Bhopal: Pawan Singar stood in the middle of the electrical lab in the engineering college, craning his neck to peer into other students’ notebooks. The professor had just dictated ‘Verification of Kirchhoff’s law’. The students were not only confused about the correct spelling of Kirchhoff but also about words like ‘verification’ and ‘eliminate’.

This is the ‘J section’ of Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology (MANIT) in Bhopal—a classroom of 80 students who are taught in Hindi. For Pawan, a Bhil from Madhya Pradesh’s Jhabua, it marks his first step into the Great Indian Engineering Dream.

In 2022, the All-India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) granted permission to 13 government and private colleges in Madhya Pradesh to offer engineering degree and diploma courses in Hindi. The decision aimed at enlarging the pool of students and making engineering less elitist and more accessible. Additionally, Home Minister Amit Shah announced the introduction of MBBS courses in Hindi.

But last year, only 19 students enrolled in MP’s Hindi engineering courses. Sixteen completed their courses, all from a single private institute, while three dropped out, said Mohan Sen, additional director at the Directorate of Technical Education. This year, a total of 89 students enrolled in just four out of the 13 institutes.

It’s a similar story in MANIT, a centrally funded institution of national importance in technical education.

Over the two previous academic sessions, only 27 students out of 334 chose to stick with the Hindi section in MANIT.

If Hindi is the tool to ease a large number of small-town students into engineering, it has also filled them with questions about how far it will take them, whether they will land big city jobs, and if they will always feel inferior to their English-speaking counterparts. What’s worse, the textbooks and learning materials are just not ready in Hindi and regional languages. The Great Indian Engineering Dream is still largely dreamt in English. And creating English-Hindi silos is just not cutting it.

Pawan is the youngest of three siblings. His father works as a supervisor in the district court, while his mother looks after the family at home. He is the first in his family to pursue engineering, a dream he has held close since he was in class 4.

He insists he is no stranger to English; he started studying it in class 11 and took the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) in it. It gives him an edge even now: Hindi section students must write their term papers in English.

But his friends, Mahendra Bishnoi and Parmet Jangid, both from Jodhpur, have completed their entire education in Hindi, including the JEE. Mahendra now struggles to grasp the concepts of theoretical subjects like environment science and chemistry in English.

In their class, associate professor Dr Anoop Arya is mindful of India’s deep language divide. He briefs the students on safety instructions, first in English, and then slowly in Hindi.

Pawan and his friends blank out during class lectures and look up YouTube channels that can help them learn the concepts. They then use Google Translate to make notes from English to Hindi. Finally, they learn them again in English to write their tests.

What weighs on their minds is the upcoming test of environment science in September.

“Job placement is a long way off. Right now, I just hope I don’t fail any courses,” Mahendra said.

However, for many other students, like Pawan, a bigger dilemma looms. The Hindi section, meant to be a bridge over the language barrier, now seems like a wrong turn on the road to high-paying jobs and status.

Also Read: Phase out English intelligently. But prepare Indian languages for the difficult task first

J is for jumping ship

Regret permeates MANIT’s J section, which caters to students with limited English proficiency. Some completed their entire schooling in Hindi, while others took up English late. A few claim they opted for Hindi-medium instruction “by mistake” during the admissions process.

Some lament not studying English earlier, others rue their admission form mistakes, and many say they wish for more English training within the Hindi section.

Parmet draws inspiration from his elder brother who just completed his engineering from NIT Rourkela and landed a job with Microsoft. Their father, a carpenter, took out a loan of over Rs 30 lakh to get them both educated.

“I used to study for 12 hours while preparing for JEE, but my brother studied for 15 hours. He put in those three extra hours daily to learn English. I know full well that there is no other way,” Parmet said.

Even in the J section, students get notes in English, so they try to catch up using Hindi resources online. “We refer to YouTube channels like Dr Gajendra Purohit to supplement our understanding from the class,” Parmet said.

But despite facing practical learning challenges due to the language barrier, most J section students eventually transition to English-medium sections.

It looked bad that we were part of a section which was called the Hindi section

-Gaurav Barwal, MANIT student

This has been the trend ever since MANIT established the section in 2021 in response to the government’s drive for Hindi in the National Education Policy (NEP).

Over the two previous academic sessions, only 27 students out of 334 chose to stick with the Hindi section.

According to Professor MM Malik, the dean of academics at MANIT, the total first-year intake comprises 1,203 students. In 2021, 150 students opted for engineering in Hindi, but by the end of the first year, only 8 remained in the section.

In 2022, out of the 184 who started in the Hindi section, only 18 stayed, with the rest transferring to English-medium sections. In 2023, 81 students signed up for engineering in Hindi. How many will continue is open to question.

For some students, switching sections is a pre-emptive measure. First-year engineering students all study the same subjects, but as they specialise, the infrastructure for Hindi education becomes more fragmented.

Students also say that not starting with English puts them at a long-term disadvantage.

“There is an understanding that Hindi leads to poor placement opportunities as most companies opt for students who are fluent in English. The placement interviews themselves are largely conducted in English,” said Ashish Yadav, a 2022-batch J section student who made the switch.

For others, being in J section wounds their pride.

“It looked bad that we were part of a section which was called the Hindi section,” said Gaurav Barwal, who asked to be shifted to an English-medium section last year.

Hindi-medium baggage

Pawan thrives in the college routine, kickstarting his day with yoga and meditation before diving into classes.

Yet, in his third-floor hostel room, there is a slight sense of unease. Pawan is anxious to prove that he is no different from his English-medium roommates, Akash Aggarwal and Vivek Gupta.

As they sit and chat on their single beds, they all insist that Pawan’s place in the Hindi section was the result of a form-filling misadventure.

“I studied in Hindi until class 10, but I gave my class 12 exams in English. I knew it would be difficult to do engineering otherwise. It was a struggle at first as I could not understand what the teachers were saying, but now I know English. I gave my JEE in English,” Pawan said.

He claims he got a place at the Indian Institute of Space Technology in Thiruvananthapuram, but chose MANIT because he wanted to be closer to home. He pointedly peppers his sentences with English words.

Identifying as a Hindi-medium student comes with baggage. It doesn’t help that English fluency is taken as a yardstick for intelligence.

In June, a first-year engineering student in Indore died by suicide, reportedly after being mocked for not understanding English and failing papers.

Even MANIT professors acknowledge that Hindi-section students must work harder to keep up with their batchmates. And that, ironically, they must improve their English skills to avoid future difficulties in their studies and careers.

Resource crunch—for both Hindi & English

The Hindi-medium J section is a good entry point for the large bottom-of-the-pyramid population, but within the first few months, they realise that it is not a good place to grow roots in. They start getting anxious to integrate and soon find study materials and coaching quality is just better in English.

Ashish Yadav left the J section to join his English-medium batchmates last year. It was a pragmatic choice since he had to read notes and write papers in English anyway. More and more Hindi-medium students prefer an easier and gentler English classroom rather than a parallel Hindi classroom.

“I’m still learning English, and there are two more years for placements. But I strongly feel that there is a need for a separate English class for students coming from a Hindi background to equip them for the future,” said Ashish, who comes from Jhansi in Uttar Pradesh and aspires to work as an engineer in a PSU.

Work needs to be done to make textbooks accessible to all in simple Hindi

– Mohan Sen, Directorate of Technical Education

But the larger policy push appears to be to create silos, even though English can never be entirely wished away.

Dr. Karunesh Shukla, director at MANIT, said that the introduction of engineering in Hindi is in line with the NEP and intended to provide an “effortless” learning experience.

“We have taken several measures such as issuing laboratory manuals in both English and Hindi, and allowing students to choose Hindi as their medium for vivas. We do not force any students to choose any particular language, it is entirely up to them,” he said. “But the final examination paper is written in English only.”

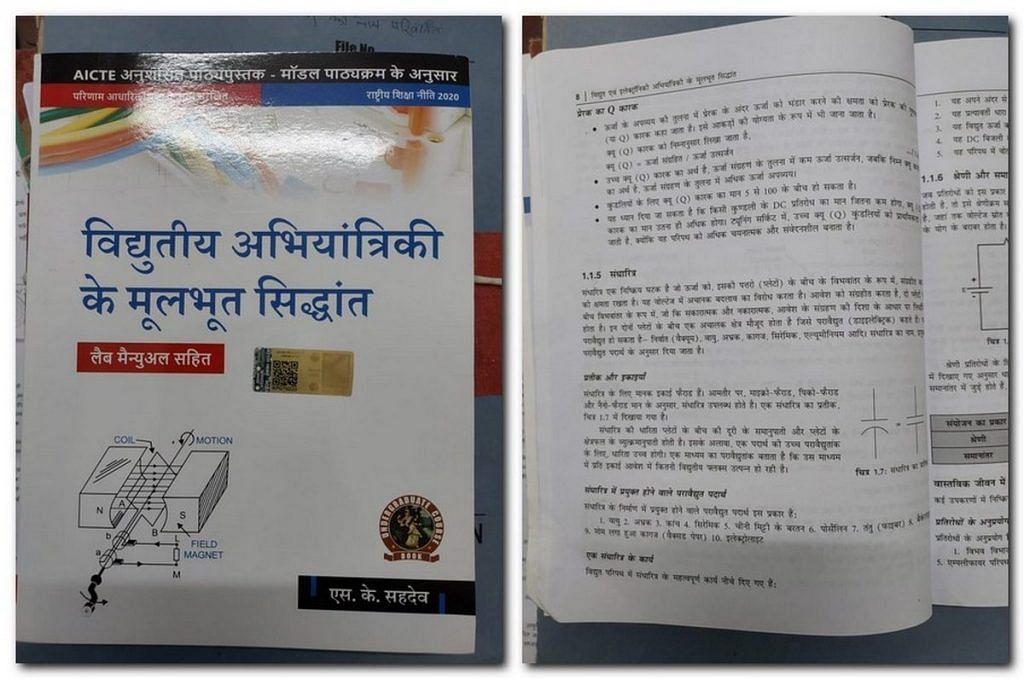

Yet, the availability of Hindi course materials remains limited. Even AICTE-approved textbooks feature dense and intricate language that is difficult for students to comprehend.

“Work needs to be done to make textbooks accessible to all in simple Hindi,” Sen said.

Twenty books have been translated for first-year students so far and another 80 are in the pipeline for the second year, said Shashirangan Akela, the nodal coordinator for translation of engineering books in Hindi.

The AICTE has now also appointed authors to write engineering books that will be translated into simple Hindi and then reviewed by expert committees.

Low demand & question of ‘exploitation’

The lukewarm response to Hindi engineering extends beyond MANIT. The 13 state institutes in MP that introduced Hindi engineering programmes last year also grapple with low enrollments — and also of students moving out of Hindi midway.

All the 19 students who enrolled in 2022 were from private universities in Indore. The highest number of admissions — 16 — were in the Acropolis Institute of Technology and Research, which offers a computer science course in Hindi. This was followed by two admissions for computer science in IPS Academy (Institute of Engineering & Science) and one in the Hindi biomedical engineering programme at the GS Institute of Technology & Science.

Engineering in India isn’t just a field of study, but a ticket for social mobility. The unwritten rule is that none of it is possible without English.

Of the 19, only the 16 students from Acropolis completed a full year.

PC Sharma, the institute’s director, said students used a mix of languages in their coursework — writing in Hindi and technical work in English.

He added that computer science is a field where technical proficiency matters more than language comprehension and writing.

“Students are tested for their technical skills. Even during placements, many companies conduct entrance exams to ensure students have the required skills to develop the programmes they need,” he said.

The sole student who took admission at GS Institute of Technology wrote his answer paper in English, and is repeating his first year.

This year, 89 students have enrolled for Hindi engineering across MP. Acropolis Institute and GS Institute saw higher intakes of 74 and nine respectively. IPS Academy and Dadaji Institute of Technology & Science in Khandwa enrolled four and two students respectively.

But there is a sliver of doubt about whether increased enrollments signify an increase of interest in Hindi or something more cynical.

Seats reserved for engineering in Hindi should not be exploited by English-medium students

-Prof Prashant Bansod, GS Institute of Technology & Science

Initially, in August, 17 students had enrolled to pursue biomedical engineering in Hindi at GS Institute. However, by September, after successive rounds of counselling, this number had decreased to nine, with the other eight students moving to other branches of engineering that are taught in English.

This sparked worries that some students might be applying for Hindi seats merely to boost their chances of admission, knowing they could choose to write papers in English or switch to a different section later.

Professor Prashant Bansod, head of department of biomedical engineering at the GS Institute of Technology & Science, told ThePrint that not all of the initial enrolments this year had a Hindi-medium background.

“Seats reserved for engineering in Hindi should not be exploited by English-medium students,” he said.

“In this situation, we are trying to ascertain if students should be allowed to choose their language for examination, or if Hindi should be made mandatory,” he added.

But the most pressing challenge of all is drawing more students to Hindi engineering courses.

Even Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya (RGPV), a technical university with a large percentage of students from rural MP, had no takers for Hindi engineering.

RGPV, notably, is the state’s nodal institute for technical education, tasked with conducting examinations, deciding policies, and governing both private and government technical institutes across Madhya Pradesh.

The AICTE had given the go-ahead for the university to offer civil, mechanical, electrical, computer science, electronics, and telecommunication engineering courses in Hindi, but none of these programmes got off the ground, said Professor S.S. Bhadoria, head of department.

“During orientation we ask students if they want their medium of instruction to be in Hindi, but we have had no takers for it,” he added. “A survey carried out last year also found little enthusiasm for engineering in Hindi.”

However, Rakesh Khare, dean of admissions as GS Institute of Technology & Science, said he was hopeful that engineering in Hindi would become more popular over time.

“Any policy will take a few years before being successfully implemented on the ground,” he said.

Also Read: MBBS books in Hindi add more problems to the syllabus. Amit Shah, BJP didn’t think though

A hunt for solutions

Engineering in India isn’t just a field of study, but a ticket for social mobility. The unwritten rule is that none of it is possible without English. Sen said this perception needs to change.

“We spoke to students last year and they feel multinational and global companies look for those that are fluent in English, whereas Hindi is seen as a disadvantage when it comes to employability,” he added.

To address this, he suggests that institutes should invite companies like Wipro and TCS to come on campus and boost the morale of students who have opted for engineering in Hindi.

“Even when the NEP was being formulated, industry stakeholders were consulted. A similar exercise needs to be undertaken by universities as well to show students that there are enough takers for those who pursue engineering in Hindi,” Sen said.

But some professors argue that Hindi cannot be treated as a replacement for English.

A faculty member from RGVP said that even if students complete their engineering degrees in Hindi, they will miss out on the wealth of research published in international journals, which are mostly in English.

“We live in a globalised world,” he said. “Knowing English is beneficial.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)