Visakhapatnam: Rajesh, an ECG technician from Visakhapatnam, was on cloud nine as he boarded a plane to Thailand to work as a data entry operator. Back in India, the 31-year-old father’s Rs 20,000 salary wasn’t enough to sustain his growing family, and the Rs 70,000 paycheque he was promised was a lifeline. But as soon as he checked into his hotel, everything unravelled. A man grabbed him from behind, tied his arms, and muffled his screams with a handkerchief. When he woke up, he was in a rebel-controlled part of Myanmar.

Rajesh did have a new job, but it was far from what he had imagined. He had been sold to a scam call centre, forced to con other Indians online.

“Save me, father, save me,” he cried over the phone two days after he was allegedly kidnapped in February this year. This was the last time his family heard from him. Rajesh has been beaten, tortured, starved, and kept in solitary confinement, according to his family members and police. He has become a “cyber-slave”.

Rajesh’s story is all too common. Hundreds of engineering and management graduates from Visakhapatnam, or Vizag—a city that has yet to deliver on its promised tech gold rush—are getting caught in a perilous trap. Lured by shady recruiters with lucrative job offers, they leave India for countries like Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore, only to end up as unwilling foot soldiers in global human trafficking rings. And as major IT companies exit Andhra Pradesh for more business-friendly states, more young graduates are falling prey.

The Telugu region’s obsession with flying to foreign pastures began with doctors and engineers in the 1980s and grew IT wings in the 90s and beyond. This ‘Telugu boom’ created a thriving skilled diaspora but also left many vulnerable to scams, from US visa fraud to today’s Southeast Asia-based cybercrime rackets.

These jobseekers are forced to work in digital slave camps for one of the most organised, sophisticated crime operations in the world. The scam industry, which has exploded since Covid-19, rakes in up to $3 trillion every year, according to Interpol, and an organised crime ring can make as much as $50 billion annually. They run everything from honeytraps to stock market scams to FedEx frauds, making sure to target people in their own language.

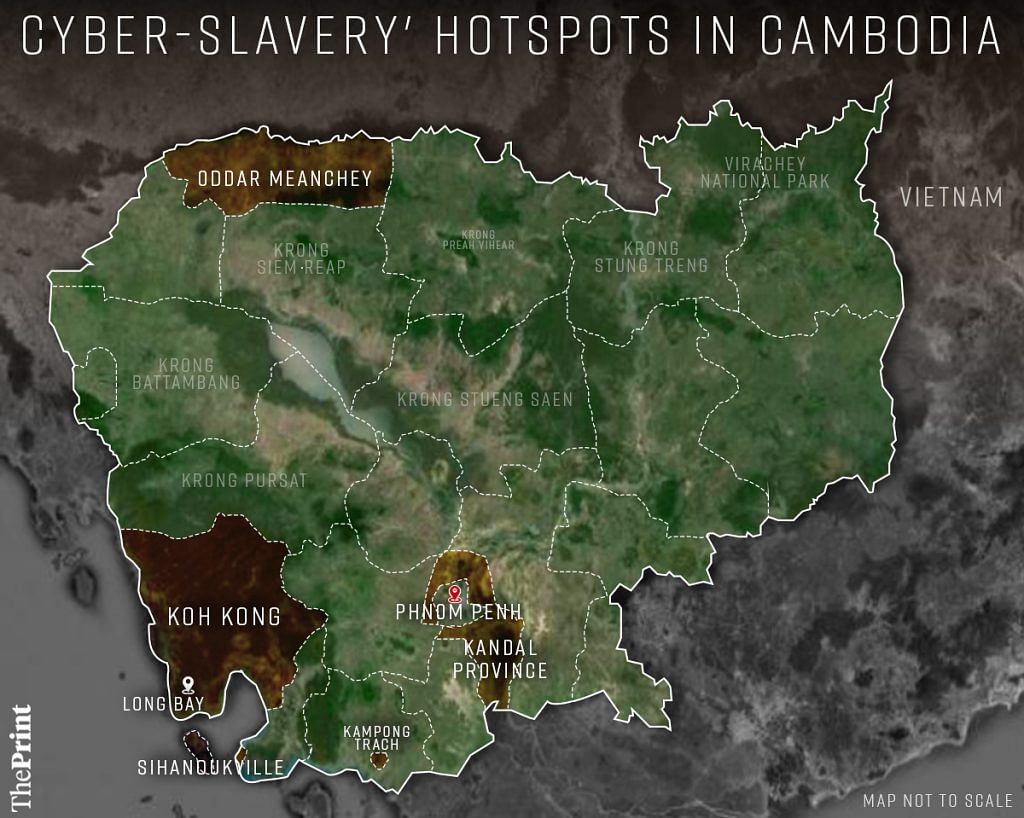

Most of the scam compounds are run by Chinese nationals, though victims also include their compatriots. Rescued Indian victims and police officials told ThePrint that people are brought into slavery for $4,000, which also becomes their price for freedom—except that most cannot afford this ransom. Such is the scale of the cyber-slavery racket that it’s been called a “global human trafficking crisis” by Interpol secretary general Jürgen Stock—and Cambodia is a major hub.

The Ministry of Home Affairs estimates that over 5,000 Indians have been forced into cyber slavery in Cambodia and the police say the bulk are from the Telugu states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Of the over Rs 1,776 crore that Indians lost to cyber scams in the first four months of 2024, nearly half were traced back to fraudulent operations in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

So far, 150 workers from Visakhapatnam have been rescued and brought back to India. While 360 Indians have been repatriated until May, many more remain in the region, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

“Gone are the days of scamsters operating from Jamtara or Nuh,” said K Fakeerappa, Joint Commissioner of Vizag Police. “As the inter-state police coordination on cracking down on scam crimes got better in India, the epicentre for running online scams shifted to Southeast Asian countries.”

In Andhra Pradesh, a huge mismatch between aspirations and available jobs is driving trained graduates into the clutches of human traffickers.

“IT jobs in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are kind of a status symbol. All young people think that they have to be an engineer and then go abroad to lead a successful life,” said Srinivas Kodali, an IT ‘hacktivist’ based in Hyderabad. “People are getting trapped in this dream.”

For well-executed scams, the bosses offered incentives to the trafficked recruits—free iPhones, drugs, invitations to in-house rave parties, and ‘dates’ with women. But those who failed to meet targets or rebelled were put through a living hell.

Also Read: Meet India’s ‘dunki influencers’. They teach you how to cross Panama jungle, Mexico border

Paying to be a prisoner

Getting a degree in Andhra Pradesh is not a problem, but landing a job that matches those qualifications is. Students claim that even MBA degrees from state universities don’t fetch salaries exceeding Rs 15,000. So, when a recruiter paints a picture of a comfortable life in a foreign country, everyone wants in. Some even spread the good word on WhatsApp groups for desperate graduates.

One such aspirant was KP Sai Mukesh, a 30-year-old from Visakhapatnam. Tall and swarthy, he’s gentle giant who seems to carry a weary weight on his shoulders. He took a leap of faith twice and crash-landed both times.

After completing his MBA from Andhra University in 2017, Mukesh wanted to work as a human resource manager but failed to find a job. In 2019, his father, a PSU employee, fell ill and had to retire, pushing Mukesh into dire straits. Then, luck seemed to shine. He applied for a job in Dubai and received an offer of Rs 70,000. He took a loan to pay for the trip, but found himself working at a shell company that paid only Rs 20,000. Disillusioned, he returned to India in three months.

It is not easy to honeytrap Indians because people are usually married. But it is easy to scam lonely Europeans and Americans, who gave crores of rupees to a stranger on the internet. The scam agents in Cambodia know this weakness

Mukesh, human trafficking victim

For years, Mukesh struggled to find a well-paying job, taking up food delivery and clerical work in factories while medical bills piled up. Then, the answer to his problem popped up on a WhatsApp group—the number of a recruiter called Chokka Rajesh who was offering placements in Cambodia for Rs 1.5 lakh.

Mukesh jumped at the chance despite having been burned once before. He paid Ch Rajesh Rs 1.5 lakh and boarded a flight to Thailand in June 2023. When he arrived, an agent picked him up and took him to Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, where a Chinese woman took charge.

After that, he was sent to a heavily guarded multi-storey compound in northern Cambodia. Several other Indians were part of the group too. The police say agent Ch Rajesh has trafficked 85 people to scam centres in Cambodia, out of which 47 are still there.

“The compound was hidden behind a huge casino. There were armed guards and the walls were equipped with barbed wire so nobody could enter or escape,” said Mukesh, who is back in his parents’ sparsely furnished three-storey home in suburban Visakhapatnam’s Gajuwaka area. “These companies were like residential societies and had everything one needed inside, from shopping malls to massage parlours to restaurants.”

At first, the towers and spacious grounds seemed impressive, but Mukesh quickly realised that his new residence was also a training institute for pulling off every kind of cyber-scam under the sun.

Hindi speakers were usually conned by Pakistani nationals who took great pride in scamming Indians, Mukesh said wryly.

Lessons in scamming

Time was not to be wasted at the Cambodian compound. As soon as arrived, Mukesh and his comrades were thrust into a rigorous 15-day training programme. The ‘curriculum’ included learning meticulously drawn scripts to honeytrap victims, persuading people to invest money, and delivering convincing responses to predictable questions from their targets.

The operations were conducted on different floors, each specialising in a specific type of scam. These floors were further divided into tables of 16 people, each led by a Chinese supervisor. Every recruit was equipped with 20 iPhones for sending messages, emails, links, and friend requests.

At the scam training school, Mukesh learned various cyber-cons and tactics. These included fraudulent stock market investments, FedEx courier fraud, TRAI and CBI impersonations, loan app scams, and honey trapping. Of these, “pig butchering” investment scams dominated the market— a type of scam named for the way targets are slowly primed and bled dry, like fattening an animal before slaughter.

“It is not easy to honeytrap Indians because people are usually married. But it is easy to scam lonely Europeans and Americans, who gave crores of rupees to a stranger on the internet. The scam agents in Cambodia know this weakness,” Mukesh said.

The companies also shared detailed databases of Indians with the recruits. These included age, contact number, gender, marital status, and profession. Frequent targets included doctors, retired army and police personnel, journalists, CEOs, and top managers.

“This is China’s cyber war against us. One we aren’t equipped to fight. The police have no training or any idea of how to stop this. Hundreds of crores are being drained out of the country on Chinese command,” Mukesh added.

The Chinese would tease us, saying the food being served was cat or dog, and they never served plain rice. The rice had cockroaches in it

-Yacob, human trafficking victim

For months, Mukesh had no choice but to comply. When he demanded to leave after realising he had not been brought to Cambodia as a data entry operator but to work as a scam caller, he was given only one impossible out.

“I was asked to pay $4,000 if I wanted to leave. That is how much the company had paid the trafficker who brought me here. That was the cost of my life,” he said.

The compound was a dubious cultural melting pot, crammed with people of numerous nationalities scamming targets all over the world. Software developers from India and African countries created sophisticated fake websites to mirror real ones. Europeans, Americans, and South Asians used their language skills to execute scams flawlessly.

People from peninsular India were central to the operation because language fluency in South Indian languages couldn’t be imported from anywhere else. Hindi speakers were usually conned by Pakistani nationals who took great pride in scamming Indians, Mukesh said wryly.

“Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, even some Nepalis just hate us. It is their way of taking ‘revenge’ from Indians,” he added.

The police confirmed the sophistication of the enterprise.

“They create exact replicas of popular stock market websites like Zerodha and Motilal Oswal, then email people with attractive subject lines. Unsuspecting people might open the link, find no faults, and end up losing lakhs of rupees,” said JCP Fakeerappa.

The subject lines of these emails included enticing claims like “stocks at lower prices” and “double your returns in 30 days.” The scammers also purposely used outdated Windows XP or Windows 7 computers to avoid detection by international law enforcement.

Vizag Police say that Indian SIM cards are being smuggled into Cambodia, fetching up to Rs 15,000 each. They have identified 24 agencies across India involved in the fake job scams, as well as 43 abroad, mostly in Dubai, Myawaddy, and Thailand.

The Vizag police have filed 12 FIRs against local recruiters under sections of the former Indian Penal Code related to human trafficking (370) and relevant sections of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

They are also reviewing the complaints of victims, such as Vizag resident Pavani Kuchibhotla. One fine day, she was added to a WhatsApp group offering investment advice and where group members posted about their profits. Initially, she traded via registered apps and found the advice sound. Then, group leaders, posing as Eltas FUD employees, urged her to use an APK for bulk trading. She downloaded the app, a mirror replica of the registered one.

“I compared both apps to be safe, but everything seemed alright,” Kuchibhotla said.

Her first investment on the fake website was Rs 25,000. Within a month, she had invested Rs 40 lakh before suspecting foul play. By then, it was too late. She had been successfully “pig butchered”.

The police confirmed that this scam originated in Cambodia. Kuchibhotla registered her case on May 12 and is holding on to hope for some refund.

However, most repatriated workers have refused to file cases. The fear of stigma and retribution stops many of them from coming forward. One of them is 22-year-old Yacob, a BTech graduate who returned to Vizag from Cambodia three months ago.

“Even though I had told reporters not to reveal my identity, my photo was splashed in newspapers. My parents are very stressed, they feel embarrassed. I’m also scared that Chinese people might do something to me for exposing them,” he said. Many of Yacob’s friends also refused to complain to the police.

Torture chambers

For well-executed scams, the bosses offered tempting incentives to the trafficked recruits—free iPhones, drugs, invitations to in-house rave parties, and ‘dates’ with women. But those who failed to meet targets or rebelled were put through a living hell.

Mukesh would report to his desk every day at 8 am sharp. He couldn’t afford to be even one second late, as that would lead to dock in pay.

His day was filled with wrenching moral conflict, calling his own countrypeople to fleece them of money. Targets sometimes called back later, pleading with him to return the money, abusing him, cursing him.

“So many times we would get calls or videos on Instagram by women cursing us that their husband died by suicide because they had been scammed of all their money,” he said.

On the company’s Telegram channel, videos would sometimes circulate of such wives—crying in front of their husband’s body hanging from a ceiling fan. The Chinese, Mukesh claimed, mocked these videos.

“I didn’t like what I was doing. But trust me, I didn’t have a choice,” he said. “Even if I felt bad for someone and wanted to tell them to cut the call even as they were falling into my trap, I couldn’t do it. My phone was on constant surveillance, and our handlers would use translation software to monitor what we were saying.”

Mukesh claimed he was beaten and tortured for deliberately not meeting his targets on certain days. The price of rebellion included beatings with baseball bats, electric shocks through tasers on the head, or being denied food for days.

Isolation in a dark room was another tactic—and Mukesh claimed to have endured a week of it.

“I couldn’t see, I couldn’t think, I couldn’t say anything. Whoever went into the dark room came out a different person,” he said.

For the Indians, the food was inedible. They didn’t know what meat they were eating but were confident it wasn’t chicken or mutton. Often, they went hungry because pork or beef was served. Other times, they made peace with eating frogs.

“The Chinese would tease us, saying the food being served was cat or dog, and they never served plain rice. The rice had cockroaches in it,” said Yacob.

So far, only two women from Visakhapatnam have been rescued from the scam call centres. Their plight of recruited women was even worse as they were allegedly forced to strip at gunpoint on video calls. Police say women at the centre were also harassed and sexually abused.

What finally broke the silence and brought the shadowy compounds of Cambodia to the limelight in Andhra Pradesh was the resolve of an ex-Navy man who refused to con people even at gunpoint. After returning to Visakhapatnam last year, he fought for months to register a case that triggered police action and caught the government’s attention. And then came a full-fledged rebellion.

Revolt and rescue

Botcha Shankar, a 40-year-old retired navy man, roams around Visakhapatnam in a Nissan Micra with a light brown briefcase filled with multiple copies of his resume.

A tall, heavyset man with a commanding manner, Shankar has been out of a job ever since he quit the navy in 2018. A trained firefighter and technician from the Industrial Training Institute, he has searched for jobs in companies and dockyards, only to be turned away. Even job postings on groups for armed forces veterans have not borne fruit.

“Wherever I go, they ask for recommendations. Even if I arrange it, it doesn’t work, because nepotism is the only way one can get a job in Vizag,” he said wearily.

In May 2023, he finally got a job offer in Singapore, but instead landed up at a Chinese-run call centre in Cambodia. When he found out what was going on, he refused to participate in the scam. And unlike most other recruits, he wasn’t easily intimidated. Even beatings, torture, and weeks in isolation didn’t break him. His navy training helped, he said, showing off scars on his arm that are still reminders of the ordeal.

All along, Shankar plotted his escape. Last November, he put his plan into play while the company’s personnel were busy partying at night. He knew where his passport was, grabbed it, and by 3 am, he had crossed the barbed-wire wall to safety. With the help of a local shopkeeper, he booked a cab to Phnom Penh. There, he bought a cheap handset, booked flight tickets, and flew to Bangkok. From Bangkok, he flew to Kolkata and finally to Visakhapatnam.

Returning to safety was just the beginning for Shankar. Once home, he sought justice. For about four months, he and his wife drove 20-25 kilometres every day to the cyber crime branch to get his case registered, but to little avail. The police personnel he met, he said, were unwilling to register his complaint until more senior officers stepped in.

I will work as a gardener, guard, anything. But now I won’t go to a poor country, I will go to Australia or New Zealand. I want to create a secure future for my kid

-Botcha Shankar, escapee from Cambodian ‘slave’ camp

After fighting tooth and nail, Shankar’s complaint was finally registered in March 2024, after which the former commissioner of Vizag police issued a video statement urging people stuck in Cambodia to contact the police for help in returning to India.

On 18 May, the Vizag police arrested three recruiters, including Chokka Rajesh, who had trafficked both Mukesh and Shankar. They were booked under various charges, including human trafficking, extortion, criminal conspiracy, and wrongful confinement.

News of Rajesh’s arrest and the escape of one of the cyber slaves spread like wildfire, giving the scam compound workers in Cambodia confidence that the government would back them. On 20 May, 300 such Indians working in Sihanoukville— a coastal township with a famously deep and damaging Chinese footprint—started a rebellion. Among them were 150 Indians from Visakhapatnam, including Yacob.

“I thought I would die there in Cambodia,” Yacob said. “Hundreds of us shattered the glass of cars, set fire to them. The facility bosses escaped and we were arrested by the military police. After the intervention of the Indian embassy, we were released and repatriated to India.”

After@vizagcitypolice

successfully unraveled the human trafficking network in commission of #cybercrime operating from #cambodia,yesterday hundreds of youths trafficked from India more particularly from #vizag revolted against their handlers in Cambodia@APPOLICE100 (1/2) pic.twitter.com/wJFVtOTJOo

— VizagCityPolice (@vizagcitypolice) May 21, 2024

But thousands of other Indians are still in Cambodia, many among them trapped against their will. And given Cambodia’s deepening ties with China, these labour camps largely function with impunity. Reports also claim that some scam compounds have links with the Cambodian royal family, so no effective action is taken against them.

For now, the Indian government has issued various directives cautioning people against taking up jobs in Cambodia and other countries. The Indian embassy in Cambodia has also started a helpline for those seeking to return.

Back home, the police have enlisted KP Mukesh for help. He has conducted workshops across police stations in Vizag district on the criminal modus operandi of the cyber-crime mafia.

The next challenge, police officials say, is to monitor the recruits who were rescued and brought back to India.

Also Read: ‘Israel is a strong country, Indians will be safe there’ — Haryana workers storm job drive

Returned, but restless

There’s a new worry rippling through Vizag’s police stations. Many repatriated Indians are now untraceable, and the fear is that they might start their own sophisticated criminal rings in India, using their newfound cyber-scam skills.

There may be nothing else for them to do. Jobs are still scarce and the glass buildings of Vizag’s IT Park bear a deserted look, like an abandoned castle of glass.

For Mukesh and Shankar, becoming scamsters in India is not an option. But the desire for a foreign job has still not left them.

Shankar is running out of resume printouts but no one in Vizag has shown serious interest in hiring him yet.

“I will work as a gardener, guard, anything. But now I won’t go to a poor country, I will go to Australia or New Zealand. I want to create a secure future for my kid,” he said.

Mukesh hopes to get another shot at working in Dubai, this time at a genuine company. Until then, he bides his time. His mother offers prayers to Sai Baba while he watches motivational videos of influencer BeerBiceps on the living room sofa. He is a fan of podcasts, taking notes from successful people about their mantras.

His own refrain is one that he’s been repeating since his graduation seven years ago: “I need to clear my loans, but I can’t find a job in Vizag.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Interesting article but framing is quite biased against China as if cybercrime is some national policy. One could go by the same logic and blame BJP and state of Gujarat for all the call center scams which prey on the elderly in the US.

Those cybercrime camps are run by Chinese and Cambodian gangsters and many Chinese are also kept as slaves. I sympathize with the Indian slave victims but framing Pakistani, Nepali and Bangladeshi slaves as inherently enjoying scamming yet Indian scammers are just unwitting victims seems a bit disingenuous.