Hyderabad: When Sai Krishna travelled from Hyderabad to Chandigarh to raise funds for his millet startup in 2016, he worried whether his products, like jowar porridge and ragi flakes, would be innovative enough to impress angel investors. Instead, he encountered the opposite problem. His offerings were seen as too unconventional.

“What are millets? Who eats them?” the investors asked. Taken aback, Krishna made his pitch but left disappointed.

Fast forward seven years, and millets have become the hottest ‘supergrain’ in town. From gracing Insta Reels to Diwali hampers to the G20 menu during India’s presidency, they’re playing a starring role. The UN declared 2023 the International Year of Millets and later dubbed them a “global superfood”. Last November, a song featuring Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s endorsement of millets even won a Grammy Award.

Once considered inferior, millets are being touted as a powerhouse of health, economic, and environmental benefits. But the revolution isn’t just about the grain itself. Now the focus is shifting to taste, packaging, and convenience, leading to an explosion in millet entrepreneurship.

Last year, the central government upped the ante with a production-linked scheme for millets, with an outlay of Rs 800 crore, to encourage more ready-to-eat and ready-to-cook products. And Hyderabad has become a leading hub of this millet-makeover movement.

Driving it are passionate farming collectives, institutions like the Indian Institute of Millet Research (ICAR-IIMR)—which received funding last year to become a “centre of excellence” for R&D—and tenacious startups fuelled by faith in millets as much as by financials.

Sai Krishna’s Health Sutra is one such startup. An IIT Delhi graduate, he had dreams of launching a momo quick-service chain in the bustling streets of Hyderabad, until fate nudged him towards an education company. But this cushy job did not extinguish his entrepreneurial spirit. Around 2014, when Krishna was exploring food-related business ventures, inspiration came from an unlikely source—his father’s diabetes diagnosis.

“The doctor’s recommendation to include oats and quinoa into my father’s diet gave me a push to dig deep into millets,” he said.

But Krishna’s first attempt at taking millets mainstream as a convenience food— a jowar porridge mix—failed to take off in the market.

“Our main hurdle was first educating people about the porridge, then introducing the millets, and finally, preaching the health perks. It was quite the uphill battle,” he recalled.

Frankly, nobody cares about health. In India, taste is what you are up against when you are in the food business

-Raju Bhupati, founder, Troo Good

But Health Sutra didn’t give up. They focused on popular breakfast and snack options, creating millet alternatives that looked and tasted similar to the originals. Today, the brand offers 15 products, from breakfast cereals and dosa batter to biscuits and poha, available in close to 3,000 supermarkets in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Orders from across the country also come in via Amazon and Krishna said it has a strong customer base in the UAE.

Started with an investment of just Rs 5 lakh, Health Sutra today boasts an annual revenue of Rs 4 crore.

Like Krishna, other entrepreneurs, with an initial investment of just Rs 3-5 lakh, have spun their humble beginnings into gold, becoming a new breed of millet millionaires.

The ecosystem also includes ICAR-IIMR’s Nutrihub, a government-supported incubator for millet startups, and restaurants like Millet Marvels. Some farm-to-factory enterprises, like Vishala Reddy’s Millet Bank, not only sell FMCG products but also work with farmers and organise workshops to promote awareness.

“It’s like Test cricket,” Reddy said. “You have to be on the field, create awareness, build an industry, and maybe later you can make crores.”

Also Read: Is bajra the new wheat? How ICAR’s turning humble millet into versatile, ‘luxury’ ingredient

Taste, aspiration, price

In 2012, Raju Bhupati made a life-changing decision. He quit his lucrative tech sector job, surrendered his US green card, and returned to India, vowing to “stay till the end”.

Bhupati wanted to be closer to his mother and, in his own way, carry forward the legacy of his father, a homeopath who treated thousands without charge. This eventually drew him into the world of millets.

Launched in 2018, Bhupati’s company Troo Good started out with millet parathas and then branched out to chikkis and bars. It is now a top brand in this space, churning out roughly 2.5 million chikkis daily for a pan-India customer base. Its annual turnover is Rs 120 crore, according to Bhupati.

Over the past five years, Bhupati hasn’t just focused on profits. He’s established six factories across India, including one in Chhattisgarh’s Naxal-affected Bijapur, specifically to provide much-needed employment opportunities for local villagers.

“You can hear rifle sounds next to our factory but nothing holds us back. A source of income for these villagers is also essential,” he said.

On the marketing front, Bhupati avoids a heavy-handed approach to promoting millet health benefits. Instead, he aims to seamlessly integrate these ancient grains into everyday diets.

“Frankly, nobody cares about health. In India, taste is what you are up against when you are in the food business,” he said.

However, the brand does advertise the protein content of its millet chikkis.

“Protein is the cool thing now. It’s something young people can relate to,” Bhupati added.

Hitting the sweet spot in consumer perception is something all entrepreneurs are trying to do. Millets, once a common staple, are now seen as expensive and ‘elite’. The task at hand is to position them as premium treats while also making them attainable for a wide customer base.

“The biggest challenge is to make millets cool. It has to be made aspirational. The middle class are aspirational. They look up to elites and follow,” Krishna said.

The right price points also go a long way. A Troo Good millet bar packs 4 grams of protein for just Rs 10, compared to Rs 70 for a Max Protein Bar with 10 grams.

At a small tea shop in Hyderabad’s Madhapur district, a group of students enjoy their evening tea alongside a millet bar. It is part of Pawan Yadhavar’s daily routine.

“To be honest, I don’t know a thing about millets, but this chikki feels like those pricey protein bars. Can’t afford those every day,” Pawan said.

For Bhupati, the mission is accomplished.

Evangelical zeal

In a profit-driven world, some entrepreneurs are going beyond economics to evangelise about the power of millets.

In the cafeteria of Value Momentum, a software company in Hyderabad, around 40 employees slump in their seats, anticipating yet another dull presentation. They’re eager to get it over with.

Then, Vishala Reddy, the 45-year-old founder of Millet Bank, strides in and immediately injects energy into the atmosphere.

“Hands up if you’ve tried millets!” she urges the audience. Only two people raise their hands, while the others look bemused. Reddy is unfazed. Her mission, along with nutritionist Nida Fatima Hazari, is to deliver an educational hour, complete with a cooking session and pop-up snack stations.

“I was today years old when I learned about millets. I wouldn’t call it delicious but it’s not bad either,” said an employee later, spooning up the final nibbles of his sorghum salad.

Meanwhile, Reddy observed from a corner with a satisfied smile as the initially unenthused employees chatted about millets and ate their sorghum snack.

The workshop was part of Decode Millet, a 16-month project that aims to connect with a million corporate employees across 150 companies in eight cities, including Hyderabad, Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru.

This commercial aspect of millet cultivation will benefit the public, the industry, the farmer and is good for the environment as well

-Dr B Dayakar Rao, principal scientist, IIMR

A big gap needs filling, according to Reddy. In India’s 140-crore population, the number of people actively choosing millets is still negligible.

“Both the farmers who grow millets and the entrepreneurs who process them are doing society a favour, as the millet industry is still not financially beneficial,” she said.

Reddy focuses on corporate houses because they wield decision-making power, possess financial resources, embrace innovation, and show a growing interest in health-conscious choices.

“The corporate world’s sedentary lifestyle is fuelling health issues, making it a prime arena for spreading awareness,” she said.

India reigns supreme as the world’s top millet producer, contributing about 20 per cent of global production in 2023.

Women on the field

Many women in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are shouldering the millet movement, both silently on the fields and at the forefront.

Among them, Vishala Reddy is uniquely well-equipped in her mission to bridge the gap between corporations and the grassroots millet ecosystem. Her background straddles both worlds.

Raised in a farming family, Reddy intimately understands farmers’ daily struggles and all the ups and downs of millet cultivation. The first girl in her village to complete school and college, she pursued a successful career in business event management after obtaining her MBA from Osmania University. But all through her achievements and extensive travels across 25 countries, she yearned to give back to her community.

It’s like Test cricket. You have to be on the field, create awareness, build an industry, and maybe later you can make crores

-Vishala Reddy, founder, Millet Bank

“Being able to help the farmers through my startup filled that void,” she said.

Millet Bank, launched in 2021, is working to carry forward a “7,000-year-old millet farming legacy” by establishing market linkages between millet farmers and consumers.

Though Reddy started by supporting farmers within a 20-kilometre radius of her home, the venture has blossomed into a thriving Facebook community through which millet farmers can directly connect with startups and institutional buyers.

Millet Bank also sells a range of products, from sorghum noodles to ragi chocolate cookies to multi-millet upma mix. Armed with an equity grant of Rs 40 lakh from the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), the company recorded an annual turnover of Rs 6 crore last year, with Reddy targeting Rs 10 crore this financial year.

Meanwhile, across the border in Andhra Pradesh’s Vizianagaram district, the term “Millet Sister” is a badge of honour. It’s bestowed upon all women farmers associated with the Agro Millets Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO), led by CEO Saraswathi Malluvalasa.

Malluvalasa, 46, started Agro Millets FPO in 2016 with 200 female farmers and a community investment of Rs 3 lakh. Today, her organisation works with around 1,500 farmers. It not only provides employment to women, but also focuses on ramping up millet production. The FPO further acts as an aggregator and primary processor of millets, and markets finished products under the brand name Arogya Millets. Last month, Malluvalasa won the ‘Woman Exemplar Award’ of the Confederation of Indian Industry for her work with Millet Sisters.

For 43-year-old Padmavathi Annapurna Kalluri, a millet farmer and founder of Sri Haritha Agro Food Products Pvt Ltd, women are more aware and sensitive agriculturalists.

“Women have for long depended on their farms for income and food. They understand the surroundings better. They feel more responsible for the nutrition requirements of the family, about climate,” Kalluri said.

With an MBA degree and four years of experience in the IT sector under her belt, Annapurna has been running a millet farm in Andhra Pradesh’s Kolluru for the last 13 years. Her value-addition unit in Hyderabad produces millet-based snacks, instant mixes, and breakfast cereals under the brand name Avasya.

Also Read: Chicken feather plastics, temple flower foam—IIT Kanpur is changing India’s startup scene

‘Lost’ grain to ‘Shree Anna’

Millets have come full circle in India. For centuries, they formed the backbone of Indian diets, offering both nutrition and versatility with varieties like pleasantly nutty foxtail millets, slightly bitter jowar (sorghum), earthy ragi (finger millets), and toothsome bajra (pearl millets).

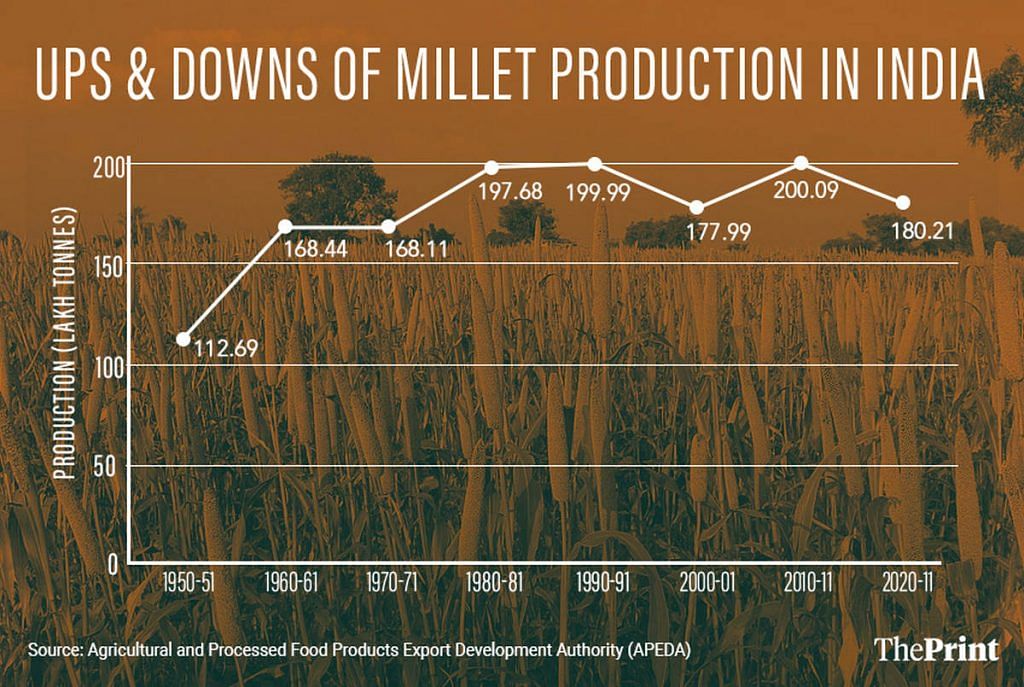

Then came the Green Revolution in the 1960s, which focused on boosting the production of rice and wheat to address food shortages. But millets were not a part of the equation and their consumption and production dwindled.

“The input subsidies as well as output incentive policies of the government led to the promotion of rice and wheat,” said Dr Dayakar Rao, principal scientist at the Indian Institute of Millet Research (IIMR).

But over the decades, cracks began to appear. The Green Revolution filled plates, but it also drained environmental resources and reduced crop diversity. With climate change anxieties and growing lifestyle diseases, the trend is being reversed and attention has shifted towards reviving these ‘lost’ grains. Millets, from a family of grasses, are easy to grow in dry, hot conditions, gluten-free, low in glycaemic index (GI), and packed with fibre and micronutrients.

The biggest challenge is to make millets cool. It has to be made aspirational. The middle class are aspirational. They look up to elites and follow

-Sai Krishna, founder, Health Sutra

With its millet push, the government is not doing anything new; it is merely going back to what Indian farmers were cultivating before the Green Revolution. Today, India reigns supreme as the world’s top millet producer, contributing about 20 per cent of global production in 2023. Rajasthan, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttarakhand together accounted for around 98 per cent of India’s millet production in 2023-24.

“Farmers will benefit more from millets due its input-output ratio in comparison to wheat and rice,” said , who comes from a farmer’s family in Andhra Pradesh’s Chittoor—a drought-prone belt that has a long history of growing ragi, jowar, samalu, and arikelu.

“I have grown up eating ragi mudde, a traditional dish in our village,” Reddy said.

Krishna is also optimistic, especially for South India, pointing out that awareness-building activities started earlier in the region.

“For instance, Hyderabad has ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics) which has been working on dry land crops, including millets, for over 50-55 years. We also have the Indian Institute of Millet Research,” he said. Similarly, there are also institutes specialising in millets in the agricultural universities of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

Scaling up production, however, is not a walk in the park. Farmers accustomed to growing millets for personal consumption are hesitant to take the leap to commercial production. Inconsistent demand, weak market linkages, and limited processing technology are all major roadblocks.

“Without demand, there was no incentive to develop processing technology for millets either,” said Dr Rao.

Efforts are underway to change this. Last March, PM Modi announced that IIMR would be designated as a “Global Centre of Excellence on Millets,” with a mandate to boost R&D in “Shree Anna”—the mother of all grains. A major piece in the puzzle is giving a shot in the arm to entrepreneurs working round the clock to make millets more palatable and sellable.

Nutrihub claims to have supported over 400 millet startups since 2016, providing them with technical support from IIMR scientists, access to funding, and marketing assistance.

Startups cooking up a storm

On the IIMR campus sits a neat, white, single-story building with a red sign identifying it as the ‘Nutri Cereals Innovation Centre’. This is Nutrihub, a Department of Science and Technology (DST)-supported incubator for millet startups.

It claims to have supported over 400 millet startups since 2016, providing them with technical support from IIMR scientists, access to funding, and marketing assistance.

Helmed by Dr Dayakar Rao, it functions rather like a college where startups enroll for a year.

The incubator operates on dual fronts. The first is a research centre where startups innovate with IIMR’s technology to develop various products from different millets. For instance, one startup is working on making noodles by mixing two millets, while another is creating macaroni using finger millet.

The second wing is a shared facility where emerging ventures can fulfill large orders of millet products without the upfront cost of equipment. This facility includes a primary processing line for cleaning, destoning, grading, dehulling, and separation of grains. Next to it is a milling line, with large orange and white machines that churn out flour, semolina/rawa, and more.

Whatever their specialisation, startups have the right tools handy—from a cold extruded line churning out vermicelli and pasta to a baking line for cookies, biscuits, and muffins. There are also dedicated set-ups for extruded snacks, health bars, and even crunchy murukku.

It’s currently incubating nearly two dozen startups, with names like Millet Marvels, Millet Mantra, and Millets & More.

“This commercial aspect of millet cultivation will benefit the public, the industry, the farmer and is good for the environment as well,” Rao said.

Comeback on the plate

A few months ago, IIMR came up with a clever strategy to make millets more palatable—developing a variety that looks just like rice. This speaks to the fact that getting Indians to look beyond their beloved rice and wheat is no easy feat.

For all the much-trumpeted health and environmental benefits of millets, it’s still rice and wheat that dominate household meals, supermarket shelves, and restaurant menus alike.

A demonetisation-like strategy won’t win over taste buds, but startups are all trying to find the best entry points.

For Krishna, it’s all about staging a takeover of breakfast.

“Looking at the stories of Kellogg’s and other brands, breakfast is the moment where habit change can happen in comparison to lunch or dinner,” he said.

Some restaurants are also doing their bit by serving a selection of millet items, while others are making it their identity.

Millet Marvels, the brainchild of cardiologist and actor Dr Bharath Reddy, is one example.

Launched in 2020, the restaurant has developed recipes like millet pani puri, chaat, and pav bhaji—all with the lofty goal of changing the way Indians eat.

Reddy claims that most customers become millet converts once they’ve had a few bites of the restaurant’s preparations, even if they were reluctant initially.

“Ninety-five per cent of people have gone back on their word and developed an appetite for millet dishes,” he said.

Whether the millet revolution will actually push rice and wheat to the edge of our plates remains to be seen, but evangelists and entrepreneurs are exploring every avenue possible.

After supermarkets, restaurants, and the corporate sector, the next target is schools.

Nutritionist Nida Fatima Hazari suggests taking a leaf from the aggressive marketing that Nestle’s Maggi did during its early days in India.

“They gave free Maggi packets to children during their school drive. The next thing we knew is that it became a popular snack among all age groups,” she said. “Making millets cool and popular among children will help the industry grow five times in the next 10 years.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Rather than selling it in the markets as food alongside wheat flour and rice, the idea of selling millets as product will take the long drawout path of first being an expensive elite food before it becomes part of the staple food, like all the ‘products’ that have come in the market