Mangaldoi, Assam: It was in Mangaldoi in Assam’s Darrang district that the seeds for updating the National Register of Citizens (NRC) were sown four decades ago. Two days after the final NRC list was published, it is Mangaldoi that serves as the perfect case study to know all that has been wrong with this complex exercise, its redundancy and the sordid tales it has led to.

On 31 August, the final NRC list excluded around 19 lakh people, down from 40 lakh left out in the draft versions. The figure in the final version may have halved, but the complexities seem to have doubled. Chaos, uncertainty, suspicion and grave discomfort have seeped in, all of which point to how the process and its execution have achieved precious little.

Even though the actual process of updating the NRC began in 2015, under the directions of the Supreme Court, the push for it came in a by-election at the Mangaldoi Lok Sabha constituency in 1978 that was forced by the death of its sitting MP Hiralal Patwari.

At the time, it was noticed that the number of registered voters had suddenly swollen, sparking suspicion that this was due to the influx of immigrants from Bangladesh. Thus began the six-year Assam Agitation in 1979, which ended with the signing of the Assam Accord that promised to update the 1951 NRC.

Exactly 40 years later, Mangaldoi exposes the absolute mess this contentious process has become, and why the way forward seems sketchy.

The chaos

The most glaring issue with the NRC outcome is how it has ended up dividing families, mostly those belonging to religious and linguistic minority communities.

As ThePrint travelled through Mangaldoi, there was barely any family belonging to the minority community that wasn’t facing this situation.

“I have been a government school teacher since 1994,” says Abdul Bareque. “I come from a reputed family here and my father’s elder brother was a freedom fighter. This road is named after him. But my name hasn’t appeared in the NRC.”

To make matter worse for Bareque, most of his family members have made it to the list.

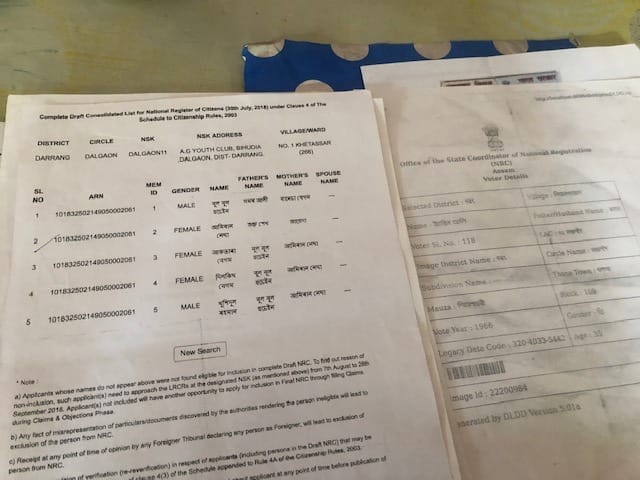

“Even more ridiculous is that fact that my parents’ names have appeared, as have those of my siblings, children, nieces and nephews,” he says. “Only my younger sister and I haven’t made it. We all submitted the exact same legacy documents.”

He isn’t the only one facing this peculiar situation. The list seems fairly endless.

Abdul Salaam, in his fifties, of Mowamari village, says, “My brother and I gave the same legacy documents; we live in the same house. And yet, his name has appeared, but not mine. How is that even possible? Obviously, something is wrong. This is our birthplace.”

In Shyampur village, residents have the same tale to narrate. “My children’s names have appeared, but not mine,” says an exasperated Abdul Karim. “How is it possible that they are Indian citizens but I am not? Their legacy documents are derived from mine.”

Most say that after their names didn’t appear even in the final drafts, they filed claims. Hearings were conducted, their relatives whose names had appeared were called in for verification and more documents were sought. Nothing, however, changed.

NRC officials, meanwhile, claim applicants often have ‘errors’ in their individual documents, such as spelling mistakes or nicknames instead of actual names, which leads to such confusion.

“The legacy documents may be the same. But suppose one brother gives all his documents correctly and the other has technical errors to do with spellings, date of birth, mentioning nicknames and not actual ones etc, then issues arise,” said an official who did not wish to be identified. “Also, we have found many people to be lying about their siblings and relatives to try and get in.”

Also read: With Assam NRC, the truth is also out — it was a pointless exercise all along

‘Price of coming from Mangaldoi & being Muslims’

While some ascribe these discrepancies to the “discretion and subjectiveness of the disposing officer”, others have more drastic conclusions.

“This is where the Andolan (movement) started. They had no option but to inflate the numbers to show the concerns had been genuine,” says Muhammad Fazal of Mangaldoi Gaon. “Thus, they decided to do this arbitrary thing of keeping half the families in and half out.”

Several echo this sentiment and add that this is also a way to “target minorities and use them to inflate numbers”.

“Look at the numbers, the highest exclusions have been in Darrang district, in minority-dominated areas,” says Ainuddin Seikh, working president of the All Assam Muslim Students’ Union (AAMSU).

“In Mangaldoi circle, around 30 per cent have been excluded. But it is the same pattern — some members of a family are in, others are out. This has led to chaos.”

The long road ahead

The way forward, meanwhile, seems daunting for most. With their names excluded, a long judicial process will follow, beginning with an appeal in the Foreigners’ Tribunal.

Besides the logistical inconvenience, the cost of the entire exercise is pinching many.

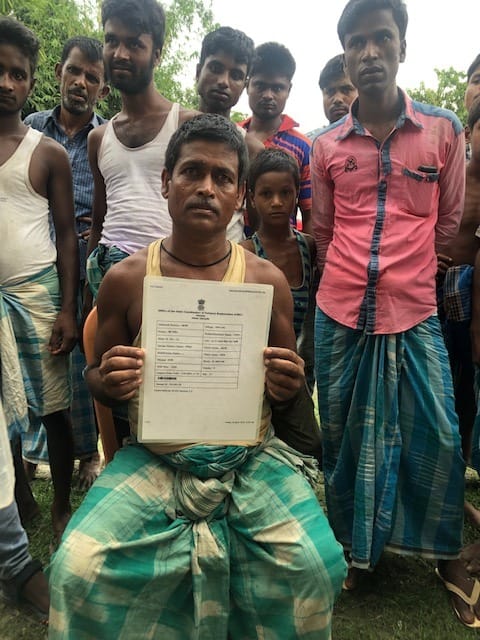

“None of us are rich people. How will we afford lawyers, the travel and the time it will require, thus keeping us from working?” asks Tahar Ali, 25, of Khetassar. “And even if we do start the process, our documents remain the same. How do we solve that?”

Some, who belong to extremely deprived sections, say they will do nothing and simply “go on like this till the government throws them out”.

For now, Mangaldoi — which in a way is responsible for NRC — shows why this exercise has created nothing but panic, confusion and suspicion.

Also read: Children out, parents in: The real challenge begins now that final Assam NRC is here

This whole exercise will turn into a huge humanitarian disaster bringing International Shame to India… Under the misrule of Modi and Shah, India lost its essence of being a progressive democracy.

This doesn’t mean the whole process should be abolished. Legitimate cases should be re examined. Plenty of time should be allowed to re verify the family and personal records.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has urged India to ensure that the highest standards of due process are followed and that these two million people are not left stateless. As a country that has long aspired to a permanent seat on the UNSC, India is bound to consider these suggestions / advice with respect.

Some humane solution will have to be found. The starting point is India’s solemn promise to Bangladesh that there will be no deportations. Add to that, no detention centres. Someone who has been a teacher since 1994 has face value. As does someone whose parents or whose children are found to be citizens. Either the Tribunals should be advised to be most liberal, or some alternate method should be found. Give people the benefit of the doubt, instead of putting the entire onus of proof on them. Cannot recall the last time one has looked at the apex court with a feeling of such regret.