Kohima: Nagaland has a new desire. To become a medical hub like Tamil Nadu. Vellore is the new dream in Kohima. And the brand new 120-acre medical college, the first in the state, is the starting step.

While JCBs claw clumps of earth to make space for new buildings, lectures have already started in the academic block at the newly inaugurated Nagaland Institute of Medical Sciences and Research (NIMSR) in Phriebagei, just 20 minutes from capital Kohima. The imposing three-storey building, painted in white with blue-tinted windows, opened its doors to 100 students in September.

Around 30 students in white lab coats pay close attention to their physiology professor. “Who can give blood to anybody?” he asks. The professor answers the basic question himself (O negative) before moving on, while students scribble notes. A spacious examination hall, with sparkling tiled floors and spotless white walls, doubles as their classroom for now.

Nagaland has finally gotten rid of the dubious distinction of being the only state in India without a medical college. Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram were the last to get their medical colleges in 2018, while the oldest one in the northeast — Assam Medical College and Hospital in Dibrugarh district — came up in 1900 after a donation by British surgeon Dr John Berry White.

This college is a very precious one for the state of Nagaland. They got it after 60 years of statehood. They never even had a private college

-Dr Soumya Bhattacharya, dean, NIMSR

At NIMSR, the classrooms may be under-prepared, makeshift, and students are still settling in. The infrastructure is still catching up with their new aspirations but a medical college, they say, isn’t just about education and jobs. It has immense potential to launch unexpected windfalls in public healthcare, promote research, and improve doctor-patient ratio.

“This college is a very precious one for the state of Nagaland. They got it after 60 years of statehood. They never even had a private college,” said NIMSR’s dean and director Dr Soumya Bhattacharya, who is from West Bengal.

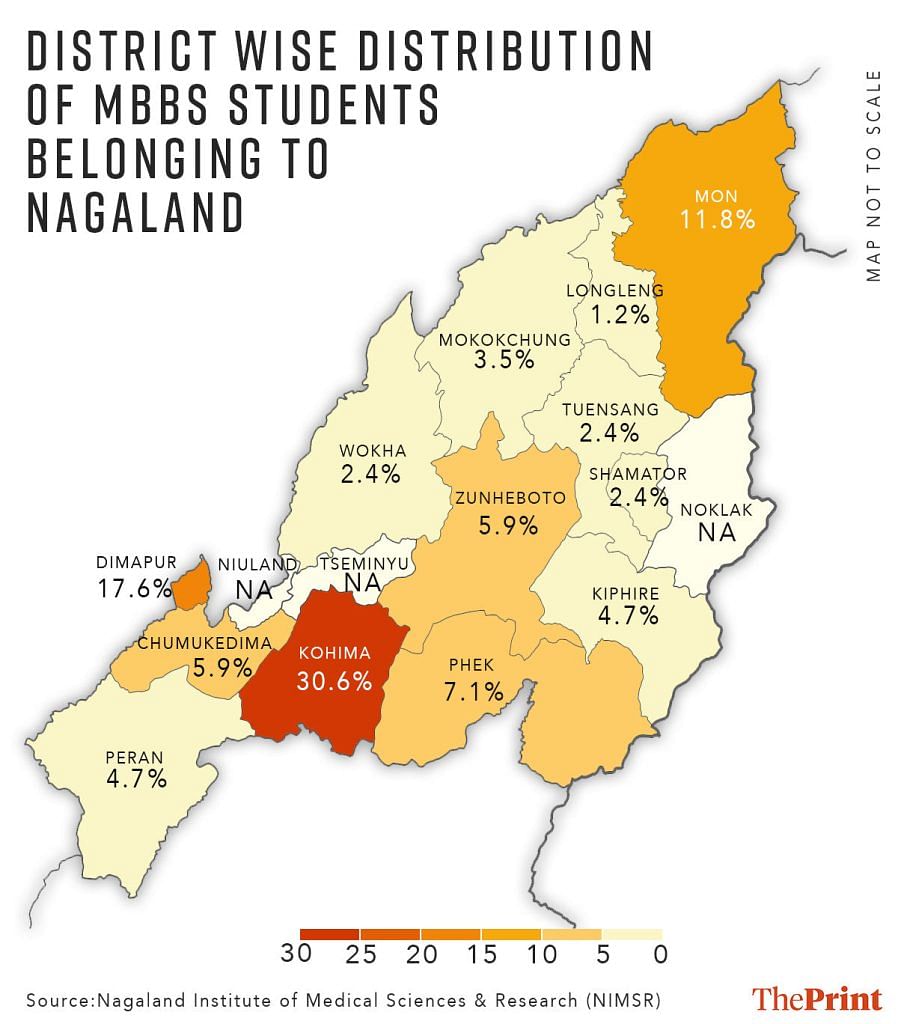

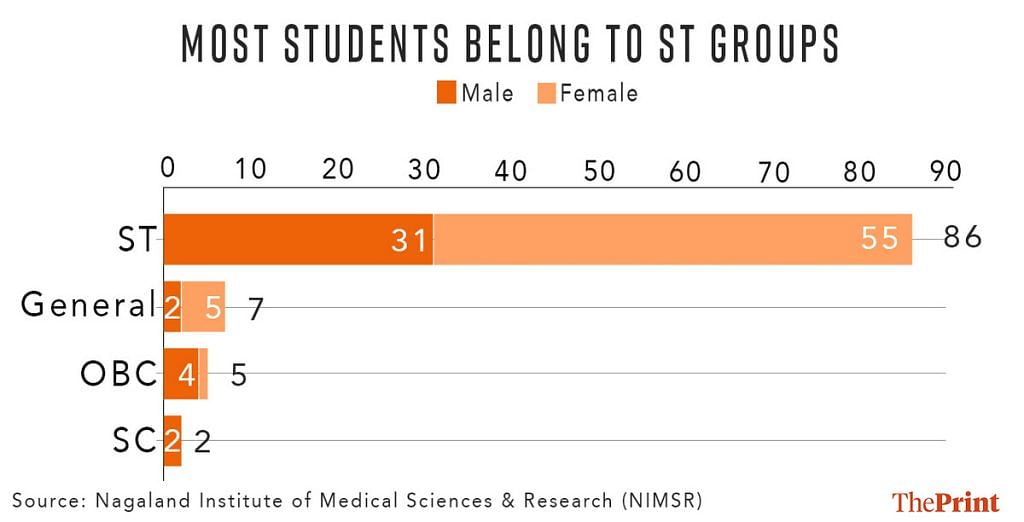

NIMSR began classes from 1 September, taking off at full capacity with 100 students. A majority of them (85) belong to Nagaland’s 17 tribes and have come from Kohima, Mon, Phek, Wokha, and other parts of the state.

The birth of NIMSR mirrors the essence of the tiny northeastern state — hardworking people filled with joie de vivre, challenging terrain, and the lingering effects of protracted insurgency on the administrative machinery.

Only one building is ready so far, but construction work is underway at a frenetic pace across the vast campus. Roads are being made and workers are clambering up and down skeletal frames of buildings that will one day be new laboratories, lecture theatres, a central library, and research centres.

After lunch, Ricka* takes the dirt road from her hostel to the academic block for afternoon classes. She’s thrilled to be part of the first batch of Nagaland’s first medical college but worries constantly about the lack of infrastructure.

“We don’t have WiFi here. Even the mobile network is not good. There’s one spot in the hostel where the signal is strong. We take turns to use the space,” Ricka said.

Lectures are taking place inside temporary classrooms, laboratories are awaiting final touches, and instruments and equipment are yet to be installed. The library is still being built.

“There is apparently a [provisional] library in the sports complex, but we still don’t have access to it,” she said.

These teething problems will be fixed, said the dean. Nobody in Nagaland—not the government, administration, or its people—wants their first medical institute to fail.

Also Read: Hindi engineering courses in MP are just not taking off. Students keep moving to English

A decade of delays

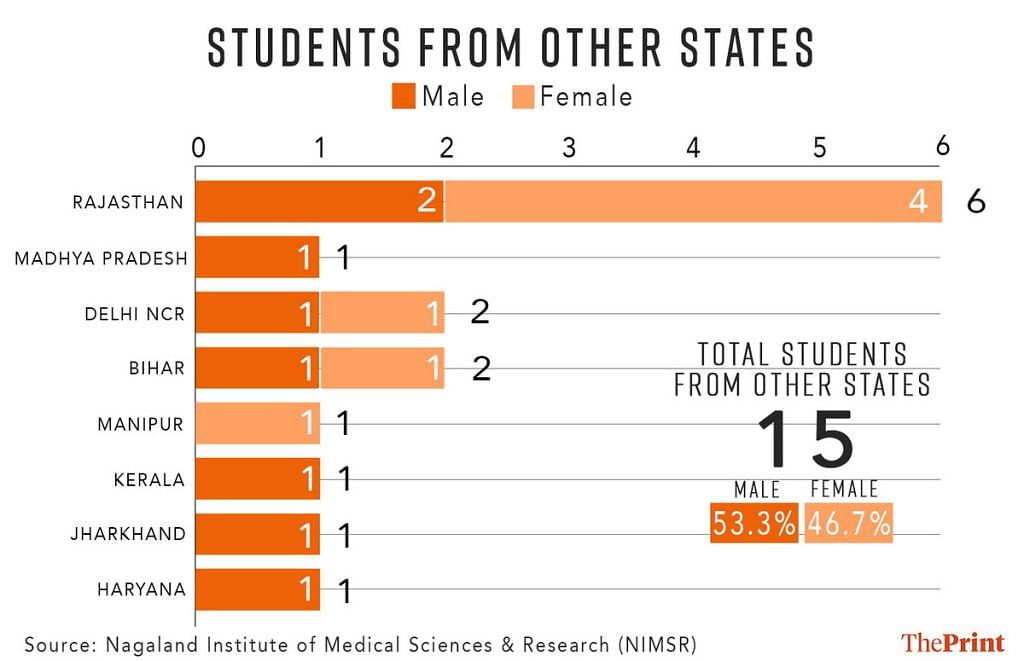

Until now, Nagaland’s medical aspirants had to make do with 63 seats reserved for them in colleges across India, including 21 in the northeastern states of Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura. At NIMSR, 85 of the total 100 seats are available to them, with the remaining 15 reserved for students from other parts of the country.

The new medical college has afforded Vitokali Chishi from Dimapur the opportunity to become a doctor—something she hadn’t considered before.

“If I was not in NIMSR, I’d be doing a Master’s in nuclear medicine. I happened to take the exam [NEET] and by God’s grace I got through,” she says. Vitokali completed her Bachelor’s in radiology from Punjab, but for an MBBS degree, she’s willing to go back to the basics even if it means lost years.

“I’m starting again as a college student. It’s still exciting and thrilling so far.”

NIMSR was conceived nearly a decade ago, but a series of unfortunate events, both natural and man-made, put a spanner in the works.

In February 2014, the UPA government gave its nod for a medical college, sanctioning Rs 189 crore toward it with a funding ratio of 90:10, where the Centre provided a larger chunk of the cost.

The project took nearly 10 years to take off, reflecting the widespread administrative sluggishness in Nagaland, likely stemming from pervasive corruption. Earlier this year, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) flagged rampant anomalies in various state departments.

With the financial, emotional, and mental energy required to set up a medical college in the northeast, one can open three other medical colleges elsewhere

-NIMSR faculty member

The medical school finally coming to life sheds light on the complexities of bringing a project to fruition in this part of the country.

“With the financial, emotional, and mental energy required to set up a medical college in the northeast, one can open three other medical colleges elsewhere,” said a faculty member who previously taught in Punjab, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The state government had to battle hurdles unique to Nagaland, starting with the acquisition of land for the project.

In Nagaland, the land-holding system is different from the rest of the country. “The land belongs to the community. It doesn’t belong to the government,” said Dr Kika Longkumer, the nodal officer from the health and family welfare department who was appointed to oversee the project. This meant that the government had to purchase the land from different owners.

“The state government had sanctioned Rs 18 crore to acquire land for this campus, but the negotiation took a long time to settle,” he added. It was only in 2018 that the land needed for the medical institute was handed over to the government.

The timeline got further stretched as political instability between 2015-17 impeded progress.

“Every few months, there was a change in the government, so making important decisions took time,” Longkumer explained.

When the Kohima medical college was approved in February 2014, Neiphiu Rio of the Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party (NDPP) was in his second term as Chief Minister. A few months later, in May 2014, TR Zeliang of the Naga People’s Front (NPF) assumed office. Within three years, in February 2017, he was replaced as CM by his NPF colleague Shurhozelie Liezietsu. But four months on, Zeliang was back as CM, serving for eight months before Rio returned to power. Rio is now the incumbent CM with Zeliang as his deputy.

In February 2021, Rio announced plans in the state assembly to get the college started from 2022-2023 but failed to deliver. In August of the following year, the Nagaland government assured the Kohima Bench of the Gauhati High Court that it aimed to admit the first batch for the academic year 2023-24.

But once construction started, geological conditions created a new set of challenges. Land instability caused by building activities led to landslides, necessitating the intervention of geological engineers to ensure that the site was safe for structures to stand.

“This part of Nagaland is a sinking zone, the mountains cannot bear the weight,” said NIMSR’s dean Bhattacharya.

Vellore, because of the Christian Medical College (CMC), has become a city. The location is not very important

Dr Kika Longkumer, state health and family welfare department

Insurgent groups are yet another impediment. According to the police, these groups, in an attempt to exert control, stall work at every level. Even the simple process of trucks entering Nagaland is problematic. “Drivers have to pay an ‘unofficial’ toll to several insurgent groups — a rough estimate of Rs 60,000 per truck,” said a senior police official.

With the Covid pandemic adding another layer of complexity, it was only in 2022 that construction started in full swing.

Commuting to the main town, which is nearly 6 km away, is expensive and students only leave the campus when it’s essential. There are no buses and private taxis charge around Rs 300 for a one-way journey.

Vellore hopes, regional realities

Now that at least one building is up and running, Nagaland’s health and family welfare department is optimistic. The government sees NIMSR as the path to elevating the standard of healthcare services, enhancing manpower production, and addressing the doctor-population ratio in the state.

Longkumer envisions Kohima district’s Phriebagei evolving into Nagaland’s equivalent to Vellore in Tamil Nadu—a thriving hub anchored by a medical college.

“A medical college is a big establishment, it’s sort of an industry,” Longkumer said. “Vellore, because of the Christian Medical College (CMC), has become a city. The location is not very important.”

Longkumar was optimistic about private entrepreneurs setting up transport and other services in the area, solving accessibility problems, and generating employment.

Within the campus, however, senior faculty members—most from outside the state—are coming to terms with the way things proceed in the hill state. They often murmur about the slow tempo and pace of life and the challenges of navigating insider-outsider dynamics in a tribal society.

During the inauguration on 14 October with Union Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya in attendance, one of the faculty members from another state had worn a sari. It’s what she always wore for formal functions, but here in Kohima, Naga staff kept asking her why she was wearing a sari and not a kurti or any other attire.

Many out-of-state professors are still struggling with the names of the students. Sekyumong, an 18 year old from Kiphire district, gave himself the nickname ‘Raju’ to make it convenient for them.

“My roommate’s nickname is Rahul,” he said with a grin.

The medical institute, for all its promise and potential, has not begun with a bang. It has yet to generate a buzz among residents the way AIIMS-Jodhpur did.

New dreams unleashed

At the anatomy department’s dissection hall, a group of around 33 students gather in front of a suspended human skeleton. Twenty-one-year-old Yangam Konyak pays close attention as the professor discusses organ systems.

Her hometown is in Mon, one of Nagaland’s most backward districts. Yangam is the fifth child among her six siblings, and the first one from her village to pursue medicine.

“I had no role models, and prepared for the NEET on my own. And I couldn’t clear the exam twice but I finally got a seat this year. I said to myself, one last try, before I give up on this dream,” Yangam said.

Though she got placements at two central universities, she chose the state-run NIMSR because it was closer home. “It takes me 10 hours by bus to visit my parents,” she said.

Her father, a government school teacher, and mother never put any kind of pressure on her. Now that she’s on the path to becoming a doctor, she wants to specialise in gynaecology.

With no WiFi, life on campus can be isolating and demanding. Weekdays go by with classes from 9 to 4 pm. “On weekends, we do our laundry,” Yangam jokes.

For Sekyumong who wants to specialise in neurology, NIMSR is his chance to become a doctor and make his mother happy. As a nurse, she wanted one of her three children to be called ‘Dr’.

“My mother told me that if I become an engineer, I would end up working in a garage or as a teacher or a farmer,” said Sekyumong, whose two elder sisters are studying pharmacy and physiotherapy, respectively.

Commuting to the main town, which is nearly 6 km away, is expensive and students only leave the campus when it’s essential. There are no buses and private taxis charge around Rs 300 for a one-way journey.

But students have devised their own time forms of recreation. They organise Sunday gatherings in the dining hall where they conduct prayers, share stories, and perform or play music.

The attitude of the Naga students has touched the hearts of the teachers.

“I have taught in other states as well and I see a difference. The students here are obedient and sincere. They are self-dependent. And I believe sincerity matters more. Intelligence has nothing to do with medical science,” said Dr Arun Sharma from Assam who teaches in the anatomy department.

Students are proud to be the first batch of cohorts from Nagaland’s first medical institute. They wear it like a badge of honour and hope that it will get them good jobs when they graduate five years down the line.

“We are the first batch of this college, so I am hoping our chances of getting a job will be higher,” said Yangam. But they also feel the absence of seniors to guide them. “We have to buy all our books instead of receiving hand-me-downs,” she added.

However, Amal Jacob from Kerala, one of the 15 students from other states, called the absence of seniors a “good thing”.

Jacob said that he did not find it difficult to adjust to life in Nagaland, especially since everyone speaks English.

“The public transport isn’t developed here and the roads might be bad, but people here behave better when stuck in traffic than back home,” he pointed out

Ritu Thurr, principal director for health and family welfare, anticipates that the young doctors from NIMSR will enhance tertiary-level care within the state, eliminating the need for patients to seek specialised medical services elsewhere.

A few surprises for out-of-state faculty

The faculty at NIMSR comprises 43 teachers, of which 90 per cent are from Nagaland.

“The junior-most faculty, assistant professors, and senior residents are from Nagaland,” said dean Bhattacharya. She explained that the National Medical Commission (NMC) criteria mandate that a medical college have a teaching hospital. In NIMSR’s case, the Naga Hospital Authority Kohima (NHAK) was integrated to fulfill this role, and its doctors automatically became part of the medical college faculty.

The remaining 10 per cent of the faculty come from various other parts of the country— Delhi-NCR, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Manipur, Assam, and Bihar.

Those who have just moved to the nascent medical college in a new state are adjusting to an unfamiliar reality.

A faculty member with prior experience in medical colleges in Bihar, Punjab, and other states highlighted significant differences in working conditions at NIMSR compared to established institutes.

“For Nagaland, it’s the first medical college, so it takes time to synchronise everything,” the teacher said.

The issues range from inconveniences such as the staff quarters lacking power outlets for washing machines to administrative hiccups like income tax not being deducted from salaries.

“Files don’t move for a long time. We are finding it difficult to progress as fast as we want,” the teacher said. Before the faculty’s arrival, they added, instruments, and chemicals were procured that proved “no use to any department”. The makeshift library awaits a librarian.

But Joshil Kumar from Odisha, who heads the physiology department, said he encountered pleasant surprises as well— such as the welcoming nature of people, which is “quite contrary to what people believe” elsewhere. “Hospitality here is next level,” he added.

The institute’s functioning is slowly beginning to smoothen too. First-year classes and practicals for anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry are on track, and work is underway to set up departments for forensics, community medicine, pathology, microbiology, and pharmacology.

The existing departments, Bhattacharya said, are preparing for inspection by the NMC for the first renewal of the institute’s accreditation.

A Rs 21.19 crore knowledge centre is expected to be ready by March. “It will have four lecture theatres and a central library. It is being constructed with (funding from) the World Bank,” said Bhattacharya.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has also committed to constructing a 14-storey 400-bed hospital exclusively for NIMSR, on the adjacent cliff. The construction is expected to be completed in 2026.

Also Read: Maharashtra’s cluster schools have computers, more teachers. 10,500 schools will be merged

‘Ball has started rolling’— but slowly

A fully operational NIMSR is expected to transform the healthcare landscape of Nagaland.

Ritu Thurr, Nagaland’s principal director for health and family welfare, anticipates that the young doctors from NIMSR will enhance tertiary-level care within the state, eliminating the need for patients to seek specialised medical services in places like Assam or Manipur.

“There are 130 primary health centres and 21 community health centres across the state. We have medical officers, but we have a shortage of clinical specialists,” he said.

In addition to bolstering healthcare capacity, Longkumer anticipates substantial contributions from the medical college to research, particularly in disease spectrum and surveillance.

But the medical institute, for all its promise and potential, has not begun with a bang. It has yet to generate a buzz among residents the way AIIMS-Jodhpur did.

They are hesitant to dream, and sceptical of the way things work in this corner of the country.

“The majority of Nagas don’t even know there is a medical college since it’s new,” one of the students said.

By now, the area around the campus should have been a bustling mini-town with shops, eateries, bookstores, pharmacies, and markets. Instead, there’s a lone shop outside the campus on which students depend for essentials.

Longkumer acknowledges that “entrepreneurial skill” in Nagaland is a little slow, much like the pace of life. The campus, for now, exists in isolation, bereft of any commercial hustle in a place full of youngsters.

The health and family welfare department is also wary of the challenges that come with operating a medical college. Longkumer highlighted investment, management, and operational costs as sources of potential problems.

“A fully functional medical college will require Rs 100 crore a year in terms of salary, drugs, and consumables, other than maintenance of assets. Nagaland is a revenue-deficit state, so this is a challenge,” he said, adding that Arunachal, Manipur, and Mizoram face similar financial constraints.

As evening falls, the hammers and drills fall silent, and students trudge back to their hostel under the darkening sky.

“The college is still in its infancy,” Bhattacharya said. “Check back in four to five years when the first batch has graduated. The ball has started rolling, it will prosper.”

* Name changed upon request to protect privacy