Vachathi: A group of Adivasi women walk toward their village’s lakeside cradled in the peaceful foothills of the dense Eastern Ghats. They don’t like to frequent the scenic spot. It is where they were held down, beaten, and raped 31 years ago by khaki-clad state officials.

The 18 women from the tribal village of Vachathi in Tamil Nadu’s Dharmapuri district have retraced these steps a thousand times before, trying to convince people that the horrific crime happened. They were called liars and criminals, accused of smuggling sandalwood and protecting the forest brigand, Veerappan. Their homes were destroyed, their village well was contaminated, their animals slaughtered. Their husbands, children, parents and friends were beaten and illegally detained.

The Vachathi case has gone down in history as a massive failure of the state. And today, the villagers want the government to correct its wrongs.

They’ve spent the past 31 years fighting for justice. And while a historic judgment passed on 29 September 2023 upholds the guilty conviction of the hundreds accused, it’s not enough for the generations destroyed by their crimes.

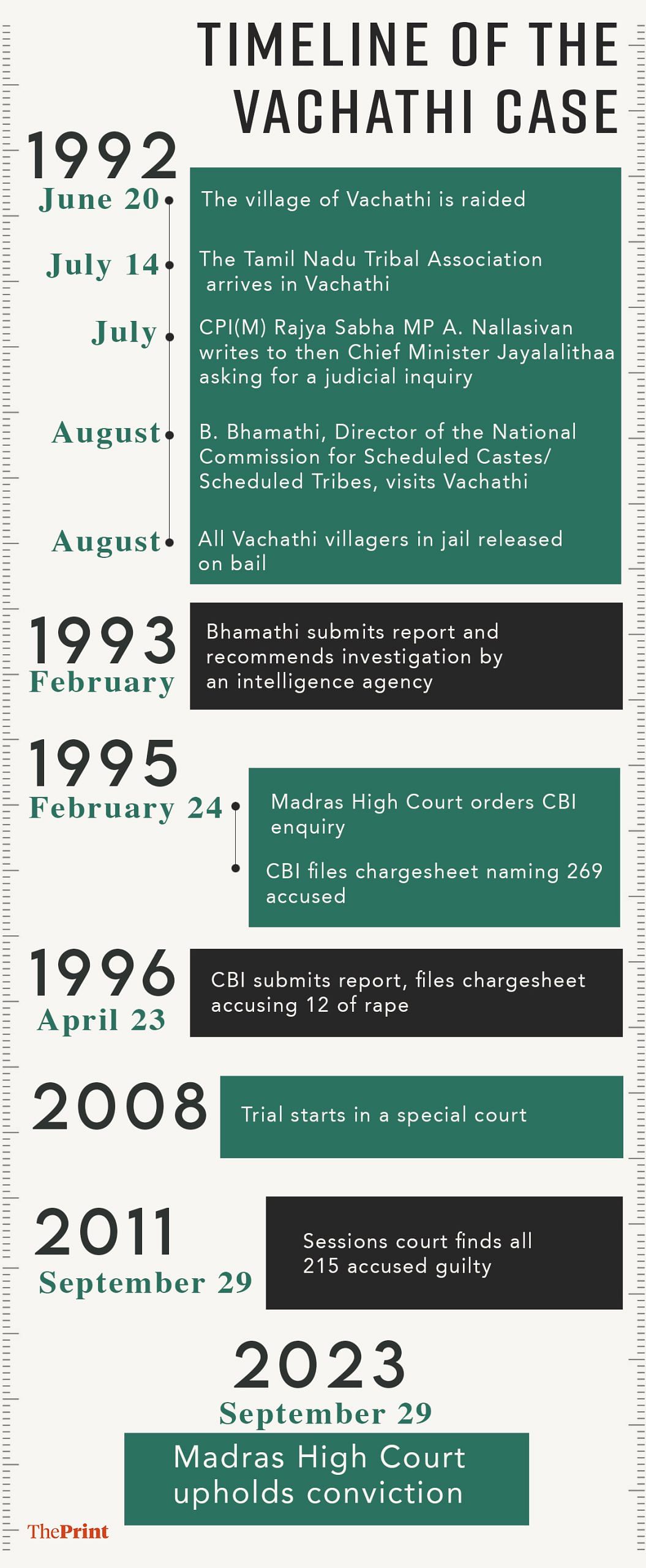

The villagers of Vachathi were attacked on 20 June 1992 by 269 uniformed men from the police, revenue and forest department on the pretext that they were smuggling sandalwood. Eighteen women were carted to the lakeside and sexually assaulted for hours. It took 19 years for a trial court to convict 215 men, but by then, 54 of the 269 accused had died. Exactly 12 years later to the date, the Madras High Court upheld the conviction and directed the state government to pay a compensation of Rs 10 lakh each to the eighteen rape survivors and ensure a government job to a family member. The court added that 50 per cent of this amount must be recovered from those convicted of raping the women.

“There is no price for a happy, dignified life,” said Padma angrily, tears suddenly brimming in her eyes. She was only 17 when she was raped, and her sister was barely 13. “Those who attacked us are all from the government — they were the ones who destroyed our homes and our lives. It’s their duty to right their wrongs.”

Now, Padma and the rest of Vachathi are asking for what they are owed. They want schools, primary health care centres, and roads to be built for their village and all the other hamlets around the foothills of Chitteri Hills. They want land rights and better houses. They want dignity and stability.

The villagers of Vachathi are well aware of where they stand in India’s social order — they have experienced firsthand cruelty at the hands of the state. The men who were supposed to protect them — the Forest Department, the Police Department, the Revenue Department — did this to them.

The pain and humiliation of those months in 1992 are still very much alive in Vachathi today. It didn’t end with the rampage but continued as they fought to be heard by the state authorities.

When they went to the government for help, they were accused of lying. It took two weeks before news of the crime made its way to the mainstream and three years for a chargesheet.

When the Communist Party of India (Marxist) raised the issue in the Tamil Nadu assembly, then-All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) Chief Minister Jayalalithaa denied that such a thing could happen, and accused them of defaming her government.

The judgment has amplified their truth.

“This is a historic judgment because all of India will think twice before exploiting tribal peoples,” said P Shanmugam, leader of the Tamil Nadu Tribal Association (TNTA). “It has driven home the point that however high an official you are if you commit a crime, you will be punished.”

The women’s 31-year fight for justice is paved with grit, resilience and solidarity. It truly took a village: The CPI(M) and the TNTA fought alongside them from the very beginning, attending every single hearing and helping the illiterate, impoverished villagers navigate a legal system stacked against them.

It has driven home the point that however high an official you are if you commit a crime, you will be punished

– P Shanmugam, TNTA

“These people have survived despite being put through hell,” said lawyer R Vaigai, who is a part of their legal team. “Instead of being desolate, they were able to steel themselves to become role models, policymakers, and instruments for change. It’s an inspirational story, because at no stage did the government contribute to helping them get justice,” she added.

Also read: Bhanwari Devi was raped for trying to stop 1992 child marriage. ‘I curse her daily,’ says bride

Anatomy of a crime

When Shanmugam arrived at Vachathi on 14 July 1992, the village was deserted—silent like a burial ground at night. There was evidence of human life, but no people to be found.

Shanmugam was then general secretary of the newly formed TNTA, which had held a meeting at the foothills of the Chitteri Hills earlier that month. Two villagers from Vachathi—who escaped the police—had attended the meeting. It was the first whiff that something terrible had happened.

Vachathi is a tiny hamlet located near the town of Harur, in Tamil Nadu’s Dharmapuri district. It’s one of several hamlets along the foothills of the formidable Chitteri Hills, which forms a section of the Eastern Ghats. At the time, there were around 186 households and 600 residents in Vachathi. It was by no means a small village, but it was remote and disconnected.

Nothing could have prepared Shanmugam for what he found when he arrived. Houses were demolished. Roofs had been forcibly caved in. Torn clothes, broken utensils, and smashed containers of food lay strewn around the debris. Sacks of rice and ragi had shards of glass and kerosene.

The only source of water in the village—a well—was contaminated with oil, kerosene, blood, and the entrails of slaughtered animals.

And there was not a soul in sight.

It took him three hours to find at least 45 people. Some were hiding, trembling in bushes, others too scared to speak. Over the next few days, the CPI(M) spent hours coaxing villagers out of the hills, waving the red party flag to tell them they wouldn’t be harmed.

And slowly the extent of the atrocity began to be pieced together.

The residents of Vachathi were rounded up and forced to assemble in front of a large banyan tree in the middle of the village. Eighteen women—including a 13-year-old child and a heavily pregnant woman—were handpicked to show the forest officials and police where they were allegedly stashing the smuggled sandalwood.

Dragging them by their hair while they begged and screamed, the women were bundled into a lorry like cattle. The lorry trundled down the singular road for barely 50m, before it veered off toward a large lake.

The 18 women were dragged through thorny bushes that tore through their flesh. And then they were beaten and raped, again and again, in the dark. They couldn’t see the faces of the men brutalising them. All they remember is the pain, the thickets, the thorns, and the sound of wails.

Then they were dragged back into the lorry and driven to the Forest Rangers Office in Harur—the town closest to Vachathi, about 30 minutes away—and illegally detained. There, they were tortured again.

They were forced to drink urine and eat off the bones of meat already devoured by the policemen. They were made to hit their village elder with a broomstick, skinning him alive. If they refused, they were beaten instead. They weren’t allowed to speak or even look at each other that night.

Lakshmi, who was 15 at the time, remembers being too terrified to even look up. She was made to eat rice that had been chewed and spat on the floor. They were forced to kneel in front of a pile of sandalwood and photographed. They were threatened to not open their mouths in front of the judge while being remanded. The next day, they were transferred to the Salem women’s jail.

Those who attacked us are all from the government — they were the ones who destroyed our homes and our lives. It’s their duty to right their wrongs.

– Padma, rape survivor

It was there that they met the 90 other women and 28 children from Vachathi who had also been earlier picked up and illegally detained. When a mother asked for water for her infant, a police officer urinated in a cup and gave it to her. Another mother gave birth to her child in jail.

Perunthayi, now in her 70s, had been tied up and beaten so much that she had to constantly move to prevent her blood from clotting. Around 15 men were lodged in the Salem central jail. This is where they stayed for the next three months, with no idea of what was happening to them.

Back home, the other villagers who had fled to the hills survived on nothing but what the forest offered them for weeks.

Until help arrived in the form of Shanmugam and the TNTA.

“It was the first and most important issue we have ever been involved in,” said Shanmugam, his eyes clouding over with anger. He has spent exactly half his life fighting this case, and he still cannot digest the extent of the crime. He’s visited the village countless times from his field office on the outskirts of Chennai, spending weeks at a time during the early days of the case. He’s attended every single trial over the last 31 years.

“There have been hundreds of petitions, and hundreds of days on trial. So…it has been a long fight,” he said with a tired smile.

Rampage as revenge

It started as revenge for a perceived slight.

The villagers all belong to the Malayali tribe, the main Adivasi group in Tamil Nadu. Most of them were engaged as labourers, as they are today. They still swear they had nothing to do with Veerappan.

But Vachathi is deep in what was once Veerappan territory—where he was feared and revered in equal parts. Sandalwood smuggling was rampant, and state authorities were under pressure to stop him.

On the morning of 20 June, a team of forest officers visited Vachathi and announced they were going to investigate the village for smuggling sandalwood. The first person they spoke to was Perumal, an old, deaf man who didn’t follow what they were saying.

An officer slapped him — and a younger man came to his defence. A tussle ensued, after which the villagers took the injured forest officers to the hospital in Harur.

That evening, nearly 300 uniformed men arrived in the village.

The officials said the villagers surrounded them and beat them up, injuring 22 of them. They claimed the villagers concocted their ordeal for sympathy, and that there was no proof that any of them belonged to any Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe.

Weeks later, when news of the atrocities started seeping into the mainstream, the government machinery also denied it. They were on “official duty” and hence their actions couldn’t be crimes.

The TNTA demanded to meet the district collector at midnight after visiting the villagers in jail. When he finally emerged, he said it was the first time he had heard about it. It had been 26 days since the raid took place.

“They were insulted, and wanted to take revenge!” said Dilli Babu, a CPI(M) leader who at the time was district coordinator. He was eventually elected as MLA for Harur district and served two terms.

“Not a single log of sandalwood was found in the village. The government in power had a problem with the forest department, and innocent tribals were caught in the crossfire,” he added.

The sandalwood nexus ran deep, according to Babu. Forest officials in collusion with smugglers —who allegedly had political ties to the AIADMK—hired villagers from the nearby hamlet of Kalasambadi to cut sandalwood.

When a few tonnes of this sandalwood went missing, the forest department used it as an excuse to raid Vachathi.

Even the Madras High Court’s landmark judgment acknowledged this nexus between the smugglers and the forest officials. “…It is clear that there were large number of smuggling activities of sandalwood but all were doing by the big shots with the help of the forest officials. Unfortunately these innocent villagers were made as accused,” read the judgment.

Also read: No one wants to talk about rapes in Manipur. There’s a silence at the heart of the violence

The hunted became the hunters

Sanku was working at the local post office in Harur when he first heard of the crime from the TNTA. A member of the CPI(M), Sanku spread the word through the rank and file of the party cadre.

But even they didn’t know that 18 women had been brutally raped. Shanmugam says he never asked women if the crime was committed. He didn’t need to—it was obvious when he saw them, huddled in shock in the corner of the jail cell.

The villagers were released on bail three months later. When 15-year-old Lakshmi returned to Vachathi, she remembers searching and screaming out for her father and her husband she’d married only a few months before the crime. They were partially in hiding, still too afraid to fully trust the CPI(M).

“My father heard my cries and came running toward me from the hills and told me to be quiet in case any officers heard me,” said Lakshmi. “This was the most I had used my voice in months.”

When she walked through the debris of her former home, the first thing she noticed was her wedding photograph, crumpled and torn beside the smashed frame. The glass from the frame lay scattered amid the grains spilling out of a torn sack. “Not even utensils or glasses were spared. There was no clean water because the well was contaminated, but if there had been, we wouldn’t have had anything to drink it from,” said Lakshmi.

It would take years for the full extent of the crime to sink in, and even more time for the villagers to regain their confidence.

The TNTA filed a public interest litigation, which was dismissed by a judge — Justice Padmini Jesudurai, also the first woman judge at the Madras High Court — who implied that educated people can’t commit such crimes. The CPI(M), led by A Nallasivan, raised the issue in the Tamil Nadu assembly in July — only for it to be dismissed by the AIADMK as a political move to besmirch them.

On the floor of the Tamil Nadu assembly, forest minister KA Sengottaiyan said the violence was fabricated and the raid was justified, because the villagers were criminal sandalwood smugglers.

Nallasivan then appealed to the Supreme Court, which ordered the Madras High Court to take up the matter.

At first, the demand was for a judicial enquiry to probe the acts committed in violation of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989. But not for rape because the survivors were still in jail at the time.

The high court constituted a single-person Commission of Inquiry, led by IAS officer B Bhamathi, who was then-director of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes. By that time, all the victims had received bail. Bhamathi submitted a detailed report alleging State brutality and multiple human rights violations. Finally, three years after the attack, the case was transferred to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in February 1995.

And a year and two months later, in April 1996, the CBI submitted its report and filed a chargesheet naming 269 men from the forest, police, and revenue departments. There were forest rangers, plot watchers, forest guards, police constables, tehsildars, and drivers. This list included the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF), Conservator of Forests, and the District Forest Officer.

But the CBI officers from Delhi didn’t list the district collector or the superintendent of police. These were IAS and IPS officers — “too senior and too educated to have taken part in such an atrocity,” said the CBI investigators, according to Shanmugam.

The case finally went to trial in 2008. The Madras High Court ordered a special court to be formed under the Krishnagiri Sessions Court. During the intervening years, multiple petitions were filed on both sides. The accused submitted that they were educated representatives of the state, and therefore not capable of such acts. The TNTA filed separate petitions for monetary compensation. The back and forth went on for years.

On 29 September 2011, the trial court convicted the 215 surviving accused of various charges under the SC/ST Act.

Every single one of those accused is intimately familiar with Shanmugam and Dilli Babu. “We were their hunters,” the two men said, chuckling at their head office in Tambaram on the outskirts of Chennai. The accused would come and beg them to drop charges, alternating excuses with apologies. But neither the TNTA nor the CPI(M) had any sympathy for them.

“In the history of the world, this is the largest number of uniformed persons punished by law,” claimed Shanmugam. “Exactly 12 years later, on the same date, their appeal has been dismissed.”

And for the first time, the 2023 Madras High Court judgment, delivered by Justice P Velmurugan, has named the district collector, Dasarathan, and the superintendent of police, Ramanujan — who would go on to become Director General of Police under Jayalalithaa —and called them out for ignoring the complaints about sandalwood collusion from Vachathi.

In the history of the world, this is the largest number of uniformed persons punished by law

– Shanmugam, TNTA

Also read: Manipur video sets Alwar gang rape victim back by 4 years. She wants right to be forgotten

The road forward

Thirty-one years ago, the villagers of Vachathi were rounded up under the banyan tree before they were carted away to be raped and illegally detained. Today, they’re gathering around the same tree to articulate their demands. The rape convictions have been upheld, but their fight for justice is far from over.

Mobilised by Babu and the CPI(M), the 18 women especially are staking their claim to restorative justice.

“I’m happy that the court has ordered [in our favour]—to get Rs 10 lakh,” said Mani, one of the survivors. “But Rs 10 lakh can also be spent.” Many of the villagers are in deep debt, having had to rebuild their homes after they were destroyed.

It’s only the rape survivors who are entitled to the money. The rest of the villagers haven’t received such specific compensation, though the government did rebuild tenements and set up new water sources and a ration shop over the years.

Now they want more.

Besides better road connectivity, pucca homes and a permanent supply of drinking water, villagers of Vachathi also want a higher secondary school to be built in nearby Kalasambadi to ensure equitable development across the hills. They also want the landless residents of Vachathi to be given 1-2 acres of land in their name.

Two nearby village hamlets still don’t have access to electricity, and the closest primary health centre is still a good 20 minutes away.

The generational disparity can be corrected with the promise of government jobs.

“What happened in this case is that the government was obstinate in denying any kind of relief to the people,” said lawyer Vaigai. “The village needs to be supported in other ways too. As a socially responsible state, why should the government wait for a judgment to do this,” she asked, pointing to the fact these demands are basic necessities for development.

When the village was destroyed, an entire generation of youth also lost access to academic records and their community certificates, forcing them to take up manual labour.

They also want skill development programmes. Women can then learn tailoring work so they can at least earn Rs 5,000-7,000 a month, said Babu.

“Speak to the leaders with courage and patience,” coached Babu as the women sit in front of him by the banyan tree one afternoon, a week after the Madras High Court judgment. Only 10 of the eighteen rape survivors still live in Vachathi, the others live in nearby towns.

“Give statements [similar to the ones] you gave [to] the court. Remember, not a single forest or police official has set foot in this village in over 25 years,” he added while the women listened intently.

They are gearing up for a meeting in Chennai with the CPI(M) leadership, which is also angling to meet Chief Minister MK Stalin to put forth these demands. Most of the survivors have gotten actively involved in local politics, and have become community figures in the area.

The women survivors are resolute. They know this is the fight that has defined their lifetimes. They are bonded in an irreplaceable way.

Even when they visit the spot where they were raped, they walk with camaraderie, shielding each other from the harsh sun with foliage while teasing each other about inanities. Lakshmi says she needs to go to Harur to pay off a moneylender, while Divya wonders if she should cook mushrooms the next day.

“We’ve had to live here, where all this happened,” says Vijaya indignantly in response to a question on whether she would ever leave Vachathi. “This is our home. We have nowhere else to go.”

Vijaya pauses for a moment, defiantly looking away from the lakeside in the shadow of the mountain and toward the village banyan tree.

A lone red CPI(M) flag, stark against the green canopied slopes of Chitteri Hills, flutters in the wind.

This is our home. We have nowhere else to go

– Vijaya, rape survivor

Every time they talk about the struggle, they mention CPI(M) leaders M Annamalai, Dilli Babu, Nallasivan, and TNTA leader Shanmugam. Several homes in Vachathi have the red communist flag tied to poles outside the door. Kannaghi, a district-level CPI(M) leader from a nearby village, has become a de facto sister to the women. Lakshmi remembers her as the first woman from outside the village to hold her, cutting through the stigma of rape.

“They are the only ones who gave us respect and care,” said 70-year-old Perunthayi, who refuses to sit around Dilli Babu as a mark of respect.

After the meeting to decide the agenda for the Chennai visit concludes, Babu returns to Harur while other local CPI(M) leaders stay in Vachathi for lunch—rice, rasam and a simple poriyal, cooked in Lakshmi’s kitchen. Clad in crisp white with the tiny red CPI(M) booklet visible through their shirt pockets, the men settle down to the meal served by Lakshmi and Kannaghi.

The women don’t even eat until their thozhar — comrades — eat.

Names of the survivors have been changed for anonymity.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)