Banaskantha: Torn pink, green, blue sarees hanging on barbed wires mark the entrance of the Vadia (or Vadiya) village in Gujarat’s Banaskantha district. Historically referred to as the “land of sex workers”, here, girls of the Saraniya community — many as young as 12 — are forced into prostitution, often by the men of their families.

It is not easy to gain entry into the village. When this reporter visited Vadia, a group of men sat guard on a charpai (cot). One of them then came running to ask the purpose of the visit. At this point, you either have to have the “right answers”, or count on local assistance.

Once you enter, a message is sent across the village to hide the young women. Only if you are a regular client, or a social worker, are you let off without anyone demanding money or threatening you.

There are no vegetable or other vendors on the streets — only two to three shops that provide basic rations. The village does not even have a pharmacy or a public health centre (PHC). One has to go to Tharad, around 30 km away, or to other nearby villages, for such basic necessities.

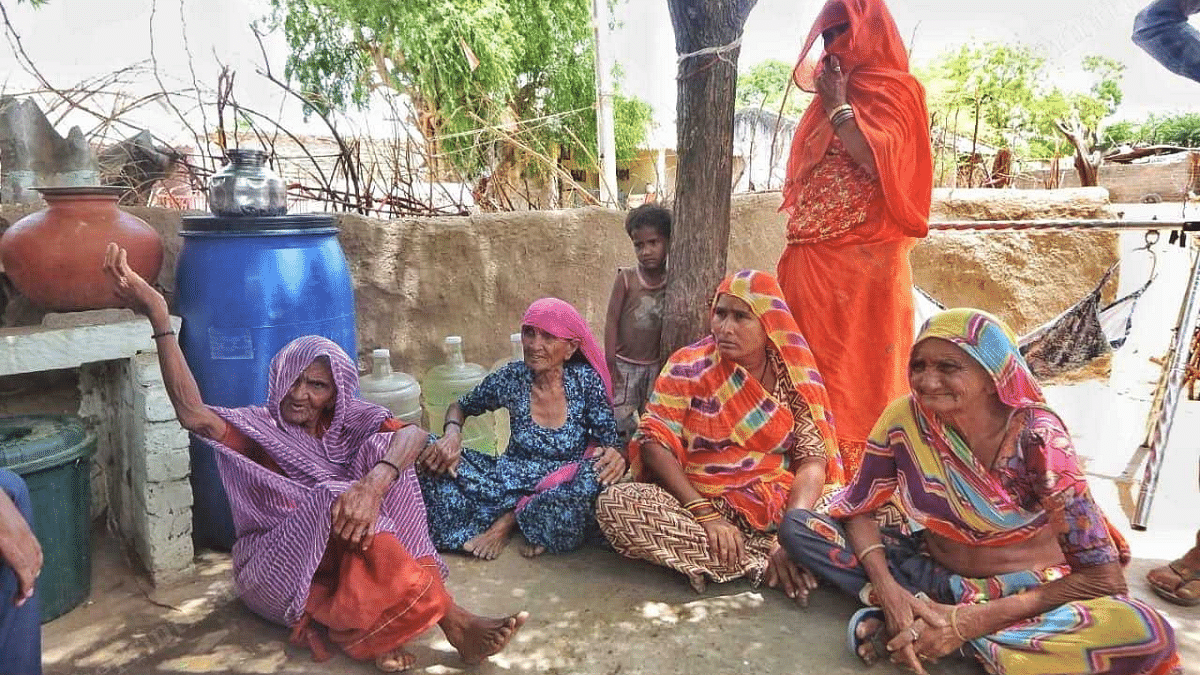

As you reach the houses, older women dressed in colourful ghagra-cholis come out of their houses — their eyes both curious and fierce. The younger lot almost immediately covers their faces with veils.

Women in Vadia remained unmarried for generations — stalked by the stigma of indeterminable fatherhood. A glimmer of change arrived in 2012, when the first mass marriage ceremony was held after NGOs managed to convince some of the families not to force their daughters into the flesh trade.

Since then, every year, four to five mass marriages have been held in Vadia.

Desperate to rescue young girls from being forced into sex work, NGOs and social workers have come up with a solution — girls as young as seven are engaged to boys from among their relatives and nearby villages. Once a girl is engaged, an unwritten code kicks in to protect them from the fate of the generations before them.

Some residents, meanwhile, are taking their children away from it all — to a future with an education.

While change has arrived, challenges remain.

From patriarchy to the burden of HIV left behind by customers who refuse to use protection, the women are fighting several battles together.

Also Read:In Gujarat, paper leaks an organised crime. New law has to crack inter-state criminal nexus

Ignorance around HIV

According to government figures, there are a total of 750 (2023, projected) families in Vadia. There are 600 registered voters — 250 men and 350 women.

In the village, ThePrint met Bhikki Ben, a former sex worker who has been HIV-positive for the past four years and lives a life of ostracism. The inhibition of women around her is visible — reluctant to believe the infection doesn’t spread from just being around someone who is HIV+, they distance themselves from her.

“I started sex work when I was 12. At that time, we would get Rs 500 for a night. I don’t know how I got HIV, but men don’t want to use condoms, even if we carry them,” she said. “Since I have tested positive, I have lost everything.”

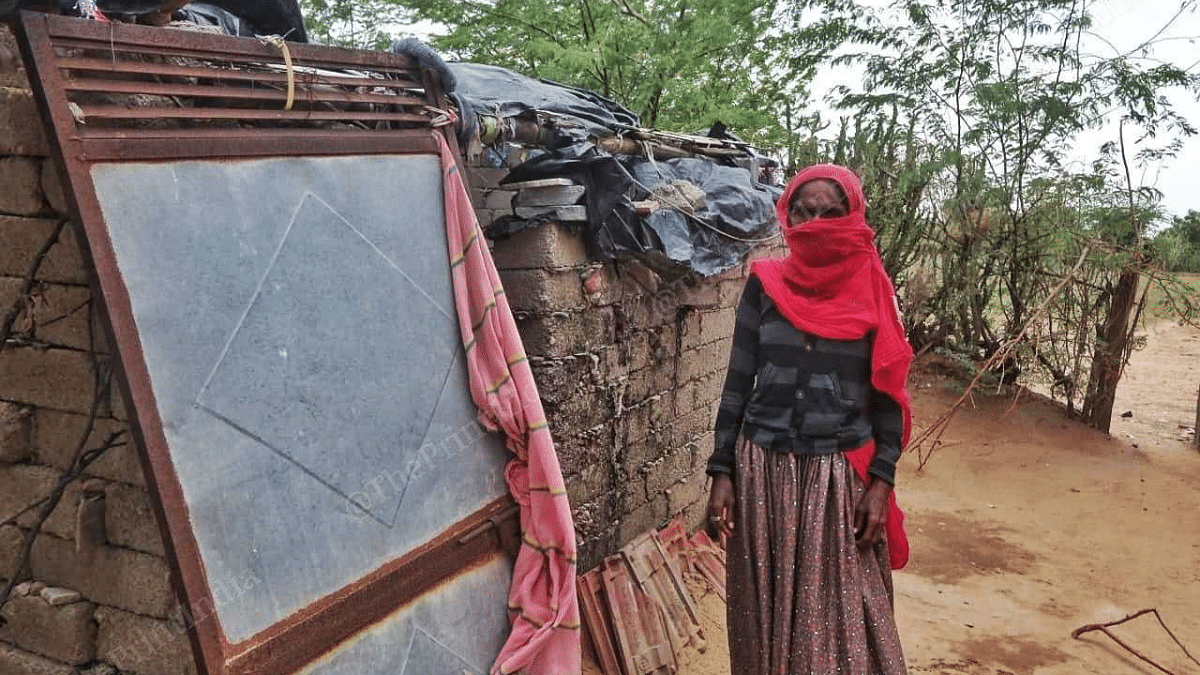

Even her own family steers clear of Bhikki Ben, who lives in a cramped kutcha house on the outskirts of the village.

Her house has two mutkas (pots) for drinking water and one dilapidated chulha, and she survives on rations given to those with the Below Poverty Line card. The tarpaulin sheet covering the house is torn in places, leaving it exposed to the elements.

Her elder sister Suriya and the rest of her family live in a pucca house right next to Bhikki’s home, but she isn’t allowed inside.

“We don’t want her to come anywhere near us,” said Suriya, adding that she suffers from a chronic kidney ailment. “We don’t care if HIV spreads by touch or not. If any of us catches it, who will feed us?”

Suriya also quit sex work some years ago. “There is no demand for women above 40. Now, my daughters support me,” she said.

Dressed in a yellow ghagra choli, Suriya’s daughter Sonal jumped into the conversation after a phone call.

As she smiled, a gold tooth peeked through. Braiding her hair for a client she was to meet in two hours, Sonal, who is in her mid-30s, stopped right at the door when she spotted Bhikki. “We try to give her food whenever there is something left over,” she said.

Sonal said she charges somewhere between Rs 1,000 and 2,000. The rate, she added, is higher if the client wants to come to her house, and lower if she goes to a hotel in Palanpur city. The price comes down further if he is a regular client.

Both Bhikki and Suriya were forced into sex work by the men of their family, the former said.

That line of work gone, Bhikki now finds herself in deep despair. “I have no land and my own family doesn’t want to take care of me or even feed me. I survive on the rations given by the government and free medicines,” she said. “I am just waiting to die, and I know, no one would touch my body even then.”

Bhikki is far from the only HIV-positive person in Vadia, but she is perhaps the only one whose condition is known publicly.

According to Sharda Ben Bhati, a social worker who has been working for the rehabilitation of these sex workers for a decade, there are close to 40 women who have tested HIV-positive.

“I work as a government pointperson for HIV patients and give them medicines. Bhikki suffers from this isolation because people came to know about her condition,” Sharda said. There are others too, but their identity hasn’t been out in the village yet.”

According to K.S. Dabhi, sub-divisional magistrate (SDM), health workers from the Arogya department visit Vadia regularly. Social workers and NGOs have tied up with the administration to help HIV patients with medicines, he said.

“There is a PHC in another village. Doctors are available in Tharad town. We try to make them [sex workers] aware about HIV and how it spreads,” he added.

Women of Vadia

The women of Vadia might be the earning members of their families, but their lives are controlled by men — their old partners, sons and brothers.

“Several NGOs and the government have tried to empower the people of Vadia. But it is the men who don’t let these women move on from sex trade, which is why the progress has been slow,” said Banaskantha MP Parbatbhai Patel.

The women of the village are not even allowed a lone conversation without at least one male interrupting them.

“We have lived with some men, but they keep changing their partners. We earn and they spend,” said Amri Ben, a 30-year-old mother-of-four who is engaged in sex work. “Now, we don’t know any other way of earning an income,” she added, looking at her youngest daughter as she slept in her cradle.

All the while, Amri’s brother — described as a drug addict — kept nudging her.

Amri said she was pushed into prostitution when she was 14. “The man living with my mother forced me into it. There was no question of resistance. It is considered tradition here,” she added. “We don’t really have a choice.”

According to Sharda Ben, the social worker, the sex work is no longer restricted to the village. “When I started visiting this village a decade ago, there would be lines of clients outside houses,” she added. “Now, most women go to the city for clients.”

The Saraniya community’s encounter with sex work is said to have begun after Independence.

During the times of the 16th-century king Maharana Pratap, the Saraniya community, a nomadic tribe, earned a living by sharpening knives and other weapons for his army.

During the British era, the women danced in darbars and palaces, a source of income that ceased to exist after Independence. It is believed that 13 sisters, who had danced in these darbars, subsequently migrated from Chittorgarh to Vadia and started sex work.

“Somewhere between 1963 and 1965, the Indian government gave some 200 acres of land to these 13 sisters, but the lack of a water source made farming difficult. The land was given to the members, the 13 sisters of the ‘Saraniya Stree Sahakari Mandali’, which now has 40 members,” said Mittal Patel, founder of the NGO Vicharta Samuday Samarthan Manch (VSSM), which works for nomadic, denotified and deprived tribes.

Also Read: ‘Reverse dowry’, rape & ‘good houses of bad husbands’ — the hidden stories of Gujarat’s child brides

Scrambling for water

A few men and even women (who have quit sex work) of Vadia are engaged in farming, but water is a big issue.

In 1998, the government dug borewells in Vadia, but they soon became dysfunctional. After efforts by several social workers and NGOs, these borewells were revived, but a water shortage continued to linger. Ever since, there has been a demand for more borewells.

“There has been an acute water crisis here, but little has been done to solve it. Borewells were supposed to be dug, but so far it hasn’t been done as there is a constant war between the two villages — Vadgamda and Vadia — as to where they should be located,” said Sharda Ben.

But when ThePrint asked SDM Dabhi about the tug-of-war over the location, he denied the claims and added that the issue is between the people of the same village.

“There is a fight between two groups of people of Vadia over the location of the borewell and not with the people of Vadgamda,” he said.

“We had a meeting with both groups two months ago in my office in the presence of the sarpanch and they were convinced. But later, they back-tracked, so the borewells weren’t drilled,” he added.

Vadia and Vadgamda fall under one gram panchayat, along with Kothigam.

A walk through the village makes the water scarcity in Vadia clear. Pointing at a mini truck off-loading water bottles, Santosh Ben, a resident, said, “We even have to buy water that costs Rs 20 for 20 litres, for drinking purposes.”

According to the SDM, the water from the water supply board reaches the village, but the residents are demanding borewells. He, however, acknowledged that water scarcity could be an issue.

“The line of their water supply comes through a different village, and sometimes due to illegal connections, it is possible they don’t get enough water supply,” he added.

Silver linings?

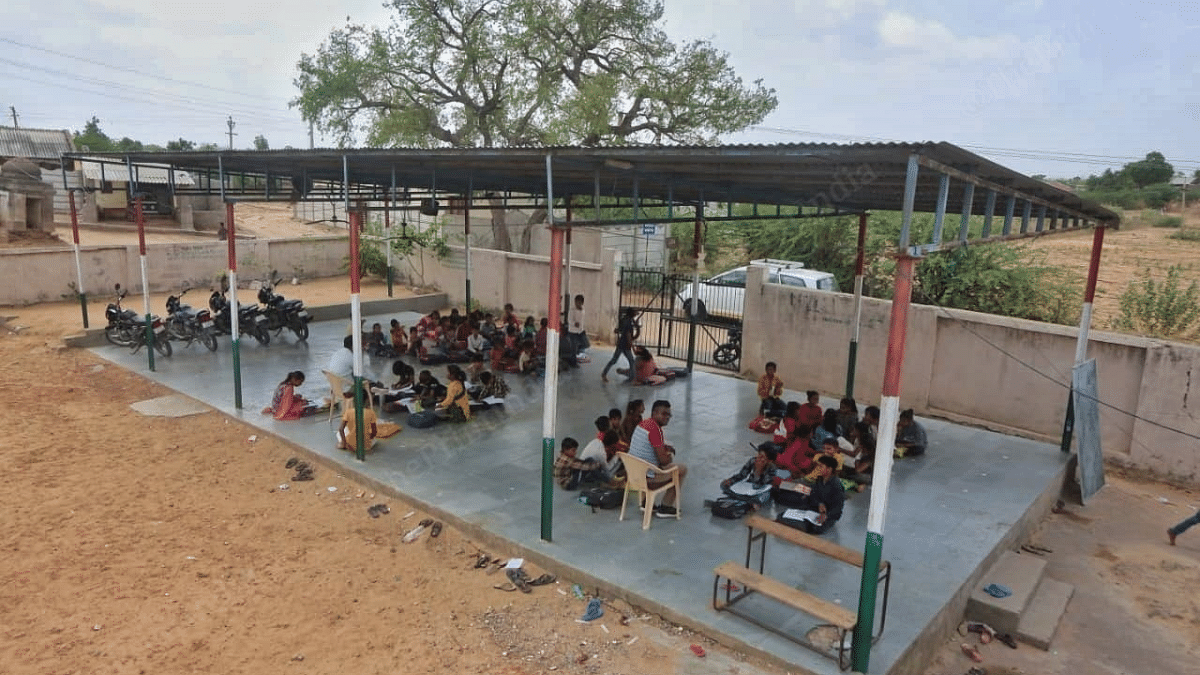

The Vadia Primary Government School is right at the entrance of the village, where some 186 children attend classes in the verandah outside.

“When we started, it took a lot of effort to convince the parents to send their children to school. Now, some of them want their kids to be educated. This is a change, but there is a long way to go,” said Sharda Ben.

The school has been torn down for reconstruction, but no one here knows exactly when it will be done.

SDM Dabhi told ThePrint that schools in other villages are also being reconstructed, and the work will begin soon. The primary school is to be converted to a middle school and eight new classrooms are to be constructed there.

M.J. Bhai Savashi Bhai, who has been the principal here for four years, travels 7 km on his bike everyday from Moti Pavad village to reach the school. “There is no proper drinking water facility in the school as well,” he said.

Some of the children of this village live in a shelter run by Janta Foundation, founded by Sharda’s daughter Mansi, in Tharad. As many as 22 children — most of them girls — from Vadia stay here.

“They study in nearby schools and live here. Some other children come here after school for tuition, but they go back. Those young girls that have been taken out of Vadia have completed graduation from Palanpur. Some families have also moved out of here to Palanpur,” said Sharda.

The NGO, VSSM, also runs a hostel in Tharad for the same purpose — taking young children out of the village.

According to social workers, the first change in the village came with the mass marriage in 2012, when eight couples were wed.

The mass marriages have continued since, with some four-five couples getting married every year. Loans are also provided to former sex workers who want to start their own businesses — mostly keeping livestock.

ThePrint met some married couples, including Kanti Bhai and Kami Ben, who have sent their children away for a shot at an education.

The couple makes a living through farming. Kanti’s parents never got married, but quit sex trade to make a better life for themselves.

Kanti and Kami have four children, all girls, who have been engaged. The eldest among them is Tinkle, a Class 6 student. She is engaged to Kanti’s nephew, who lives in the Janta Foundation shelter.

Anil Bhai and Bachi Ben, another couple, got married in 2012. Bachi goes to a farm, some 4 km away from Vadia, to work everyday. Anil works on the 2 acres of farmland that was passed on to him and his brother. Additionally, he also trims buffalo horns when they begin to dig into their skulls.

He charges Rs 200 for two horns. Their daughter Sita — also engaged — lives in Janta Foundation’s shelter.

While Tinkle wants to be a doctor, Sita wants to be a police officer.

“I came here some five years ago. The environment in Vadia isn’t good, so I stay here,” said Tinkle of the shelter. “I don’t go there even during vacations. My parents come to see me here.”

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: Haryana’s desperate bachelors bought wives. They turned out to be ‘loot-and-scoot’ brides