In 2010, Mahasweta Devi’s 20-page story titled Draupadi published in 1978 was translated into English. In her re-telling of the story of the Pandavas’ wife, Draupadi — or Dopdi — is a tribal woman, a rebel fighting oppression and social norms. Devi engages with the complicated politics of Bengali identity and Indian nationhood by setting her story against the Naxalite movement in the 1960s, the Bangladesh Liberation War of West Bengal, and the ancient Hindu epic of the Mahabharata.

Eleven years later, the short story was dropped from Delhi University’s English Honours course in August 2021. Even today, Mahashweta Devi, who stood for the rights of the oppressed and wrote stories of the subaltern, has the power to rattle authorities.

She was a notable voice for the divided portion of society at a time when women had to advocate for their own rights through writing. Her best-known pieces include Rudali (1993), Hajar Churashir Maa (1974), and Draupadi. Mahasweta Devi’s entire body of work highlights the injustices and traumas suffered by indigenous population at the hands of those in positions of authority.

Also read: Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya is Fox regular, anti-lockdown. Twitter is his new foe

A literary force

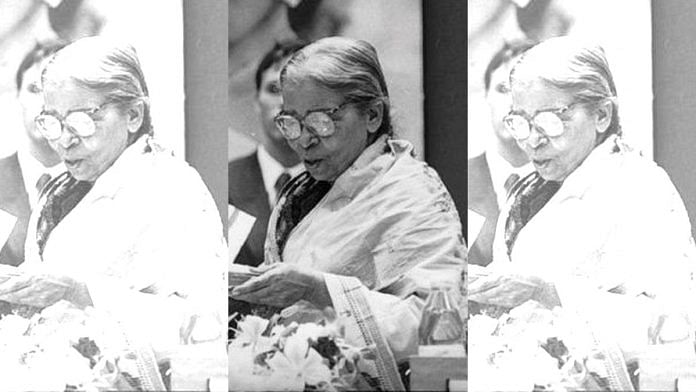

Born on 14 January 1926, in Bangladesh’s Dhaka in British India, Devi was the daughter of poet and novelist Manish Ghatak and the niece of renowned filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak. Her mother was a well-known social worker and writer as well.

She married Bijon Bhattacharya, one of the original members of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), in 1947, but they decided to separate in 1962. Her decision to divorce her husband was seen as a bold move by many at the time.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, she had established herself as a literary force to be reckoned with. She wrote on caste oppression, land grabs, suppression of people’s rights, and industrial closures. She fought for the rights of women, tribal people, Dalits, landless labourers, and migrants.

“I want to reach as many people as possible,” she said. “I write for the masses.”

It’s interesting to note that the everyday realities of rural life that inspired her to begin writing in the 1960s, when she was a college professor on the outskirts of Calcutta (now Kolkata), were largely the same realities that inspired the youth of the city to participate in the armed agrarian revolt at Naxalbari. The Naxalite movement is, in fact, the backdrop of her most well-known book, Hajar Churashir Maa, which was adapted for the screen by Govind Nihalani in 1998.

Her early experiences of selling soap, writing letters in English for illiterate people, and working in a post office—where she was fired for her communist beliefs—probably had an impact on how she saw the world.

Through newspaper articles, petitions, legal actions, letters to the authorities, activism, the grassroots journal she produced called Bortika, in which the disadvantaged reveal their own truths, and lastly, through her fiction. She had also led the Kheriya Sabar Kalyan Samiti, which worked for the financial upliftment of the downtrodden Sabar tribal people of Bengal. She also advocated for tribes like the Santals, Lodhas, Mundas, and others using her pen.

Also read: Ramashankar Yadav ‘Vidrohi’: The bard of JNU who challenged authority with poetry

Had global concerns

Her well-known book Aranyer Adhikar (Right to the Forest) (1977) is based on the life of Birsa Munda, a tribal freedom fighter, spiritual authority, and folk hero. Later, she firmly opposed the government’s seizure of tribal lands and spearheaded the West Bengal movement opposing the government’s industrial programme.

The Denotified and Nomadic Tribes’ Rights Action Group (DNT-RAG), a large organisation that currently keeps watch against similar crimes, was founded as a result of Mahasweta’s lecture on the situation of India’s denotified tribes in Vadodara in 1998.

She is credited with helping renowned author Manoranjan Bypari by encouraging the publication of his early writings in her journal.

“I have always thought that genuine history is formed by common people,” she once remarked when asked about her inspiration. Her biopic, Mahananda, directed by Arindam Sil, is based on her life and was released in 2022. In an interview, the director had remarked, “Like the River Mahananda, her principles should flow from generation to generation.”

Despite the fact that her stories had a regional flavour, her concerns were global. Over the course of her life, Devi received numerous honours for her contributions to literature, including the Sahitya Akademi Award, the Jnanpith Award, the Ramon Magsaysay Award, and India’s civilian awards, the Padma Shri and the Padma Vibhushan.

She passed away at the age of 91 on 28 July 2016 in Kolkata after suffering a heart attack.

(Edited by Tarannum Khan)