Mumbai: Six-year-old Dhairya Chauhan is very fond of Aai, the Marathi word for mother. He follows her wherever she goes, enjoys sharing his day with her and laps up the delectable dishes she whips up for him. But she is not Dhairya’s mother. She is his neighbour, Anita Mote.

The Marathi-speaking Motes and Gujarati-speaking Chauhans have lived next to each other in an apartment building in Mumbai’s western suburb of Andheri for more than two decades and have almost become an extension of each other’s families.

“We share a close bond. We celebrate each other’s festivals, exchange plates of food if there is something special that has been cooked at home. Dhairya is here every day,” 57-year-old Mote says.

While this particular Gujarati family is “a very nice one,” Mote cannot say the same about all Gujaratis in Mumbai.

“If they are nice to us, we will be nice to them. If they don’t give us respect, we will not let it pass,” says Mote, who has lived in Mumbai all her life.

This sums up the Gujarati-Marathi equation in Mumbai, a city that has been a home to both. They live next to each other, celebrate each other’s festivals and have formed close friendships. But at a macro, intangible level, there is an undercurrent of unease that runs between the two communities, fuelled by history and politics. And every time there is a new incident of conflict, the wound turns raw again. Politicians rub salt on it and keep it throbbing for a while.

Last week, a Marathi woman, Trupti Deorukhkar accused a Gujarati father and son—Praveen and Nilesh Tanna—of denying her an office space in Mulund’s Shiv Sadan society because she was a Marathi. She filed an FIR against the father-son duo and recorded a video on social media, saying she was “shocked and saddened at what was happening to a Marathi person in Mumbai.”

The incident drew sharp criticism from politicians across parties in Maharashtra. Leaders of the Raj Thackeray-led Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), which grew on the ‘sons of the soil’ agenda in Mumbai, landed up at the Mulund housing society and made the Tannas apologise.

Shruti Tambe, head of the sociology department at the Savitribai Phule Pune University, says the roots of the Marathi versus Gujarati debate lie in the capital versus labour contradiction. Now, it has become more of a political ballgame now.

Before independence, the capital in Mumbai was owned by different kinds of people – the Parsis, Jews, Anglo Indians, Marwaris, Jains, Pathare Prabhus and the Sonars.

“Then post-Independence, the capitalist class became increasingly monocultural with the Gujarati- Baniya combine. Then ownership and investment was dominated by this very powerful capitalist lobby, slowly turning the capital into a monopoly. The labour, meanwhile, though multicultural, was predominantly from the Maharashtrian hinterland,” Tambe says.

But limiting the conflict to a Marathi-Gujarati prism is not enough, as they are not homogenous communities.

“What is happening to Marathi Dalits, Gujarati Dalits, Marathi Muslims, Gujarati Muslims, tribals from the two communities? The real problem is that if you lose pluralism due to prejudice, the fabric of the society breaks,” she adds.

Also read: ‘No flats for Marathis:’ FIR against Gujarati father-son in Mumbai after woman alleges bias

Whose Mumbai is it anyway?

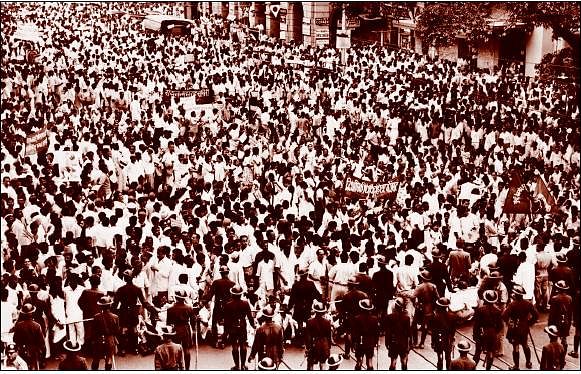

In the late 1950s and 1960s, around the time of the Samyukta Maharashtra movement, Mumbai, then Bombay, was besieged by slogans such as ‘Mumbai amchi, nahi konacha baapachi,’ and ‘Mumbai Tumchi, Bhaandi Ghasa Amchi.’

The first slogan, proclaimed by the Marathi population, meant, ‘Mumbai is ours and does not belong to anyone’s father.’ The second one was a retort, reportedly coined by the then Chief Minister of Bombay State, Morarji Desai, who was a Gujarati. It meant, ‘Mumbai is yours, now get to scrubbing our utensils.’ Desai is said to have been strongly in favour of a separate city-state of Bombay.

The Samyukta Maharashtra movement was an agitation by Marathi-speaking leaders, mainly from Leftist parties, to press for the creation of a separate state of Maharashtra on linguistic grounds with Bombay as its integral part. The state was formed on 1 May 1960, carved out from the erstwhile Bombay State and it included the city of Bombay.

Mumbai’s Marathi population, especially the generation that lived through the Samyukta Maharashtra movement, likes to recall how the Maharashtrians had to fight tooth and nail and pay with their blood to get the crown jewel of Bombay in their share. The Hutatma Chowk monument in Mumbai’s Fort area, built to commemorate the 107 martyrs of Maharashtra’s movement for statehood, stands testament to this.

The Dhar Commission, appointed by the Union government in 1948, to look into the feasibility of organising states on a linguistic basis, had recommended that Bombay city be constituted as a separate unit.

The Commission had said, “The city of Bombay stands in special relation to Maharashtra, Gujarat, and to India as a whole . . . Industrially and commercially, it is the hub of India’s financial and industrial activity. And altogether it excites some of the deepest emotions in Marathi and Gujarati hearts…”

Later, the States Reorganisation Commission in its 1955 report recommended the formation of a bilingual state of Maharashtrians and Gujaratis comprising large areas of the Bombay State and other regions.

It was the fear of losing entire industry to the Gujaratis—Neera Adarkar, urban researcher

Maharashtrians passionate for a unilingual state with Bombay city staunchly rejected this proposal. It led to the creation of a Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti in 1956 with leaders such as Shreedhar Mahadev Joshi, Shripad Dange, Narayan Gore, Anna Bhau Sathe, Prahlad Atre, and Keshav Thackeray among others at the forefront.

Neera Adarkar, an architect, urban researcher and a Maharashtrian who grew up in Mumbai, says the Samyukta Maharashtra agitation was not as much against Mumbai’s Gujaratis as it was against the government. There were hardly any reports of violence against Gujaratis.

“It was a struggle led by mill workers and union leaders. They feared that if Mumbai went to Gujarat, the entire capital there would be legitimately owned by Gujaratis. It was the fear of losing an entire industry to the Gujaratis,” she says.

Also read: Gujarati archaeologist Bhagvanlal with little English, lot of Sanskrit helped British read edicts

The political economy

The birth of the Bal Thackeray-led Shiv Sena was a gradual consequence of this turmoil. Thackeray’s father, Keshav Sitaram Thackeray, had seen the struggle for Mumbai from close quarters.

When the Shiv Sena was officially launched on 19 June 1966, it was not exclusively anti-Gujarati. But targeting wealthy Gujarati businessmen and South Indians in Mumbai was a large part of its ‘sons of the soil’ agenda.

“There was a lot of gadbad (confusion) in the mahaul (environment) back then,” says 83-year-old Hemraj Shah, who moved to Mumbai 70 years ago and started living in a housing complex of Tardeo in South Mumbai that had a large number of Gujaratis as well as Maharashtrians.

“All of us children—Marathi and Gujarati alike—used to play together. The gadbad was not in our society. It was all outside. Morarji Desai had ordered firing on (Samyukta Maharashtra) protesters. We didn’t understand all the politics back then, but there was tension in the air,” he adds.

Shah, who heads a Gujarati federation in Mumbai, joined the Congress in the 1990s “more for social work than for being in politics”. When Sharad Pawar broke away from the Congress and formed Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) in 1999, Shah followed him. Then in December 2016, he joined the undivided Shiv Sena and has been at the forefront of the party’s outreach efforts for Gujaratis.

“Uddhav Thackeray respects Gujaratis, but if any local Shiv Sena workers cause members of the Gujarati community any trouble, it helps for me to be there as a fellow party worker. I can ask them to calm down,” Shah says, justifying his decision to move to Shiv Sena. Even after the split in the party in 2022, Shah has remained loyal to the Thackerays.

The Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) has itself undergone a massive metamorphosis over the past decade and so has its approach towards Gujaratis, largely due to political compulsions.

Over the years, the percentage of Marathi voters has significantly dropped in Mumbai’s demographics. The size of families living in small modest homes and chawls in the city’s Marathi areas of Dadar, Parel, Lalbaug and Girgaum swelled. As redevelopment policies replaced the creaking buildings and decrepit chawls with swanky high-rises, many of these middle-class Maharashtrian families moved to Mumbai’s peripheral towns such as Thane, Dombivli, Virar, or even cities like Pune and Nashik for bigger, more affordable homes.

The collapse of textile mills in Mumbai’s Marathi heartland, and their replacement with luxury housing towers in the early 2000s further skewed that equation.

The Union government-appointed States Reorganisation Commission said in its report that Maharashtrians, as per the 1951 Census, were a minority in the Bombay city at 43.6 per cent of the population. Today, politicians claim the population has fallen to 28-30 per cent, which is also the ballpark figure for the city’s Gujarati, Marwari and Jain voter base.

After 2006, the newly formed Raj Thackeray-led MNS had also attempted to build its capital from this political economy of Maharashtrians versus outsiders. Last week, when MNS workers coerced the Tannas to apologise for allegedly denying Deorukhkar a house, the party made it a point to emphasise how it was the only one to take action for the cause of Maharashtrians.

The splintering of the alliance of the undivided Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has further muddled this Maharashtrian vs Gujaratis tussle. Within the alliance, the BJP had cultivated its following in Mumbai’s Gujarati-speaking areas, while the undivided Shiv Sena pulled votes from the city’s Marathi bastions. When the partnership of the two parties ended in 2019, both had a political compulsion of strengthening themselves in each other’s domains. The BJP started organising events such as ‘Marathi dandiya,’ while the Thackerays held ‘Jalebi Fafda Sundays.’

With two Gujarati politicians (Narendra Modi and Amit Shah) at the most important positions in the government, there has been a steady rise of Gujarati nationalism even in the streets of Mumbai in certain pockets—Sanjay Patil, researcher at Mumbai University

The Thackerays slammed Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train project, calling it an attempt to separate Mumbai from Maharashtra by bringing it closer to Gujarat. The BJP leader and deputy Chief Minister of Maharashtra Devendra Fadnavis criticised the Thackeray-led party for crying over investment projects going to Gujarat saying “Gujarat is not Pakistan.”

“With two Gujarati politicians (Narendra Modi and Amit Shah) at the most important positions in the government, there has been a steady rise of Gujarati nationalism even in the streets of Mumbai in certain pockets,” says Sanjay Patil, a researcher at Mumbai University’s politics and civics department.

Patil adds that this Gujarati nationalism will be a big challenge for the Shiv Sena (UBT) and MNS.

“There is anyway bitter history over the battle for Mumbai between the two communities, and over the years despite the liberalisation post 1991, Maharashtrians have been unable to establish control over the city’s economy. All of that, combined with the recent politics is likely to make the Gujarati vs Marathi divide a major flashpoint in Mumbai elections,” he says.

The Mumbai civic body, which has been under a state-led administrator’s control since March 2022, is due for elections.

According to Patil, only upper crust Marwari and Gujarati families could afford the luxurious houses built on erstwhile mills. This sowed the seeds of ghettoisation in the city.

Also read: Maratha reservation protest isn’t just about quota. It will end dynasties

Two sides of the same coin

The alleged discrimination against Deorukhkar in Mulund is hardly an isolated incident in the Marathi-Gujarati dynamic.

In 2021, a Marathi-speaking man was reportedly denied a one BHK flat at Mira Road, a township in the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region because the building was exclusively for Gujaratis, Marwaris and Jains.

In 2015, a real estate developer reportedly refused to sell a Marathi-speaking man a house in a residential project in Malad, a western suburb of Mumbai, allegedly because he ate non-vegetarian food. The developer had, however, denied the allegations saying his company was not comfortable dealing with the Marathi complainant because of his approach.

Meat-eating habit of Maharashtrians has often been a bone of contention, especially when it comes to finding a house in areas with Gujarati majority.

Adarkar, who spent her childhood in a Gujarati-dominated neighbourhood near Gowalia Tank in South Mumbai, recalls how not too long ago, in the chawls of Girgaum, Gujaratis and Maharashtrians would share walls as neighbours.

“There was no question of food intolerance. But gradually, this system ruptured. Gujaratis started leaving the chawls to go into the higher income bracket of housing. This is when food politics started playing out in Mumbai,” she says.

She recalls how there has been a spirited campaign by residents of high-rises in Lalbaug with a significant Gujarati population to get an old fish market to shut down. Lalbaug is among the Marathi heartland areas that have fast metamorphosed into an upscale residential destination.

And yet, last week’s incident of Mulund has left 34-year-old Ajay Wadkar, a media professional who has lived in Mumbai all his life, “shocked.”

Wadkar’s generation, which has no direct memories of the Samyukta Maharashtra agitation and disregards what political parties say, doesn’t believe that there can be such severe differences between Marathis and Gujaratis in Mumbai.

“In my school I had a close friend who was Gujarati. In my college, I had a lot of Gujarati friends and even now I have Gujarati colleagues who I get along with fabulously. There could be a few people who have had bad experiences, but overall, there is no major Marathi-Gujarati divide,” says Wadkar.

He is even willing to give the Tanna father-son duo the benefit of doubt.

“We don’t know the background. They may have had some experiences in the past,” he says.

Some Mumbai-born Gujarati speakers of Wadkar’s generation find that they are more socially awkward in their home state of Gujarat than in Mumbai. The Gujarati and Maharashtrian cultures seem like two sides of the same coin in Mumbai.

Forty-three-year-old Rahul Patel, a script writer for television, films, theatre and web shows, says that 50 per cent of content in Gujarati theatre in Mumbai is adaptation of Marathi plays.

“And they are so relatable for the Gujarati community that many times we can adapt them as they are. Some of our actors are Maharashtrians, about 25 per cent of the workers are Maharashtrian,” Patel says.

He identifies Marathi as his third language after Gujarati and Hindi. He learned the language from his father, a diamond merchant who employed many Marathi workers in his factory.

Meanwhile, back in her cozy apartment in Andheri, as Nandita Chauhan watches her son Dhairya play with Aai—her first interaction with any Marathi family—she thinks about how so many of the stereotypes that she had heard in Goregaon’s Gujarati neighbourhood were perhaps far from truth.

“Maharashtrians are brash. Maharashtrians don’t have a risk appetite.”

“Our neighbours are very nice people. None of these stereotypes apply to them. But, then none of the stereotypes about Gujaratis apply to us either,” Chauhan says.

“Gujaratis are all business-minded. Gujaratis have a lot of black money.”

She just laughs and says, “Forget black. We don’t even have enough of white.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)