The Indian economy is undergoing a transformation from one that is dominated by the informal sector to one in which the formal sector has a larger role. The Goods and Services Tax (GST), introduced in 2017, is expected to push the economy towards greater formalisation. The current consumption slowdown appears to be a symptom of this transition. The transition process will likely be long as it requires growth in firm productivity.

The impact of formalisation of the economy on consumer goods producers in India is visible in sales data. Firms that were competing with informal-sector firms saw a rise in sales when GST was first introduced.

This is not surprising as they already had systems in place for tax compliance. They were more productive. As a consequence, even while they were paying taxes, they were able to compete with informal firms that were largely not tax-compliant.

When GST was introduced, their informal-sector counterparts suffered from compliance costs. The pattern of higher sales of formal firms after the introduction of GST is clearly visible. We do not have data for informal firms, but anecdotal data seems to suggest that they suffered after the introduction of GST.

Interestingly, in the periods following the sharp rise in sales, formal-sector firms are seeing a slowdown in sales. The shutting down of informal firms or decline in their market share is likely to have led to job losses. This job loss is then likely to show up in lower income and expenditure of households. Since this sector was so large, the effect is likely to be significant for the economy as a whole. This may not be the only reason, but seems to be one possible reason for declining sales growth.

As we would expect, consumer goods companies that were competing with the informal sector first did quite well for a quarter or two after GST and demonetisation in 2016.

However, in recent quarters in 2019, they have started witnessing a slowdown. For example, biscuits sold by formal-sector firms gained as informal-sector biscuit producers lost out due to GST and demonetisation. But later, when the shutdown of the informal firms and job losses started to kick in, demand for products such as biscuits slowed down. This slower demand then affected the sales of these companies.

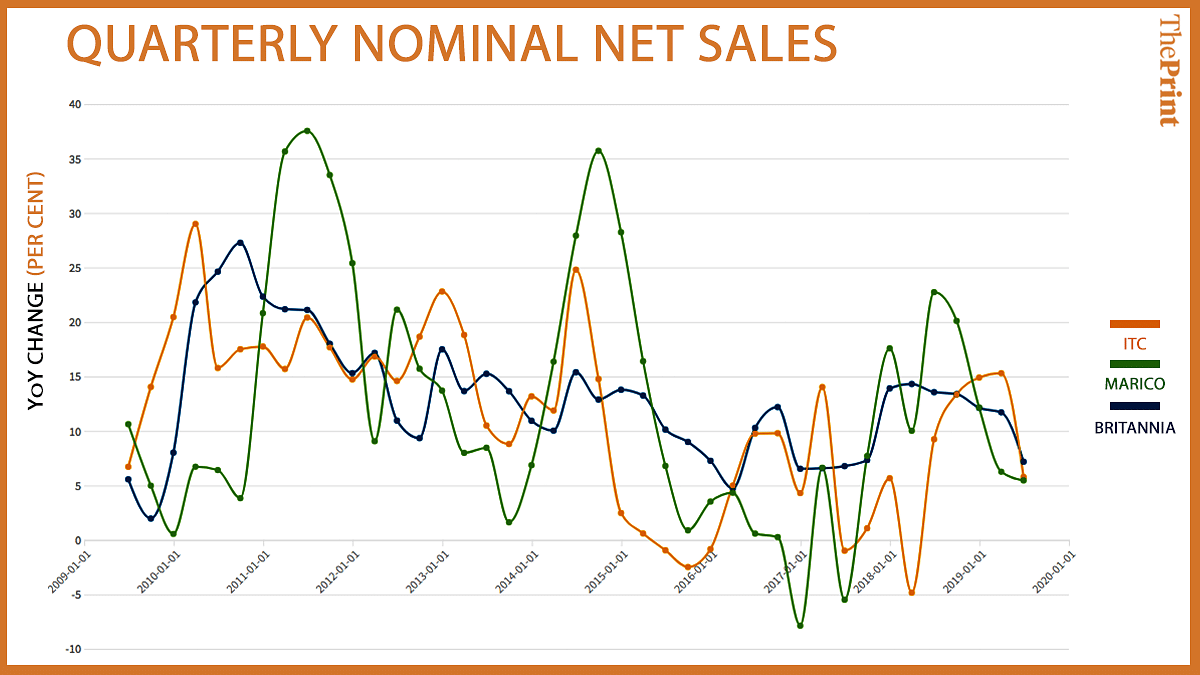

As an example, we look at quarterly net sales of Britannia, ITC and Marico. Looking back to the beginning of 2017, at first, sales declined due to the impact of demonetisation as there was a demand shock due to the withdrawal of currency notes. Then, the impact of GST on their informal-sector competitors seems to have helped sales growth of these firms. After a while, we see that their sales decline.

Also Read: To increase cooperation, BRICS countries need bottom-up approach, people-to-people connect

Govt needs to be gentle

Most households in India earn their livelihoods in the informal sector. Estimates of people employed in the formal sector are sometimes pegged at around 5 to 6 per cent.

If there is a decline in informal-sector growth and jobs, it is not surprising that overall consumption demand would fall. This would also explain why we did not see a rise in demand despite the election quarter, when spending by political parties was double of what it had been in previous elections.

At present, we are seeing a decline in investment that started seven to eight years ago continuing, and the new phenomenon of a decline in consumption demand beginning to show up from the first quarter of this year.

Many people are asking if the cut in the corporate tax rate will lead to an increase in consumption demand. Clearly, it will not. The cut in the corporate tax rate is a response to the decline in investment that began in 2012. A cut in corporate tax rates was first proposed in March 2015. This was implemented only piecemeal and large corporates in India were excluded from this cut.

In the meantime, other countries continued to reduce corporate tax rates. The cut in tax rates is expected to increase the incentive to invest.

A corporate tax cut might have been adequate to bring back investment growth in 2015 when consumption demand was not an issue. The global economy was doing well. Firms looking to export would have found it relatively more attractive to set up production facilities in India then with a high corporate tax rate.

After the introduction of GST, many firms are likely to have postponed investment until the market stabilised. Today, with low consumption demand, investment may remain subdued.

There are no short-cuts to pushing demand as the phenomenon is part of a larger trend towards formalisation. To some extent, income-tax cuts will help as they will put money into the hands of people who will spend it. The choice for the government is not easy as GST revenue is not as much as expected and not growing fast enough. Still, tax rates should be cut because this is not a “normal” time.

A tax reform as big as GST in an economy that is largely informal was expected to be disruptive. There was no clarity on what would be the effects and how policy-makers should react to them. Also, no single policy will be able to solve the present demand slowdown. Eventually, more productive firms have to increase their market share. But this process takes time. The best response of the government is to be gentle in its regulations, tax demands and interference in businesses that are in the tax net, struggling with compliance and with the new environment.

Ila Patnaik is an economist and a professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. Views are personal.

Also Read: Financial sector needs bold reform to fix slowdown. Modi govt has time & numbers to do it

With respect to GST, the government was in a fix. The 101st Constitutional Amendment allowed only one year life for old tax laws like VAT., Central Excise and Service Tax, which would expire on 30th Sept 2017. Politically, the government also needed at least one year buffer time to iron out the adverse effects of GST. So, it was a do or die situation for the government. The other alternative was to defer GST implementation to the next elected government. In view of Constitutional amendment, this option was more or less closed. Such deferment would have required another Constitutional Amendment to restore old laws, two thirds majority approval in Parliament and ratification by 50% of the States. That would have been unthinkable. Anyway, GST was a structural reform, which was bound to happen sooner or later.

Since when has it become prudent to judge a bank by one parameter alone? here the author is looking only at deposit vis a vis market capitalisation. In a falling equity market it is but natural that share prices are affected by bearish sentiment and hence market cap is affected in such a scenario. It is also common that in the absence of stability in investment avenues like share market, gold, real estate and nbfc bonds the natural flow of savings is into bank deposits. In such a scenario which is prevailing now in the country deposit growth is being measured against a lower market cap position thus leading to an unfavorable ratio. It is but natural that those Pvt sector banks which have higher shareholding with foreign investors will have a higher equity base. As per the government’s policy, foreign investors can invest up to 74% of paid-up capital in private sector banks. Hence those banks with higher FDI investors have higher equity than those Pvt sector banks which have only domestic investors. This is not a major concern as a bank’s health is determined by its profitability, NPA ratio and capital adequacy ratio.

The Basel III norms stipulated a capital to risk weighted assets of 8%. However, as per RBI norms, Indian scheduled commercial banks are required to maintain a CAR of 9% while Indian public sector banks are emphasized to maintain a CAR of 12%. All banks in India have to follow Basel III norms for computation and reporting of capital adequacy ratio. One of the so called weak banks as per this silly article is Federal bank which had reported car of 14.14% as at mar-19! Incidentally the bank also reported it’s highest ever net profit in the second quarter ended sept 2019.

Why did the reform have to be disruptive? Has it been disruptive because it was not implemented well? That Indian economy needs to be formalised there is no doubt. But was this the only way?

And for the author real people seem to be ghosts who simply suffer collateral damage.

This is Mao and Stalin style dirigismo.

Good analysis.both Demonetization and the poor implementation of GST have severly affected the economy.The demand side has been seriously affected.unfortunately the govt refuses to see the reality.The financial policies are being shaped by babus with limited vision who have to please the govtEven the few economists in the govt have to fall in line.We need bold policy decisions.we are heading for a major recession!

The govt is hiding behind false statistics to cover up its failures!

The suggestions by Yashwant Sinha and others to increase demand by increasing Govt investment in large infra projects and via expanded MNREGA probably indicates the best way to restart the demand cycle. The earlier Congress idea of a basic income for the poorest 25% of families is another idea. But we need a Govt that is shorn of ego and grandstanding and is willing to look at good ideas from any quarter.

Ultimately, formalisation of the economy is a must for a country of the size of India. We cannot do juggad all the time. The attitude towards laws and rules need to change as well by the govt as well as the general population

Within days it was clear that Demonetisation was an unmitigated disaster. In two months, all the currency was back. It shaved 2 to 3 per cent from growth, and for a longer period than anyone could have foreseen. Given this background, there ought to have been a lot of caution in proceeding with another subcontinent sized disruption. That is where political judgment, more than economic expertise alone, comes into play.

Great Analysis