New Delhi: When Mathura town was gearing up for Holi celebrations in March 1998, death row convict Ram Shree was counting down the final days of her life, leaving behind her 18-month-old daughter. Her hanging was scheduled for 6 April. That was until she was saved by the bell. Or rather, by the belly.

Convicted along with her father and brother for the murder of four members of a “rival” family in 1989, Shree was sentenced to death in 1997. However, her case was taken up by several organisations, after news flashed that Shree– “mother of the suckling child”—was about to be executed.

The Supreme Court was quick to step in, staying her execution and overturning it in August 1998, after finding that her case actually did not fall in the rarest of the rare category, and awarded her life imprisonment instead. Her story now reads eerily similar to Deepika Padukone’s onscreen persona, Aishwarya, in Jawan. Dressed in a white saree, Padukone is led to the gallows, but she faints before the noose can be put around her neck. A quick nadi chikitsa–diagnosis through the pulse–revealed that she was pregnant. She got an instant but temporary reprieve from the death penalty.

However, Padukone’s character wasn’t as lucky as Shree. Aishwarya was hanged after her son turned five. While Indian law does allow reprieve for a woman on death row, having a child doesn’t always work in her favour.

There is a different kind of moral commentary that is happening when there is a female involved, says Shreya Rastogi

Only a handful of women face the death penalty in India, including 38-year-old Shabnam Ali who is often touted as the first woman who may be hanged in independent India. Although some media reports claim that one Rattan Bai Jain was the only woman to have been executed, back in 1955 for killing three girls.

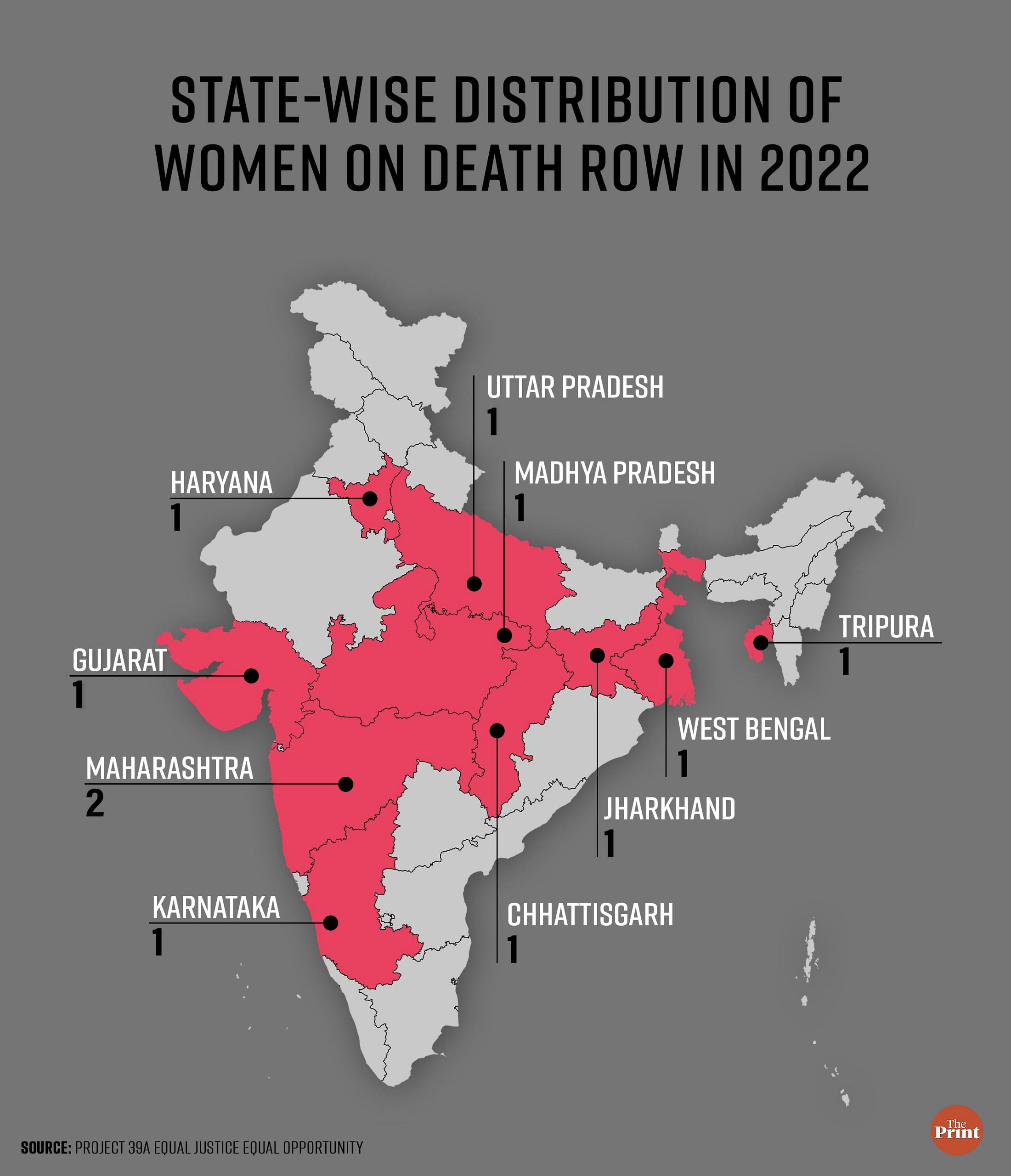

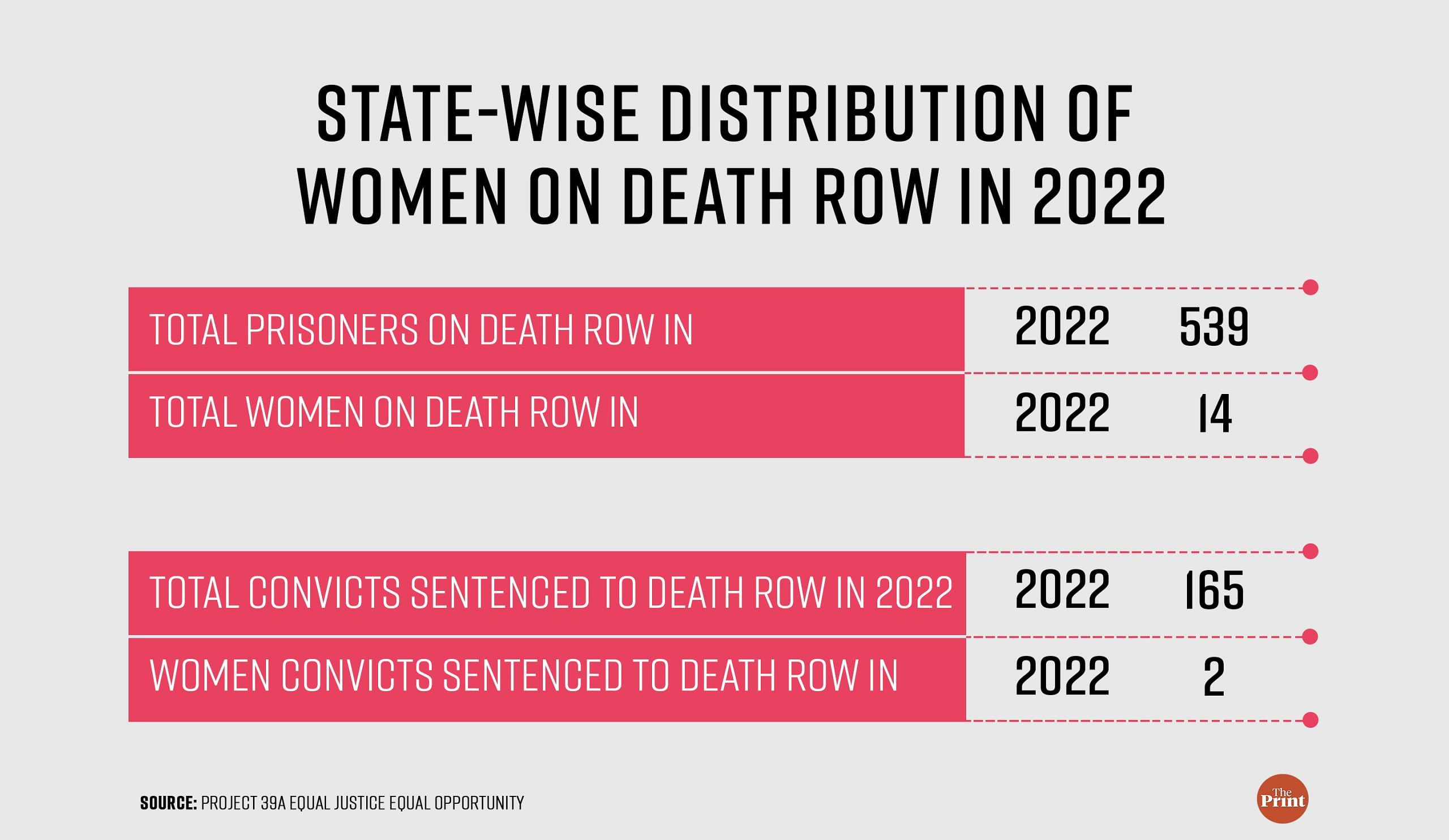

Out of 539 prisoners on death row, 14 were women as of 31 December 2022, according to the Annual Statistics Report 2022, released by the National Law University Delhi’s Project 39A in January this year. The death penalty numbers for women are similarly small across the world. However, research shows that a woman facing the death penalty is “judged for more than her crime” across the world. Courts judge women not only for their alleged offenses, but also for what is perceived to be their moral failings as “women” — for being disloyal wives, uncaring mothers or ungrateful daughters. And according to experts, a similar bias may be at play in India as well.

“There is a different kind of moral commentary that is happening when there is a female involved,” says Shreya Rastogi, Director of death penalty litigation at Project 39A. In a society that often finds women as the victim, Rastogi says that there is a “lot more anger for a woman as a perpetrator of offences”.

Women are seen as maternal beings, they are expected to be kind, gentle and respectful. Rastogi asks if this image plays into our perception when we see a woman offender.

“What needs to be explored is that do we give you the same kind of narrative about male perpetrators. Do men get discussed in the same way?” she asks.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan is the poster boy of reforms. Why is he shutting down factories in Jawan?

Pleading the belly

Padukone’s character, Aishwarya’s unborn son, Vikram Rathore, saved her from the gallows for a few years.

The Law Commission of India took up the subject of the death penalty in 1967. A state government, several high court judges, bar councils, MLAs and sessions judges had favored the exemption of pregnant women from the death penalty.

There is almost this rhetoric that how could you as a mother have done this, says Shreya Rastogi

Section 416 of the Code of Criminal Procedure says that if a woman sentenced to death is found to be pregnant, the high court shall order the execution of the sentence to be postponed. It adds that if the high court deems it fit, it could even commute the sentence to life imprisonment. But the law does not make a complete exemption for pregnant women– it only allows those women to live on borrowed time, unless the sentence is commuted, which is absolutely discretionary. And this leniency isn’t new. As per research, ‘pleading the belly’ used to be a common law practice dating back to the 14th century. A woman convicted of a crime and sentenced to death could have her execution stayed until she had given birth.

However, having a child is often a double-edged sword for women. “Sometimes it can be seen as a mitigating factor– that the child is dependent on the mother, and would need the mother. But it also acts as an aggravating factor, like in Shabnam’s case…There is almost this rhetoric that how could you as a mother have done this,” Rastogi says.

In such a scenario, being a mother works in women offender’s disadvantage. Rastogi says it “stems from how we view women”.

“Somehow for a man, that is never an argument– that he is a father, he shouldn’t have done that. So, it’s quite hypocritical that way,” she adds.

Nalini Sriharan, who was one of the convicts in the 1991 Rajiv Gandhi assassination case, also received a new lease of life because of her daughter. Sriharan was arrested in June 1991 when she was pregnant. She gave birth to a girl child a month later in jail. However, she was sentenced to death by the trial court in 1998, and this sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1999.

It was Sonia Gandhi who appealed to then President K.R. Narayanan demanding mercy for one of her husband’s assassins. Her plea hinged on one argument: Sriharan should be spared because of her eight-year-old daughter. Sriharan was then given a new lease of life when then Tamil Nadu Governor Fathima Beevi commuted her death sentence to life imprisonment in 2000.

Mothers and killers

No commentary on the death penalty in India is complete without reference to Ali’s case today. She was sentenced to death with her partner, Saleem, in 2010 for the murder of seven members of her family.

The incident dates back to 15 April 2008. A neighbour rushed to Ali’s house in Bawan Kheri, a village in Uttar Pradesh when he heard cries of “Bachao-Bachao Maare-Maare”. Inside, Ali was lying unconscious. She claimed that she had been sleeping on the terrace, and when she came down, she discovered her family had been axed at the neck by unknown people. On the first floor, seven bodies were found — Ali’s father Shaukat Ali, her mother Hashmi, her elder brother Anees, his wife Anjum, their 10-month-old son Arsh, her younger brother Rashid, and cousin Rabia. Arsh had been choked to death.

Ali was six weeks pregnant at the time of the incident, and gave birth to her son Taj Mohammad, months into her jail term in 2009. However, her case displays a similar condemnation of her failure to fit into the usual mold of a caring daughter. And in her case, having a child almost works against her.

While confirming her death penalty in 2015, the Supreme Court also spoke about a daughter being “a caregiver and a supporter, a gentle hand and responsible voice, an embodiment of the cherished values of our society and in whom a parent places blind faith and trust”. While dismissing Ali’s appeal, then Chief Justice of India HL Dattu said, “You (Shabnam) are also a mother. But you didn’t show any mercy or affection to your family. Even you killed the 10-month-old baby of your brother. We can’t grant any relief.”

Also read: ‘Blatantly erroneous’ — how 56 death sentences in 14 months defied latest Supreme Court guidelines

Katil Haseena

From Katil haseena (murderous beauty) to mastermind vishkanya to khooni saazish ke peechhe maasoom chehra (innocent face behind a murderous plan), the language used– inside and outside the court– for women convicts ranges from salacious remarks using personal details, to moral reprimanding.

“A woman by its very nature is merciful”-Punjab and Haryana High Court

Neha Verma, who was awarded the death penalty along with two others in 2013 for the robbery and murder of three women, was dubbed “katil haseena” in the media. In a 2018 judgment confirming the death penalty to one Sonal alias Sonu for the murder of seven of her family members, the Punjab and Haryana High Court spoke of how “a woman by its very nature is merciful”.

Another trend that Rastogi pointed out was the role of the co-accused in cases involving women death row convicts. She pointed out that in many of these cases, the co-accused is a male partner.

“This is something that people have tried to study, that what is the role that the male partners play in those cases, and is it that somehow the role of the woman in the crime gets overplayed or exaggerated, far more in sentencing, than the male actors,” she says.

Take the case of sisters Renuka Shinde and Seema Gavit, who were convicted for kidnapping 13 children and killing five of them between 1990 and 1996. They were sentenced to death in June 2001– with the court relying heavily on the testimony of Shinde’s husband, Kiran Shinde. Kiran was a co-accused before he was made the approver in the case and testified for the prosecution instead.

In his testimony, Kiran claimed to be a “silent spectator” to the crime. However, his role and his testimony were later questioned by the Supreme Court in 2006, when it noted that “Kiran Shinde was present when many of the murders had taken place and it is quite possible that he also must have been an active participant”. Despite this, the apex court noted, the public prosecutor did not take any steps to proceed against him.

The out-of-court, public narrative against Renuka Shinde reflected a gendered approach as well, according to Rastogi. “There was this kind of a narrative around Renuka and Seema– that you had your own children, yet you did this to others. But it was always about Renuka, it was never about Renuka and Kiran. And that is what I’m driving at,” Rastogi says. In January last year, the Bombay High Court commuted their death sentence to life imprisonment, citing delay in deciding their mercy petitions.

First woman to be hanged

Over the last two decades, only eight people have been sent to the gallows. These include the 2004 hanging of Dhananjoy Chatterjee who was charged and convicted with the murder and rape of a 14-year-old girl, 2012 hanging of Mohammad Ajmal Amir Qasab who was convicted in the 2008 Mumbai terror attack, 2013 hanging of Mohammad Afzal Guru for the 2001 Parliament attack case, 2015 hanging of Yakub Memon who was convicted in the 1993 Mumbai blasts, and 2020 hanging of the four convicts in the 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder case.

Only a handful of women have been given the death penalty during this time. Ali was sentenced to death by a trial court in July 2010 and has since been confirmed by the Supreme Court in 2015. Their review petition was also rejected in January 2020.

Her mercy petition is currently pending before the Uttar Pradesh Governor. And according to Ali’s lawyer, advocate Shreya Rastogi, Ali has a few remedies left. These include a mercy petition to the President, challenging the result of the mercy petitions in the court, as well as a curative petition in the Supreme Court.

The claim that no woman has been hanged in independent India is as arbitrary as the death penalty itself. This is because no authority in India seems to have maintained a list of people it has executed. A report released by NLU Delhi’s ‘Death Penalty Research Project’, released a list of prisoners executed in independent India, in an attempt to “move beyond the anonymity of numbers”. At the same time, it clarified that this list, with over 750 names, is not exhaustive and is not meant to be a reference for the total number of prisoners who have been executed in India since 1947.

This list was compiled as per responses received from central prisons in India. However, these prisons either provided the responses only for a limited period or did not have any records available, as per the report seen by ThePrint.

The Law Commission’s 35th report also provides some perspective on the numbers. The report was released in September 1967. Annexure 34 of the report contains state-wise tables on murder cases for the decade between 1954 and 1963. As per these tables, seen by ThePrint, there were over 1,400 executions in that decade alone, indicating that the number of people sent to the gallows in the country was much higher than what current numbers may suggest.

Also read: Are courts awarding too many death sentences? 539 convicts on death row in 2022, highest in 17 yrs

Cold-blooded women

The Law Commission also considered whether women should generally be exempted from the death penalty. It did not think that this was necessary because “a woman may be guilty of a brutal cold-blooded murder, and the case, therefore, may be one deserving the highest penalty of the law.” Of course, this statement was made before the Supreme Court, which considered the constitutional validity of capital punishment in 1980 in the landmark Bachan Singh case. The apex court emphasised the fact that courts need to consider much more than just the brutality of the crime.

“A female killer is more brutal and malignant than a male murderer”

The Law Commission had, in fact, sent out a questionnaire with a question of whether “certain classes of persons should not be punished with death, e.g., children below a particular age, women, etc.?” In response, several stakeholders opposed any exemption to women, “because some of the most cold-blooded murders are committed by women out of jealousy, desire for gain or vengeance”. One high court judge said that “the heinousness of a crime is not reduced merely by the fact that it is committed by a woman and that there have been numerous cases in which women have been found guilty of murdering their husbands in cold blood”.

Responders, in fact, got poetic while demanding equal penalties for women. A senior member of the Bombay Bar told the commission that “a female killer is more brutal and malignant than a male murderer”.

“It is not merely in fiction and drama that female friends of the type of Lady Macbeth commit or abet diabolical murders,” they added.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)