Kanpur: When disaster strikes, Alakh is almost always summoned—be it during the 2021 Chamoli floods or the Silkyara Bend–Barkot tunnel collapse. On 12 November, when a portion of the tunnel collapsed trapping 41 labourers, the indigenously developed drone flew through the debris that no human could enter. Its eyes ‘saw’ and captured the vital first information required to plan the 17-day rescue mission.

Alakh is a product of EndureAir, an IIT-Kanpur incubated startup that designs and manufactures unmanned aerial vehicles. Now, the team is developing a drone that can carry up to 20 kilograms of ‘cargo’ and deliver it to high-altitude army posts. EndureAir is one of more than 300 startups that have been birthed and incubated at IIT-Kanpur’s Startup Incubation and Innovation Centre (SIIC), which is changing the way we live.

From tracking fraudulent cryptocurrency transactions to creating biodegradable ‘plastics’ with bamboo and chicken feathers, and designing sunflower-inspired solar panels—the institute’s incubation cell is pushing startups to find science-based, sustainable solutions to national problems. While one startup is making vegan leather with discarded temple flowers, another is using nanotechnology to breathe new life into degrading soil.

Most entrepreneurs come to IIT-Kanpur with good ideas—what they lack, however, is the roadmap to turn those ideas into a business. Since launching SIIC in 2000, IIT-Kanpur has been on the frontline in the innovation race. The incubation centre is proving to be a catalyst for change—connecting entrepreneurs and scientists to funders and providing infrastructural support.

Apart from being one of the first incubators in Uttar Pradesh, IIT-Kanpur has two distinct advantages. The first is “massive” funding from corporations as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives.

“This year alone, we will be giving out Rs 15 crore from our CSR funding,” said professor Amitabha Bandyopadhyay, who is on the board of directors at SIIC.

At IIT Kanpur’s incubation and innovation cell, startups are tracking fraudulent cryptocurrency transactions, creating biodegradable ‘plastics’ with bamboo and chicken feathers, and designing sunflower-inspired solar panels. One startup is making vegan leather with discarded temple flowers; another is using nanotechnology to breathe new life into degrading soil.

The second advantage is that IIT Kanpur has its own investment corpus of Rs 50 crore. “This is important because we primarily promote hardware startups, which are yet to become popular among venture capitalists or angel investors,” Bandyopadhyay added.

And it was a national crisis that alerted the rest of the country to the institute’s potential.

“The real boost really happened during Covid. Our incubator delivered so many products one after the other that we became very prominent,” the professor said, referring to the ventilator project, which was developed and introduced in the market within 90 days. “Suddenly, the number of incubatees applying to our cell went through the roof,” Bandyopadhyay said.

The major challenge of being an incubator, he said, is that one does not really know what to prepare for. “If it is your own research lab, you know the research programme for the next 15-20 years. So you set up the equipment accordingly.”

The infrastructure of an incubator should cater to incubatees, but they will change every few years. This transience is what keeps the SIIC on its toes.

Also read: A genetic testing revolution is on. Indian patients lining up for answers to rare diseases

The value of discarded flowers

The journey of another startup, Phool, began on a cold winter Makar Sankranti morning eight years ago, when its founder and CEO Ankit Agarwal took a friend visiting from the Czech Republic to the ghats of the Ganga. The friend’s questions about why so much waste gets dumped into the holy waters got Agarwal thinking.

He arrived at a simple idea—collect the used flowers from temples and turn them into incense sticks. However, it was not easy convincing the priests. According to Hindu rituals, flowers offered to devotees have to be submerged in holy waters.

Agarwal’s team spent a lot of time convincing the temple priests, eventually succeeding in placing bins to store these flowers for the Phool team to collect them later.

Phool employed women from families engaged in manual scavenging—offering them a steady employment of dignity.

Today, hundreds of women in Uttar Pradesh’s villages are hand-rolling agarbattis (incense sticks) made from used flowers; one of Phool’s investors includes Alia Bhatt.

Over 300 startups have ‘graduated’ from IIT Kanpur’s SIIC, which currently incubates 163 companies.

But this was just the first step in Phool’s journey of exploring innovative solutions for organic waste. Nachiket Kuntla, an MTech from IIT Kanpur and the startup’s lead research scientist, recalls the team discovering a whitish mould in the pile of used flowers.

The team realised that fungal growth was turning used flowers into a lump that resembled thermocol. And thus was born Florafoam—an organic packaging material made from discarded flowers and agricultural waste. Kuntla’s is now conducting trials with some companies to replace packaging with ‘Florafoam’.

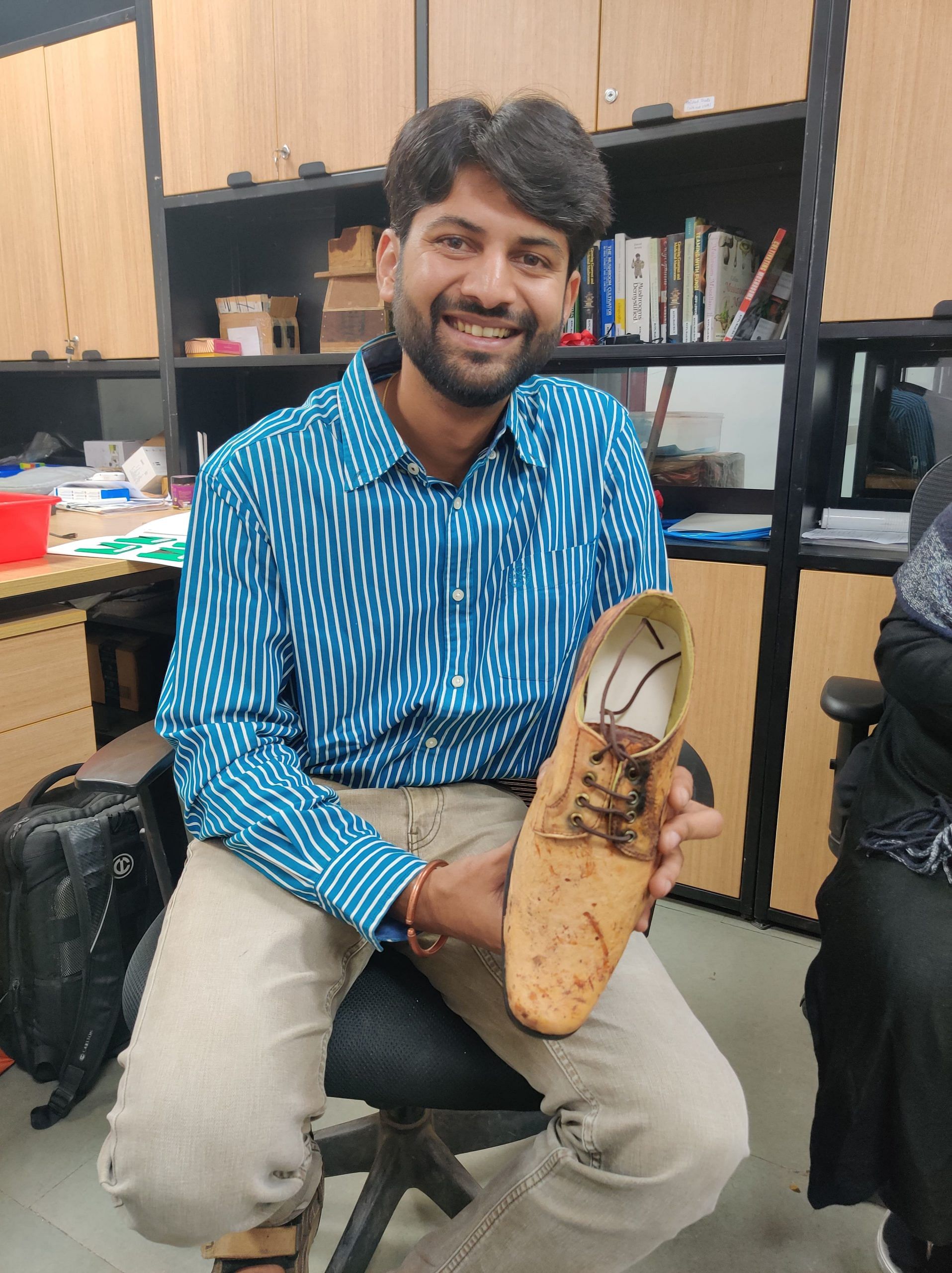

Their research has led to the development of vegan leather from biomass, and the company is now in talks with an international brand to explore developing products from this leather.

According to Agarwal, this would not have been possible without the help of SIIC. “We started with a room in the SIIC lab that didn’t even have shelves to keep chemicals. But within a couple of days, Professor Bandyopadhyay ensured that the room was converted into a workable lab,” Agarwal recalls.

Chicken feathers for plastic

This very room is now brewing another startup, NovoEarth, where Sarthak Gupta is trying to find a solution for phasing out single-use plastics. And he is doing this by tackling a major waste problem—chicken feathers.

“Chicken feathers are a menace for municipalities with poultry farms paying them to get rid of this waste,” said Gupta. But a keratin protein found in chicken feathers can be converted into compostable polymers, which can be used to develop products that can replace single-use plastics.

For Santosh Kumar, founder of Pacing Grass, the goal is the same but with different means. Kumar has converted bamboo fibre into a plastic-like composite that can be used to create microwave-friendly utensils, industrial machine parts, crates and much more.

Both NovoEarth’s and Pacing Grass’ products are available in the form of pellets, which can be utilised by the traditional plastic industry to replace their raw materials, eliminating the need for a complete overhaul of the entire production line for single-use plastics.

Also read: Forget diplomatic chill, Indian and Pakistani startups and talent are hooking up on the quiet

Sunflower? No, it’s a solar panel

About 4 km away from Kanpur’s industrial area in Panki, there’s a neighbourhood just off Kanpur Road, with lanes lined with unplastered brick houses. Among them, the Katiyar family’s home stands tall, distinguished by a unique feature. Unlike most rooftops adorned with lines of clothes hung out for drying, the Katiyars’ roof boasts a set of solar panels.

These solar panels are no ordinary ones. Equipped with ‘Solar Trackers’, the panels are programmed to automatically align themselves to face the sun. They increase the power generation potential of regular solar panels by 40 per cent. Designed by the IIT-incubated startup SunSync Technologies Pvt Ltd, the Solar Trackers draw inspiration from the behaviour of sunflowers. An algorithm, based on the GPS location of the panels, calculates the sun’s position in the sky.

According to Priya Katiyar, a family member, their electricity bill has gone down significantly. “But we are planning to increase the panels because it [the bill] has not yet gone to zero,” she said.

The Solar Trackers are the brainchild of Swaraj Patil, chief technology officer of SunSync Technologies and Rahul Gupta, a third-generation entrepreneur. The team is now planning to export the technology to other countries while establishing a market for Solar Trackers in India.

Also read: Shipping containers as office, 3D printed rocket engine—a Chennai startup is in a space race

Making soils yield better

When Akshay Srivastava travelled 450 km from his village in Gorakhpur to meet professors at IIT-Kanpur, security guards at the gate turned him away. But the engineer, hailing from a family of farmers, did not give up.

He had a solution to improve soil yield—a solution cheaper than organic fertilisers and an alternative to the chemical ones farmers depended on. While studying engineering at Madan Mohan Malaviya University of Technology in Gorakhpur, Srivastava realised that the required amount of chemical fertilisers had increased tenfold in the last decade for the same patch of land.

“We discovered that the microbes in the soil that break down these chemical fertilisers were decreasing,” he said.

The solution was organic fertiliser, but the existing ones in the market did not yield good results. Also, using organic fertilisers increased the investment, he added, which is why farmers turned to chemical fertilisers in the first place.

“We keep increasing our investment, but the yield keeps reducing,” he said. Srivastava wants to break this vicious cycle through LCB Fertilisers.

At the outset, LCB started isolating microbes from areas untouched by chemical fertilisers. “For three years, we worked with microbial combinations that were customised based on the nutrients a crop needs,” Srivastava explained. The team secured an internship opportunity at IIT-BHU, where they conducted some of their research work.

On 12 February 2020, Srivastava officially registered his company. “But then Covid happened.” As the country went into lockdown, all the team’s microbial cultures in the lab died. “About seven years of our work was wiped out. We were completely broke.”

With just about Rs 7,000 left in his pocket, he once again collected microbial samples from fields and developed fertilisers.

Their first large-scale order for 40 kg of fertiliser came from Kannauj. With very little money to spare, Srivastava loaded the bag of fertiliser onto a bus to Lucknow. He asked a friend there to unload it and then to put it on another bus to Kannauj.

“When you don’t have money, friends come to your help,” said Mukesh Singh Chauhan, LCB’s Chief Marketing Officer.

After every successful order, Srivastava would tag IIT Kanpur’s Amitabha Bandyopadhyay on X (formerly Twitter) until one day the professor finally reached out to them.

Today, his startup is further enhancing its products using nanotechnology.

Cybercriminals, watch out

The C3iHub at IIT-Kanpur, with its giant screens, resembles a room straight out of spy movies. Black screens line the walls, displaying numbers, pie charts, codes, and chemical plant layouts. Unlike the engineering and chemical labs in the institute, this hall is immaculate— perhaps because scientific paraphernalia like conical flasks, wires, or chemicals are irrelevant here.

The C3i lab is dedicated to research in the cyber world. From deciphering cryptocurrency transaction trails to securing the operation of industrial plants that could spell disaster if hacked, the lab is focussed on fortifying the virtual world.

Within this high-tech space, Deepesh Chaudhari, founder and CEO of Block Stash, is developing an analytic tool to investigate and monitor illicit activities related to cryptocurrencies.

“Currently, all investigations stop if fraud happens with cryptocurrencies. This is because most investigative agencies are not trained to deal with cryptocurrencies. Many do not even understand the concept.” explains Chaudhuri.

Unlike traditional financial fraud, where victims are typically the elderly who are less familiar with technology, those falling prey to cryptocurrency crimes are younger and highly educated. These people hesitate to report the crime.

Block Stash is collaborating with West Bengal and Odisha police to solve such crimes.

“At present, we can trace illegal transactions. Although we cannot always trace back to the user, we are at least able to identify and tag suspicious addresses associated with illicit accounts,” he said.

Unlike traditional financial fraud, where victims are typically the elderly who are less familiar with technology, those falling prey to cryptocurrency crimes are younger and highly educated. “This makes them hesitate to report the crime,” Chaudhari said.

He hopes that Block Stash will raise awareness about cryptocurrency crimes among users and law enforcement agencies in India.

Adarsh Kant’s Cyber3ra is also looking to secure cyberspace but has adopted a different approach. Cyber3ra offers a platform for an army of independent ethical hackers. Any company wishing to monitor its digital assets can sign up on this platform.

The team of ethical hackers systematically attempts to breach the listed systems, with those identifying and reporting vulnerabilities earning a ‘bounty’.

At present, over 300 startups have ‘graduated’ from SIIC, which currently incubates 163 companies. SIIC’s robust funding enables the promotion of hardware startups, an area yet to gain significant traction among venture capitalists or angel investors.

Ashish Gaikwad of Reflex Drive, which focuses on drone parts, highlights that India is a hub for software development but there is hardly any investment in hardware research due to its capital-intensive nature.

“But because we have our own investment corpus, we can plug in that critical lacuna. I think that more ambitious startups are now coming to IIT Kanpur. Many of them are at the national forefront,” said Bandyopadhyay.

Even at night, many labs at IIT Kanpur remain brightly lit, with teams tirelessly working on the next ‘big idea’. In one such workspace, dominated by a particle accelerator, Chirag Agarwal holds up a small hand-held device—a portable X-ray machine. With it, his startup, Lenek Technology, wants to revolutionise TB screening in India.

(Edited by Prashant)