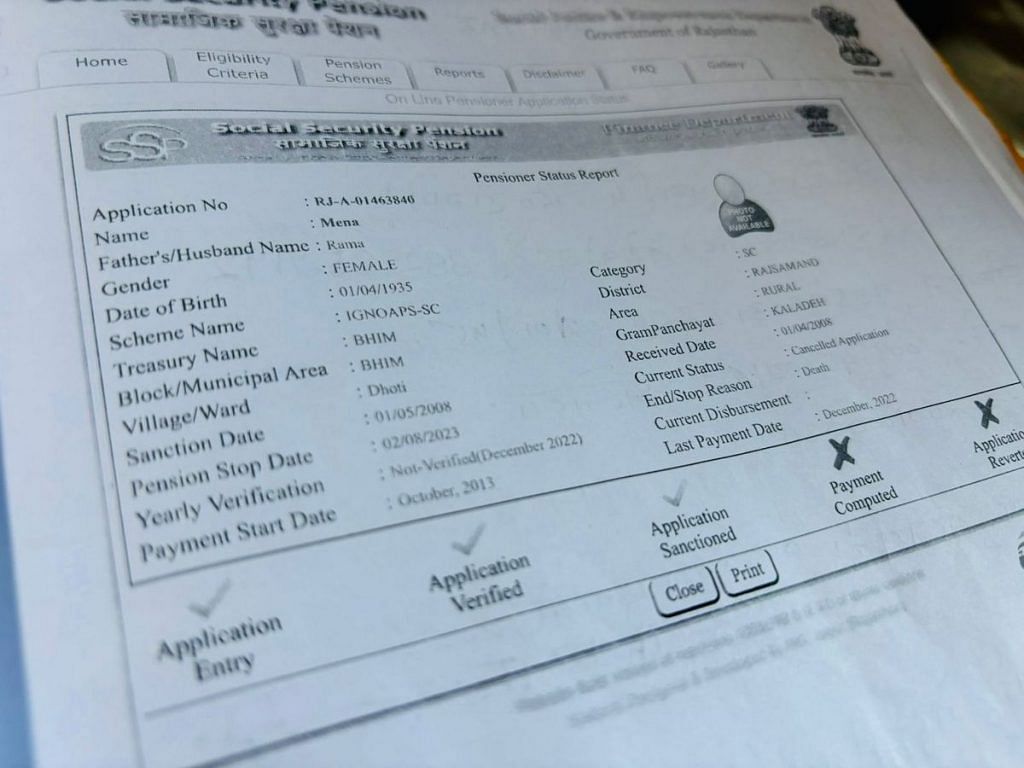

Ajmer/Beawar: In another world, 103-year-old Mena Rama would be dead. The Rajasthan government thought so too. When Rama’s nephew enquired why her pension and ration had stopped over the past two years, he was told she was no longer alive.

At least, that’s what the government’s KYC data showed in Jaipur.

Yet, frail as she is, Mena Rama is very much alive, lying on a charpai, her rheumy eyes shielded from the sun by a yellow dupatta. She hasn’t received her monthly pension of Rs 500 or her ration of 35 kg of food grains in nearly two years — both stopped coming in December 2022, when Rajasthan introduced mandatory eKYC for pensions. Five months ago, her two nephews carried her emaciated body from her tiny shack to theirs in their village in Rajsamand district’s Bhim tehsil, ashamed that neighbours had begun feeding her out of pity.

Mena Rama’s story punches an embarrassing KYC-shaped hole in Digital India. And she’s just one among lakhs in Rajasthan facing similar problems.

In a tiny house tucked away in the Aravallis, 90-year-old Lakshmi Devi in Ajmer’s Tatgarh village stopped receiving her pension of Rs 1,500 because she was listed as “out of state”—even though she’s never left Rajasthan. She doesn’t have an Aadhaar card, and her biometric data can’t be recorded; she’s blind in both eyes and her hands are so gnarled and twisted that her fingerprints can’t be taken.

The promise of Digital India is an inclusive dream. But some people are dropping off the map. The reasons vary, but the result is the same—people are being ‘digitally excluded’ from essential benefits. And they are often the most vulnerable — the elderly, widows, people with disabilities, the poor—who are erased from the system. They die digital deaths while waiting for pensions, rations, and NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) payments, blocked because their KYC isn’t done or their biometric data isn’t recorded in the Aadhaar database.

The years-old paranoid battle against Aadhaar was lost. This time, the anger isn’t with Aadhaar but with its implementation. The government has responded by addressing individual cases, but the problem goes far beyond isolated errors.

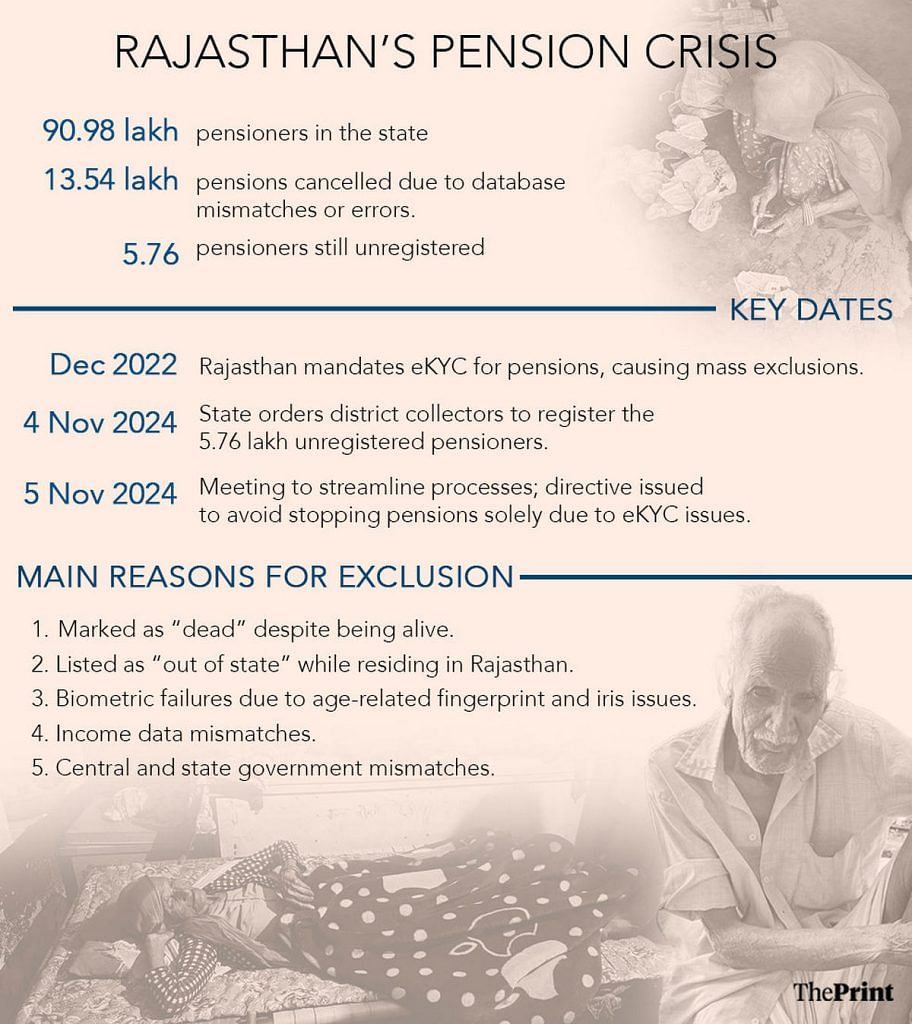

In Rajasthan alone, over 13.54 lakh of the state’s 90.98 lakh pensioners have had their pensions abruptly cancelled. Many are marked as “dead” or “out of state” in official databases, despite being very much alive and residing in their home villages. And these are the people who rely on state benefits for basic survival.

Mena and Lakshmi don’t have the strength or resources to chase down government officials and plead for their pensions. To them, the face of the government is no longer the sarpanch or block development officer—it’s an out-of-reach computer screen.

It’s a gulf in the system that’s finally drawing more attention.

I tried so hard to get my pension back. I pressed so many things and it still didn’t work! I’m old, and I’m tired

-Amri Devi, 88, whose fingerprints wouldn’t register on the biometric system

“This sort of exclusion cannot go on,” said former Supreme Court judge Madan Lokur via video recording at a press conference last month on the mass digital exclusion of pensioners in the state, held by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) in Delhi. “It’s a Right to Life issue now.”

By linking state benefits to Aadhaar and an Aadhaar-Based Payment System (ABPS), Digital India has started to work against those it was meant to help, argue activists. The irony is that a landmark 2018 Supreme Court judgement explicitly states that Aadhaar is not mandatory for social welfare payments.

“I call this digital murder,” said Ranjit, who works with the MKSS.

This is where civil society groups like MKSS have stepped in. For months, they’ve been documenting Rajasthan’s pension crisis and holding camps to help excluded pensioners navigate an opaque digital maze. Now, the problem has grown too big for the Rajasthan government to ignore. After MKSS’s press conference, officials have jumped into action to plug the gaps the activists had highlighted.

Rapid orders have been issued from the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment in Jaipur to district magistrates across the state to look into the issue and make amends.

But for Ram Sewak Sharma, the first director-general of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), the problem boils down to lack of awareness rather than access, pointing out that there are “800 million” smartphone users in India.

“Doing things digitally is an improvement over doing things physically,” Sharma said. “Every household has at least one smartphone. You don’t have to own one to authenticate your identity. It’s a question of raising awareness on how to do it — that’s something that the government will have to put more effort into.”

The entire process of applying for pensions or updating details on the pension portal is a Kafkaesque nightmare — a 15-step process that can go awry anytime.

Also Read: Young Indians are making Khatu Shyam cool. Govt is playing catch-up with new temple corridor

Jumping through hoops

Tipu Devi, who used to receive a monthly pension of Rs 750 as a widow, rifles through her bag, pulling out scraps of paper at the door of her hut in Bhim tehsil.

All her most prized possessions are in this one bag: her Aadhaar card, her pension slips, and her husband’s death certificate — each category of government ID safely kept in a separate plastic bag.

She’s searching for the right piece of paper to show MKSS co-founder Shankar Singh, so that he can check her pension status. Finally, she tips its contents onto the ground and looks up helplessly.

Singh then spots a pension payment slip and reads out the Pension Payment Order (PPO) number to his colleague Ranjit, who quickly types it into the payment portal. Tipu Devi’s profile pops up, showing her name, age, address, and the last date she received her pension. She drew her pension every month from August 2013 until January 2022. The reason listed for the stoppage: “member record deleted on Janaadhar”—a misspelling of Jan Aadhaar, Rajasthan’s own unique ID system linking residents to government services and benefits.

But the portal doesn’t say why Tipu Devi’s record was deleted. Ranjit downloads her details and saves them as a PDF—another case added to a growing list of pensioners left without benefits. But because Tipu Devi has an Aadhaar number and appears to have been registered on Jan Aadhaar at some point, re-registering her might not be too hard.

Others are not so lucky.

Ninety-two-year-old Dhapu Devi was first written off as dead. After her grandson, Santosh Kumar, persistently followed up with local authorities, it was updated to “member record deleted on Janaadhar”—just like Tipu Devi. Now, they’re stuck.

The onus is on the citizen to prove their identity, when it really should be with the state. How can you expect such people, the most marginalised of the poor, to spend their lives running after the government?

-Shankar Singh, MKSS co-founder

Dhapu Devi has neither an Aadhaar card nor a Jan Aadhaar card. She does have her Voter ID, ration card, and NREGA card, but these documents don’t help her get back into the system. Her family has carted her to the local e-mitra kendra—Rajasthan’s so-called one-stop digital service centre—at least four times to try and register her biometrics. But each time, her fingerprints wouldn’t scan properly—her hands are too worn. The local sarpanch even wrote a letter in 2023 certifying she’s alive, yet she still hasn’t received her Rs 1,000 pension.

“They said she’s dead, but here she is sitting alive next to me,” said Bhagwati Kumar, Santosh’s mother, her voice rising in frustration while she stroked her mother-in-law’s bony arm. “I even asked the sarpanch to write a letter. I asked the collector sahab why she was declared dead. Why should we have to go to a different district just so that she can get her pension that the government only stopped?”

For many pensioners in the state, December 2022 was when their digital identities—and their pensions—started to vanish. That’s when Rajasthan made eKYC mandatory for pensions. As a result, lakhs dropped off the registry.

The reasons for this exclusion vary. Some pensioners were mistakenly marked as dead, others were deemed “out of state”, and some suffered because of data mismatches between state and central government records. Centralised verification issues and eKYC challenges—often only resolvable by the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment in the state capital—added another layer of red tape.

Additional complications arise when family income isn’t updated, when a widow remarries, or when there’s an age mismatch across different ID cards—a common occurrence in rural India, where many elderly people don’t know their exact birthdate.

“I tried so hard to get my pension back. I pressed so many things and it still didn’t work!” said 88-year-old bedridden Amri Devi, who lives in Aasan in Jawaja block, remembering how her fingerprints wouldn’t register. “I’m old, and I’m tired.”

The entire verification process can drag on for months, requiring multiple follow-ups. For the elderly, this often means relying on younger relatives for each office visit—a challenge for families surviving on daily wages.

‘A game of snakes and ladders’

The entire process of applying for pensions or updating details on the pension portal is a Kafkaesque nightmare — a 15-step process that can go awry anytime.

The system is a maze that can trap any pensioner not savvy in paperwork. First, they need an Aadhaar card—but in Rajasthan, that’s not enough. It must also be linked to the Jan Aadhaar, which includes the socioeconomic data of the entire household. Next comes eKYC verification and logging updated details on the pension portal. If everything lines up, payments should start arriving in the first week of every month.

But often, it doesn’t go smoothly. Then it’s time to go from pillar to post. If a pensioner is listed as “dead,” “out of state,” or has any data mismatch, they have to physically take their documents to the local panchayat, which issues a letter to the state social justice department. The letter is sent to the block office, which then requires biometric verification, often requiring yet another trip. If everything checks out—no biometric issues, every document in place, a phone number correctly linked to Aadhaar—an OTP is generated, which must be entered on the portal. Only then do the payments start.

Even this is still a best-case scenario. Very often, local officials demand documents the pensioner doesn’t have, forcing another round of applications. Or they’ll flag mismatches that should have been fixed three steps earlier.

“This entire process is like a game of snakes and ladders,” said Singh. “You get to go one step forward and then suddenly you’re back to where you started.”

The entire verification process can drag on for months, requiring multiple follow-ups. For the elderly, this often means relying on younger relatives for each office visit—a challenge for families surviving on daily wages.

“What does all this technology mean if it can’t help the most needy?” asked MKSS’s Shankar Singh after a particularly painful visit to the home of Pyaari Devi, another resident of Bhim tehsil. Her two adult sons, both severely disabled, haven’t received disability payments in months. Barely clothed, they watch her every move as she rifles through identification papers she can’t read.

“The onus is on the citizen to prove their identity, when it really should be with the state,” said Singh. “How can you expect such people, the most marginalised of the poor, to spend their lives running after the government?”

The situation also reflects a glaring disconnect between legal rulings, government policy, and ground realities. In its 2018 judgement on Aadhaar, the Supreme Court was clear: the document is not mandatory for the disbursement of welfare services. A 2024 Supreme Court order reiterated this ruling, specifying that Aadhaar’s main purpose is simply to identify beneficiaries for transferring benefits, subsidies, services, and other purposes.

“This was the primary reason,” noted the 2024 order—”To ensure correct identification of targeted beneficiaries for delivery of various subsidies, benefits, services, grants, wages and other social benefits schemes which are funded from the Consolidated Fund of India.”

The state’s response

A week after the MKSS held its press conference in Lutyens Delhi, the Rajasthan government finally swung into action.

On 4 November, Kuldeep Ranka, additional chief secretary of the Social Justice Department, sent a letter, accessed by ThePrint, to district collectors across the state. He pointed out that of Rajasthan’s 90.98 lakh pensioners, 5.76 lakh were still unregistered and needed to be added immediately. This number is in addition to the 13.5 lakh, per government figures, who’ve had their pensions cancelled for various reasons.

The directive from the Social Justice Department further says that gram panchayats must be involved in verifying whether pensioners are still alive; it also mandates their approval if someone is declared ‘dead’ or ‘out of state’.

A second letter from the department instructed that action be taken against “those responsible”—though it is not specified who —and that stopped pensions should be restarted immediately.

On 5 November, a follow-up meeting was held to streamline the process. The department clarified that pensions should not be cut off due to eKYC issues, and that the Jan Aadhaar database should be used as for pensioners’ data.

“We’re taking data from Jan Aadhaar now—but if someone is not on it, they shouldn’t be deprived of receiving their pensions,” said Bachnesh Agarwal, director of the Social Justice Department, who was involved in the discussion. “If there are technical difficulties, all district magistrates have been instructed to address the problem.”

In a sense, though, it’s just replacing one hurdle—Aadhaar—with another: Jan Aadhaar. Pooran Singh, deputy director of the pensions division of the Social Justice Department, explained that while Aadhaar is not mandatory, Jan Aadhaar has become the norm in Rajasthan.

“It’s true that in many cases people are listed as out of state or dead, but that is an anomaly,” he insisted. “This would have happened because their biometric authentication must not have been done, or our field agents were able to verify them.”

He added that if biometric verification is not possible, citizens can visit the sanctioned authority—the Block Development Officer (BDO) in rural areas or Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) in urban areas—and have their OTP generated from the number linked to either their Aadhaar or Jan Aadhaar.

It’s true that in many cases people are listed as out of state or dead, but that is an anomaly. This would have happened because their biometric authentication must not have been done, or our field agents were able to verify them.

-Pooran Singh, deputy director of the pensions division of the Social Justice Department

To address the issue of those without Aadhaar, the department plans to allow OTPs to be generated through Jan Aadhaar alone. However, this raises similar questions.

“The person can use their Jan Aadhaar and 16 other documents to confirm their identity,” he said. “Since Aadhaar is not mandatory.”

But Jan Aadhaar has its own challenges, including central bottlenecks.

In March 2024, the central government said that it will only release funds for disability pensions when the disability certificate of the pensioner is uploaded on its Unique Disability ID (UDID) portal.

To meet this requirement, Rajasthan stopped accepting new disability applications on the Jan Aadhaar portal from 7 March and attempted to port its database onto the UDID portal via API—post an MoU with the central government. However, the central government has yet to share its data with Rajasthan. The state, therefore, cannot compare records and ensure there are no duplicate entries of beneficiaries.

As a result, not one disabled person in Rajasthan received their disability pension for seven months. No fresh applications were accepted, and those who were trying to reinstate their pensions were also left in limbo. It’s left lakhs of people — like Pyaari Devi’s family — in the lurch.

To address this lapse, the pensions department is now allowing people with disabilities to verify their identities through their sanctioned authority’s phone. This means that a BDO or SDM can receive the OTP on their own phone and complete the verification process on behalf of the beneficiary.

The Social Justice Department is currently considering extending this workaround to elderly pensioners as well.

“This is in discussion now,” said Pooran Singh. “We’re working on it.”

Activists argue that withholding pensions, rations, and NREGA payments due to incomplete KYC or biometric mismatches is a violation of Article 21, the Right to Life.

Not just a Rajasthan problem

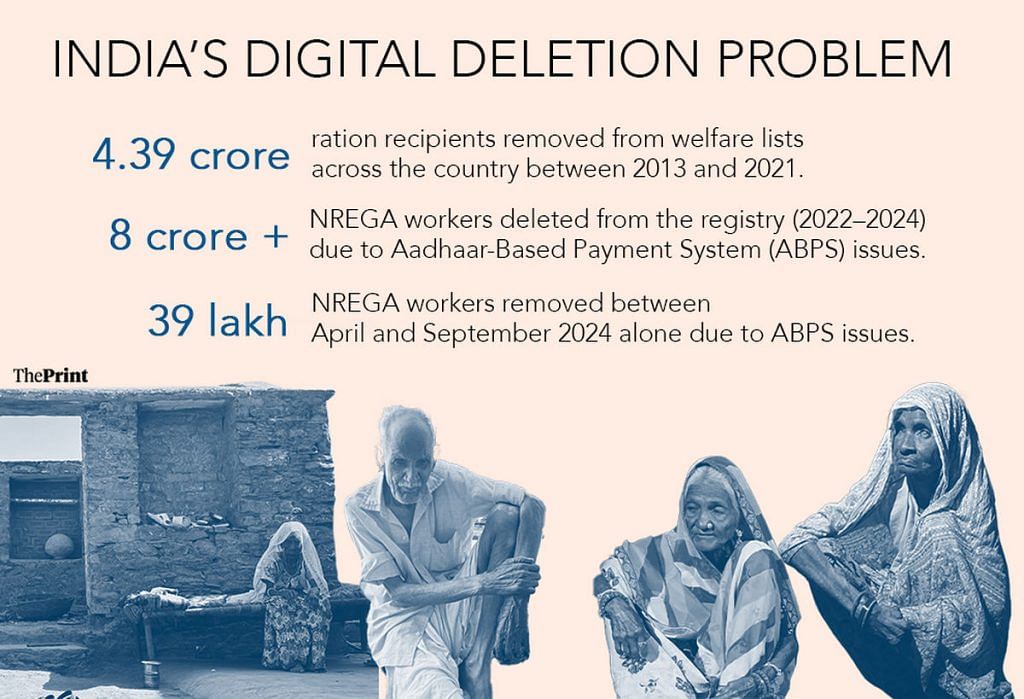

The digital exclusion problem goes far beyond Rajasthan. Throughout the country, many citizens are missing out on their pensions, rations, and NREGA payments—the three main pillars of support for the poor.

Every November, pensioners across India are required to prove they’re alive. In the past, this meant a physical visit to the bank. But in 2014, the government introduced Jeevan Pramaan—a digital ‘proof of life’ certificate that uses biometric authentication and doesn’t require an OTP.

“Rather than going to the bank, now you can do it digitally. It’s an improvement if pensioners can do their verification at home through face authentication,” said former UIDAI director-general Ram Sewak Sharma. “The question is, how many people take advantage of this improvement? Obviously those who don’t use digital devices are excluded.”

These lacunae are not limited to pensions.

NREGA payments are now connected to the ABPS, which links a worker’s Aadhaar to their job card and bank account. This too requires eKYC to map them on the national payments platform. The shift has led to widespread exclusion—over 39 lakh registered workers were deleted from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) between April and September 2024 alone. From 2022 to 2024, more than 8 crore workers were removed from the registry, largely due to ABPS-related issues.

The state has been able to create (digital) infrastructure and enrol most of the country. But the purpose of a state-led policy is not to count only successes. A government is for everybody.

-Tanveer Hasan, executive director of the Center for Internet and Society

The same problem exists with rations. From 2013 to 2021, nearly 4.39 crore recipients were deleted from the Public Distribution System across the country, according to an RTI response from the government.

There are 314 other such centrally sponsored schemes, intended to transfer benefits directly into citizens’ bank accounts. But for those who are not using ABPS, these schemes may well not exist.

Instead of delivering the intended transparency, the implementation of a universal digital infrastructure has created new layers of opacity.

Activists argue that withholding pensions, rations, and NREGA payments due to incomplete KYC or biometric mismatches is a violation of Article 21, the Right to Life.

“We’ve been doing this for forty years. We know that when you’re dealing with mass systems, it’s inevitable for people to be left out,” said Nikhil Dey, co-founder of the MKSS. “But there’s this obsession of technocrats that technology will solve everything—and if there’s a problem, it’ll be fixed by tech.”

Dey contends that going low-tech is now the need of the hour.

“The only way to fix this is to find decentralised, offline, public means of doing it,” he added.

What Dey and other activists propose is a governance model in which local elected bodies, like panchayats, disburse social welfare benefits without needing centralised database authentication.

Policy should build resilience into digital systems, say tech policy analysts. If something fails, there should be a backup or a Plan B, even if it means using manual alternatives for tasks like verifying if a pensioner is still alive or not.

“Yes, the state has been able to create (digital) infrastructure and enrol most of the country. But the purpose of a state-led policy is not to count only successes,” said Tanveer Hasan, executive director of the Center for Internet and Society. “A government is for everybody.”

Also Read: Jaipur’s grand new Coaching Hub is a ghost town. Desired by students, dodged by institutes

The price of a dignified life

The cost of losing a pension in a village is high. It can make all the difference between a life of dignity and one without it.

Back in Bhim tehsil, Bhagwati hobbles home, swinging a plastic bag of snacks, her face lit up with joy. She’s not sure of her age and has no living relatives, but she’s in a great mood because she’s just bought herself some namkeen to accompany a drink that she’s treating herself to.

Unlike many of her elderly peers, Bhagwati receives both her pension and her rations. She lives alone and independently, her cheerful, self-assured demeanour a stark contrast to the worry weighing down many others.

“I’ve lived a long life and I’m happy to be comfortable now,” she said, peppering her conversation with colourful swear words. “Everything is peaceful.”

Bhagwati’s dignity in old age—and her infectious happiness—is striking. She’s a reminder of what a steady pension and ration can do for a person. With no family to support, she can spend her pension on herself, giving her the freedom to live on her own terms. For lakhs of others, like 86-year-old Nainu Devi, pensions are not just personal income but important for the entire household. Also from Bhil, Nainu Devi is being cared for by begrudging relatives who say her pension helped ease their burdens too.

While Bhagwati’s financial independence may be unique, her contentment should be the norm, many say.

Yet, the system works in unpredictable ways. Bhim resident Jeetu said his 86-year-old widowed grandmother’s pension stopped recently after 25 years. When they went to check why, the reason listed was that she was ‘married’, and therefore not entitled to a widow’s pension.

“Who gets married at 86?” laughed Jeetu at the e-mitra kendra in Bhim, which the MKSS operates. Even on a weekend morning, four elderly people had come by to check on their pensions and other payments.

Rukma, the elected sarpanch of a nearby village, quoted her 100-year-old grandmother Amri Devi’s frustration when she stopped receiving her pension in December 2022

“If the government can come all this way to take my vote, why can’t they come here to make sure I get my pension?” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)