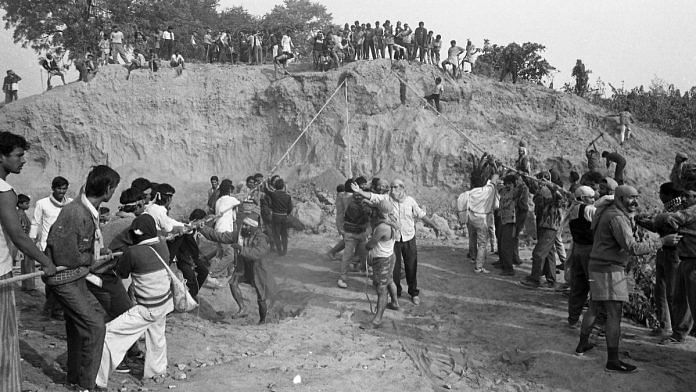

New Delhi: After 40 days of intense arguments, a five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court has wrapped up hearings in the title suit at the heart of the Ram Janmabhoomi dispute, which has been a potent communal flashpoint for decades.

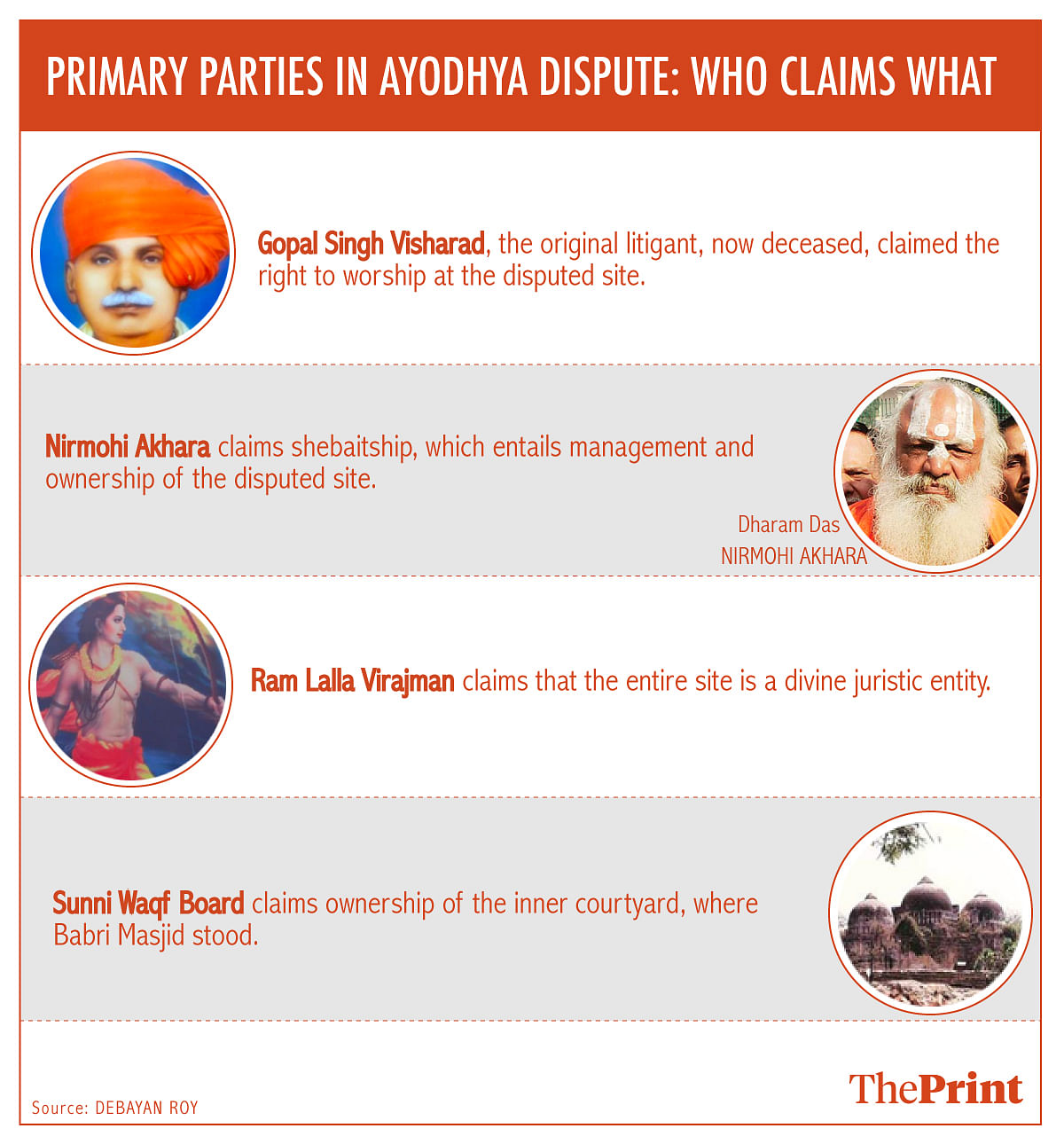

The verdict is likely in another month, before CJI Ranjan Gogoi retires in mid-November. The Supreme Court came into the picture when parties to the case challenged the 2010 Allahabad High Court order trifurcating the land between two Hindu parties — the Nirmohi Akhara and Ram Lalla Virajman, the deity installed at the site and seen as a juristic entity — and the Sunni Waqf Board.

The case at hand specifically deals with 14 petitions and the question of who among the three parties owns the land.

The hearing began early August, and is now the second-longest one to be heard by the apex court on a daily basis, beating the Aadhaar case, which was heard for 38 days. At 60 days, the Kesavnanda Bharati case continues to be the longest.

In a case where the sentiments of two communities have been evoked to claim ownership of a 2.77-acre plot, faith unexpectedly formed the pivot of arguments, with the case testing the applicability of belief and memory to the realms of law and evidence.

While the Nirmohi Akhara claims “shebaitship”, which entails management and ownership of the disputed site, the Sunni Waqf Board claims ownership of the inner courtyard, where the Babri Masjid stood until it was demolished by Hindu fundamentalists in 1992. Ram Lalla Virajman, the presiding deity who is a party, claims that the whole of Ayodhya is a divine juristic entity.

Also Read: The unusual and quirky questions Supreme Court asked during Ayodhya hearing

Nirmohi Akhara

The Nirmohi Akhara, which is a body of seers, claims to have been the worshippers and devotees of Lord Ram for over seven centuries. It thus stakes claim to “shebait” rights over the disputed site.

Shebaitship is a legal concept deriving from Hindu law where devotees are considered guardians of a deity’s daily affairs and associated property. It is not simply an office but accompanied by certain rights.

The akhara, which was founded by poet-seer Ramanand, operates on the collective memory of the sect — there is no written text, just oral traditions.

In 1885, the akhara filed a plea in the Faizabad district court — the district has now been renamed Ayodhya — seeking permission to build the Ram temple. However, the court had disallowed the request, keeping in mind the potential communal overtones of the case.

The akhara finally became a party in 1959 when a Faizabad court was hearing the plea of Gopal Das Visharad, the primary litigant in the case, who had filed a plea for Ram Temple construction in 1950.

In the apex court, the akhara has argued that even though the deity is a litigant in the case, the “shebait” has the right to institute and maintain lawsuits on the deity’s behalf.

Advocate Sushil Jain, making a case for the Hindu body, said if the verdict was not in favour of the akhara (is not given shebait rights), it would not accept the final ruling even if the land goes to Ram Lalla Virajman. When the Supreme Court pointed out that both the Hindu bodies “fall together and stand together”, the akhara withdrew the argument.

Citing a series of high court verdicts and “witness testimonies”, the body argued that it had been in possession of the site since 1934 and that Muslims did not offer namaz there.

Ram Lalla

Ram Lalla Virajman became a legal party in the current title suit only in 1989. Ram Lalla, who represents Ram as an infant, is not eligible to move court, which is why former Allahabad High Court judge Deoki Nandan Agrawal moved the high court as the deity’s “next friend” to authorise his claim as a litigant. In the same petition, the janmabhoomi (the birthplace) became a separate entity and sought title right over the entire disputed property.

Soon after the akhara wrapped up its arguments, Ram Lalla Virajman and other Hindu bodies, considered a single party by the Supreme Court, stepped in, claiming that a massive Ram temple existed just where the Babri Masjid was built by the Mughal emperor Babur in the 16th century.

They claimed that not just the disputed site, but the whole of Ayodhya, by virtue of being Ram’s birthplace, was a juristic entity.

Senior lawyer K. Parasaran, a former attorney general, represented the deity. To argue for Hindus’ ownership over the land, he cited a pre-Independence verdict where it was ruled in the Masjid Shahid Ganj case that a mosque is an area to pray and cannot be compared to a Hindu idol, which is a legal entity.

He said in Hinduism, the presence of idols was not necessary for a place to be regarded a place of worship.

Citing the ‘Skand Purana’ and other religious texts, Parasaran claimed that there indeed existed a massive temple structure, which rested on pillars beneath the site.

He also quoted a 2003 Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) excavation report that talked of a structure found underground dating back to the second century BC. He argued that Hindu imagery was found in abundance on the mosque’s premises, which proved that Muslims could have never offered prayers at the site as it would have been against Islamic tenets.

Photographs of sculptures found at Babri Masjid — before it was demolished on 6 December 1992 — were presented as well.

Another piece of evidence was a report prepared by the Faizabad commissioner in 1950, which is said to prove the existence of 14 pillars replete with Hindu imagery.

It was claimed that pillars at the site bore the image of a Garuda — a bird mentioned in Hindu mythology — flanked by lions. “Muslims have no images of humans or animals in mosques,” Ram Lalla argued.

Travelogues by English merchant William Finch, Italian missionary Joseph Tiefenthaler, and Irish author Montgomery Martin, from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, respectively, were also presented to back this argument.

The Supreme Court, however, did raise questions about the production of new scriptural evidence by the body, noting that any evidence not brought on the record at trial stage would not be considered.

Another argument put forth pertained to adverse possession of the disputed site, which means claiming someone else’s property through exclusive and continuous hostile possession. This argument has solely been made by Ram Lalla against the akhara and the Sunni Waqf Board.

Ram Lalla argued that the akhara and the board were in adverse possession as the land originally belonged to Lord Ram and no one could claim possession of a deity.

Also Read: Ayodhya trial fallout: Lord Ram’s growing ‘descendants’ — Congress & BJP leaders, hotelier

Sunni Waqf Board

It was after the Hindu bodies wrapped up their arguments that senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan began to make his case on behalf of the Sunni Waqf Board.

The board, which became a party to the suit in 1961, claimed that prayers were offered at Babri Masjid before it was razed.

Dhavan said the word “Allah” was found inscribed at the entrance of the masjid, which he argued was clear proof that it was indeed an Islamic structure used for prayers.

He submitted a set of reports by historians to claim that the Babri Masjid was never built by demolishing a temple.

The primary contention of the Muslim side has been that mere belief that Lord Ram was born exactly under the central dome of the Babri masjid or the Ram Chabutra does not give Hindus ownership of the disputed land.

The senior lawyer said there was no evidence of any title they held over the land, or to prove Ram was born under the inner dome as there “is no physical manifestation of the belief of Hindus”.

He said what was definite was that Hindus had rights to enter the mosque premises and pray. “However, they trespassed into the land and surreptitiously installed the idols on 22-23 December 1949.”

Senior advocate Zafaryab Jilani, also representing the Muslim side, argued that namaz was continuously offered at the disputed site, which he sought to prove by presenting documents that purportedly proved the appointment of an imam and theft of mats laid for Friday prayers.

Meenakshi Arora, another senior lawyer arguing for the board, disputed the findings of the ASI report quoted by Ram Lalla.

She said archaeology was an inferential science and the court should place little weight on the opinions of archaeologists. She also sought to point out inaccuracies in the report.

According to the report, she said, the pillar bases found beneath the mosque were constructed at different heights — which, she argued, could not have held up a structure.

Also Read: The Ayodhya connection to Asaduddin Owaisi’s Delhi home