Lucknow: Shayara Khan spent her childhood in Lucknow without knowing the joy of playing outside in the evening. It was a pleasure her family patriarchs reserved for male members and it never even occurred to her to ask for permission. It wasn’t until she was 20 that Shayara finally got to join the mixed group of Hindu and Muslim girls playing badminton and stapoo in the colony’s narrow gullies. With her father’s blessings, she donned her headscarf, wore chappals, and joined the fun and games. She calls it the best day of her life.

The 22-year-old says she owes this newfound freedom to “badi ma’am”— retired Lucknow University philosophy professor Roop Rekha Verma. “She spoke to me and my family constantly about gender equality. Now my father understands,” said Shayara, primary caretaker for her four siblings since her mother’s death. “I have friends now. Even male friends, Hindu friends! She has opened up my world.”

Verma is the opposite of the cliché of ivory-tower academic. She is Uttar Pradesh’s philosopher-pamphleteer. For four decades now, she has taken abstract philosophical concepts like equality, freedom, justice to the streets. Literally. She defies boxes. Calling her a professor doesn’t quite cover her oeuvre, and describing her as an activist is reductive. She is a powerhouse combo of ideas, ideology and ideals and has earned formidable foes, be it former vice chancellors in Lucknow University who ran a campaign against her in the 1990s, to members of the RSS, whose ideology she condemns.

In 2022, she gained nationwide attention after she joined the Supreme Court petition against the remission granted to Bilkis Bano’s rapists. Verma says she never met Bano, but she “wanted to do something” about the injustice, and so she did. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court set aside the remission.

I was never against the building of a Ram mandir. I was against the communal hatred that was engulfing the country.

Before this, when no one else dared step forward, Verma volunteered to be the bail guarantor for Siddique Kappan, the Kerala journalist jailed under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) while reporting on the controversial Hathras rape case.

Even at the age of 80, the Gandhian’s sprightly sari-clad form can still sometimes be seen on roads, handing out pamphlets on communal harmony. A 2022 video of her in action even went viral, but she’s been doing this much longer.

The idea of putting progressive thoughts on paper for the public came to her in the 1980s, as a counter to growing tide of divisive politics. “Ever since I read or heard about the independence movement, I was convinced that creating public awareness is the only way we can continue the idea of India. I am not a politician, bureaucrat, or policeman to bring changes in society… as ordinary citizens our only power is engaging with the public,” Verma said, speaking to ThePrint at the office of her NGO Saajhi Duniya (Shared World) in Lucknow.

While it may be tempting to pigeon-hole her as a typical liberal activist, Verma said the problem of Indian leftism has been the use of jargon and language that alienates everyday people. “You just can’t walk into a village and tell women there that from tomorrow they have to completely suspend how they live and agitate against the patriarchy,” she noted. “No! One has to understand her issues, and tell her about the principles of equality in a different way.”

Whether she’s knocking on car windows in heavy traffic or braving legal mazes, Verma has always prioritised her principles over the tyranny of ‘respectability’, freeing others of constraints along the way.

Also Read: Mahasweta Devi–the crusader, activist, writer who fought for the oppressed

Ram temple, rapists, ‘respectability’

From the Ram temple fanfare to the feting of the Bilkis Bano rape convicts, Verma refuses to be swept along with the tide or ignore festering undercurrents. ‘Troublemaker’ is a label she wears with pride.

Amid the razzmatazz and ahistorical media frenzy surrounding the Ram temple consecration, she lamented the loss of popular secular sentiment in Modi’s India.

“Not only have frictional discourses increased, their acceptance has also increased,” she said. “When parliamentarians say things like ‘goli maaro saalo ko’, or a Muslim MP is referred to with a slur in Parliament, the general public also feels emboldened to say ideological things.”

Coming of age in a young India scarred by poverty, Partition, and the struggle for a secular identity, Verma’s values were shaped by the turbulent times and a reading list packed with progressive literature.

In the 1980s, when the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s campaign for the Ram temple in Ayodhya was gaining momentum, her instinctive response was fear.

“I was never against the building of a Ram mandir. I was against the communal hatred that was engulfing the country. I have grown up fearing Partition, fearing that this kind of communal hatred would grip the country again and divide society on religious lines,” she said.

But wallowing in despair wasn’t an option for her. As a young academic she knew she could only do one thing to bring change: talk to people.

“At the end of the day, any change comes from the ground. Researchers have to step outside, journalists have to indulge the public to get to know their grievances. Everything begins there. So I thought I should be generating awareness among the people about communal harmony,” she said.

Sharing her thoughts with others sometimes drew ridicule and abuse, but she also encountered open minds.

“During this time, I did meet people who were completely unwilling to hear what I had to say, but mostly I met tolerant people, eager to listen, to even change.”

Nobody joined me in distributing these pamphlets because nobody considered it a respectable thing to stand on the streets like that.

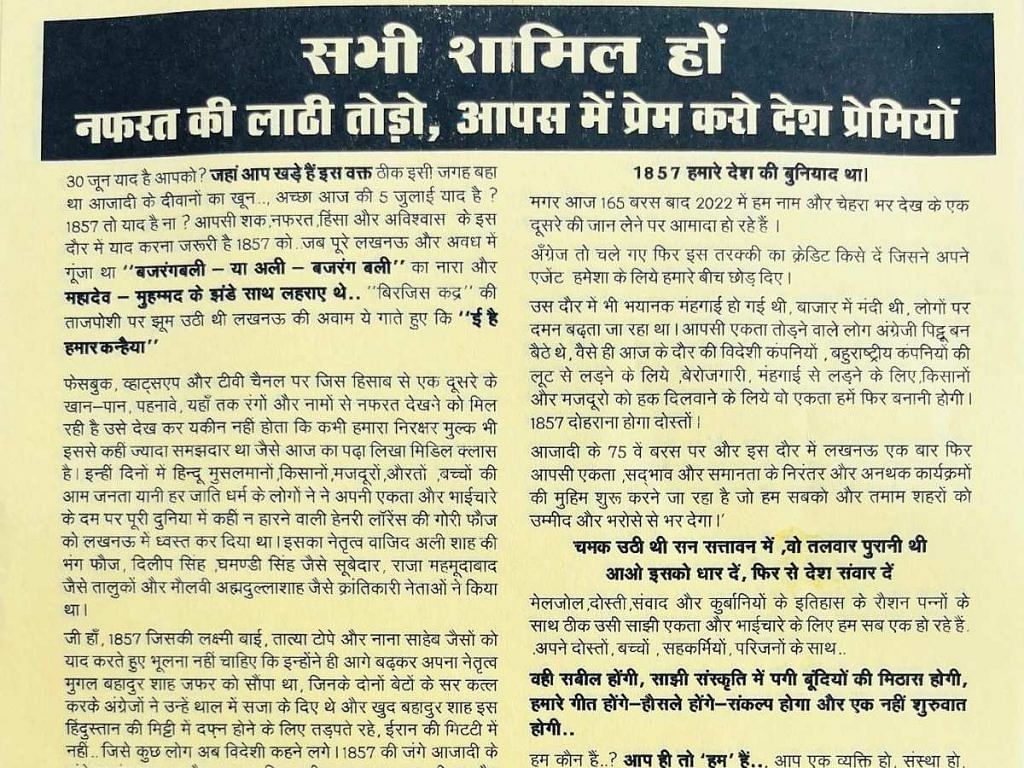

She then started writing pamphlets about Hindu-Muslim unity, the principles of India’s freedom fighters, and secular thought, printing them at the university press before distributing them on street corners herself.

“I never had a eureka moment. It just happened organically,” Verma said. One pamphlet highlighted India’s collective history of unity and its positive impact on the nation’s progress, she recalled. Another described how two leaders, one Hindu and one Muslim, emerged triumphant after a conflict with British soldiers in Lucknow’s Chinhat area in 1857.

But not only did this activism turn out to be a lonely endeavour, it also earned Verma the ire of her superiors at work.

“Nobody joined me in distributing these pamphlets because nobody considered it a respectable thing to stand on the streets like that. University teachers would gossip about me and how I was just found standing on street corners,” she said. “The then vice chancellor even called me to his office once and scolded me, saying this wasn’t a respectable thing to do, especially for a teacher.”

Verma listened to whatever the VC had to say, but took none of it seriously—she was confident in herself.

The same courage of conviction led her to join a Supreme Court petition against the remission granted to the 11 men convicted of raping Bilkis Bano during the 2002 Gujarat riots. At the time she noted that standing with rapists and murderers is “the highest form of obscenity in a democracy”.

The news of remission (to the Bilkis Bano rapists) came as a shock to me, I couldn’t believe such injustice could happen in India

Verma described why she was deeply shaken by the case. “I have worked with many victims of the 2002 Gujarat riots, though not Bilkis Bano. Her case is among the worst atrocities that took place at that time. The news of remission came as a shock to me, I couldn’t believe such injustice could happen in India,” she said. The convicts’ multiple furloughs and paroles and the celebratory welcome they received upon release “numbed my mind,” she added.

Verma also took a stand for Siddique Kappan, a journalist from Kerala jailed in Uttar Pradesh under the anti-terror law UAPA in October 2020. Though granted bail by the Supreme Court in 2021, Kappan remained imprisoned due to the difficulty of finding UP residents willing to stand surety for him, a condition for his release. Without hesitation, Verma stepped forward. The charges seemed “suspicious” to her and she wanted to extend some “small help”.

Rather than proselytising, Verma’s NGO Saajhi Duniya strives to bring change within communities by way of street plays and public discussions.

Dialogue for change, ‘but today nobody likes criticism’

Across town from the pristine Gomti riverfront park, Lucknow’s Indira Nagar is a colony of open drains where human faeces can be seen flowing freely. It’s here that Verma and her Saajhi Duniya team convey their message of progressive values and gender equality, helping residents apply for Aadhaar cards, open bank accounts, and learn about state and central government schemes.

“Badi ma’am has taught us a lot about women’s rights,” said Shabnam, a former ASHA worker and a grassroots leader of sorts in the community. “Earlier, we weren’t even allowed to venture outside our homes by our family members, but now we all go shopping till Munshi pulia (3 km away) alone. We have also all opened our bank accounts.”

Shabnam pointed out that many Muslim women in Indira Nagar now move around freely without purdah. “(Verma) told us the ways purdah can be repressive. She never told us to take it off, but also told us to not let it be used as an oppressive tool,” she added.

This story of shifting gender dynamics in a small neighbourhood is a snapshot of Verma’s lifelong mission to spark progressive change through conversation and sensitisation.

With a Socratic touch, she raises questions tailored to her audiences and helps them find an answer to the conundrums of their societal framework. Rather than trying to rush radical transformations, she focuses on bringing gradual changes.

“When I talk of gender equality, I just don’t restrict myself to women and try to open their eyes to victimisation. I also speak to men, and boys, and ask them how patriarchy is benefiting them— I help them see how it is toxic for them as well,” Verma said.

But with polarisation so deeply entrenched in society, spaces for dialogue and nuance are shrinking. Verma rejects RSS’ brand of politics, even though she talks about the many positives of Hindu philosophy. “Our culture has been about criticising everything, like breaking a hair into several parts while analysing a topic at hand. Sadly, that aspect of our culture is eroding. Today, nobody likes criticism,” she said.

That was the lowest point in my life, the time I looked evil in the eye

But the octogenarian has not lost her passion for change. Lucknow residents continue to visit her office seeking advice and solace. There’ve been offers to make films on her life too, but Verma has declined these.

Age has not dimmed her quietly authoritative manner. Her face bears the seasoned sternness of a veteran educator, which may seem intimidating, but though she is firm, even commanding, she never comes across as rude.

Verma has devoted her life to her intellectual and idealistic pursuits, choosing to never marry. “Some women in public service have successfully juggled household work with their work outside,” she said. “I didn’t think I could, or wanted to, do it.”

Also Read: ‘Hindustan is finally for Hindus.’ Ayodhya Express reaches Ram temple

‘Progressive’ beginnings

One of six siblings, Verma’s childhood in the small UP town of Mainpuri was shaped by forward-thinking parents. Her father was a doctor, and her mother, though she lacked a formal education, encouraged her daughters to expand their horizons and study.

“When we were young there was abject poverty and illiteracy around us. But it was also an inspiring time when the youth were charged up to make the nation successful. Everyone followed the teachings of freedom fighters and wanted to live up to their principles,” she said.

Growing up, Verma says she was fortunate to have a well-stocked library at home, brimming with socially conscious Hindi literature by the likes of Premchand.

“I had access to all these books, and we also read magazines like Dharmyug and Illustrated Weekly, which were largely progressive. That’s where I got fodder for what would become my progressive thinking going forward,” she said.

Like any ideology, feminism has many branches, and one of them actually believes women to be superior, goddess-like beings. We don’t subscribe to that ideology

However, Verma isn’t one to romanticise the past. Women in her household faced restrictions, and she had to find a way within those confines to carve out a space of freedom, she said.

While Verma’s parents wanted their daughters to graduate, their choice of Lucknow wasn’t solely based on academic merit—an elder brother, studying medicine there, served as a convenient local guardian to keep an eye on them. The hostel also had strict rules for women, ensuring they had no chance to stray from their regimented schedule.

“Me and my sister were the first women to be sent out of the town to pursue further studies. All kinds of things were said about us… But once they saw that we didn’t get ‘spoiled’ by staying in a hostel and studying, their attitude changed. And other women were also then sent out to study,” she said.

In the 1990s, Verma fell into the crosshairs of colleagues whom she’d accused of promoting the ideology of the RSS on campus.

Academic ascent and a nadir

In Lucknow, Verma decided to pursue a master’s degree in philosophy because she had scored the highest marks in that subject and believed she could excel in it.

While some friction with colleagues had already arisen over her politics and street activism, things took a sharp turn for the worst in the 1990s. The university’s combined psychology and philosophy department split, and Verma was appointed head of the latter. This move, she said, was unacceptable to some other teachers who started a campaign against her. At the time, Verma was also reportedly in the crosshairs of colleagues whom she’d accused of promoting the ideology of the RSS on campus.

“That was the lowest point in my life, the time I looked evil in the eye,” she said.

Her detractors in the faculty alleged that Verma had tampered with an examination, and conspired to give multiple students a zero on their Logic examination. A criminal case against her was lodged and her reputation in academic circles suffered a blow.

“There were protests in college against me. Students who had respected me so far, turned against me. Letters were written assassinating my character,” she recalled.

In a 2018 HuffPost interview, Verma also alleged that certain faculty members colluded with RSS members to oust her from her position so that someone affiliated with the organisation could lead the department.

ThePrint contacted several RSS office-bearers in Lucknow over the phone and message, but all refused to comment on Verma.

Facing not only public scorn but waning support from her family, who urged her to leave the university for a fresh start, Verma refused to back down. “I even had an offer from Hyderabad University but I didn’t take it,” she said. “I had to clear my name.”

Eventually, an investigation cleared her of any wrongdoing and, vindicated, she continued teaching at the university until her retirement.

Ankita Mishra, a former student and now a volunteer at Verma’s NGO Saajhi Duniya, remembers her professor as someone who opened her eyes to the many microaggressions that women face.

“She was the head of the women’s studies department when I joined in the year 2000 to pursue my MA,” Mishra said. “I thought now we can step outside the house, pursue education, work… where’s the discrimination here? But she helped me understand nuances. I understood the violence women go through on a daily basis, the kind of inequality that we usually don’t even have words to articulate.” Mishra has been volunteering with Sajhi Duniya for about 16 years.

Although Verma is still the driving force behind Saajhi Duniya, she is poised to pass on the baton.

Changing missions, constant core values

From distributing pamphlets on the streets, Verma’s grassroots work slowly evolved into organising large-scale community discussions to generate awareness about political and gender rights, leading to the founding of Saajhi Duniya in 2004. Although the NGO initially aimed to focus on fostering communal harmony, this now forms just one aspect of their work, taking a backseat to gender justice.

Saajhi Duniya currently helps victims of gender and sexual violence through counselling and legal aid. So far, the NGO has helped more than 5,000 victims find justice in big and small ways, according to Verma. However, the organisation distances itself from the label “feminist”.

“We’re not totally opposed to it, but we avoid using the word,” she said. “Like any ideology, feminism has many branches, and one of them actually believes women to be superior, goddess-like beings. We don’t subscribe to that ideology.”

India is not a kingship, it’s not a plutocracy. We’re for democracy and democratic principles

Rather than proselytising, Saajhi Duniya strives to bring change within communities by way of street plays and public discussions, often revisiting repeatedly neighbourhoods to consolidate changes. The organisation has also undertaken hundreds of sensitisation initiatives, including refresher courses on gender for several government departments and seminars for judges. “We go on invitation, but sometimes offer seminars even when we aren’t invited,” Verma said.

Bringing gender-inclusivity into education is another important dimension of Saajhi Duniya’s work. To make school curricula in Uttar Pradesh more gender-inclusive, they’ve not just written their own literature but also identified instances of gender bias in existing textbooks and submitted their critiques to the government.

These books were poised for inclusion in the academic curriculum during Akhilesh Yadav’s tenure as Uttar Pradesh CM, Verma said. However, the change in government in 2017 halted progress on this front.

Verma said that biases identified in textbooks ranged from stereotypical portrayals of women as engaged solely in household tasks to the problematic depiction of historical figures like Rani Laxmi Bai through the lens of beauty and domestic prowess. Additionally, certain chapters reinforced harmful stereotypes by presenting women as jealous and intellectually inferior.

To counter such portrayals, the NGO has written rhymes and poems to introduce feminist ideas to children in simple, catchy language. These are disseminated through workshops and outreach initiatives.

For instance, a poem called ‘Mera Ghar’ (My Home) in a book of poems called Saajhi Baatein (Shared Conversations) advocates for the equal division of household chores.

“Saaf safai, khana pakana, kabhi kare Nani, kabhi kare Nana (House chores are sometimes done by grandma, sometimes by grandpa),” it says. “Seena pirona, button taankna kabhi kare bhai, kabhi kare behna, tin tin dhinna, tin tin dhinnaaz chalo chalo sab mere angana (Sometimes my brother sews on buttons, other times my sister, come, come to my house).”

Although Verma is still the driving force behind Saajhi Duniya, a recent battle with a severe lung infection and the losses of friends and siblings have taken a toll and she is poised to pass on the baton.

“After much deliberation, I convinced my colleagues to appoint a new secretary,” she revealed with a smile. “Delegating to my young colleagues is crucial as my health doesn’t allow me to be as active as before.”

Distributing pamphlets is something that Verma has done less and less over the years, but raising public awareness about political rights remains core to her values.

“India is not a kingship, it’s not a plutocracy,” she said. “We’re for democracy and democratic principles. So, it becomes very important to go to the public on the ground and generate awareness about their rights, about the existence of inequality in society, and why that inequality exists.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)