Alandi: Just like Delhi’s Yamuna and Bengaluru’s Bellandur lake, a river in western Maharashtra’s Pune district has intermittently started spewing toxic froth. It’s the Indrayani, once praised by saints for its purity.

Today, the river emanates a strong foul odour and the water that splashes on the stone steps to the temple town has turned ugly green. The Indrayani, revered for ages as holy due to its association with spiritual figures in Maharashtra such as Saint Tukaram and Dnyaneshwar, is in danger today, blighted by industrial and domestic sewage. In the past four months, thick acrid foam has twice covered the river near Alandi.

The river flows through several industrial hubs, accruing their pollutants and effluents. But its clean-up suffers from a governance crisis because it falls under the jurisdiction of multiple government bodies who are largely concerned about their own patch and are participants in a blame game, resulting in a piecemeal approach to any attempts at its rejuvenation.

Maharashtra Chief Minister Eknath Shinde’s intervention in December 2023 briefly got all the concerned government agencies on their toes, prompting officials to undertake physical inspections of the sources of pollution. However, devotees of the river wonder whether they can ever have their Indrayani back.

“Indrayani kathi, devachi Alandi, lagali samadhi, Dnyaneshachi”—God’s Alandi rests on the banks of the river where Dnyaneshwar, the saint, meditates, goes a famous Marathi song written by poet GD Madgulkar, composed by PL Deshpande and immortalised in the voice of Bhimsen Joshi. It says, Saint Dnyaneshwar, who wrote the Dnyaneshwari, a critical discourse on the Bhagavad Gita, entombed himself in a ‘samadhi’ at Alandi in 1296. In today’s Alandi, meditating on the banks of the Indrayani would be downright unpleasant and that much more challenging.

Yogi Niranjannath, a functionary of the Santshreshtha Dnyaneshwar Maharaj Sansthan Committee, which looks after the Sant Dnyaneshwar temple in Alandi, says that the Indrayani river is extremely fortunate. Sant Dnyaneshwar was standing on the third step of the riverbank when the river enthusiastically swelled, splashing water on the steps to be able to touch his feet. “It is that river, which has touched his feet and become pure, that we are worshipping. But now all we are left with are these stories and memories,” Niranjannath says.

Just before the river touches Alandi, it passes through a cluster of industrial units in the Kudalwadi-Chikhali area of Pimpri Chinchwad, which, according to municipal corporation officials, are the major cause of industrial pollution in the river and the reason behind the occasional toxic foam. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB), however, maintains that while industrial pollution cannot be overlooked, the river’s fate has become what it is mainly due to untreated, unfettered domestic sewage.

What has happened here is that we have worshipped our river so much over the years, that it is now a major question what we are exactly worshipping, says Niranjannath.

Believers still worship the Indrayani, refusing to enter the temple premises before dipping their feet in the river’s now brackish water, or even bathing in it and having a sip as theertha (holy water).

“If you go to London, the Thames river is neither revered nor worshipped, but the water is totally clean. They don’t worship it, but they keep it clean being the absolute essential part of nature. What has happened here is that we have worshipped our river so much over the years, that it is now a major question what we are exactly worshipping,” Niranjannath says.

Also read: Assam’s Pobitora sanctuary slipped through cracks for 25 yrs. Now it’s rhino vs villagers

A frothing Indrayani

Sambhaji Gawli stands on the stone steps of the Indrayani riverbank in the temple town of Alandi, blessing visitors every now and then, and reminiscing the days when devotees approached the river without flinching.

Gawli, dressed in a conical headgear with peacock feathers, a pristine white attire with a waistband and a Rudraksha necklace, and cymbals in hand, has been a ‘Vasudev’ in Alandi for as long as he can remember. The ‘Vasudevs’ are worshippers of Lord Krishna who typically travel from village to village singing devotional songs, doing ‘uddhaar’ (helping people) and collecting alms.

“Over 30 years ago, there were barely any infrastructural facilities—proper steps to the river bank, benches to sit, toilets. Yet, the Indrayani would be rife, pure. Everyone who would come to the temple would drink the water, have a bath, purify themselves and then go to the temple to take darshan. Now, you have all the facilities here to access the river, but the river itself is so dirty one doesn’t even feel like looking at it,” he says.

The Indrayani river, a non-perennial water body, originates at Kurvande near Lonavala and flows for 96 kilometres through towns such as Kamshet, Induri, Talegaon Dabhade, Chakan, Dehu, Talawade and Alandi to finally meet the river Bhima at Tulapur.

As per MPCB’s standards, if the Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) of a water body is higher than 3 mg per litre, then it is classified as polluted.

BOD refers to the amount of oxygen required for bacteria and other microorganisms to decompose organic matter under aerobic conditions. As per MPCB data for three stretches of the Indrayani river, the average BOD in 2022 was 7.23, 7.1 and 7.4 mg per litre. In 2023, this figure was 5.64, 6.02 and 5.03 mg per litre. MPCB officials attribute the drop to more water being released from dams into the river, resulting in self-purification.

In January of 2024, the river’s BOD surged to 9.5, 10 and 9 for the three stretches. This was also the month when the Indrayani frothed for the second time in two months.

By the end of November last year, an angry Indrayani had started foaming just before Alandi’s biggest spiritual event of the year—the Kartiki Ekadashi, when lakhs of Warkaris congregate in Alandi to mark the period when Saint Dnyaneshwar entered life-long samadhi.

People from the Warkari sect claim to be apolitical and caste-less. They say they trace their roots to the ‘Bhakti tradition,’ which endorses the desire to have a direct relationship with God and rejects rules and ritualism imposed by society. The Warkaris are devotees of Marathi saints such as Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram and Namdeo, among others.

The river’s frothing just ahead of the Kartiki Ekadashi propelled it to be noticed by the political class. CM Shinde intervened, and the issue was also discussed in the winter session of the state legislature in Nagpur in December last year.

Hailing the Indrayani as the “Ganga of western Maharashtra,” Bhosari MLA Mahesh Landge pointed out many unauthorised constructions along drains that the Indrayani directly embraces and asked the state government’s intervention in clearing illegal scrap vendors and industrial units along the river’s bank.

The second issue that he raised was particularly pertinent. He asked the state government to get three authorities—the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation, the Alandi Municipal Corporation and the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority—together on one platform, either by way of joint meetings or through a combined team of all three agencies, to jointly tackle the pollution not just in the Indrayani, but also in the Pawana river, another tributary of Bhima river.

Minister of Industries of Maharashtra Uday Samant said the state government is “very serious” about the issue and plans to get not just the urban planning agencies involved, but also the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) to act on it.

“The coordination between different agencies has increased in the recent months post the CM’s intervention. State Industries Minister Uday Samant has also initiated the coordination from the MIDC. We are conducting a joint survey to try and see if we can create a Common Effluent Treatment Plant for all industrial areas. There are genuine complexities when there are multiple agencies involved, but there is also a genuine realisation at all levels,” says Shekhar Singh, municipal commissioner at the Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC).

About 20 kilometres of the Indrayani falls under the jurisdiction of the PCMC. MPCB officials say it is the most thickly populated stretch of the river, and as a result, the reason for a large portion of the domestic effluents that find their way to the river.

Multiple agencies

There are conflicting theories by different agencies on exactly what is causing the Indrayani to foam. PCMC officials point to untreated industrial chemical waste from neighbouring industrial estates of Chakan, Dehu and Talegaon, among others, while MPCB officials cite the reason to be untreated domestic waste.

“We are not trying to engage in a blame game. We all have our pits to cover, whether it is from the industrial effluent point of view, or domestic waste. But, domestic effluent is a daily occurrence. If that’s the cause, the foaming should not be intermittent,” PCMC Commissioner Singh says.

A senior MPCB official who does not wish to be named says the pollution board spent the past four months researching the causes of frothing and can conclusively say it is due to domestic waste.

“It is all untreated domestic waste, people bathing and washing in the river using detergents and so on. When domestic waste is left untreated and anaerobic conditions are created, it leads to the generation of volatile fatty acids, which generate foam,” an MPCB official says, adding that most industrial areas are not right at the river bank so are not major contributors to the river’s pollution.

Admittedly, the condition of the Indrayani is not as bad as some other rivers that have made national headlines for toxic froth. For instance, the BOD levels of the Yamuna have been about 40-50 mg/litre. Closer to home, the condition of some other tributaries of the Bhima river, such as the Pawana, is in fact, considerably worse than the Indrayani. As per MPCB data, a majority of the stretches of the Pawana river monitored for the water quality had a BOD ranging from 26 to 36 mg/litre.

In January this year, when the Indrayani fumed and foamed, so did stretches of the Pawana. However, the cultural and religious significance of the Indrayani earned it instant attention.

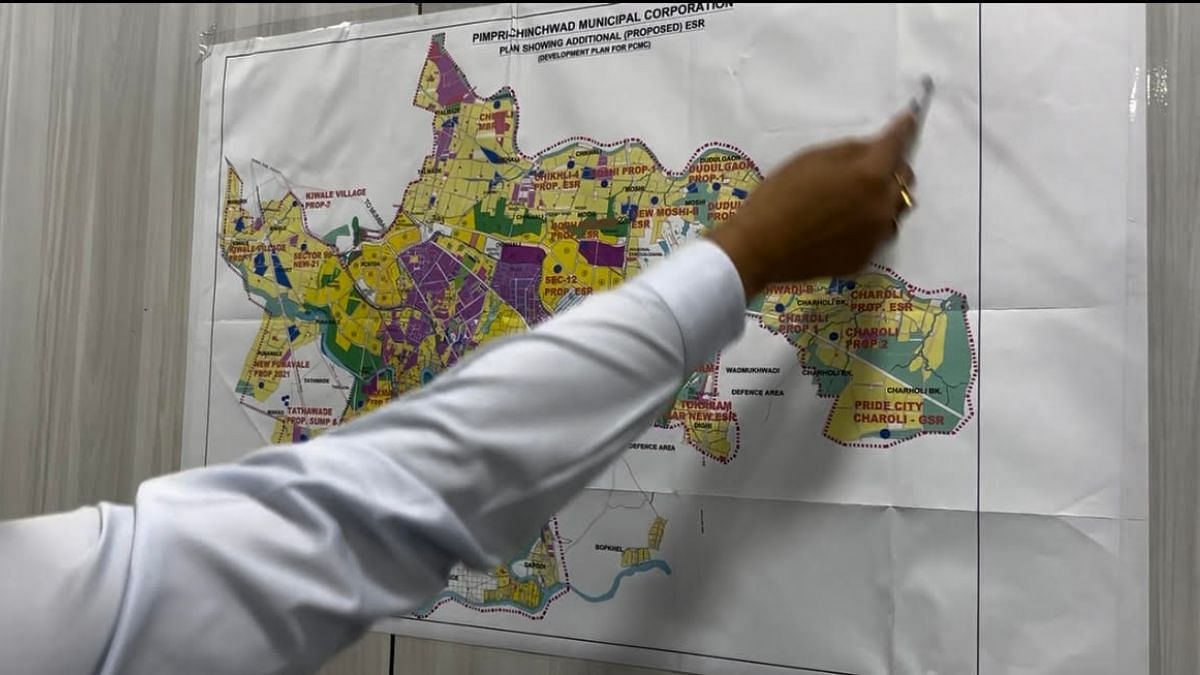

Sanjay Kulkarni, joint city engineer at PCMC’s environment department, stands in front of a large map of the corporation’s jurisdiction in his cabin, pointing to the flow of the Indrayani on its edge. With a pen in his hand, he traces a short stretch of the river that comes under the PCMC’s jurisdiction. He then stretches his hand to trace a considerably longer section.

“All of this comes under the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA), and on the other side is the Chakan industrial area, which isn’t too far from the bank. There are a few drains that meet the Indrayani in our jurisdiction, but there are many more drains along the bank under PMRDA. So there are that many more entry points for pollutants,” Kulkarni says.

The PMRDA oversees the planning for several small towns and villages in the urban agglomeration of the Pune city.

Kulkarni says the PCMC has been in the process of laying down an interceptor line along the Indrayani riverbank under its jurisdiction to ensure untreated sewage that would otherwise enter the river through its multiple drains is trapped and directed to the nearest treatment plant. It has installed mechanical screens on five major drains to prevent effluents, plastic, and other waste from mixing with the river. The corporation is also setting up more sewage treatment plants and has on a pilot basis started an effluent treatment plant in the Kudalwadi-Chikhali industrial area in February this year.

As per letters and presentations that the PCMC has shared with the state government over the past year, the civic area generates about 93 megalitres per day (MLD) of sewage in the Indrayani river basin of which 70 MLD is treated in the four sewage treatment plants in the basin, while 23 MLD is left untreated. The presentations talk about the construction of five more sewage treatment plants, which will add another 31 MLD capacity. The work on the same is in progress.

One of the letters talks about how more than 11 drains meet the Indrayani river from the jurisdiction of the PMRDA, which is undergoing large-scale urbanisation and industrialisation. It also talks about how the river flows through several small municipal councils such as Lonavala, Talegaon, Vadgaon, Dehu, and Alandi that have no sewage treatment mechanisms.

“It is the responsibility of the PMRDA and the MPCB to supervise these municipal councils,” the letter says.

The PMRDA, on its part, has drafted a comprehensive Indrayani rejuvenation plan, covering 82 kilometres of the river at a cost of Rs 540 crore, a PMRDA official says. The plan involves building 23 sewage treatment plants in different villages under the PMRDA’s jurisdiction. PMRDA Commissioner Rahul Mahiwal did not respond to ThePrint’s calls and text messages. This article will be updated when he responds.

Also read: Kerala student politics has even faculty scared. Violence reigns from Maharaja’s to KVASU

“Illegal industries”

At Kudalwadi, a neighbourhood under the Pimpri Chinchwad civic body, a dirty drain gushes in full spate to eventually pass on all its belongings to the quieter, slower Indrayani. The putrid green water flows languidly, with blotches of a black oily residue amid some sparse hyacinth. Bordering the bank is an unsightly mountain of blue and white aluminium and tarpaulin structures.

On one side of the mountain, women armed with masks and brooms are trying to sweep garbage of all kinds into an accumulated heap, which a JCB machine is busy collecting to dispose of. The amount of trash still waiting to be touched makes the effort seem like a lost cause.

“This is a daily occurrence,” their supervisor, who did not wish to be named, says. “By tomorrow morning, this heap of plastic, cardboard, thermocol and styrofoam, among many other things, will be back here for us to clear,” he adds.

The region falls under the administrative jurisdiction of the PCMC and is considered to be among the major sources of pollution for the Indrayani river.

Beyond the cardboards, styrofoam and plastic is a short, uphill, stumbly path, seemingly created by accumulated trash that has been flattened by muck over the years to resemble an entryway. It leads to the inside of the white and blue aluminium and tarpaulin mount, which is a cluster of about 4,000 industrial and scrap units that both PCMC and MPCB claim are illegal.

However, even then, there is a tug of war over who is really to blame for not cracking down on these “illegal industries.”

“After the Indrayani frothed, we served notices to eight or nine units, which we found were discharging effluents. There was a scrap vendor who used to crush plastic and then wash it. Then there was an electroplating unit that we shut down. Since there is no trace of the owners in most cases, we don’t know who to serve the notices to,” an MPCB official says.

There is a shroud of silence inside the units. Workers are unwilling to talk about their employers, partially out of fear, partially out of ignorance. There are no telltale signs of the name of the company or the type of industry. Officials say, only about 300 of the 4,000-odd units here would have the MPCB’s consent to operate, and there is no monitoring of how they dispose of their effluents.

Inside the state assembly in December, Samant promised to send immediate directions to the PCMC to take action against illegal units here.

The MPCB also shot off a letter to the PCMC asking the municipal corporation to conduct a door-to-door search to find out what activities are carried out in the sheds in the region and take action against them. Separately, it has also asked IIT-Bombay to study the entire ecosystem at Kudalwadi-Chikhali and make suggestions to the MPCB on how to improve the situation.

Appasaheb Shinde, president of the Pimpri Chinchwad Chamber of Industries, Commerce and Agriculture, says he doesn’t deny that the Indrayani has to bear the brunt of industrial waste coming out of the PCMC industrial areas. However, he maintains that the corporation is responsible for it.

“The civic body draws 60 per cent of its revenue from taxes from industries, but provides little in return in terms of infrastructural amenities. It is the corporation’s responsibility to set up sewerage tanks, sufficient STPs, and effluent treatment plants. Big companies can try and deposit their waste to the nearest outlet of the civic body, but small industries cannot afford it,” Shinde said. His association has about 100 small and medium industries as its members.

Indra’s Indrayani

Dnyaneshwar Veer remembers his childhood in the temple town about four decades ago. A short break from playtime meant running to the Indrayani, cupping his hands and quenching his thirst before joining his friends again. The memory that stands out the most for him is from parched summers when the waters from the Indrayani would recede.

“We would then dig through the sand on the river bank to hit water, and then drink it. It was that pure,” Veer says. Being a key member of the temple committee now, he is well aware of how rapid urbanisation and industrialisation around Alandi has marred the Indrayani of his memories.

The Alandi town used to even draw water from the Indrayani for drinking purposes. Now, with Indrayani’s water unfit for drinking, the temple town, which has a population of 28,645, gets its water from the Bhama Askhed dam built by the Pune Municipal Corporation.

Niranjannath scoffs at this sorry fact. “It is almost like one Mr. Deshpande has a refrigerator in his house, but still has to knock at the neighbour’s door for some ice,” he says.

As folklore goes, the Indrayani got its name from Lord Indra, Niranjannath and Veer say. Lord Indra sat for his tapascharya at Indori village near Talegaon in the Pune district. The Indrayani, which originates near Lonavala, was influenced by water from Indra’s kamandala (an oblong water pot that sages would carry.)

“If you come to Alandi at 4 am, when everything is pitch dark and the only signs of life are the lights of the temple premises and the reverberation of the sounds of the pakhavaj (a two-headed drum) from the temple, for a moment, the river still feels like Indra’s Indrayani, Bhagwan Dnyaneshwar Maharaj’s Indrayani,” Niranjannath says.

Then, daylight breaks, and reality seeps in.

(Edited Ratan Priya)