New Delhi: At a time when giants like Byju’s are floundering and government scrutiny of the sector is increasing by the day, one man is waiting and watching in the wings.

India’s original education entrepreneur Arindam Chaudhuri says he is waiting for the current government to change so that he can make his comeback.

Battling multiple court cases for allegedly misleading students, evading taxes and defrauding institutions, Chaudhuri retreated from the limelight for years—leaving behind an impregnable fortress, and his foes, rivals and employees wondering about his activities.

In a recent conversation with ThePrint, he says his mission since 2014 has veered away from his first innings as India’s dream seller. He is now more interested in championing the principles of scientific thinking, rationality, and healthy living. This is Arindam Chaudhuri 2.0, and this new avatar is being minted away from the spotlight. The idea of starting a university doesn’t excite him anymore. He has moved on to the think tank race in Modi’s India with Chaudhuri’s team working for him at IIPM’s new avatar, the IIPM Think Tank.

The beleaguered Chaudhuri—once a ubiquitous face across India, splashed across billboards and front pages of newspapers—beat a slow retreat from headlines a decade ago, when the Delhi High Court restrained IIPM from offering MBA or BBA courses or advertising itself as a management and business school. Chief Justice G Rohini and Justice Rajiv Sahai Endlaw fined the institute for misleading students by claiming to be a B-school even though it had not been recognised by the AICTE or any other body. IIPM shut down in 2015, Chaudhuri’s magazine, The Sunday Indian, followed suit in 2017. Then, in 2020, he was arrested for allegedly wrongfully claiming service tax credits in the pre-GST era system.

Chaudhuri says that in 2019, all disputes with AICTE were permanently quashed in favour of IIPM.

He still maintains that this one high court judgment—on the back of a PIL filed by a competitor—was the first flick to bring down his management empire like a house of cards.

But Chaudhuri didn’t totally disappear. It’s not his style — he says he was harassed so much publicly because he always had big visibility. He says that despite a series of recent personal setbacks, he’s still upbeat about work, the transformative power of education, and his role in public life. He’s been on lecture tours, is now conducting corporate workshops, and is returning to filmmaking. At any given point in time, he’s writing between two and three books simultaneously.

“The only con I ran is that I didn’t tell students what I’d teach them as much,” says Chaudhuri, suddenly serious. He leans forward on the grey couch, knees brushing the glass coffee table in front of him, somehow unbothered by the background noise of a busy hotel lobby in South Delhi. “They were conned into thinking they were coming to learn how to have a luxurious lifestyle. Unfortunately, they ended up getting educated.”

The new strategy

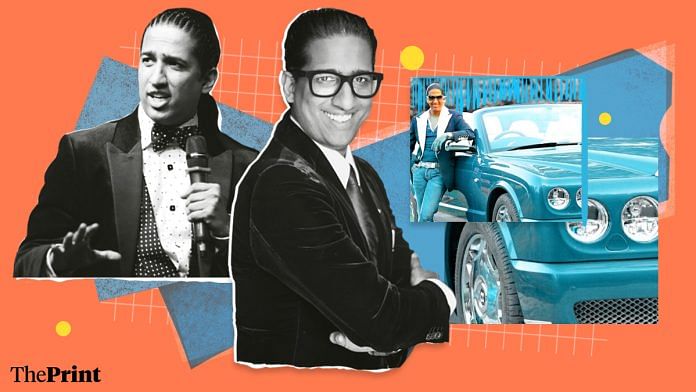

As comfortable in a hotel lobby as in his home, Chaudhuri still conducts himself with style. He’s wearing a powder blue suit with a powder blue pair of Louis Vuitton mules, glasses with blue frames, and his hair is up in his signature ponytail —higher than he used to wear it in the past, but still secured with an electric blue hair tie. When he smiles widely, a gold tooth flashes.

The only con I ran is that I didn’t tell students what I’d teach them as much. They were conned into thinking they were coming to learn how to have a luxurious lifestyle. Unfortunately, they ended up getting educated.

– Arindam Chaudhuri

He wants the world to know that he’s done with people who have preconceived notions about him—through flashy photos of him, or spurious articles by a “cabal of journalists”, or the matter of IIPM’s discreditation by the University Grants Commission and the All India Council for Technical Education. Instead, he wants people to focus on his thoughts and ideas for change. He acknowledges he had to project himself a certain way to sell his personal brand and the aspirational idea of IIPM’s management style, but his mission since 2014 has veered away from this.

Chaudhuri wants to dip his toes into education again but with a completely new philosophical twist.

His plans aren’t restricted to management, entrepreneurship, economic planning and telling his students they can achieve great things without going to an IIT or an IIM. This time, he wants to teach them something entirely new: that religion is the biggest hindrance to success. It’s become an important mission for him to champion rationality, he says, especially given the outsized role of religious extremism in India today.

“I sometimes joke that my philosophy is Bernie Sanders but my appearance is like Donald Trump,” says Chaudhuri. “My point is: listen to me. Why are you only looking at me?”

A complicated political terrain

If Chaudhuri could run IIPM differently today, he’d take a more “formal”, traditional approach.

“I was ruling at a time when you could abuse anyone, and speak out against whoever. There was no fear,” says Chaudhuri, referring to his earlier participation in television panels on politics and the economy. “I was at my aggressive peak then, I was blasting away at everyone. Today, you can’t do that.”

That was a time when the swashbuckling Chaudhuri would present his own alternative budget at the exact same time the Finance Minister was presenting the national budget in Parliament. He’d book out banquet halls and broadcast the entire event, in a grand display of confidence and expertise.

But that India is gone, according to Chaudhuri. And so has he. “Today I want to be part of the establishment,” he says.

He wants to continue to be a disruptor, but without stepping on any toes. And part of that includes lying slightly lower than he’s used to. If it weren’t for his father’s death in 2019, he would have tried to restart the entire enterprise. But then the pandemic hit, coinciding with a 14-day stint behind bars in 2020. He was arrested for making an undue claim of Central Value Added Tax (CENVAT) of service tax credit of Rs 23 crore. He made a CENVAT credit entry following a cash shortage to pay service tax, showed the amount in the next year’s balance sheets, but never paid it.

His properties in Delhi, other Indian cities and even abroad were being probed. In 2018, an indirect tax tribunal said that IIPM could not be exempt from the service tax demand as there was no scope to “exclude academic courses”.

I sometimes joke that my philosophy is Bernie Sanders but my appearance is like Donald Trump

– Arindam Chaudhuri

In yet another case, a Delhi-based institute called Institute of Marketing and Management (IMM) alleged that IIPM had stopped paying lease rent to it after entering into a management consultancy contract. While the lease dispute was going on, IMM realised that IIPM had tried to float an organisation called IIMM in 2020. An FIR filed as recently as 2023 alleges that IIPM was trying to trick potential students into joining IIMM by giving them the impression that they were being admitted to IMM.

Chaudhuri claims that the reverse of this is the truth, that IMM used IIPM’s brand to their benefit.

“You can fight, fight, fight. But you have to fight for someone, or something,” says Chaudhuri, staring into space for a moment, until the sound of squeaky shoes trudging through the hotel lobby snaps him out of his reverie.

He spent the first half of the last decade—until 2019—doing exactly that. And then the will went out of his fight. He’s spent the last five years writing, lecturing, and dabbling in films.

“Once this regime goes, I’ll get back my voice,” he says.

He used to be far more candid when IIPM was still active. At every orientation lecture, which he’d encourage students’ parents to attend, he would deliver some standard advice: the students should look forward to the IIPM experience for the education they were about to receive. But if they wanted a job out of IIPM, that’s something they would have to take up with the Prime Minister—because ensuring employment opportunities has always been the government’s prerogative.

His ultimate goal in life—encouraged by his father, Malay Chaudhuri—was to become Prime Minister of India. He says that there’s no greater service than public service to the country, and the political door, opening out onto the corridors of power, is still something he considers walking through. He says he thinks about it all the time.

And he did come close—the BJP planned on launching him in “a big way” in 2014, according to him. But it never happened.

I was ruling at a time when you could abuse anyone, and speak out against whoever. There was no fear. Today, you can’t do that.

– Arindam Chaudhuri

If he were to join politics, however, it would have to be under the party his father started—the Bharatiya Vikas Manavta Party. He would champion rationality, equality, humanism, and development for all. He doesn’t believe that any of India’s major political parties have a vision for humanity, or are thinking about human development — and so if he were to further dedicate his life to politics, it would have to be on his own terms and with his own vision.

“I can’t compromise whatever spine is left after being thrashed a lot,” Chaudhuri says firmly. “What I do is politics all the time. I want to be in politics. I don’t know when. I’m not in the mainstream yet, but hopefully one day.”

Also read: Adani controversy brings back the story of how Manmohan Singh govt rescued Satyam

A pivot in the last decade

Before things went up in flames, Chaudhuri was not only running IIPM but publishing several magazines and producing films through his umbrella organisation, Planman.

Today, it’s largely a solo enterprise. He spends most of his work time thinking, he says, but has plenty of projects bubbling away.

He’s writing a book on parenting, Make Your Own Destiny, and calculating the budget required to eradicate global poverty in a book he started with his father, The Great Global Dream. He’s also adding finishing touches to his 14th book — the first focused solely on atheism — OMG! God Doesn’t Exist.

Simultaneously, he’s working on a couple of film scripts, and says one should go on the floor soon. He plans to release a much-delayed film directed by Rituparno Ghosh, with whom Chaudhuri has made two other films—Dosar (2006) and The Last Lear (2007). Their last film together was delayed by all the lawsuits.

A cursory Google search on IIPM and Chaudhuri produces a dizzying list of controversies, confrontations, and conflicts. A more studied approach to all the lawsuits he’s involved in reveals that he’s still very much on the hook in court, for a number of cases—the most recent hearing took place in February 2024. It was an anticipatory bail hearing for Chaudhari over a medical certificate he had allegedly forged and submitted in 2016 in order to be exempted from appearing physically in court for an ongoing lawsuit against him. Incidentally, he was arrested in March 2020 for allegedly forging the same medical certificate, and the case is still in the courts.

A 2011 story in The Caravan by journalist Siddhartha Deb was one of the first—and last—long-form profiles of Chaudhuri. “He had achieved great wealth and prominence, partly by projecting an image of himself as wealthy and prominent,” Deb opens. “Yet somewhere along the way, he had also created the opposite effect, which—in spite of his best efforts—had given him a reputation as a fraud, scamster and Johnny-come-lately.”

The profile of Chaudhuri was later included in Deb’s book, The Beautiful and the Damned, published by Penguin. Shortly thereafter, Chaudhuri sued The Caravan for Rs 50 crore, also naming Penguin and Google in the lawsuit. He’d already filed similar lawsuits against other publishers, like Careers360.

My job today is to make sure that anybody who comes in touch with me questions irrationality and thinks critically.

– Arindam Chaudhuri

The article is still a thorn in Chaudhuri’s side and a court battle continues over Deb’s “blatant lies in the feedback and thoughts of the participants” of the workshop he’d attended while reporting on Chaudhuri.

But his litigiousness was also a symptom of the times: he was more willing to get his hands dirty in a pre-2014 India. His mission since then has changed, he declares.

“My job today is to make sure that anybody who comes in touch with me questions irrationality and thinks critically,” he says, while hotel staff serve green tea. “Truthfully, the idea of starting a new university today doesn’t excite me.”

And to his detractors, it might be a welcome decision. There are many who are still affected by the collapse of IIPM and Planman—from students who felt duped out of legitimate degrees to employees who went months without being paid. “The damage caused by Arindam Chaudhuri and his cohorts run deep,” posted journalist Maheshwar Peri, largely credited for spotlighting IIPM’s practices, on LinkedIn in 2023. “And I [Peri] continue to counsel such students every month, even after a decade since IIPM shut down.”

While Chaudhuri doesn’t want to set up a university from scratch again, he does want to continue teaching his philosophies.

Chaudhuri still has a team working for him at IIPM’s new avatar, the IIPM Think Tank. It forms the basis for his lecture tours and corporate workshops, which range from anything on management to communication, leadership, religion, science, and rationality. A popular theme in his workshops is comparing the leadership styles of Krishna, Mahatma Gandhi, and Prime Minister Modi. He’s got workshops coming up in Delhi and Ahmedabad and is always open to doing more.

“There were many, many things I just couldn’t foresee. It’s all a learning,” he says.

He’s focused on his own personal mission to bring about change, and is determined not to be swayed.

“If you’re a public figure, you’ll be both criticised and praised,” says Chaudhuri. “If you can’t take that, you can’t be a public figure.”

Also read: BJP spin is turning complex Delhi liquor scam into ‘drunk husbands beating wives’ issue

Life, legacy, and living forever

For a man who seemed so much larger than life, Chaudhuri is surprisingly compact in person.

His dedication to physical fitness is evident, and he devotes roughly three hours daily to exercise. He kickboxes for 90 minutes a day and never misses his one-hour walk.

He’s also interested in the idea of longevity and living forever. In a recent post on LinkedIn, he outlines his thoughts on healthcare strategies. In the future, he envisions, humans can live up to 150 years.

Chaudhuri is thinking about how he can carry his father’s legacy forward—a personal mission of his. His father was the original founder of IIPM in 1973, a legacy Chaudhuri not only inherited but also started building on when he himself enrolled. He was teaching classes on economics at IIPM even before he graduated.

He talks of euthanasia and Nordic models of governance in the same breath—how societies in countries such as Sweden, Finland, and even Switzerland further south have managed to achieve the happy balance of being developed but sustainable economies. He likens one of his theories, “happy capitalism” to the political economy of such European countries.

A perception game

Chaudhuri lives in a corner plot in a South Delhi neighbourhood. For anyone familiar with him, the house is unmistakably his. The wrought iron gates have huge ornate Cs embossed on them, and dark blue cars—a Jaguar and a Renault (the famous metallic blue Bentley, which makes guest appearances in various photoshoots and interviews, has been sold)—are parked outside, occasionally switching positions. An electric blue security guard box stands vigil, right next to a stone sculpture with different faces carved into it.

There’s no question that Chaudhuri knows how to play the perception game. It’s part of why his vision and his message reached the masses in the way they did in a pre-social media India. His aggressive marketing was a clarion call for thousands of middle-class Indians who thought they’d found a springboard for their aspirations.

“Dare to think beyond IIMs,” challenged IIPM in its famous tagline. The institution, according to Chaudhuri, offered Indians an alternative ladder to climb to the top. People no longer had to slog for years to take the beaten path towards an IIT and then an IIM to learn management and entrepreneurship when they could enrol at an IIPM and fast forward their management career.

“The word ‘MBA’ was taken door-to-door by IIPM,” says Chaudhuri, leaning forward to make his point. And there is some truth to it: his bold marketing did rejig the management landscape, telling students that they too could have a life like his and the celebrities who endorsed IIPM. Even Shah Rukh Khan was in IIPM ads.

“In India, if you’re flamboyant and seen a lot, then people are negative. Any disruptor in any country will face such issues, but in India it’s huge,” says Chaudhuri, who started using the term ‘disruptor’ to describe himself around the time it entered the popular business lexicon.

But wading through years of legal quagmire has perhaps taken its toll. He’s now on the defence, rather than offence. The youthful grin and slicked-back hair have been replaced with a more serious expression and a trend-appropriate fade underneath the signature ponytail.

I like the fact that when I enter a conference room, everyone pays more attention. It accentuates what I say. It gives me more money from the market, so to speak.

– Arindam Chaudhuri

His Bentleys have long since been sold. But he adjusts his designer outfit and makes sure to pick up his Gucci wallet off the table as he gets up.

But did anyone ever tell him he was flying too close to the sun?

Not really, he muses. “I’m good, I’m fine. I have no real attachments—I’m happy with a Bentley, and I’m also happy with a non-Bentley life. I’m happy with the way I am,” he says.

“I love getting up in the morning and dressing up,” he continues. “I like the fact that when I enter a conference room, everyone pays more attention. It accentuates what I say. It gives me more money from the market, so to speak.”

This article has been updated with Chaudhuri’s inputs regarding legal cases against him and IIPM.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)