Jaipur: Mohammad Abid has a dream, and it has already drained ten years from his life. And he is not even close to achieving it. At 33, he is still waiting to be a government school teacher. As he waits for resolution in Rajasthan’s mega paper leaks racket, Abid juggles jobs as a mason, house painter, and newspaper vendor.

Many like him have lost their precious youth waiting for recruitment in government jobs, a process bedevilled with leaks, organised cheating, re-examinations, cancellations—be it for teaching positions or jobs as health officers, police constables, or forest guards.

Now, Abid and around 500 others are camping out at Shaheed Smarak, a protest site opposite the Police Commissioner’s office in Jaipur. They are demanding recruitment once and for all. Their lives stuck in limbo, there’s not much else they can do for now.

“I am attracted to the teaching profession because of the respect a teacher enjoys in society,” Abid said softly, his palms rough like sandpaper from years of manual labour. “I was at the brink of selection. But my ordeal is just not ending.”

Most of the protesters at the site share the scars of the 2021 Rajasthan Eligibility Exam for Teachers (REET) paper leak. Over 16 lakh candidates vied for around 31,000 posts that year. The results were declared in January 2022, but amid allegations of cheating, misconduct, and the ensuing political controversy, the state government cancelled the entire exam. When it was re-conducted, Abid passed the test once again. But Rajasthan government officials are allegedly stalling recruitment over a technicality and Abid’s dream hit a roadblock again.

This happens when people of integrity are not appointed—the responsibility of which lies squarely on those in power

Rajendra Bhanawat, retired IAS officer & former RPSC secretary

Rajasthan is one among several states wrestling with the paper leak menace. Almost an epidemic, leak operations are well-oiled, organised machineries of corruption involving criminals, student mafias, coaching centres, principals and officials. From Jammu & Kashmir to Karnataka, from Gujarat to Arunachal Pradesh, at least 41 officially acknowledged instances of paper leaks have taken place across India in the last five years.

Rajasthan alone has witnessed over 25 cases of exam leaks in the last decade, cutting across both Congress and BJP governments. However, the issue escalated significantly in the last five years under former chief minister Ashok Gehlot. All the recruitment agencies in the state—including the Rajasthan Public Service Commission (RPSC), Rajasthan Board of Secondary Education (RBSE), and Rajasthan Staff Selection Board (RSSB)—have been hit by this fiasco.

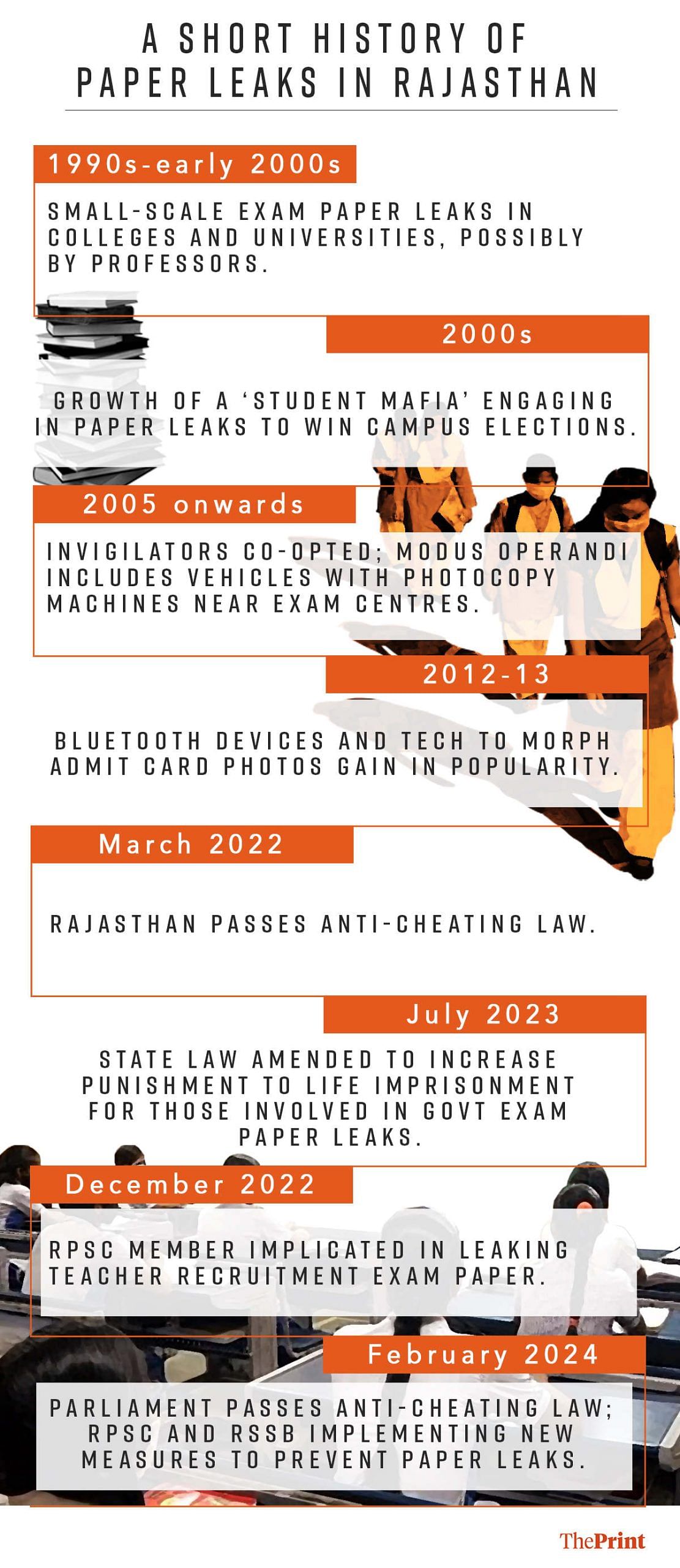

The problem has snowballed into a major political issue, dominating state election campaigns and assembly debates. In March 2022, Rajasthan even passed an anti-cheating law, later tightening its provisions to include life imprisonment as a punishment, well ahead of the Indian Parliament passing a similar legislation in February 2024.

In the past decade, hundreds have been arrested in just Rajasthan, and many more across India. For the youth, the consequences of paper leaks are devastating. It is life interrupted, strained family ties, and fractured social lives. And the inability to recruit severely dents state capacity to deliver services.

“We should see how much of the nation’s time and money is wasted when papers get leaked. If 5-6 lakh youth are preparing for an exam and the paper gets delayed, the amount runs up to crores,” said retired IAS officer Rajendra Bhanawat, who briefly worked as RPSC secretary in the early 2000s.

The hunger for a government job burns bright, pushing aspirates to persevere until they reach 40, when the official age limit kicks in.

Also Read: ‘Israel is a strong country, Indians will be safe there’ — Haryana workers storm job drive

Pushed to the wall

It’s been over a fortnight since Mohammad Abid left his home in Jodhpur district’s Bilara with only an extra pair of clothes, a blanket, and Rs 800 in his wallet. The 33-year-old has been staying in Jaipur to demand his appointment as a government school teacher. He has cleared two qualifying exams, but now faces a new hurdle due to uncertainties from the state government about his academic eligibility.

In the city, he sleeps at a government shelter and lives off free meals provided by gurudwaras and Good Samaritans. But he is holding out hope that protesting will get him the job that will catapult him out of poverty. Depending on the class he gets assigned to teach, he can bring home Rs 37,800 (classes 6-8) or Rs 44,300 (classes 9-10). Besides REET, he has also cleared the Senior Teacher (Grade II) exam. He points out he passed REET in 2021 despite high cut-off marks—a telltale sign in cases of leaked test papers, according to several candidates.

However, an ‘additional degree’ is an albatross around Abid’s neck. He cleared the exams to teach Urdu, but he didn’t study it during his undergraduate programme, instead completing a separate one-year degree for it. The government now refuses to accept such candidates. It’s another problem in Rajasthan’s rabbit hole of recruitment logjams.

Abid contrasts his plight with that of previous REET candidates who managed to get appointed despite sharing the same “ambiguous” qualification, but he is not alone. Protesters claim that around 700 others across the state are now stuck because of this new rule.

One such candidate is Pooja Sen, a single mother. Much like Abid, she patiently waited for the 2021 paper leak issue to be resolved and retook the exam. But this technicality has created a fresh hurdle, pushing her to breaking point. Neither Sen nor Abid participated in earlier protests over the leaks, but now they have no other recourse but to agitate.

“I suffer from arthritis and live with my parents and elder brothers. During Covid, I became bedridden and lost my job at a private school,” Sen said. “A government job will put an end to all the problems and earn me respect.”

With their aspirations thwarted yet again, these candidates are now forced to juggle protests and rounds of ministers’ and bureaucrats’ offices to seek a solution.

Back when the leaks happened, frequent protests took place in Rajasthan, often dealt with through water cannons and lathi charges. It was a similar tale in Bihar too, with pictures of leaked papers going viral, followed by protests marred by vandalism and violence.

We have stopped attending weddings or social gatherings. Villagers accuse us of lying about our appointments. In Rajasthan, social life depends on government jobs

-Ashok Patel, govt job aspirant

But even if anger over paper leaks temporarily disrupts social stability, life eventually resumes its course for exam aspirants. The hunger for a government job burns bright, pushing them to persevere until they reach 40, when the official age limit kicks in.

Despite widespread criticism and scrutiny from all corners of society, the cycle continues unabated.

“This happens when people of integrity are not appointed—the responsibility of which lies squarely on those in power,” retired civil servant Bhanawat said. “Undeserving” appointments, according to him, are sometimes made due to indifference. “Other times,” he added, “it’s collusion which could be for corruption or comfort. Those who are supposed to be the protection wall get in connivance with people who leak papers.”

‘Fatal obsession’ with sarkari naukri

At Shaheed Smarak, a protester shouted into a loudspeaker about a fellow candidate’s engagement being called off because he failed to get a government appointment. This opened a floodgate of anecdotes among the crowd about how they had suffered too.

Even three decades after economic reforms, a government job remains the most hallowed and respected profession in Rajasthan. Holding such a position not only provides immense leverage in negotiating marriage prospects but can drastically alter social status and mobility for the marginalised.

“We have stopped attending weddings or social gatherings. Villagers accuse us of lying about our appointments. In Rajasthan, social life depends on government jobs,” said Ashok Patel, 25, who has travelled from Piplod village to demand his appointment as a primary teacher. Several motley groups of aspirants fill the site, all with specific demands, but united by their desire for a government job.

It’s a dire situation for everyone at the protest ground. One disabled protester, Ramesh Soda, threatened to take extreme measures if his appointment wasn’t finalised.

For Abid, becoming a teacher would not only bring laurels within his community but also elevate his status in the village.

“It was my father’s dream to see his children were educated. When the REET results were declared, my father was so happy that his son could become a government school teacher,” said Abid, who finds solace in the poetry of Iqbal and Rahat Indori, and the writings of Vijaydan Detha. Abid’s father passed away before the exam was cancelled. He considers it “good timing”—at least his father died happy. Currently, his immediate concern is the fast-vanishing money in his wallet.

Meanwhile, fellow protester Bablu Regar, unemployed for months, is nursing a broken heart. Originally from Tonk, the 36-year-old said he had no interest in a government job, but his girlfriend and her family did. Thus began his quest to get a revered sarkari naukri, with stints as a private school teacher and security guard along the way.

He lives like a fakir now, his reflections on his situation vacillating between anger and philosophical resignation. “It’s difficult to manage money for those who are employed, not for the unemployed,” he joked. As for his girlfriend, she is now engaged to another man. “Sometimes, people fight more for the dream of others,” said Regar, whose passion for pursuing a government job has outlasted his love story.

“There’s a fatal obsession with government jobs,” said Bhanawat, comparing Rajasthan to the prevalent culture in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, and the northeastern part of India. Unlike neighbouring Gujarat, where youth are widely employed in the private sector, here nothing can shake the primacy of a sarkari post.

“There is money in the government sector even for Grade 3-4 jobs,” Bhanawat said. “Private sector employment is seen as exploitative and comes with a sense of job insecurity.”

This week, the arrest of four “kingpins” in a 2020 paper leaks case also came with a telling revelation about their alleged motive, other than minting money: securing government jobs for their relatives.

According to the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey, Rajasthan’s unemployment rate stood at 30.2 per cent for the 15-29 age group for July-September 2023, the second-highest nationally.

Tracing the beginning

Throughout the year, Shaheed Smarak is thronged by protesters rallying for various employment-related issues — paper leaks, job appointments, restoration of temporary job posts. The battered state of Rajasthan’s employment landscape is reflected in this site. In the middle of the open space is a towering white monument dedicated to fallen soldiers, where the angry young men and women of the state often congregate. They are testaments to the state’s unemployment rate—which, according to the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey stood at 30.2 per cent for the 15-29 age group for July-September 2023, the second-highest nationally.

While paper leaks have become more frequent in the state in recent years, the problem’s roots lie in Rajasthan’s college and university exams, dating back to the 1990s, according to a senior police officer with extensive experience investigating such cases.

“During the early 1990s up to the early 2000s, when college and university examinations took place, the papers would be leaked by the professors. Either the student leaders coerced them or private institutes lured them,” the police officer said, requesting anonymity. Student leaders, he added, would procure question papers to increase their chances of winning college and university elections.

Retired civil servant Bhanawat concurred, recalling the dominance of the “students mafia” during his tenure as Rajasthan University registrar in the early 2000s. He reasoned that the practice was probably rampant because state government vacancies were largely filled based on college exam results at the time.

Later, with the declining significance of graduation marks and the shift towards recruitment exams, the coaching industry came into existence. With the addition of new stakeholders, the business of paper leaks also expanded, with several players involved in the supply and execution chain.

Describing the evolution of the modus operandi over 30 years, the police officer said that the current system of papers leaking mostly from the exam centre is a relatively recent development.

Regarding paper leaks, there has been no such instance for the last 10 years. The recent incident that happened was very unfortunate. One of the members sold the paper in the market. This is a personal misconduct.

-Sanjay Shrotriya, RPSC chairman

In the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, he said, the RPSC papers were submitted manually. This allowed candidates to submit forms together to get sequential roll numbers. Often, candidates from rich families would collude with intelligent students from less privileged backgrounds. They’d submit the forms together, sit adjacent to each other, and exchange roll numbers during answer sheet submission.

After 2005, the police officer noted that a new layer was added to the cheating mechanism: invigilators were co-opted. Candidates, upon learning of their exam centres through their admit cards, would fix deals with invigilators by contacting the centre director.

“Another thing that started happening was a Maruti Van would be stationed near a centre which would have a photocopy machine. The paper would be opened 30-40 minutes before the exam and would be delivered to the vehicle,” the officer said. There would be people stationed in the van to solve the questions. The answers would then be photocopied and delivered through the invigilator or even water vendors.

Rajasthan isn’t the only state battling the cheating disease and it is not confined to government exams. In 2015, for instance, a photograph of parents scaling the walls of a three-storey building in Bihar went viral. They were throwing notes through the window to help children cheat in their high school exams, and all of it was caught on cameras in broad daylight. Paper leaks and cheating have even made it to Bollywood scripts. In the 2010 movie Golmaal 3, Arshad Warsi’s character boldly tries to sell exam papers on a college campus for Rs 2,000. Tusshar Kapoor and Kunal Khemu’s characters vouch for the legitimacy of the previous papers he had sold and students eagerly buy them.

Now, though, cheating techniques have become a little more refined. Around 2012-2013, technology began to play a bigger role, Rajasthan police officer said, with Bluetooth devices hidden in clothes, jewellery, and sandals. Technology was also used to morph pictures in admit cards, allowing dummy candidates to take the exams.

“Nowadays, the leaks happen through staff or members associated with the exam-conducting body,” he added. The officer, like Bhanawat, attributed the trend to political recruitment. “Only when big action is taken against the accused, will this problem stop,” he said.

For every solution the RPSC brings, there exists a “research and analysis wing” among those seeking new methods of cheating, according to its chairman Sanjay Shrotriya.

Family ‘favours’, dark nexuses, damage control

The RPSC and RSSB, which conduct the bulk of the Rajasthan government recruitment exams, have a fair bit of reputational damage to undo, with some “scandals” still fresh in people’s minds.

One tale of misdirected paternal devotion dates back to a decade ago, but still fuels gossip sessions. In 2013, then RPSC chairman Habib Khan Gauran allegedly copied the questions of the Rajasthan Judicial Services exam for his daughter, using his position as cover. Gauran was accused of visiting the printing press in Ahmedabad where the paper was being printed and jotting down the questions under the pretext of proofreading. His daughter scored the 10th position in the exam that year.

Another major controversy erupted in 2022, months after the state passed the anti-cheating law. RPSC member Babulal Katara, who was in charge of setting the exam paper to recruit second-grade teachers, allegedly leaked it for Rs 60 lakh. The paper-leak nexus in the case included a coaching centre owner, Suresh Dhaka. In the wake of the case, the government demolished the building housing the institute in Jaipur. Katara was arrested by the Enforcement Directorate and remains behind bars.

It’s been my endeavour to try and educate not only examinees but the invigilators, police personnel, exam centre staff and chaiwalas— anyone who is involved in the exam process (about the anti-cheating law)

-Major General Alok Raj, chairman, RSSB

The RPSC has distanced itself from the embarrassment, terming it not a paper leak but a personal “misdemeanour” by Katara.

“Regarding paper leaks, there has been no such instance for the last 10 years,” said RPSC chairman Sanjay Shrotriya. “The recent incident that happened was very unfortunate. One of the members sold the paper in the market. This is a personal misconduct.”

Despite the image damage, morale at the commission remains high. Shrotriya claimed that the RPSC immediately halted the exam process upon suspecting a leak. “The question paper wasn’t opened at the centres. We gave a new date for the exam and conducted it afresh,” he said.

Preferring not to dwell on the shocking incident, the RPSC chairman highlighted the many “fair selections” that have been achieved through the successful administration of exams.

Officials of both the RPSC and RSSB claimed that they are constantly implementing new measures to regain trust, pointing out that the last officially acknowledged paper leak occurred a year ago.

Shrotriya shared the commission’s “innovative” methods to prevent leaks. For instance, during the last Rajasthan Administrative Service preliminary examinations, they introduced the concept of the “fifth option”. In this system, candidates are not allowed to leave any answers blank. They must now select ‘E’ for questions they choose not to answer with one of the four standard options (A, B, C, and D).

“The RPSC is going to do it for every exam. The RSSB has also adopted this system,” he said.

Beyond system improvements, Shrotriya acknowledged the tougher issue of a “perception” problem. He attributed this to intense media coverage, which, according to him, had not always been portrayed the facts “correctly”.

Another RPSC official expressed a similar grouse, stressing that paper leaks were hardly unique to Rajasthan. “The media reporting about Rajasthan may be a little bit more. But if you compare, you will find Rajasthan isn’t ahead of other states as far as leakage is concerned,” he said, requesting anonymity.

The RPSC chairman attributed the recent problems in conducting exams to a surge in candidates. Where the commission previously dealt with around 2 lakh candidates, that number has now doubled to 4 lakh. Shrotriya said this was a fallout of the government’s “free” exams policy. This policy, according to him, attracted “unserious candidates” who filled up forms, leading to a strain on resources needed to conduct the exams effectively. “The bigger the exam, the riskier it gets to conduct an exam,” he said.

This spike in exam takers ties up with the “perception” issues raised by Shrotriya. Exam-conducting bodies have faced criticism not only for paper leaks but also for alleged incompetence in maintaining exam rosters and other administrative aspects.

Yet, most legal accusations levelled against the RPSC failed to hold water, he said. “In the last 1.5 years, the court has dismissed around 680 cases against us and termed them baseless,” Shrotriya added. He further mentioned the involvement of the “coaching mafia” in manipulating the system, claiming it benefits them when “the exam calendar runs late”.

For every solution the RPSC brings, the chairman sighed, there exists a “research and analysis wing” among those seeking new methods of cheating.

Also Read: Haryana govt shows Dubai dream to bouncers. But FIRs, tattoos, violence scars come in the way

Army man in control at RSSB

Between the RPSC and RSSB, the latter has suffered more damage to its reputation. A string of leaks across various exams, including those for the recruitment of community health officers, forest guards, and junior engineers, forced Ashok Gehlot’s government to appoint a new head of the board.

To squash allegations of political appointments, Gehlot brought in retired Major General Alok Raj to helm the RSSB. Six months in, the army veteran boasts a successful record of five smoothly conducted exams. He expresses confidence that this positive streak will continue.

At his office, Raj lends a patient ear to every job seeker who comes with grievances. One woman who was facing paperwork issues with her sports quota appointment narrated her ordeal. She insisted on the RSSB chairman sending an email to the concerned department. In a calm yet authoritative voice, Raj promised to send the email. The woman left the room thanking him with folded hands.

“The RSSB has enjoyed a good reputation in the sense they conducted many exams before I joined. Just like any other organisation, it had some issues,” Raj said. Upon taking over as chairman, he identified paper leaks as a “major threat and fear” that had to be addressed on priority.

Dealing with routine bribery attempts, however, wasn’t something that he had anticipated. “Just a few days ago, someone came with a high-profile reference and wanted their marks increased in their answer sheet,” he laughed.

Beyond bribes, other issues demanded attention, including fake degrees, dummy candidates, and a lengthy exam timeline. But there was also a more amorphous issue: “Distrust among people that things don’t happen on time, and things were not systematised.”

The new chairman, an avid user of social media for exam announcements, is waiting to try out a new way of conducting exams—a mix of computer-based question papers with optical mark recognition (OMR) answer sheets. It will be a trial with small exams first. Raj said the “system is vulnerable” when it’s only an OMR-based exam, since the question paper changes many hands between being set, printed, transported to the government treasury, until its final destination at the exam centre.

“There are hundreds of hands handling the same paper,” he said, which a computer-based system will circumvent.

For now, Raj is ensuring that people are educated about the anti-cheating law.

“It’s been my endeavour to try and educate not only examinees but the invigilators, police personnel, exam centre staff and chaiwalas— anyone who is involved in the exam process,” he said. Raj is certain that his message has reached the “mafia and their aides”.

Meanwhile, across town in Gopalpura, Jaipur’s coaching hub, fresh graduates continue to pour in, eager to start the grind for coveted government jobs. Four friends—two women and two men—stand in a quiet lane, catching up with each other. The women started their classes last week, while the men attended it for a month. All four have come from Jodhpur and all seem confident that a fair fight awaits them.

“We are preparing to take the RAS (Rajasthan Administrative Service) exam. Paper leaks mostly happen in exams for lower-level jobs,” one of the women, Richa, said. “A strict law is there to check paper leaks. Also, we have a new government now. I don’t think any more leaks will happen.”

Nearby, a slightly older group stands at a tea stall. “They look so dejected, they might have been trying for years. They probably experienced paper leaks,” Richa observed. Her friend, who refused to divulge her name, interjected: “They probably didn’t study hard enough. We aren’t like them.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)