Kota: Hundreds of people in Kota are racing against time to meet a deadline that has nothing to do with test scores, exams or coaching institutes.

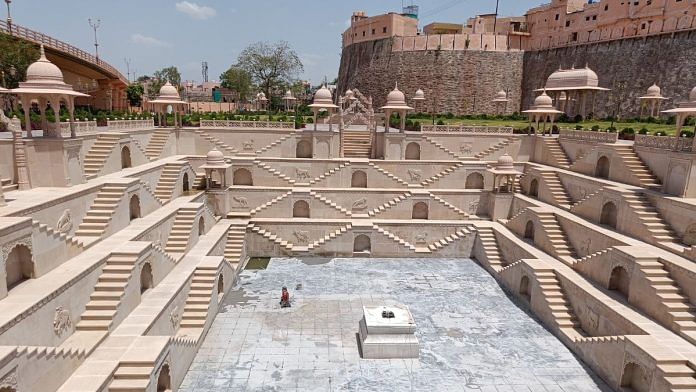

Labourers have been toiling for three years to turn the stress-infested education hub of Kota, Rajasthan, into a touristy city and give its residents a new walking promenade and a riverfront vista. The grand Chambal riverfront, with dozens of ornate pillars, 8 archways, 22 ghats, and fountains is the makeover that few in Kota imagined.

It has transformed smart city Kota’s mood. There are green signposts everywhere leading up to the much-anticipated 3-km-long Chambal riverfront. The façade of row houses now sport a new-old look – with Rajasthani chhatri architectural style in Dholpur stones. Hoardings loudly declare that Kota will now be beyond comparison, as the education city will also become a tourist city.

“We have tried to make a model city and completed the riverfront in record time. We are sure that people from all over the world will come to see it,” said Kamal Meena, an official from the Urban Improvement Trust (UIT), Rajasthan’s statutory body that serves as the nodal agency for the project. Meena, however, claimed that some people do not like the city’s development. “The lobby is opposing the riverfront because it is unable to see its potential,” he said.

The Rs 1,200-crore Chambal riverfront is the latest in a series of aspirational river renewal projects that has captured India’s urban imagination in the past decade or so. Indian cities have gone through other cycles – every city wanted a mall in the early 2000s, then came the race to build Metros. Now it is the riverfront rush. And it all began with the ambitious but contentious Sabarmati riverfront during Narendra Modi’s tenure as Gujarat’s chief minister. Since then, over a dozen riverfront projects have come up – Gomti, Jhelum, Mula-Mutha, Saryu, Brahmaputra, Alaknanda, Tapi, and Musi being some. Each one is bigger and grander than the last. It holds out the promise of the new middle-class urbanity that has escaped Indian cities for long.

Unlike the West, Indian city planners have largely ignored the rivers, which have, over time, become more polluted and littered – with people often using them for bathing, washing, and defecation.

Kota is set to have the mother of all riverfronts. It will have theme-based ghats – Sahitya Ghat, Bal Ghat, Hadoti Ghat; a 40-metre-high Chambal mata statue; second-largest musical fountain after Barcelona’s Magic Fountain of Montjuïc; largest statue of Maharana Pratap in Rajasthan; and the world’s largest bell, weighing 82,000 kg.

And it has a unique look-out point too. Through the eyes of Jawaharlal Nehru. A large metal face of India’s first prime minister has eye holes that visitors can peek through at the river.

Kota’s makeover push

In the scorching heat of June, 42-year-old Sitaram and 25-year-old Ramlakhan tirelessly grind the famous Dholpur stones with a spade and flagon. One only hears the sound of machines and tools these days. Ramlakhan spends his days carving stones with a chisel and hammer, his body covered in layers of dust and a handkerchief shielding his face. “We have to work day and night because it (the riverfront) has to be completed in time,” he said.

The Chambal riverfront has already missed several deadlines, including March 2022, December 2022, March 2023, and the most recent target of May. Now, the authorities want to finish it by the end of July and invite Congress leader Rahul Gandhi for the grand opening, coinciding with the buzz around the upcoming assembly election in Rajasthan.

Kota, Rajasthan’s high-stress pressure-cooker city with frequent news of student suicides, attracts more than two lakh students every year for coaching purposes. The entire cityscape is adorned with posters advertising various coaching institutes. Over the past three years, Kota has been attempting a makeover unlike any other. It got rid of all traffic lights to bring about seamless commuting experience, installed beautiful royal citylights, magnificent Chaurahas (intersections), U-shaped flyovers, Helical clover bridge, and statues of Gandhi-Nehru-Patel to showcase the city’s blend of history and the modern smart city with a tagline: Sundar Sugam Kota.

The Chambal riverfront adds to the city’s beauty exemplified by the famous Seven Wonders park, sculpture of floating horses on the Kishore Sagar Lake, Chambal garden, and city park, which has a fancy new Oxyzone park. Roads have been beautified by creating the Longewala victory scene at the Antaghar Circle, paying tribute to Indian soldiers. There are new sewer lines, greenery on both sides of the streets, small parks along the roads, and a prominent statue of Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi — the latter depicted with a computer in his hand.

“The goal is to make Kota a tourist spot,” said Mahavir Singh Meena, the city’s senior town planner. “Tourism is one of the main sources of revenue generation today. This riverfront will surprise everyone,” he said, reciting a famous Sanskrit shloka to describe the riverfront: ‘Na Bhuto Na Bhavishyati (such a thing has never been made before and will never be made in the future)’.

The Chambal River pierces through Kota city, which was part of the Bundi’s Rajput kingdom. The city with its numerous chhatris and palaces never really got the tourism tag that other big Rajasthani cities did. Now, in a renewed push to turn smart, new malls, hotels and roads have been constructed. The Chambal riverfront will be Kota’s crown jewel.

“95% of the work has been completed. Before the riverfront, this place was in bad condition, but it has now been turned into a paradise,” Meena said. “There is no riverfront like this in the whole world,” added the executive engineer. Earlier, drain water from the surrounding settlements used to flow into the river and there was garbage all around. On the river beds, there were huge stones that have now been levelled.

Kota planners hope that their riverfront will also become the most-visited, selfies and Reels spot much like Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati riverfront, inaugurated in 2012. The latter is now part of PM Modi’s politics of visual theatre and grandness. It had become a backdrop during the dinner hosted by Modi for Chinese President XI Jinping, the boarding of a sea-plane during the 2017 Gujarat election, the celebration of MK Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary, and also a part of Modi’s 2014 Lok Sabha election campaign.

India’s neighbour Pakistan has also been trying to build a riverfront on the Ravi river in Lahore for a decade. In 2014, then-PM Nawaz Sharif had sent a team to India to see the Sabarmati riverfront.

“The Riverfront Development (RFD) idea, which is currently being pushed by the central government in multiple cities, is essentially a copy-paste of Sabarmati riverfront development,” said Priyadarshini Karve, the convener of the Indian Network of Ethics and Climate Change (NECC).

“The project aims to…redefine an identity of Ahmedabad around the river. The project looks to reconnect the city with the river and positively transform the neglected aspects of the riverfront,” states the Sabarmati riverfront website.

Also read: Private universities must offer urban planning courses if Indian cities are to be rescued

Out of the view

Kota’s Chambal riverfront, designed by architect Anoop Bartaria, is the dream project of Shanti Dhariwal, the MLA from Kota North and the Urban Development and Housing Department minister in the Ashok Gehlot government, whose aim is to save Kota from floods and put it on the tourism map. India’s riverfront projects have multiple goals – from tourism to walkable public space to religious revival. Every river has religious folklores built around it over centuries – Saryu, Gomti, Ganga, Sangam, Alaknanda — but in recent decades, the cities’ intimate connect with the water bodies lay broken. Minister Dhariwal even said that the Gehlot government can hold its cabinet meeting at the riverfront.

Ravindra Tyagi, former chairman of UIT, said that the banks of the Chambal were unused and in a dilapidated condition. “With the construction of the Chambal riverfront, the surrounding settlements will also be safe. Kota is being discussed everywhere. Something unique and unforgettable is being created. In a way, it is a gift to the country,” he said. The riverfront, he added, will be a buzzy people-friendly place with cafes, handicraft bazaars, music, and miniatures of many important monuments.

Many homes along the riverfront have been relocated to a better site in the city to Nanta area, about 5 km away. But there are some who lived on the other side of the river, away from the riverfront façade. These are mostly families of poor Muslim labourers, alongside those in government jobs as well as some engaged in skilled labour. All of them have lost their direct line of sight to the Chambal.

“We have been denied the spiritual attachment we had with the river. Earlier, we could go near the river anytime, and had access to pure air, but the government has built walls, blocking our access to the river,” said Mohammaddin, a resident of Ladpura locality just behind the riverfront. The walls are so big that they block the sunlight, making the localities dark several hours before sunset. The government has shut all the paths that connect these neighbourhoods to the river.

UIT has entrusted documentary filmmaker Rahul Sood with the task of making a promotional video for the Chambal riverfront. “These days, I’m capturing the beauty of the riverfront through multiple cameras and drones. The film will be released next month. This is a very beautiful site for shooting,” he said.

On 3 July, minister Dhariwal posted a two-minute video made by Sood’s team capturing the panoramic view of Choti Samadh and Badi Samadh, a religious place along the riverfront. “The world’s first heritage riverfront is going to become a big centre of spirituality as well,” Dhariwal captioned the video posted on Facebook.

“Money is being spent like water on this project,” BJP’s Kota South MLA Sandeep Sharma said.

The Chambal riverfront is India’s first to be built near a dam. Environmentalists say this threatens the Chambal river because the waters becomes ferocious when released from the dam during heavy rains. Sudhir Gupta, a wildlife conservationist from Kota, said the cement structures being built will hurt the riverbed.

UIT officials, however, have dismissed any concerns regarding the safety of the riverfront project. Meena said the officials from Kota Barrage helped with the project design, and the structures have been constructed taking into account the river’s velocity. He added that there won’t be any significant damage to the structures, although minor destruction may occur in the future.

Brijesh Vijayvargiya, the convenor of Chambal Parliament working on issues related to the Chambal river for the past two decades, said that the oxygen level (BOD) in the river has reduced considerably. “Chambal river is in ICU. Instead of treating it, cosmetic surgery is being done by making a riverfront,” he said.

Also read: From ‘open sewer’ to ‘success story’ — how K-100 became Bengaluru’s ‘model’ stormwater drain

A nationwide ripple

The environmental concerns notwithstanding, the image makeover is something that Kota desperately needs. In recent decades, the city’s reputation as a coaching hub for hyper-competitive examinations has given it the tag of a high-pressure laboratory of super-ambitious students. There has also been a spectre of rising student suicides, with 16 deaths in 2023, including nine in May and June alone. Tyagi, the former UIT chairman, says the riverfront will act as a stress-buster for students by giving them an open space to walk about. The UIT estimates around 1,500 visitors daily.

These riverfront redevelopments are not just vanity projects; they align with PM Modi’s urban vision. In 2021, the Jal Shakti ministry launched an ambitious River Cities Alliance, providing a platform for sustainable management of urban rivers in India. Modi’s flagship project — the spectacular redevelopment of Kashi (Varanasi) by architect Bimal Patel inaugurated in 2021 — was also a part of his drive to reimagine the city’s relationship with the Ganga River. Riverfront projects are not merely about beautification; they serve a practical purpose as well, the government had said in Lok Sabha.

Several riverfront projects are planned or underway across India, including in Uttar Pradesh, where proposals for the Saryu, Prayagraj, Hindon, Yamuna (Vrindavan), and Ganga (Kanpur) riverfronts are being considered. In May this year, the foundation stone for a riverfront project in Simariya Dham, a religious centre in Bihar, was laid by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar. Pune’s Mula-Mutha riverfront is being developed by Bimal Patel’s company, HCP Design, which has also worked on the Central Vista, Kashi Vishwanath Corridor, and Sabarmati riverfront projects. Patel is regarded as a go-to architect for Modi’s ambitious projects.

However, some riverfront projects face challenges. The Yamuna riverfront project in Vrindavan has been stalled due to concerns raised by the NGT regarding environmental violations. The Odisha government’s ambitious Bali Jatra riverfront project in Cuttack has also not progressed due to objections over construction on reclaimed land in the floodplain zone, according to NGT chairperson AK Goel.

The Modi government has recognised the commercial potential of rivers and aims to develop 23 river systems for freight and passenger vessel transit, promoting the use of inland waterways as a cost-effective means of transportation. The National Waterways Bill 2015 was passed to develop 111 rivers across the country, tapping into their historical significance and potential for modern India.

The high-level committee on urban planning, formed by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, has recommended more riverfront projects across the country. It has identified 25 cities that should receive funding to rejuvenate their respective riverfronts.

Riverfront projects now feature in boastful election campaign achievements too, and are also embroiled in corruption blame-game. The Gomti riverfront project in Lucknow, initiated by the Akhilesh Yadav government, is currently under investigation by the CBI. An anonymous official previously involved with the Gomti riverfront project said that the Lucknow Development Authority’s request for the No Objection Certificate (NOC) for the beautification of the riverfront has been delayed due to the CBI investigation.

Similarly, the Dravyavati riverfront project in Rajasthan, inaugurated by the Vasundhara Raje government in 2018, has faced neglect and deterioration under the new administration. Raje has emphasised that riverfront projects should be approached from the perspective of public interest rather than through a political lens.

The Brahmaputra riverfront project was conceived under the Smart City mission, launched by PM Modi in 2015, while last month, Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha inaugurated the Jhelum riverfront in Srinagar. Under Delhi’s makeover plan, LG VK Saxena has emphasised on developing more eco-friendly places, with plans to develop the Yamuna riverfront along the lines of Sabarmati riverfront.

Also read: How urban planning can make Indian cities more inclusive for women

Riverfront or river rejuvenation?

Just like environmentalists opposed the Sabarmati riverfront project over concerns about riverbed erosion and decreased water flow speed, new riverfront projects are also being besieged with petitions and criticism.

“We have to understand that rivers are for teerthatan (pilgrimage) and not for paryatan (tourism). We call rivers mai (mother), then why are we busy in kamai (earning money) from them?” said Rajendra Singh, an environmentalist who is known as the waterman.

But the riverfront revolution in India is now unstoppable. The sheer visual spectacle of these projects are bedazzling for the country’s urban middle class. Kota residents say they are excited about taking their families for leisurely strolls along the riverfront, and dream of witnessing their city put on the global tourism map.

While the labourers from Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan work tirelessly day and night to create what is envisioned as the world’s most beautiful riverfront, they themselves rarely get the opportunity to witness its grandeur. But their children have grown up in amidst the adverse conditions of the riverfront construction over the past three years. They aspire to return to this place where their parents have dedicated their skills and artistry, putting their blood and sweat into crafting the most beautiful artwork in riverside history.

In the scorching heat of June, as the clock strikes one in the afternoon, hundreds of labourers working on the riverfront set aside their tools and seek shade along the cemented riverbank. Men and women, carrying their children on their shoulders and tiffin boxes in hand, can be seen from afar. Despite the fatigue, there is a sense of relief on everyone’s face—a contentment from having earned their mehnat ki roti.

(Edited by Prashant)