A lot can be said about what the system lacks, but how do we address the issues of those who enter the workforce with a degree in urban planning? Who hires them, at what wages, and who do they compete with? The answer lies in the conspicuous absence of the private sector in urban planning education and the urban planning process. Only a few private universities offer courses in urban planning. Urban local bodies don’t get to make plans and state governments do not mandate the filling of vacant urban planning positions. This takes away the employability of urban planners. We need the presence of the private sector on both demand and supply sides. Scholar-practitioners such as architect Bimal Patel are big champions of this change, as we shall see below.

We need the private sector to offer urban planning courses to meet requirements and reorient education. The presence of private universities creates scale and modernization in education, as it would in any sector. The fields of engineering and management saw the quality of graduates and post-graduates soar in response to demand. Institutions that matched global skills were created to meet this demand and their graduates helped raise the standards of Indian industry. Likewise, as soon as ULBs are mandated to undertake town planning, they will work with the private sector to draft such plans (hopefully this exercise will be different from when, under JNNURM, the drafting of city development plans was outsourced to consulting firms). Once this happens, more institutes will enter the urbanplanning education space and the standards and competitiveness of the urban planning industry are both bound to go up. In such an environment, urban planners will be able to focus on elements of equity, informality, transport, energy consumption, and the dynamic role of the private sector.

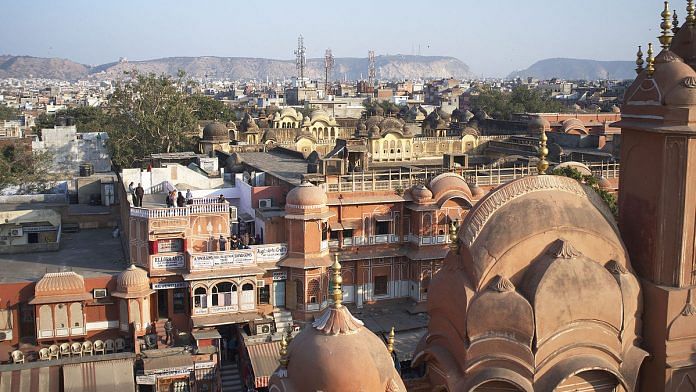

This change is much desired, as by 2031 India will have eighty-seven urban agglomerations with more than a million people (metropolitan areas), up from fifty-three in 2011 (Ahluwalia, 2019a). Growth in metropolitan areas reflects the changing nature of the economic structure in India, its transition from an agrarian economy to a servicebased economy, with the largest share of people engaged in the informal economy. The metropolitan planning committee was envisaged as a channel for development of urban agglomerations with a million-plus population, and it would have elected representatives as members.

Unfortunately, even in those areas (not many) where metropolitan planning committees do exist, they have not been empowered to work on a development plan for their metropolitan region (ibid.).

Thus far, planning has failed to deliver on the emerging role of the private sector and the informal economy. The city that best shows up this lack is Gurugram (formerly Gurgaon) located in Haryana on the that state’s border with Delhi. At the beginning of the 1970s, Gurugram was largely a rural agricultural district, when some land was taken over by Sanjay Gandhi for his start-up venture ‘Maruti’—a manufacturing plant for a small indigenous car. From that start Gurgaon/Gurugram has grown into a ‘Millennium City’, serving the aspirations of a growing economy, hosting the headquarters of the world’s biggest companies, business-process and knowledge-process organizations, alongside roadside eateries and exclusive clubs that buzz with activity through the night.

Over the years many agricultural landowners in Gurugram have become millionaires overnight,their land bought at relatively exorbitant rates by real estate developers and by people who earned generous salaries. The city has worked round the clock to emerge as a residential and business counter-magnet to Delhi. The nightmarish traffic snarls on National Highway (NH) 24 from Delhi to Gurgaon, has not stopped people from commuting to and from the city. And guess what? Gurgaon never had a Master Plan till 2007, and by 2015, it was already wellestablished in its present avatar and earning close to half of Haryana’s

annual tax revenue—INR 16,500 crore (Narayan, 2015).

Could the lack of a master plan explain the city’s (haphazard) survival? Private-sector solutions to public failures in areas such as drinking water, electricity, safety, transport and so on, have saved the city and led it to thrive—I guess the absence of a master plan had to

reflect somewhere. Indian cities have the option of collaborating with private players to plan well and see how the market, particularly the labour market, is functioning. As discussed previously, the movement of people is crucial for the success of cities, which are economic entities. Thanks to initiatives like Smart Cities and the world’s overall transition

to data and evidence-based policymaking, the cities are in a position to adapt in real-time. ‘Movement’, a website created by Uber, provides historical insights on a range of key indicators including travel duration, vehicle movement, route details and new transit-ways, among others (Balantrapu, 2017). The primary intention of this website is to assist officials with better city planning. By 2017 Uber had driven over 2 billon trips in 545 cities in 66 countries (ibid.). Given that the website (movement.uber.com) provides historical anonymized data for all days and all hours in the day, it’s a goldmine for urban planners.

Data from Uber and similar service provider Ola can be as creatively used as our imagination. In association with other city data, city planners can use simulation from this actual data to identify the changing landscape of cities, the clustering of economic activities, bottlenecks and opportunities in urban transport, priority choke points for movement of people, and the impact of key events. These data insights and analytics can be used by urban planners for continuously improving the quality of life of citizens and ensuring efficient utilization of resources. The data can help them run experiments or study the impact of key policy changes at the city level—the impact of a new flyover, congestion at certain hours, launching a new bus service or route, changing land use, or liberalizing FAR in a market area, and so on.

This excerpt from Devashish Dhar’s India’s Blind Spot has been published with permission from HarperCollins.

This excerpt from Devashish Dhar’s India’s Blind Spot has been published with permission from HarperCollins.