When Shivam Bansal takes pictures of the night sky, he uses three filters, changing them one by one on his monochrome camera that captures a very specific colour wavelength. The filters help him click objects that are hundreds of millions of light-years away.

The 23-year-old MBA student from Agra is part of a niche band of astrophotographers in India who combine their passion for photography with their fascination for the universe. They are transfixed by the moon’s craters and shadows, the planets, and the Milky Way. They hunt distant galaxies and nebulae, record celestial events such as phases of Venus, and chase eclipses across the world. They innovate and help each other improve their art, spending money and hours on their passion of capturing the beauty of the night sky.

Once he gets his perfect shot, Bansal spends days processing the image on his computer, referencing scientific data to bring out the correct colour of the gases at the right intensity and brightness. The result is typically a brilliant explosion of one or two hues — an accurate representation of a nebula or a galaxy if we could see them with our eyes.

“Even the best camera cannot capture the stunning beauty of these distant objects and the night sky that our eyes can see. This is why we spend so much time, money, and effort to bring these objects to life, to replicate their real properties, and to show how the eyes would see them,” said Bansal, who has been at it since he was 16 years old.

Astrophotography can be an expensive hobby that requires telescopes, specialised cameras, filters, photo editing software and the time to travel to high altitudes or locations at least a hundred kilometres away from light pollution—with no market for photos. It’s only in the last few years—especially with astro tourism picking up in India—that the work of astrophotographers like Bansal has been receiving attention from an online community of stargazers. More and more people are dipping their toes, or rather their cameras, in the night sky.

For people starting out, astrophotography doesn’t have to be very expensive or require extensive travel. New entrants capture photos with their smartphones and telescopes, from small balconies in the middle of bustling cities.

In 2019, when Sona Shahani Shukla was observing the moon from the telescope on the balcony of her Delhi apartment, her then-13-year-old daughter put the mobile phone camera against the eyepiece. And Shukla took a picture.

“Suddenly, I could see more details on the screen than through my eyes,” she said. “My reaction was, ‘Oh my god, what have you shown me? There is so much to be done here’.”

Also read:

Chasing galaxies, eclipses

In India, typical destinations for astro-tourists and astrophotographers are in Himalayan towns of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Kashmir. The most popular destination is Ladakh’s Hanle.

Dorje Angchuk, engineer-in-charge at the Hanle Observatory, is a relatively new astrophotography convert but has become a prominent evangelist in the field.

“Experienced photographers taught me their game, and now, whenever visitors come, I am very happy to photograph planets and galaxies with them,” he said.

Angchuk is a prolific photographer and publishes his work on social media to popularise Hanle as an astro tourism and photography destination.

Other photographers have explored rural regions away from light pollution, especially in Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka.

Travel photographer Bharat Moro recommends against the Western Ghats, though. “There are pockets in [the] Western Ghats where you have a good view, but the mountains here obscure the skies from the narrow valleys.”

In 1972, more than 800 people, including scientists and one cat, sailed from New York on the 23,000-tonne luxury liner Olympia to a specific spot on the Atlantic Ocean in a bid to witness a total solar eclipse. When the event finally occurred, and everyone gazed up in the sky, the ship’s band played You Are My Sunshine, said a report in the Smithsonian Magazine.

Ajay Talwar, 58, doesn’t have an ocean liner at his disposal, but he is a dedicated ‘eclipse chaser’. Enthusiasts like him go by many names—umbraphiles, coronaphiles, eclipsoholics or ecliptomaniacs. He flies all over the world with his airline employee spouse and his family, chasing total solar eclipses.

“Eclipses take us to places we would otherwise never think of going to,” said Talwar, who shot his first total solar eclipse in Barkakana, near Ranchi, in 1995. He has since travelled to Argancy at the French-German border (1999), Antalya in Turkey (2006), Redfish Lake in US’ Idaho (2017), and Sirsa in Haryana (2020).

When he couldn’t photograph the Indian total eclipse of 2009 due to monsoons, he flew on a special flight commercially sold out to eclipse chasers, and photographed the dark sun. He has even shot the second occurrence of a rare phenomenon called ‘tutulemma’ – an ‘analemma’ that includes a solar eclipse. An analemma is a figure-eight-shaped diagram that documents the sun’s journey in the sky, and is typically constructed by clicking photos of the sun from a fixed position and location every day at the same time over the course of a year.

Talwar is currently in the US on a recon mission ahead of the annular eclipse on 14 October at Crater Lake, Oregon.

Total solar eclipses are photography magnets and most of the community is already planning for the upcoming decade — the US in 2024, Iceland in 2026, Egypt in 2027, Australia in 2028, and Kashmir in 2034.

Eclipse chasers hunt for the path of totality—the zone where the moon’s shadow covers the sun. The sun’s rays are blocked, and temperatures drop as darkness unfolds in this shadow zone for a few seconds.

Celestial events such as eclipses are transient; when a good shot is missed, photographers must wait another few years and travel to the next location. When Bansal was in the Australian outback for the total solar eclipse earlier this year, he practised his shooting routine for the 60-second window multiple times the night before.

Also read: Astro labs are the new wave in UP village schools. Delhi man revolutionising physics

Community and the deep sky

Civil engineer Deval Singh, 33, doesn’t chase eclipses—not yet. He simply stepped out of his house in Amarkantak in Madhya Pradesh and looked up. Singh, who works in the state’s urban development department, became interested in astrophotography while locked up at home during the Covid-19 pandemic. He spent time learning the craft through YouTube videos and other photographers.

Around five months ago, he joined some astrophotographer groups on WhatsApp. They helped him refine his techniques with the beginner equipment he had invested in.

“I still consider myself a beginner. I just began seriously doing this about six months ago. I am so grateful to the community,” he said.

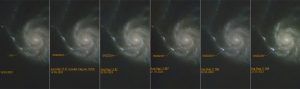

He decided to practise his skills on one particular celestial object. On 18 May, he turned his gaze to one of the most popular amateur astronomy targets, Messier 101, also known as the Pinwheel Galaxy. Over two nights, Singh took wide images of the galaxy from dusk till midnight.

His spectacular photos showed the galaxy in its full pinwheel glory, with millions of glistening stars against a pitch-black background. And on 19 May, news broke that a supernova had been detected the previous day in the Pinwheel Galaxy. Singh had serendipitously photographed the supernova without even realising it.

“This experience has been unbelievable, I was not expecting this at all, ” he said.

Like Singh, everyone in the community learns from each other on WhatsApp and Facebook groups, and many submit their photos to Nihal Amin’s Instagram handle, AstrophotographyIndia. With over 10,000 followers, it is the most popular online page for Indian astrophotography.

Gurugram-based management consultant Amin, 27, has been photographing the skies since 2014. In 2019, he launched his page to popularise astrophotography in India. Photographers submit scores of images to him, which he posts on his handle every day.

“When we began, there were just two or three images that were coming in. But since Covid, we have been getting tens of submissions a day, and the quality of these pictures is drastically climbing,” he said.

These photos are not for research, explains Amin, even though scientific photography is done by professionals and space missions such as the Hubble Space Telescope.

Landscape astrophotography is the most popular choice. “It requires being in a location with available, wide landscape or even a cityscape, with a dark cloudless sky in the background,” explained Amin.

Hobbyists graduate to deep sky photography when they want to start investing in more specialised equipment, such as powerful telescopes and photo filters like Bansal’s, which provide scientific data to accentuate the images. Their photos are colour-processed close-ups of distant objects, nebulae or galaxies, and the equipment includes several sophisticated accessories.

But the secret behind stunning photos of the deep sky isn’t in expensive equipment. Photographers experiment with the same target for days, if not weeks, with minor variations in settings and hundreds of hours of exposure for a single shot.

And then there are the innovators and discoverers—those who experiment with photography to bring out fantastic imagery, capture an event like a meteor impact on the moon, or discover a supernova the way Singh did. For that, access to dark skies is a must.

Also read: Humayun was obsessed with astronomy, wanted a utopian society favoured by heavens

Costs, locations, entry barriers

The universe literally compels photographers like Talwar, Amin and Bansal to spend their savings on capturing single moments in time. Serious astrophotography requires telescopes suited to the style of visualisation (wide swathes of the sky or zoomed-in features on a planet), cameras to suit different needs (monochromatic for narrowband and thermal regulation for high altitude exposure), as well as mounts and trackers (to compensate for the rotation of the earth). The equipment must be extremely sturdy to withstand extreme variations in temperature, strong winds, and long periods of daily exposure to the elements.

Initial costs can run from anywhere between Rs 3-10 lakh over two years for all-rounded basic equipment because almost everyone imports them. There is also the customs fees, every astrophotographer’s biggest nemesis.

Bansal has oxygen, hydrogen, and sulphur filters, which he uses for narrowband imaging, a relatively new technique. Such filters allow just about six nanometers-wide wavelengths of light and can filter in oxygen (blue light), hydrogen (red), and sulphur (green), as well as helium and nitrogen. Each filter takes different coloured images, which are all then combined for the final result.

Most astrophotographers save for months, if not years, to buy a new piece of equipment.

“Most of my salary goes into buying equipment,” said Singh.

It takes multiple photographing sessions to get the hang of camera and telescope settings, with a considerable amount of time going into adjusting exposure. Heavy mounts and sophisticated telescopes take notoriously long to get comfortable with. Local weather plays a big role, with rains or even a small cloud ruining a night. And if the skies are clear, the weather will likely be extremely cold and uncomfortable. Then there is post-processing, which takes days, weeks, and sometimes months.

“Half of astrophotography is processing,” laughed Bansal. He, Amin, and a group of fellow astrophotographers captured pictures of the sky in Spiti and Kaza in Himachal Pradesh last year, and spent nearly six months processing and developing photos of colourful bursts of nebulae, faraway galaxies, and even shadows cast by the dazzlingly bright Milky Way.

There is no financial incentive for these photographers.

“A couple of magazines have purchased my pictures, but the amount I got, on rare occasions, was just a pittance,” said Talwar. He learned this early, and since 2010, has been conducting workshops to teach astrophotography to enthusiasts. He’s also branched out to building and selling telescopes.

But serious astrophotographers insist that lack of access to dark skies and expensive equipment need not deter new entrants.

Ever since her serendipitous first photograph in 2019, Sona Shahani Shukla has been hooked. She started taking photos and videos of planets, learned how to process and stack them, and worked with her iPhone XS for a year before switching to a DSLR. Shukla’s early images were all of Venus, Mars, and the moon, and she has since imaged all planets and multiple distant moons.

“I live in Delhi, and right across my balcony are two large LED streetlights. Thankfully, for planetary photography, light pollution does not matter too much because you have very short exposures,” she said.

In smaller towns, where dark skies are easily accessible, people have to simply step outside, said Singh, whose pre-imaging of the supernova made him a local celebrity.

“My town [Amarkantak in Madhya Pradesh] is mostly known for religious pilgrimages, and the infrastructure and culture around the temple and religion are well in place. This could also be adopted to encourage interest in astronomy and STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] under the brilliant night sky,” he said.

Shukla encourages everyone to try out photographing the stars or at least looking through a telescope. Telescopes are also often rented by beginners, and there is plenty of free software available for processing astro images.

“Imagine being able to look at a planet-wide dust storm or the largest volcano in the solar system on Mars, and then being able to take pictures of that from your balcony. How cool is that!”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)