Kuno: The song to hail the exhilarating arrival of the cheetahs from Africa into Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park was written a year ago. “Ke cheetah aa gaye Kuno, dhaang sakhi ab suniyo”—Oh friends, have you heard cheetahs have come to Kuno?—became the anthem of the army of ‘Cheetah mitras’ or friends of cheetahs. They are ambassadors of a new Modi dream. And they are practising for the anniversary celebrations on 17 September to mark one year of Project Cheetah.

A lot has happened in the past year. Of the 24 cheetahs, nine have died. And numerous questions have been raised about the ambitious project by experts and opposition parties alike. But what has not dimmed is the boundless enthusiasm of cheetah mitras like 18-year-old Kavi Bharadwaj. His yellow t-shirt with ‘Cheetah Mitra’ written on it is now faded, but he wears it proudly as he sings the song in the small forested Karahal village and gestures to his friends to join him. Kavi’s song, which his father had written, has new verses about the past year, and how the cheetahs have been adjusting to their new home.

From bringing food for range officers on a cheetah’s trail to preventing villagers from cutting trees in forests, drumming up excitement and dispelling myths about predators preying on cattle, the cheetah mitras are at the frontlines. Foot soldiers and evangelists working with no pay.

“This isn’t like a regular job for us. We don’t do it out of obligation. Whatever we do, it’s out of our love for the country, and for the cheetahs. We just hope the project is successful,” says Kavi. But his smile falters as he recalls deaths inside the national park.

Cheetah Mitras are the first responders when a big cat strays out of the national park, and help track the animals that sometimes cross state borders into Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. They alert forest officials about sightings and allay the fears of frightened villagers. They are the bedrock of local involvement in the project.

If ever a cheetah needs us, I can gather people and arrive at a moment’s time – Kavi Bharadwaj

Hundreds of able-bodied men from local villages around Kuno were recruited by the Madhya Pradesh Forest Department to act as Cheetah Mitras. For one year, they have been working alongside the forest department travelling from village to village to talk to villagers and dispel myths. But their numbers, too, are dwindling.

“We started with 400 cheetah mitras, across all villages near Kuno,” says Raj Ojha, who joined as a cheetah mitra a few days after the animals were brought into the park. “Now, there are only about 40 of us, and still some people don’t work, don’t show up to meetings,” he says.

Also Read: ‘Ecologically unsound, costly, distraction’: Conservationists slam India’s cheetah project

Shroud of secrecy

The cheetah mitras may be the BFFs of the big cats, but like the rest of India, even they don’t know what’s happening within the national park, and why the cheetahs are dying.

Secrecy shrouds Project Cheetah, which villagers had been promised would increase tourism and put Kuno National Park on the international map. As diffidence morphs into disillusionment, hundreds of villagers who were relocated to make space for their foreign guests, are questioning the cheetah mitras about the project’s future. But the mitras have no answers to give them.

And this makes the cheetah mitra programme a non-starter, argues wildlife biologist and conservation scientist Ravi Chellam.

“Local communities should have been involved from the planning stage of the project itself. The cheetah mitras deserve access to the cheetahs and information related to the project in real time,” he said.

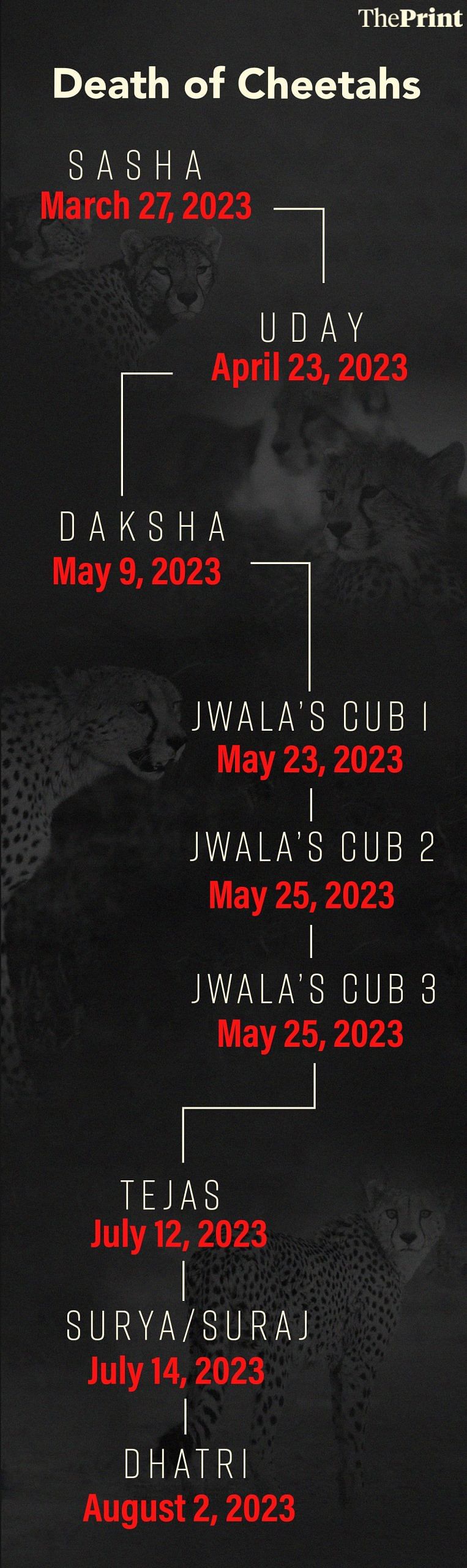

The first cheetah died in Kuno on 27 March, barely six months after being brought in from Namibia. By the first week of May, adults Uday and Daksha also died, and by the month’s end, the country mourned the deaths of three cubs born to Jwala. Six cheetahs had died in three months. As the mortality rose, so did the uneasiness within the local communities.

The cheetah mitras, who were tasked with taking care of the cheetahs, weren’t even aware of the deaths.

“We weren’t told by the forest department when the deaths happened, or why. We only found out when the news reports started coming in,” says Hari Om Kushwaha, a 25-year-old cheetah mitra, who runs a small grocery store in Karahal.

Many are smarting over this information gap, which—along with the lack of financial support—could explain why cheetah mitra numbers have dropped. They are expected to track cheetahs across villages, often spending their own money and resources. They are sometimes also asked to provide food for forest rangers who are on the trail of an errant cheetah.

This culture of secrecy has allegedly filtered through the rank and file of the forest department in Kuno.

Phones ringing off the hook, hushed tones, and files marked ‘confidential’ in the DFO’s office lend themselves to the atmosphere of silence that has settled over much of Kuno. “We aren’t at liberty to say,” is the go-to response from any forest official in the region.

“Around two months ago we were all made to sign a form that said there could be police action against us if we spoke of the national park and the cheetahs to people outside,” alleges a forest guard.

Kuno divisional forest officer, Prakash Verma says that guards and trackers have been told not to discuss matters of the park to outsiders. “We had also told them there could be police action if they spread rumours or misinformation about the cheetahs. But there was no written order or contract about this,” he adds.

Also Read: Cheetah is India’s new conservation icon after tiger. It can save grasslands

No financial support

Kavi remembers the first time he tracked a cheetah that had strayed from the park in July. Nirbhaya had been untraceable for weeks, and hope was dying.

But suddenly her radio collar activity pinged somewhere around Karahal in Aamjet, a small hamlet barely 30 kilometres from Kavi’s house. When the range officer called him to inform him of Nirbhaya’s whereabouts, he immediately rushed to his friends.

“We used to go to the Shiv temple in Aamjet a lot, so we knew the area. A few of us got on our bikes and started driving towards it,” he recalls.

On their way, they thought of the key points of tracking a cheetah taught to them: inform local villagers and the forest rangers, and keep a safe distance from the animal. Kavi called the sarpanch of the village and asked him to prevent others from going toward the Shiv temple. He also made sure that they parked their own bikes at a safe distance so as not to alarm the animal.

They tracked Nirbhaya on foot early in the morning and found her playing at the waterfall near the Shiv temple.

“Surprisingly, I wasn’t scared of her. I instead felt relieved, because after weeks we had finally found her,” says Raj, who was accompanied Kavi. They stood guard, 20 feet away from the cheetah, until the forest department team arrived.

Raj and Kavi watched from afar as the rangers put a baby goat next to a cage to lure Nirbhaya. They easily secured the cheetah, and no harm came to the baby goat either.

“Without using a tranquiliser, the vets and rangers took her away safely in a large cage. She didn’t even protest much—like she was already friends with them,” says Raj.

It’s a story they will tell their children one day, but nobody talks about the financial toll this ‘job’ takes on them. Even those who have their own vehicles struggle to pay bills.

If we do not provide them with economic rewards that come from cheetahs, people’s interests in conservation will soon dwindle

– YV Jhala, former principal scientist, Project Cheetah

“Some people cannot even afford the petrol for their vehicles. How can we ask them to work for free,” asks Raj, who works in a confectionary store outside Karahal.

Experts, conservationists, and scientists commended the government for including local communities in the project, but pointed out that effort is wasted if they are involved only in name.

“If we do not provide them with economic rewards that come from cheetahs, people’s interests in conservation will soon dwindle, and conservation will only be esoteric and elitist,” says YV Jhala, retired dean of the Wildlife Institute of India, and former principal scientist of the Project Cheetah.

Cheetahs were once present all over India. Neolithic-era ave paintings in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh depict the big cats.

Their decline began during British rule. Colonial administrators viewed them as a threat to livestock.

The last cheetah is reported to have died in 1947.

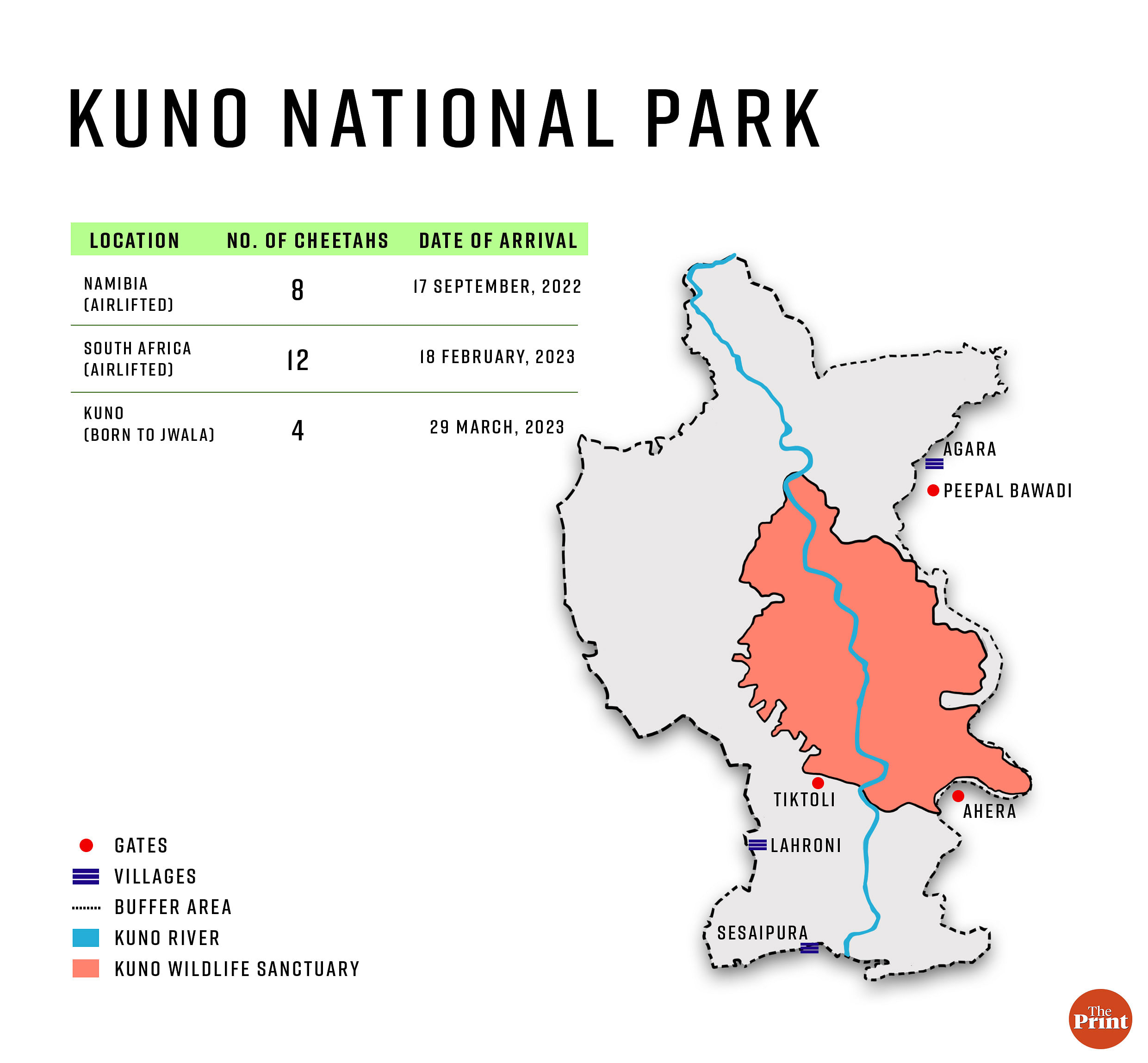

According to the Cheetah Action Plan, Kuno National Park was chosen due to “its suitable habitat and adequate prey base”.

Jhala played a key role in designing the programme and bringing the cheetahs from South Africa and Namibia to India. But his contract with the Wildlife Institute of India was unexpectedly terminated in February and he was ousted from the programme that he devoted a decade of his career to.

“It is already late, but some form of revenue generation is required. More importantly, that revenue should be shared with local people. Otherwise, cheetahs cannot have a future in India,” he adds.

Cheetah tourism

At Agara village, residents still chuckle over the ‘unplanned’ and ‘unsanctioned’ encounters they have had with Kuno’s cheetahs, mostly crouching in their fields.

“Around four months ago, one of the cheetahs, maybe Asha, was found near the temple in our village. While the cheetah mitras were alerting the forest department, I ran there at full speed,” says Ramlal Adivasi, smiling.

There are 55 villages near Kuno, which itself spans around 748 square kilometres. Tiktoli, Peepal Bawadi, and Ahera are the three main gates to the Park, located at the southern, northeastern, and eastern regions of the park respectively. Ramlal’s Agara village is nestled in the northern edges of the park, towards the Peepal Bawadi gate.

“I thought I should at least catch a glimpse of the animal for which we gave up our forests,” Ramlal adds.

Many villagers recount the days before the arrival of the cheetahs when the forest department’s rangers would come to talk to them about Project Cheetah. They explained the difference between cheetahs and leopards and emphasised how the first cheetahs of India being in this region would elevate its importance.

“Neither have any tourists come this way nor have our boys gotten real jobs. In fact, some of them have lost their jobs with the forest department arbitrarily,” says 75-year-old Babulal Kushwaha, whose family was displaced in 2000 to make space for the Kuno sanctuary. The current enclosure for the cheetahs inside Kuno rests exactly in the area that was once his family’s house.

Conservation scientists are divided over whether the cheetah enclosure should be opened to tourists. Some like Jhala make a case for tourism.

“Ecotourism is crucial. It has now been a year, and we haven’t shown cheetahs to anyone, let alone the people who live near them,” he said. But others argue that among the big cats, tigers, leopards and cheetahs are fragile animals.

“Cheetahs are not sturdy, even if they have small scratches, they need to be attended to immediately. So, before beginning regular human interaction with tourists, we need to properly monitor them,” says DFO Verma.

Nine of Babulal’s sons and nephews are cheetah mitras, and also work with the forest department as trackers and forest guards.

According to Verma, the department has hired almost 60 trackers from around Kuno’s villages. Unlike the cheetah mitras, the trackers are allowed entry into the park and are paid Rs 9,000 a month. It’s their job to track the animal when it’s allowed to roam in the wild. Each cheetah was assigned a team of four people—a tracker, a driver, and two forest guards.

But after all the cheetahs were brought back into the enclosure last month, many of the trackers were asked not to report to work.

One of them, on the condition of anonymity, says he had to work eight to nine-hour shifts daily and arrive at the forest whenever the department required him to.

“We could also sense when pressure mounts, because suddenly our hours would double, and our seniors would ask for updates more frequently,” he says.

But like the cheetah mitras, the trackers too are kept in the dark even when a cheetah dies. And when they are finally informed, they’re not allowed to discuss it with anyone, another tracker claims.

Bad meat and rumours

With cheetah mitras unable to meet the cheetahs they are creating awareness about, and cheetah trackers unable to talk about them, villages in Kuno are rife with stories of what killed the cheetahs. Suddenly, everyone from the mechanic to the farmer to the village elder is an expert.

In Sesaipura village, Lalu runs a small tea shop, bordering the road leading towards Kuno’s Tiktoli gate. He sees the forest department’s vehicles pass every day and is convinced he knows why six adult cheetahs in Kuno are dead.

“Bad meat,” he tells his customers confidently while pouring tea into tiny cups. “The forest department feeds the cheetahs bad meat. Now you’ll see, the rest also won’t survive much longer. How can they, with such poor caretaking?”

He couldn’t be further from the truth, but with no information forthcoming, villagers and visitors have latched on to this.

In the same vein, former dacoit Ramesh Sikarwar tells his relatives that he left his role as a cheetah mitra because of the mismanagement of the forest department. At his farmhouse in Lahroni village, the 78-year-old sits astride a cot, clutching his rifle. His luxuriant moustache and an old-time bandolier that he wears across his chest give credence to his theories.

Sikarwar was one of the 400 cheetah mitras to be initially inducted by the forest department. He claims it was because people in the forests feared him from his time as a dacoit in the Chambal region during the 1970s.

“They wanted someone who would stop people from hunting cheetahs, and I was top of the list. The forest department knows my reputation in the jungle, even today,” Sikarwar says.

He says he left the project of his own volition.

“When I found out about the way cheetahs are being treated, I left the ‘cheetah mitra’ post right away. I don’t want anything to do with the project,” he says.

It’s not true. According to Prerna Dubey, a range officer with the Kuno forest department, anyone over the age of 45 was removed from the post of ‘cheetah mitras’ two weeks into the beginning of the programme. This was done so that younger boys would be given a chance to engage with the project. Physical stamina was another factor.

Sikarwar, however, has another tale to tell.

“If they had let me and other cheetah mitras take care of the animals, none of them would have died,” he says.

Back in his office in Sheopur, the DFO Verma shakes his head in frustration over the false news that refuses to die.

“This [bad meat] was a rumour that started around two months ago, with the deaths of two cheetahs from infections of their radio collars. There was little we could do before it had spread across villages, and we were hearing about it from our officers,” he says.

The department has a team of trained experts, veterinarians, and international wildlife experts monitoring the cheetahs. There’s a lot riding on the project that wants to reintroduce the big cat back into India’s wild.

“I mean, it is ridiculous to even think this story is true,” he says. But the irony is that the forest department’s own opaqueness allowed these rumours to take hold.

This silence is unusual for the Madhya Pradesh forest department; senior officials of other divisions say they have often welcomed journalists and NGOs, and especially local communities to collaborate with them. But the arrival of the cheetahs has changed this.

Neither have any tourists come this way nor have our boys gotten real jobs. In fact, some of them have lost their jobs with the forest department arbitrarily – Babulal Kushwaha, villager

Verma and his team are working round the clock to monitor the animals. Consisting of four ranges, the Kuno Forest Division is wholly dedicated to the cheetahs and other wildlife in the region. They have set up around 50 camps inside the national park, to house forest officials tracking the health and welfare of cheetahs.

“We are also doing this for the first time. Every day there are new challenges and we’re trying to combat them as they come — to not disappoint the country, and ourselves,” said DFO Verma, while talking about the intensive training they went through before the coming of the cheetahs.

As the eve of the one-year anniversary of the cheetahs’ arrival draws closer, the forest department is working double time to ensure both the well-being of the cheetahs and of local faith in the project.

Also Read: ‘Speed of a cheetah’ — read the subtext. Modi’s ‘pet’ project is heavy with political messaging

Reminder of the wins

Kavi still remembers the day he became a ‘cheetah mitra’, and was present inside Tiktoli gate when the big cats arrived in the Kuno National Park. He took with him a copy of his song “ke cheetah aa gaye Kuno, dhaang sakhi ab suniyo” to recite for Prime Minister Modi at the event. “The Prime Minister liked it so much that he asked for the copy to keep with himself,” he recalls.

The young man is at the forefront of organising awareness campaigns in his range of cheetah mitras. He says that he is always in touch with the Range Officer on WhatsApp, so that “if ever a cheetah needs us, I can gather people and arrive at a moment’s time.”

Working on the project has taught him a lot about wildlife conservation, and even about the work put in by the forest department.

He has big plans for the one-year anniversary. “We will be planning performances at every village. I know people are a bit disheartened now, but we should give the department time, it has only been a year,” Kavi says. “People need to be reminded of our wins – we’ve stopped hunting in the forest, we have reduced deforestation.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)