Raja Mayong: For several days now, rumours of losing their homes have haunted villagers living near Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary in Assam’s Morigaon district. Under a bhelkor tree, three friends—Parimal Sarkar, Gayanath Biswas, and Lal Mohan Choudhury—gather for a late afternoon adda. Mercifully, it has just rained, but they waste no time discussing the weather. The villagers are caught in a bigger storm—a tussle between the Assam government and the Supreme Court over the sanctuary’s status.

Earlier this month, the Assam cabinet decided to withdraw a 26-year-old forest department notification declaring Pobitora a wildlife sanctuary. But days later, on 13 March, the Supreme Court blocked this move. While wildlife conservationists see the court’s move as a win for the sanctuary, home to the world’s highest density of one-horned rhinos, the villagers fear losing the land where they have been living and farming for years. Anxiety now pervades the daily gossip sessions in the villages surrounding the sanctuary, falling under the Mayong revenue circle.

“We have small portions of cultivable land, and we live by farming,” said 60-year-old Biswas, a resident of Murkata-II, one of the affected villages. “We don’t know what the government or the forest department intends to do, but people have been living here for many years. If Pobitora fully emerges as a reserve, we will have nowhere to go.”

Pobitora has become the latest battleground in the conflict of interests between wildlife conservation and land rights across India. It’s a slender thread, with the tug-of-war often featuring government notifications, court rulings, and forest-dwellers who claim they have been left out in the cold — from adivasis in Melghat Tiger Sanctuary in Maharashtra, to Van Gujjars in Rajaji National Park in Uttarakhand, to tribal villages in Tamil Nadu’s freshly notified Thanthai-Periyar Sanctuary. But Pobitora’s story is different. Here, decades of apathy followed by sudden action have resulted in widespread confusion.

In this case, the Supreme Court ruling pits three parties against each other: the state cabinet, the forest department, and people living on khas land—government-owned fallow land or uncultivated propertywhere no one has established permanent rights. Then, of course there is the silent stakeholder, the one-horned rhino, which is listed as ‘vulnerable’ in the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

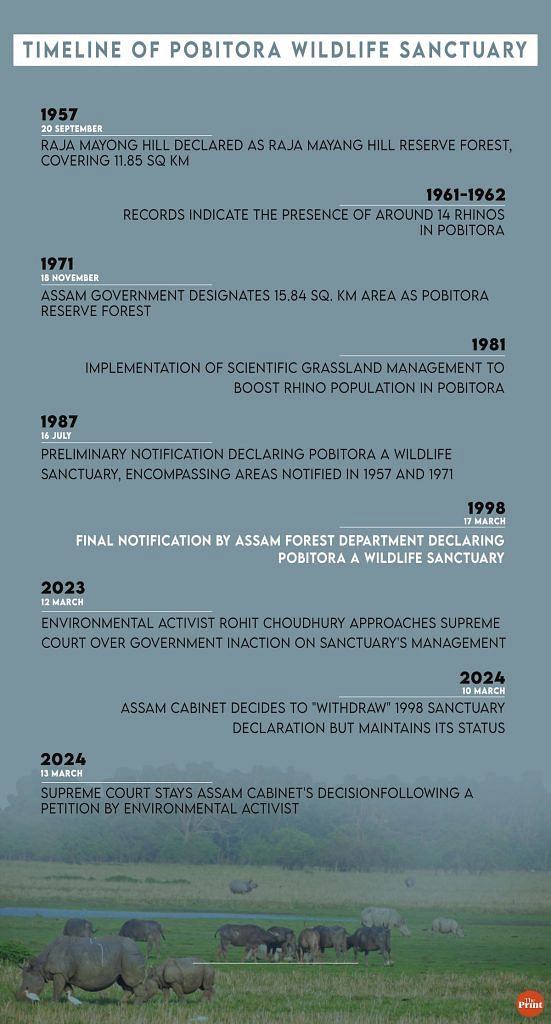

The current situation stems from two key factors: a 1998 notification by the Assam forest department declaring Pobitora a wildlife sanctuary, and subsequent decades of inaction in demarcating its boundaries. But this did not go unnoticed.

In March 2023, a wildlife conservationist petitioned the Supreme Court on the Assam government’s failure to implement the 1998 notification regarding the sanctuary. It was while hearing this case that the court blocked the government’s decision to withdraw the 26-year-old notification.

Now, the district administration is scrambling to comply with the Supreme Court’s directions. Devashish Sharma, deputy commissioner of Morigaon district, said the matter is being “taken up very seriously” and that the land would be handed over to the forest authorities after making a submission before the court.

The purpose is to save the rhinos of Pobitora, and one way of doing so is maintaining good relations with the villagers

-Bibhab Talukdar, chair of Asian Rhino Specialist Group.

He also underscored that the administration intends to identify and protect the constitutional rights of people who own land under a miyadi patta, a government deed that allows the use of land for a certain period. “The history of Pabitora is beyond 1998. There was a time when the people of Mayong used to look after the forest,” Sharma said.

But not everyone who lives here is on tenterhooks after the Supreme Court ruling. Sandhya Biswas, 50, a resident of Murkata-I announced that she had nothing to fear from the authorities because she is availing various government schemes.

“I have ration, widow’s pension, and every other scheme,” she said. “Why will they do me any wrong? I am here to stay.”

Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary is home to 107 one-horned rhinos as of the last count in March 2022. But any more may be too much.

Also Read: Pobitora, a wildlife sanctuary still — SC stays Assam’s withdrawal of 1998 notification

End of a 26-year-old status quo

The rain finally came after weeks of dryness, to the relief of both people and animals. The dry beels temporarily filled with water and a rhino happily wallowed in the wet marshes.

Located about 48 kilometres from Guwahati on the southern bank of the Brahmaputra, Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary is home to 107 one-horned rhinos as of the last count in March 2022. But any more may be too much. A forest official pointed out that the peak capacity has been nearly reached for the sanctuary’s limited rhino-bearing area.

Spanning just 38.83 square kilometres, Pobitora is surrounded by 33 revenue villages, some sharing a boundary with the sanctuary. “Pobitora is much like a courtyard enclosed on all four sides by houses,” pointed out retired forest officer Bhupen Talukdar, with over four decades of experience in the Assam Forest Department. “The wilderness is gone, and the rural ambience too. It has almost become a small town now.”

This explosion in human settlements has brought with it escalating human-animal conflict. On one hand, rhinos and wild buffaloes have been known to damage crops. On the other, the animal habitat has long been threatened by cattle grazing and human interference, with some people still attempting to fish in protected waters. Compounding such issues, floods have led to a shortage of grass and other fodder for the rhinos, while siltation and climate change have resulted in the gradual drying up of swampy areas and water bodies like Tamulidova and Solmari.

The comforting news— no poaching incidents have been reported in Pobitora for the past eight years. Forest officials attribute this success to “greater coordination with the police, improved intelligence systems, and patrolling mechanisms”.

Now, the status quo at Pobitora is changing. On 12 March 2023, environmental activist Rohit Choudhury approached the Supreme Court due to the Assam government’s failure to implement the 1998 notification on Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary.

His petition sought the “handover” of the khas land to the forest department, as mandated by the notification. Additionally, it requested declaring the surrounding area an eco-sensitive zone, removing encroachments, and stopping illegal activities within the forest zone.

The khas land, according to Choudhury, remains inhabited due to the lack of boundary demarcation. Since it doesn’t fall under the forest department’s jurisdiction, it restricts the rhinos to a limited area within the sanctuary, preventing them from reaching higher grounds during floods. As a result, the rhinos are sometimes forced to seek shelter in nearby villages.

The 17 March 1998 notification that declared Pobitora a wildlife sanctuary covered 15.84 sq km of Pobitora Reserve Forest (RF), 11.97 sq km of Raja Mayong RF, and 11 sq km of other khas areas.

Along with 336 hectares of Murkata I & II, the additional Khas land area included Diprang with 40 hectares, Thengbhanga with 176 hectares, and Kamarpur/Rajamayong Courtier Khas land with an area of 552 hectares.

But in the following quarter of a century, neither the district administration nor the forest department initiated any official procedures for boundary demarcation. It wasn’t until late last December that the Morigaon district revenue department finally transferred two village grazing reserves, Diprang and Thengbhanga, to forest authorities.

Then, in a surprising turn of events on 10 March this year, the Assam state cabinet decided to “withdraw” the 1998 notification, claiming that the Forest Department lacked jurisdiction over the government khas land and that the rights of those affected were not fully addressed.

There are people who are holding miyadi patta land, dating back to the 1930s. They owned land in Pobitora wildlife sanctuary much before the notification came out

-Devashish Sharma, Morigaon DC

The cabinet note stated that the 1998 notification “should have been issued after due consultations with other concerned departments and addressing the rights of all affected people in a lawful and humanitarian manner.” It also emphasised that those living in fringe villages should be considered “active partners” and not treated as adversaries.

All things considered, the Supreme Court issued a stay on the cabinet’s decision while hearing Choudhury’s case. It also clarified that this order wouldn’t prevent the state from “doing something to protect the rights of the forest dwellers” and directed the state to file a detailed counter-affidavit.

All hopes in pattas, govt scheme stamp

Unease has gripped the region following the Supreme Court’s stay order, extending even to those not directly impacted. Residents of nearby revenue villages are keeping a wary eye on the fleets of government vehicles and officials touring the area in the past few days.

Those living within the designated sanctuary area, like Murkata-I and Murkata-II, find themselves sinking deeper into the quagmire. There are rumours of impending indignities and evictions. Farmers, growing primarily boro rice as well as maize, mustard, vegetables, and watermelon, fear for their livelihood.

Local residents estimate that Murkata-I and Murkata-II, have around 500 and 1,000 households respectively. Bengali Hindus make up the predominant population across this 336-hectare (3.36 sq km) area. Besides these two villages, other settlements within the khas land areas include Kamarpur, Gobhali, Naloni, and Dhipujijan.

Murkata II’s Biswas, a farmer belonging to a Scheduled Caste, fears eviction from his land once the boundary handover is complete. But like many of his neighbours, he draws solace from his miyadi patta, a land ownership record. Many here got their pattas in 2000, but others have held theirs for longer, he claimed.

“Some of these pattas even date back to the 1950s,” Biswas added. “Brindabon Master [a village elder] has one—I’ve seen it. We arrived much later.”

Morigaon DC Sharma confirmed that some of the affected villagers possess land records even older than that. “There are people who are holding miyadi patta land, dating back to the 1930s. They owned land in Pobitora wildlife sanctuary much before the notification came out,” he said.

The land holdings are fragmented and the authorities are still trying to find a solution to the thorny problem before them.

Pobitora cannot survive without people. And people cannot survive without Pobitora

-Atabuddin Ahmed, resident of Khulabwuyan village

–

“We will need to find out a way—to identify people who are holding Miyadi plots of land, give them due compensation, and handover to the forest authorities whatever agricultural government Khas land is available,” he said.

ThePrint attempted to reach Mahendra Kumar Yadava, special chief secretary (Forest), for a statement via phone, but received no response.

Among residents, those availing of central and state government schemes seem most confident about their staying power, drawing a sense of legitimacy from their beneficiary status. Many people in the fringe villages have been utilising government-provided ration cards, LPG cylinders, and electricity for their homes. Some have even managed to build houses under the Pradhan Mantri Gramin Awaas Yojana (PMGAY) scheme. Biswas said “a chosen few” have also benefited financially under the state government’s Arunodoi Scheme launched in 2020.

Others, however, have their doubts, such as Joychand Mandal of Murkata-1. A 70-year-old, he still works as a manual labourer, cycling to work at 7 am and often returning after dusk. Mandal owns a land patta, but remains nervous.

“I don’t have cultivable land, but I have a land patta. I’ve lived here and hauled sacks at Mayong Bazar for as long as I can remember. But I haven’t availed any schemes,” he said.

Meanwhile in Khulabwuyan village about 5 km away, 43-year-old Atabuddin Ahmed declared that villagers were willing to “sacrifice their lives” to protect the sanctuary, but not their land. “Pobitora cannot survive without people. And people cannot survive without Pobitora,” he said.

How Pobitora became a sanctuary

For those seeking magic spells and mystical stories, Mayong beckons. This region, encompassing the Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary, is famed for its folklore, occult practices, and spiritual healing traditions. But it offers a lot more now.

Over the past five to seven years, Raja Mayong village, the main base for sanctuary visits, has witnessed a boom in development and tourism. Eco-resorts have sprung up, visitors throng souvenir shops selling local handicrafts, and jeep safaris ferry families eager for wildlife sightings. Amid all this activity are reminders of the nearby wilderness, such as the squawking of an oriental pied hornbill searching for its mate.

Though clear documentation is lacking, this village was once part of a small kingdom, established in 1538 by the Kachari kings. Legend has it that Pobitora received its name from King Xunyata Singha’s daughter, Princess Pobitora (Pabitra), after her untimely death. The erstwhile raj haveli of the royals, an Assam-type structure, still stands near the sanctuary headquarters. The push for Pobitora’s protection and the conversion of surrounding grazing lands into a wildlife sanctuary came not just from the royal family but also from a more educated public. This change coincided with the arrival of new residents in the region, both one-horned and human.

The indigenous Assamese population in the region is primarily composed of the Lalung and Karbi tribes. However, the settlements have become more diverse over time, especially with Bengali Hindus and Muslims arriving at various points in history.

Bhupen Talukdar’s Assamese book Bone Bone Mone Mone (translating to ‘silently in the forests’) details the arrival of Nepali cattle grazers in the foothills near the Kolong river around 1923-25. He further mentions grazers from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who began settling in the Buraburi area under Mayong circle since 1950. This area is currently home to a predominantly Bengali Muslim population.

In the 1960s, with the immigrant population growing exponentially, there was also a perceived rise in cases of theft and dacoity. Troubled by it all, in 1964, the king of Mayong rallied for Pobitora to be protected as a Reserve Forest. Earlier as well, villagers had requested the government to safeguard the few rhinos that had migrated from nearby areas. In a 1994 publication by the Asam Sahitya Sabha, LK Hazarika, the chief conservator of forests in Assam at the time, mentioned that Pobitora had 14 rhinos in 1961-62.

Following repeated requests, the government took action. On 18 November 1971, Pobitora was declared a Reserve Forest. A proposal to include specific areas within the sanctuary followed in July 1987, following which the forest department notified it as a wildlife sanctuary in 1998.

But the human settlements kept growing. Takukdar, who became the sanctuary’s ranger in 1992, recalls the khas lands within Pobitora being uninhabited during his tenure, unlike today.

The entire riverine belt of Brahmaputra — from Sadiya to Dhubri — was originally a rhino habitat until people began settling there, according to reports.

Living with rhinos

Parimal Sarkar had an unforgettable start in Murkata-II village. In 1988, on the first day that he arrived here from a nearby chapori (low-lying, flood-prone riverbanks in the Brahmaputra basin), he spotted his first rhino.

“The chapori we lived in eroded away during floods, and we moved to take shelter here. I saw a rhino the day I landed here. There weren’t many around that time. They don’t take this route as often now,” said Sarkar, 62.

A forest official attributed the change in rhino movement to the continuous roadside railings installed by the PWD department to reduce accidents. “But sometimes, they still take the route through a box culvert to raid crop fields,” he added.

Until 1971, the area was a grazing reserve. In Bone Bone Mone Mone, Talukdar writes that the first rhino appeared in Pobitora “sometime around 1923-25”, likely during the monsoon season. The rhino had travelled from the adjacent Laokhowa grasslands on the south bank of the Brahmaputra in Nagaon district. Escaping floods, it attempted to reach the Mayong hills, but was reportedly killed by villagers.

The entire riverine belt of Brahmaputra — from Sadiya to Dhubri — was originally a rhino habitat until people began settling there, according to reports.

Like Sarkar, Gayanath Biswas and Lal Mohan Choudhury moved to Murkata II between the late 1980s and 90s, when the landmass between the Brahmaputra and Pokoria rivers in Morigaon was washed away in floods. They eventually settled on the khas land in the sanctuary’s periphery.

As years passed, more families trickled in and settled on the fallow land. They began farming, building houses, and raising children. Eventually, they also learned to coexist with wildlife. It hasn’t been easy, but villagers still follow the rules when encountering a rhino or buffalo crossing the fields—they ensure safe passage for the animals without causing any disturbance.

Even today, the villagers believe that a rhino crossing the field brings good luck and an abundant harvest.

Also Read: Cheetah Mitras are the ambassadors of Modi’s Kuno dream. They have been on the frontlines

‘Partners in conservation’

With animals and people both vying for space in Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary, the Assam government’s proposed solution is to transform villagers into the frontline defenders of the burgeoning rhino and buffalo populations, a system that many conservation activists and NGOs have been advocating for. Such initiatives have had mixed results, but there have been notable successes, such as the reduction of poaching in Rajasthan’s Ranthambore with the help of community interventions.

In the 10 March meeting, the cabinet suggested that villagers be made “active partners in wildlife conservation”. It’s an approach that some wildlife experts have recommended as well, including Bibhab Talukdar, CEO of the wildlife NGO Aaranyak and chair of the Asian Rhino Specialist Group.

“These people are engaged in cultivation. The Forest department can pay compensation to the people if rhinos stray into paddy fields. They can be, in turn, told not to disturb the rhinos,” he said. “The purpose is to save the rhinos of Pobitora, and one way of doing so is maintaining good relations with the villagers.”

However, while villagers view rhinos as symbols of good luck, they are less kindly disposed toward buffaloes, which have been more frequently involved in human-animal conflicts.

“If the population of buffaloes increase, they will stray into human habitats — we have lost two persons to buffalo attacks this year,” said Dharma Biswas, 65, from Dhipujijan Pam village bordering the sanctuary’s western boundary. “This time, a large number of buffaloes have strayed out of the sanctuary and their population keeps growing.” He fears expanding the protected area could worsen conflicts with buffaloes.

According to Bibhab Talukdar, however, Pobitora’s wild buffalo population rarely interacts with humans. A survey is underway to understand their behaviour, and an awareness camp will soon be held, he added.

To manage the rising rhino population, the conservationist suggests treating Pobitora’s current rhino population as a source and relocating the rest to other sanctuaries within Assam.

“There’s little scope of expansion in Pobitora. Within the nearly 16 sq km of sanctuary area, the need is to have proactive grasslands management and keep the rhino population to around 90-100. If it exceeds this, there will be a spillover effect and rhinos will stray out,” he said.

Pobitora is endowed with 70 per cent grassland, 15 per cent woodland, with the remaining area taken up by water bodies.

To address human-animal conflict, the forest department has built temporary observation posts, called tongis, near animal corridors and deployed night patrols to monitor rhino movement outside the sanctuary, said a forest official. Captive elephants are sometimes used to guide stray rhinos back to their habitat.

Previously, villagers illegally collected firewood and thatch from the sanctuary, but this practice has stopped. Sarkar, a resident of Murkata, fondly remembers a former ranger who assisted villagers with wood and bamboo poles for religious events like Durga Puja.

“Our relations with the forest department are cordial. We also have friends who are foresters. Around the year 2000, we would request the ranger for some bamboo to set up the Durga Puja pandal at the temple. He was kind… We would carry the bamboo from Bura Mayong.”

The forest department also relies on villagers for intelligence to combat poaching. Village Defence Parties act as the first line of defence, and some villagers serve as informants. But there have also been dark moments.

In Kukuwari village, located barely 200 metres from the forest camp, rhino poacher-turned-conservationist Esob Ali was reportedly murdered by his adversaries in 2014 for providing information.

The village was once notorious for crime, including poaching, banditry, and other illegal activities. While there is now more education and development here, Ali’s family is still struggling to make ends meet. His son, 25-year-old Dildar Hussain, helps his mother in husking betel nuts for a living, but aspires to work for the Forest Department.

“My father gave protection to rhinos. I followed his footsteps, thanks to some officers who absorbed me as an informer for six years. I was later asked to leave for being irregular. But I am ready to serve once again, whenever I get a chance,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)