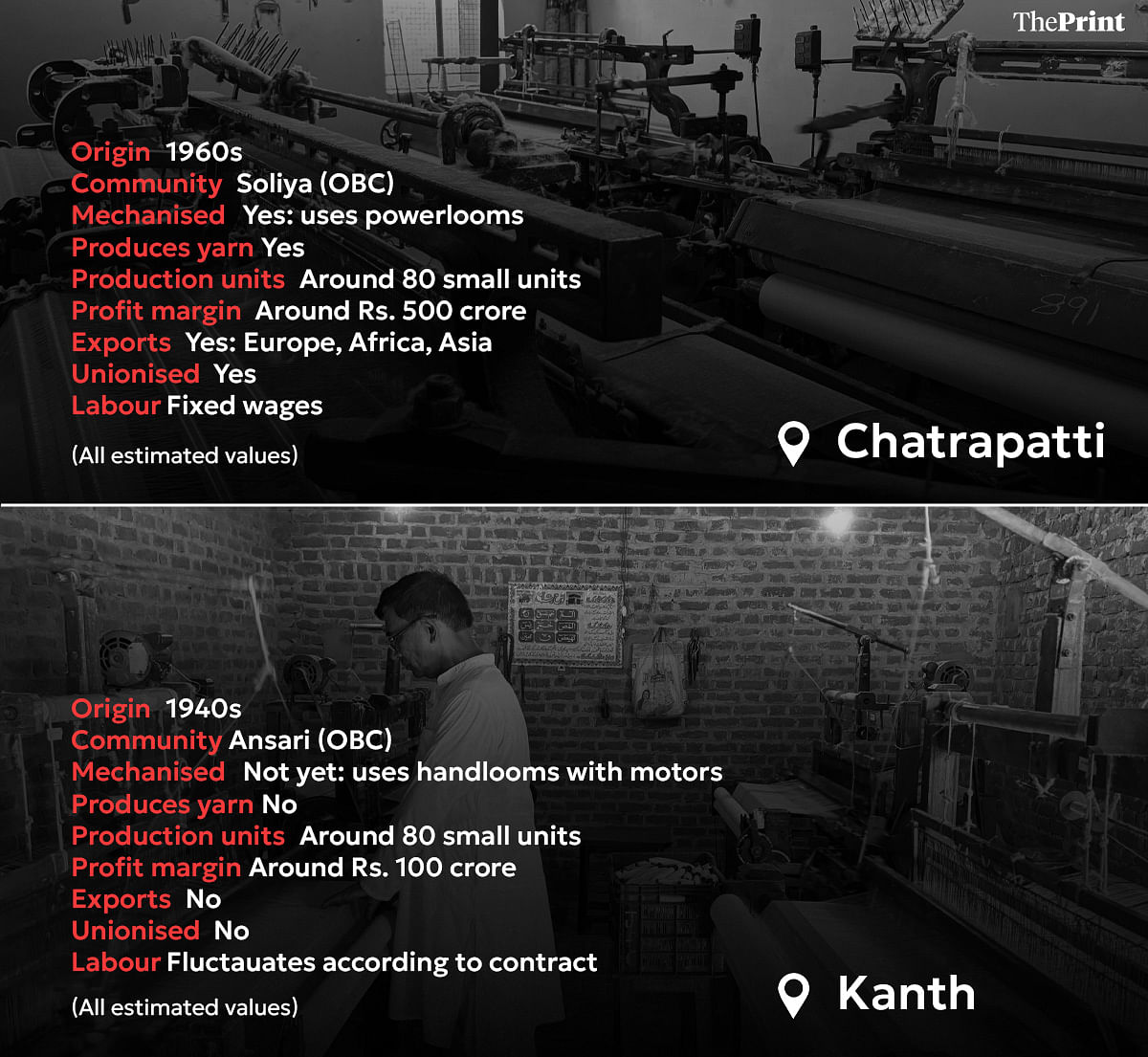

Madurai/Moradabad: Nothing irritates the bandage businessmen from the tiny Tamil Nadu village of Chatrapatti as much as hearing about the distant town of Kanth in Uttar Pradesh. Kanth and Chatrapatti, at the opposite ends of India, were built on a common business—both are home to the microenterprise of weaving hospital bandages.

But the twin MSME hubs of bandage-making in India can’t be farther away from each other—in geography, business practices and growth. Kanth is in the industrially laggard Uttar Pradesh and Chatrapatti is in Tamil Nadu, one of the most industrialised states in India. How the two came into the bandage business, which community dominates the manufacturing, and how it is prospering is a telling tale of the proverbial north-south divide and the political economy of India.

The differences also hold lessons for India to evolve a best practices template for MSMEs and generate employment and exports in PM Narendra Modi’s ambitious Make-in-India endeavour. Especially as UP CM Yogi Adityanath attempts to shake up the state’s industrial climate.

In one state, bandage-manufacturing is a form of social mobility for the traditional community of weavers. In the other—it’s almost a trap. They are microcosms of their home states.

In both states, one particular community — the OBC group Soliya in Tamil Nadu and the Muslim OBC group Ansari in Uttar Pradesh — dominates the business. And both say that Chatrapatti’s industry is superior. The differences, however, are far more stark — from infrastructure to quality of life to the development of the region and its people.

While Kanth produces bandages at cheaper rates and casts a wider net across India — selling even to Kerala, Tamil Nadu’s neighbouring state — Chatrapatti is smaller and is known for higher quality products, which it exports to countries such as Germany, France, South Africa, and Australia.

Chatrapatti’s bandage industry emerged at least two decades after Kanth but it is better organised and is more lucrative. The two compete but also collaborate – Kanth now buys yarn from Chatrapatti weavers.

“In Chatrapatti, weaving is cheap but the after-weaving costs — like labour and packaging — are high. In Kanth, weaving is expensive but after-weaving costs are cheaper,” explained Sourabh Agarwal in his air-conditioned Sree Jee Bandages office in Kanth. “Kanth is an older industry but Chatrapatti is a more advanced industry.

“UP hasn’t gone beyond sweatshop capitalism,” said Harish Damodaran.

The two towns are synonymous today with hospital bandages. Chatrapatti regards itself an offshoot of its hosiery export hub of Tiruppur and calls itself ‘the Bandage city’. Many in the Muslim-dominated Kanth, now a municipal council, prefer to call the industry the healer of India’s wounds.

And in many ways, the industry’s growth and capabilities are shaped by the state they’re in. Kanth – despite its old ways of manufacturing compared to Chatrapatti—enjoys a distinct price advantage over Tamil Nadu’s bandage industry.

“Compared to Kanth and Moradabad, our village is far superior. But they’ve been in the business longer and are giving us extremely tough competition because their product is cheaper,” said N. Senthilraj, President of the Surgical Dressing Manufacturers Association, the din of looms a perpetual background score to every conversation. “What we sell at Rs. 10 they sell at Rs. 7.”

The price differential represents the gulf that exists between both industries, the two states and the communities that run them.

“UP hasn’t gone beyond sweatshop capitalism,” said Harish Damodaran, journalist and author of India’s New Capitalists. “The labour in UP is probably more skilled—every town and cluster has its own secret on how to produce their speciality. But there’s no modernisation and instead of the government focusing on their inherent strengths, there’s indifference. Whereas in Tamil Nadu, everything is of better quality because they’ve moved up the value chain.”

International vs domestic markets

“There’s no other work here,” said Selvaraj, in Chatrapatti. “Only bandages!”

The sound of clattering looms echoes through Chatrapatti. Large swathes of white cotton being dried on terraces is the signature look—only rivalled by the sight of a temple on every street.

P Selvaraj, the 44-year-old owner of Vijaya Textiles, surveys his contracted workers operating a set of power looms churning out yarn. It’s technically a holiday — the start of the Tamil month of Aadi — but in Chatrapatti, the looms rarely fall silent.

“There’s no other work here,” he said. “Only bandages!”

Not only has the town grown from handloom to power loom, there is also a visible generational mobility.

Around 50 years ago, each and every house in Chatrapatti had a handloom. Selvaraj’s parents would weave bandages in their home. It was only in 1986 that his father began expanding to other products — like weaving the cloth lining often used in courier envelopes. The business was doing well enough to send Selvaraj to get his BSc in textile technology, before he returned home to become an entrepreneur and set up his own company.

Today, he has several powerloom owners weaving cloth for him, which he buys from them before bleaching and cutting to various size specifications and then packaging for sale. He estimates that 60 per cent of the town is connected to the industry.

Selvaraj speaks fluent English, besides Tamil and Hindi — a language he picked up to interact with businessmen from Uttar Pradesh. He’s a member of the Lions Club, and has taken elocution classes in an attempt to upskill. It’s a character trait in Chatrapatti that has led to a rise in entrepreneurial spirit: several of Chatrapatti’s business owners are members of the Rotary Club, which is active in the tiny village.

It helped them to network with other businessmen, and was especially useful when the village was exporting bandages to countries like Germany, France, Italy, US, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Sri Lanka. Then came China.

These exports have slowed down since 2005, when China’s market grew. Countries like Nepal, Maldives, Angola, Kenya, Peru, Papua New Guinea, Madagascar are among the largest buyers today, according to the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises.

However, Data from the ministry shows that the bandage industry exports grew from Rs 324 crore in 2017-2018 to Rs 407 crore in 2020-2021.

Chatrapatti’s industry traces its origin to the larger textile belt of Rajapalayam, Coimbatore and Tiruppur. Weaving bandages was a natural transition for the Soliya community, an upwardly mobile OBC group.

The man who upped the ante was Palani Vinayakan, who started manufacturing bandages with power looms in the 1970s. The mechanised looms that ushered in the industrial revolution at the turn of the 19th century changed the way Chatrapatti’s weavers worked in the 1980s. Handlooms were phased out. Productivity was increased. At first, the weavers of Chatrapatti were supplying to societies like Tamil Nadu cooperatives, but slowly scaled up to supply hospitals and businesses in metro cities, and then to Tier-2 cities.

And then they turned their gaze beyond India’s borders. What really helped the industry take off was the presence of four international exporters: Naachiyar, Arumugam, Premier and Rajshekhar Exporters.

It expanded Chatrapatti’s horizon to foreign lands. Quality of the product became the focus. But now, 50 years after Vinayakan’s power loom revolution, the Tamil Nadu village is facing a new challenge because of China. It’s a tough competitor, and after the Government of India introduced a new set of Medical Devices Rules in 2017, exports have experienced a huge slowdown.

“With the new rules, it’s harder to get licenses to sell our various products. This has made things more expensive and there’s more paperwork,” said Selvaraj.

Business owners in Chatrapatti estimate that roughly 10,000 people are employed in the industry — 80 manufacturers churn out fabric, and around 45 manufacturers have licences to sell medical products. The net result is an industry that makes around Rs. 500 crore a year.

Now, most of the business is domestic. And this is where Kanth comes into the picture.

Fight for yarn, electricity

Nearly 3,000 km up north from Chatrapatti, Naved Ansari of Perfect Surgicals has just picked up his children from school on a sleepy afternoon in Kanth. He runs a family business. His company was started about 60 years ago by his grandfather, and the business is doing well. The 35-year-old runs it with his two brothers, and the entire family lives together in a cramped home in a largely Muslim neighbourhood beyond the Moulana Abdul Dwar in Kanth.

It can be any non-descript, dust-blown north Indian town – with open drains and clogged streets with an overhang of a maze of electrical wires.

The industry in Kanth was started by weavers — the Bunkar community, ‘bunkar’ literally means one who weaves — moved to the region from Gujarat to set up shop in the 1940s. By 1955, it was a flourishing market.

The first licensed manufacturers started producing at a large scale in Kanth in the early 1960s. And today, it has grown to plug gaps in the domestic market.

Ansari holds a Master’s degree in commerce from Moradabad. He has witnessed Kanth’s growth around him, and while the industry grapples with the challenges of electricity, and an inability to make a quantum leap in business processes, his main grouse is that the raw material for bandages — cotton yarn — is hard to come by since major yarn mills in north India have been shutting down. He sources his yarn from whoever comes to sell it at the local mandi,or buys it on IndiaMart.

He has heard of the south Indian rival, but he’s only interested in Chatrapatti as a potential place to buy yarn.

“Chatrapatti’s quality is better,” shrugs Ansari as he digs into a plate full of dates from Saudi Arabia.

The gulf between business owner and worker is far, far wider in Kanth than in Chatrapatti, where labourers often graduate to become owners by the next generation. Ansari’s family is now wealthy, but the number of weavers he buys from has dwindled. The lives of the remaining weavers have not improved much, and Ansari is not surprised that the younger generation is considering other options outside of the bandage industry.

The main problem is electricity, he explained. “Electricity here is very expensive, and very irregular. So, people are unable to weave. We buy cloth, get it bleached, cut it, and then sell it across India — mostly to Punjab, Uttarakhand and Haryana.”

Because of this shift in the industry, many in Kanth have moved on to selling readymade textiles because there’s more money to be made there. It’s getting difficult to weave bandages, according to Ansari, and labour is hard to come by.

“But I would never leave Kanth,” said Ansari. “Why would I? It’s where I belong, where all my memories are.”

Two streets down, Mohammed Shariq is counting cash at his desk. His factory is a buzz of activity, and he’s directing labourers on which products to load onto a tempo truck.

“That industry is ahead of us,” he said, referring to Chatrapatti. “Things are cheaper here but it’s a larger, more organised set-up there.”

This is reflected in how much profit the industry is making: Chatrapatti is estimated to be making around Rs 500 crore, while Kanth makes Rs 100 crore.

There are around 20 other big businesses in Kanth, like Ansari’s Perfect Surgicals and Shariq’s Premier Surgicals, with several others choosing to exit due to lack of greycloth — the raw material which is bleached white before it becomes a bandage — and expensive electricity. Nearly every business owner here agrees that Chatrapatti’s industry is more advanced than them — and both industries know exactly why.

“Kanth is competing with us but also purchasing with us. That’s because they don’t have the infrastructure to grow their business in this day and age,” said Selvaraj.

How geography affects industry

“There’s no life in thread,” said Jaffer, bandage weaver in Kanth.

Every Monday, the town of Kanth gathers at the local square to attend the mandi (market).

For 62-year-old Mohammed Jaffer, it’s the most important day of the week — because that’s when he sells the clothes he’s been spinning all week. People like Jaffer are a few rungs below businessmen like Ansari and Shariq, and completely dependent on them for the sale of their product.

Jaffer moved from weaving on a handloom in his home — it was too noisy for his wife — to a small piece of land he bought eight years ago. He now operates two handlooms with motors attached to them — a far cry from the mechanical powerlooms found in the smallest of homes of Chatrapatti.

While Chatrapatti is thinking in terms of technology, Kanth relies on tried-and-trusted tactics of jugaad.

When there’s no electricity, which comes in unpredictable short bursts for around six hours a day while he works, Jaffer has no option but to use the handloom manually. He’s not in debt, but he’s not making any profit either: whatever he earns, he spends immediately.

He works with his son, and can’t afford to hire any other labour. His other son is a tailor. Both of them failed high school, while Jaffer didn’t go to school. All his documents — including the deed of his workshop — are in his wife Raisa Khatoon’s name, because women get better subsidies from the government than men. She doesn’t work, and tends to their home, which is a 15-minute walk from Jaffer’s workshop.

The breathless buzz of business is missing in Kanth. It is unmissable in Chatrapatti. There is a sense of stoic despondency here.

“There’s no life in thread,”Jaffer smiles, wiping sweat off his brow. The electricity has been gone for a few hours, and so he reclines on a charpai in the small yard outside.

“Ever since I’ve opened my eyes, I’ve seen weaving being done in Kanth. It’s been going on since before Independence. But somehow, life for us weavers isn’t improving,” he said.

Outside his little brick hut sits an elderly woman, who spins yarn on a charkha for even less.

While Jaffer admits that power supply has been more reliable and consistent since Adityanath took over as CM in UP, he is particularly incensed by the high cost of electricity. He recalls a local official accusing him of not paying his arrears, presenting him with a bill he couldn’t read. The memory is seared in his mind because the official allegedly abused him, denigrating him for not paying. Ultimately, it turned out that the official was looking at someone else’s bill— Jaffer had used far less and had no arrears to pay.

“The electricity metre never lies!” said Jaffer, just as the power came back and a tiny lightbulb in the workshop flickered on.

Upward mobility in Chatrapatti

The main differences between Chatrapatti and Kanth boils down to three Es–electricity, equipment, and education levels.

The high cost of electricity in Uttar Pradesh is not mitigated by irregular hours. While electricity prices were also recently hiked in TN, the quality of power the village receives is better than UP.

What rankles the most is the upward mobility this business has offered the people of Chatrapatti. B Sivaraj, 42, started weaving in 1996, working for a powerloom set owner who would then sell to businessmen like Selvaraj. His father used to weave bandages too. In 2002, he took a loan from a rural bank and bought his own set of powerlooms — one set equals eight looms, which requires two labourers to manage four looms each. He recruited his wife Murugalakshmi, and the two of them would work about 12 hours each day. Now, he’s earned enough to hire two Dalit labourers to work for him.

While he didn’t go to school and his wife studied until class 8, one daughter is in school, while his 21-year-old is doing her BA in Tamil at a college in Tiruchirappalli.

“Once I learned how to use powerlooms, I wanted to start my own business and make money,” said Sivaraj. “I know only bandages. I don’t know any other work. Even if I try to leave, I don’t know what other work I could do — but I learn about the world from my daughters and what makes them excited,” said Sivaraj.

A recent pastime for him has been going to Rajapalayam to watch English movies dubbed in Tamil, which his daughters enjoy.

Like Jaffer, Sivaraj too has cleared all loans and bought a small house 15 years ago. But he makes significantly more money than Jaffer — while Jaffer’s wages is tied to however much he’s able to weave and the competitive price he can sell it at, Sivaraj is guaranteed around Rs 12,000 a month after paying his labourers.

Selvaraj estimates that a powerloom produced enough cloth to make Rs 50,000 in sales a month. He estimates the number of powerlooms in Chatrapatti at 7,000.

“That’s a good amount of money that the village is making,” he said, attempting to do the mental maths.

“Labour is unionised in Chatrapatti, so wages are uniform. Here, wages are not uniform — so the profit that each owner takes is variable. Things are more manual here, and cheaper here,” said Shariq in Kanth.

This entrepreneurial spirit exists across the village of Chatrapatti, which is geographically much smaller than Kanth. And while electricity is expensive in Kanth, water is expensive in Tamil Nadu. Still, bills paid, the average labourer earns more in Chatrapatti than in Kanth, estimates Shariq — contracted labour working on the factory floor make between Rs 500 and Rs. 800 a day in Kanth.

“Labour is unionised in Chatrapatti, so wages are uniform. Here, wages are not uniform — so the profit that each owner takes is variable. Things are more manual here, and cheaper here,” said Shariq in Kanth. Overall, it does even out, given the price of water and electricity, but the average labourer in Chatrapatti will earn more while the average business owner in Kanth earns more.”

Differences in equipment also lead to different costs of production. While businesses in Chatrapatti use expensive machinery to cut the bandages to different sizes, businesses in Kanth use knives as a cheaper alternative. The bleaching in both places is done with peroxide — but while businessmen in Tamil Nadu can afford special facilities, many businesses in Kanth are used to bleaching in water bodies, which has polluted the water in the region. And since the industry is at the micro level, there’s no capacity to set up Sewage Treatment or Effluent Treatment Plants.

And Shariq concedes that better education and technical skills plays a role too. He feels that the drive to upskill and improve is lacking in Kanth.

Salim, another labourer in Kanth, let his son drop out of school in class 9 in 2018. He now works for another business in town, transporting products and driving trucks. In contrast, 60-year-old Rajeshwari in Chatrapatti, who was herself educated only through class 5, has bought 16 looms over her 30-year-career and her son is now an engineer working in Madurai. She employed five people to work the looms for her — one of them, Selvakumar, didn’t go to school, but both his boys are enrolled in a local English-medium school in Rajapalayam.

“The real problem is that there is a lack of technical education,” said Agarwal, Kanth.

“The 1980s were the turning point for our village,” said 64-year-old K. Kanakarajan, owner of Vijaya Textiles in Chatrapatti. “Before the 1980s, not everyone was educated. Most people had homes with asbestos thatched roofs. Now everyone is educated, until at least class 8 or 10. And after 2000, I can say that 80 per cent of all homes had toilets.”

The workers here have taken advantage of government schemes like the Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprise, through which credit lines are extended by banks.

“The market culture that exists in Chatrapatti is also here in Kanth, but to a smaller extent. There are a few people who have grown with time and become owners after being workers,” said Agarwal. “But the real problem is that there is a lack of technical education.”

A technical university was set up in Kanth as part of the Kanth Kaushal Vikas. It offers courses on plumbing and masonry, but not one course on weaving.

“When this is the main industry here, it should offer at least one course on weaving or business management,” said Agarwal. “That way, people can upskill and at least invest in better equipment to sell better quality products and grow their own businesses.”

Growth of the industry

The year 2017 was pivotal for the bandage industry. It was when the Ministry of Health released the new set of Medical Devices Rules.

“The central government needs to make it easier to get licences, and also check how many unlicensed products — which are bad quality — are entering the market,” said Surgical Dressing Manufacturers Association president.

Even though bandages are technically woven cotton, they are classified as a Class B medical device. The new regulations were a huge setback, as existing businesses had to re-apply for medical licences from BIS, Drug Controller General of India, New Delhi, and obtain NABL accreditation. Businessmen in Chatrapatti complain about rampant unlicensed work in Kanth, while those in Kanth complain of rampant unlicensed work in nearby Meerut.

“Chatrapatti industry has been stagnating since then,” grumbled Surgical Dressing Manufacturers Association president Senthilraj. “The central government needs to make it easier to get licences, and also check how many unlicensed products — which are bad quality — are entering the market.”

The Surgical Dressing Manufacturers Association estimates that around 35 manufacturers have left the industry since 2017.

Bandage cloth is one of 358 items the government procures from micro and small enterprises. It’s helped the industry streamline manufacturing capabilities, and guarantees a fixed source of consumption. Kanth dominates the domestic market, with local manufacturers winning government tenders to supply to medical colleges and government hospitals. On the other hand, Chatrapatti has had to apply for licences and expand to related products like gauze, surgical tape, and other such products.

The classification of bandages as a medical device and not as cotton is a sticking point in Kanth. While weavers in Varanasi get a 70 per cent SGST tax rebate, the weavers of Kanth do not — because they are not weaving wearable cloth, but bandages.

“The main point of difference is that micro industries can be quite primitive in Uttar Pradesh — even though the labour might be more skilled. In Tamil Nadu, there are more modern facilities,” Damodar

In 2020, the Ministry of MSME estimated that the market size of the medical textile industry was between Rs 4,000-5,000 crore. The major growth drivers of this segment, according to the same document, include the rising demand for primary wound dressing materials, the use of smart textiles, an increasing number of surgeries, and the growth in disposable income, which has improved accessibility and awareness with regard to ageing, personal care, and hygiene.

Uttar Pradesh is known for its little clusters of products spread across the state — perfumes in Kannauj, leather in Kanpur, handloom textiles in Varanasi, locks and hardware in Aligarh, electronics in Noida.

But such clusters haven’t always been nurtured, explained Damodaran. For example, while abattoirs exist in Uttar Pradesh, tanneries have been shut down — which is why leather hubs like Agra and Kanpur have to send products to tanneries in other states. In contrast, leather hubs in Tamil Nadu like Ambur and Dindigul have tanneries which helps the industry sustain itself. The same story is found across other handloom hubs in both states like Varanasi and Kancheepuram.

“The main point of difference is that micro industries can be quite primitive in Uttar Pradesh — even though the labour might be more skilled. In Tamil Nadu, there are more modern facilities,” said Damodaran. He pointed to how infrastructure plays a role too: good highways bring about connectivity, and ports in Tamil Nadu make it easier to export. Plus, producing for exports also automatically improves the standard of the product.

In Tamil Nadu, which is known for big industries, decentralised industrialisation has also led to similar, new clusters. This has actually helped propel the state forward, a formula that UP hasn’t yet cracked due to the same regional factors that have held back its bandage industry.

“TN’s economic transformation has been brought about not by so-called Big Capital as much as medium-scale businesses with turnover range from Rs 100 crore to Rs 5,000 crore…Its industrialisation has also been more spread out and decentralised, via the development of clusters,” writes Damodaran.

“There’s a lot of skill formation and learning that happens when you have cluster-based industrialisation,” said a member of Tamil Nadu’s State Planning Commission.

The advantage that MSMEs offer, in this regard, is mobility for workers. And a distinct advantage Tamil Nadu has over UP is that it has heavily invested in skill development programmes.

“If you want to build an industry with a robust ecosystem, then embedding production in the local economy whereby learning takes place is important. There are better prospects for Ancillary industries to emerge in the region as a result,” said M. Vijayabaskar, a member of Tamil Nadu’s State Planning Commission and a professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. “There’s a lot of skill formation and learning that happens when you have cluster-based industrialisation. It creates local economic linkages which is not just about employment, but also about getting multiplier effects.”

The role of community

Over the last 20 years, Sree Jee Bandages’ Agarwal has visited Chatrapatti nearly 10 times. The four-day long journey would take him from a train to Delhi, to another train to Chennai, and a third train to Madurai or Rajapalyam. After that, Chatrapatti was only a short bus ride away.

He wasn’t going on a vacation, or to visit temples. He was going to scope out the competition, what they have to offer, and who runs them.

The labour that dominates the bandage industry in Chatrapatti and Kanth are Soliya and Ansari respectively. While both Soliyas and Ansaris are OBC, they occupy very different spaces within the sociopolitical caste fabric. Chatrapatti is in a state where the OBCs have both political capital and representation — while the Muslim Ansari weavers of Kanth do not.

Over time, the MBC Thevar community has started entering the market in Chatrapatti, with the older, traditional Soliyas begrudgingly making space for them. Dalits are mostly hired as loaders.

In Kanth and Moradabad, meanwhile, the industry is still very much dominated by Muslim labour — comparatively shrinking as people exit the industry to enter readymade textiles. It left a larger share of the market open for businesses like Naved Ansari’s Perfect Surgical to acquire.

“Only 20 per cent of the town is employed in bandage industry today. Readymade textile is doing better these days,” Shariq

The lack of organisation has also led to Kanth’s industry to be more diffused, dispersed across older businesses that have managed to stay in the game, relying on the backs of labourers like Jaffer who remain at the same level they started. In Chatrapatti, an entrepreneurial spirit infused with social mobility has allowed newer generations of businessmen to stake their own claims, paving the way for the next generation to move ahead.

“Our villagers started their lives as weavers. After working for several years, they take out a loan, buy a set of powerlooms, then sell to exporters. This way, even if they don’t have any direct business, with a powerloom they will be able to sell to a market,” explained Selvaraj.

Shariq said it’s not really the same situation in Kanth, where the industry has seen a larger exit of labourers because of unequal wages and the lure of higher paying jobs.

“The product sells, no matter what. But it should be better,” he said, in between issuing orders. “People need to be technically skilled. The industry is definitely slowing down on the labour basis — only 20 per cent of the town is employed in this today. Readymade textile is doing better these days.”

Despite being dominated by Muslim labour, the largest factory manufacturing bandages in Kanth isn’t run by Muslims: it’s Shree Jee Bandages, run by Sourabh Agarwal and his wife Shilpi Agarwal.

“So much of the industry depends on location,” said Agarwal. “If the government supports the community here and shares knowledge, Kanth’s capacity can increase by five times.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Articles like these are why I subscribe to The Print!

Keep up the good work.

Thanks for an insightful, unbiased and factual analysis.

excellent, well researched and in depth. Very contrasting stories of two towns

This type of content is real journalism. Great work! Keep it up. Looking forward to such mini stories/docu type content which is non political but more socio-economics.

Excellent article!

The things needed for successful business seem so simple, in electricity and education and equipment. It is sad that GoI can’t yet provide these basics to rural India.