 community radios operating in India. Community radios are strictly monitored and they must adhere to restrictive guidelines to ensure they don’t become sources of misinformation or proxy networks for political parties. Only educational institutes or not-for-profit organisations are allowed to apply for a licence.

The radio, in some ways, does what the district administration cannot. Every day, up to five lakh people from various corners of Nuh can tune in to Radio Mewat, 90.4 FM, and learn about the schemes they are entitled to, the buzz of the town, and how to stay safe from Covid.

“We need everyone to know how to access schemes. Having a DM (district magistrate) work closely with the radio makes identifying problems easier. We identify the nature of the problem, and then work from there,” District Magistrate Dhirendra Khadgata told ThePrint.

In a district where literacy is just 54.08 per cent and poverty is near ubiquitous, the radio is able to act as a substitute for the lack of government infrastructure. But this is a difficult line to tread.

“We’re certainly not spokespersons of the government, but we don’t have the freedoms of commercial broadcasters either. We can’t talk about current affairs, or broadcast sports-related news, or critique the policies of the government. Even though we put the community first, we have to word ourselves carefully,” said Kapoor.

Sunita Mishra, who does the groundwork for ‘Hinsa Ko No’, said: “We don’t stop at just airing stories of domestic abuse. We hold sessions with the women, counsel them when needed, and speak to their families so they can have these discussions openly. It has taken a lot to get them to open up.”

“They don’t know the government helplines, but they know to call us,” she added.

When the lockdown forced their husbands out of work, the women listeners of Radio Mewat were roped in by SMART to make masks, of which they earned an income too.

Listeners to various programmes often call to ask for help on how to apply for schemes or lodge complaints, and Radio Mewat presenters said they always oblige to their requests.

Running a radio

Community radios like Radio Mewat must produce content with 50 per cent participation from the community. They are heavily subsidised for the work they do — spectrum fees amount to only Rs 22,500 per year compared to the lakhs of rupees commercial channels may have to pay.

But they also have to work under more restrictions. Community radios cannot have sponsors other than those from state and central governments, and other vetted public-interest groups like UNICEF. They also cannot run advertisements from anyone apart from the government and local businesses, thus narrowing down sources of capital.

“It costs us 1.6 lakh per month to run Radio Mewat, and we’re just about cutting it,” said Kapoor.

“During lockdown, we didn’t get any advertisements from the government. All the money was diverted to Covid relief efforts, and lots of community radios found it difficult to function. We were able to pull through, but barely, with help from benevolent foundations who were keen on spreading awareness for safety of people from the virus,” she added.

Sponsored programmes are keeping Radio Mewat afloat, and providing the presenters with their livelihoods, but Kapoor said the situation can improve if community radios are given more wiggle room.

“We keep our listeners informed about government schemes, natural disasters, health and other issues that relate with their day-to-day lives. The government should consider opening up sponsorships so we can earn a little more. It is all about trust, they will have to trust entities like ours, and allow sponsorships like the private radio channels get, especially after having a track record of serving our communities for over 10 years,” Kapoor added.