Bijnor: The Faridpur Kazi school in Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district has become the talk of the town. Its fame is now spreading to neighbouring villages. In this government school, students observe stars during the day — in the school’s very own astronomy lab that brings science to life.

The school itself doesn’t look too different from its surroundings. Its sandy ground radiates the blistering summer heat back and its sharply built boxy rooms blend into the yellow landscape.

All but one room.

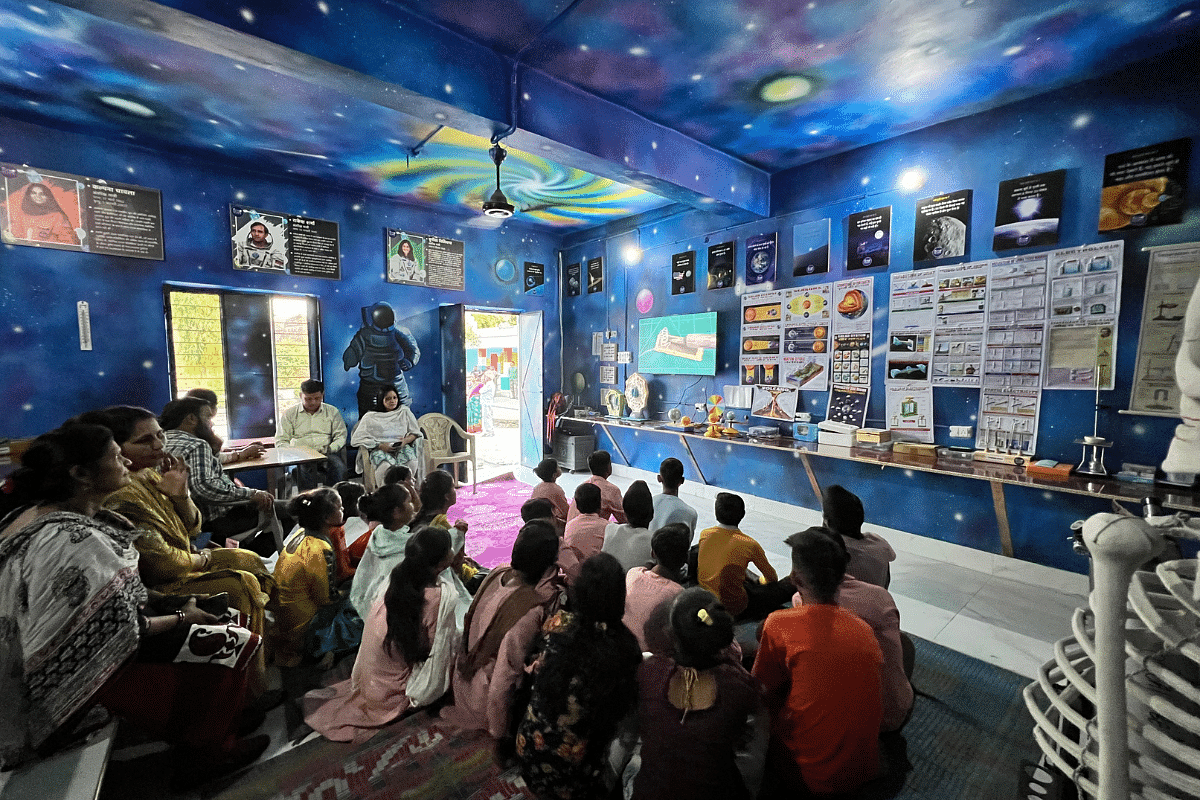

Bursting into view a few feet into the school ground is a bluish-purple-coloured square room that catches one’s eye. ‘Astronomy Lab’ is written on it in vivid lettering.

Its facade is covered with colourful drawings of planets, asteroids, and spaceships — with an ‘education’ inlay containing diagrams of test tubes, microscopes, telescopes, human anatomy, and other science-related ideas. Inside the astro lab, they all come to life—with experiments, images of space missions, star charts, panels of the Solar System, 3D-printed posters of planet interiors, virtual reality goggles, and a telescope.

The laboratory was built by 23-year-old Aryan Mishra, a Delhi-based astronomer and entrepreneur who founded Spark Astronomy in 2018 and now builds labs through his next venture Astroscape. The Narendra Modi government collaborated with the startup in 2019 to build more labs in villages across India. The son of a newspaper vendor, Aryan has built more than 300 such learning centres in schools till now. He has trained teachers and educators in every school with a lab.

In the last eight months, Astroscape has built 110 labs in Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Haryana, and Assam. Mishra is starting in Bihar next.

“The skies are accessible to everyone, we just need to know how to look at them,” says Mishra, who builds his own telescopes. “I am very passionate about bringing astronomy to every kid in India. Imagine the kind of STEM futures rural children would go on to have when they grow up looking through telescopes and reading the skies.”

At the Faridpur Kazi school, Aryan is a hero. As soon as he enters the lab, he is greeted with a burst of excited voices. Young students in pink uniforms promptly gather around him, chattering in rapid Hindi and firing remarks and questions: “How do I use this star chart?” “Can you check my notes?”

Two teachers wait patiently and approach him a few minutes later; they have been having trouble moving the eye-piece in the focuser on their telescope.

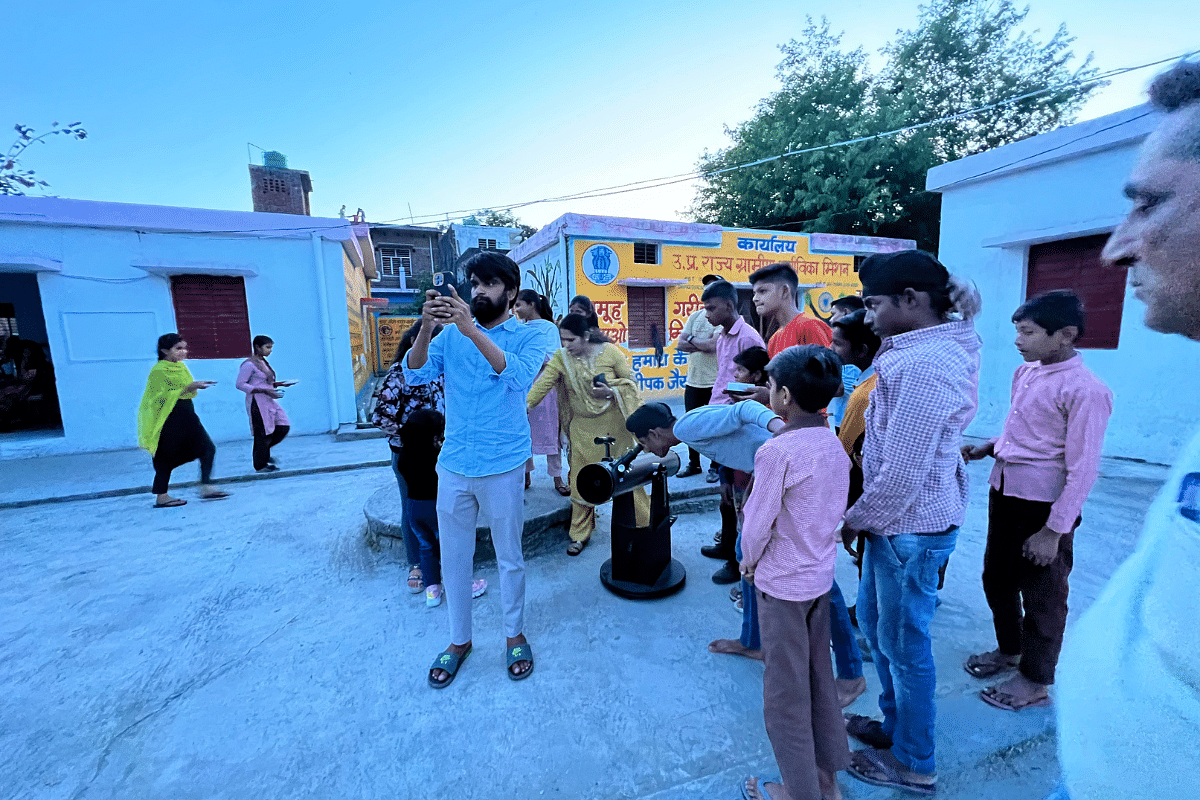

Behind them, in the corner of the room, sits a six-inch Dobsonian telescope, which students take out to observe the sun, active sunspots, and the surface of the moon. For these children in Bijnor, astronomy and physics have never been more exciting.

“The children are dying to get into the lab every day,” says a thrilled science teacher Naheed Abbas. “In the last few months, since the lab was set up, we have also seen great improvement in academic performance because children are now able to visualise and understand scientific concepts.”

Also read: SM Chitre, Stalwart Astrophysicist Who Once Shared Office With Stephen Hawking, Dies At 84

A galaxy in a room

If the outside of the lab is vivid and colourful, the inside is a kaleidoscope. Walls and ceilings are one large night sky showing neon patterns of galaxies and swirls. An entire wall is dedicated to explaining the Solar System — the eight planets, sun, moon, asteroids, and NASA missions to discover the final frontier. On display are some of the newest, highest-resolution images from the missions, sourced from NASA and other organisations. High up on the walls are giant posters of astronauts Rakesh Sharma, Kalpana Chawla, and Sunita Williams with brief biographies in Hindi.

There’s also a giant planisphere or star chart, which identifies stars and constellations in the night sky on any day of the year, and panels with augmented reality badges to understand the Solar System. A 50-inch plasma TV that plays science videos in Hindi from YouTube is part of the array of learning tools on display.

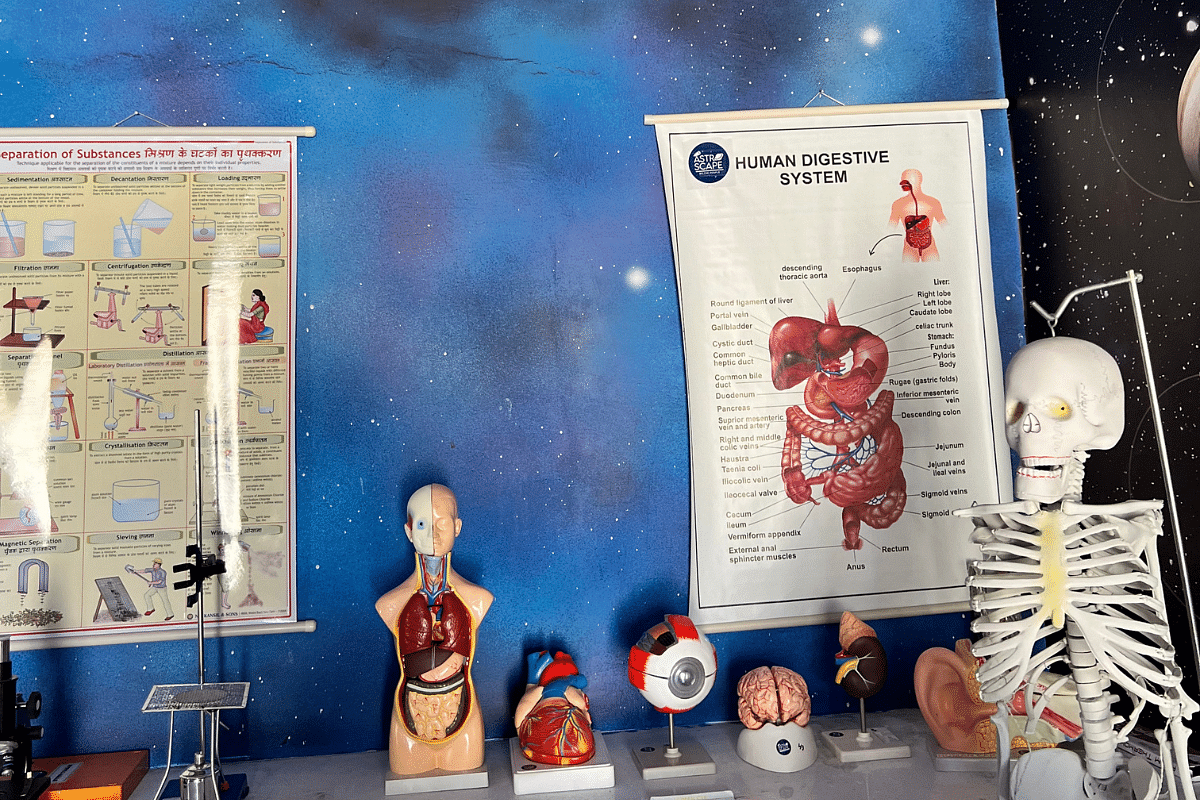

A waist-high platform runs along two walls, on which models, equipment, and experimental apparatus are kept.

“These three models demonstrate Newton’s three laws of motion,” says Class V student Adiba. She then goes on to explain inertia, show how acceleration impacts force, and deconstruct the mechanism behind the famous Newton Cradle, which demonstrates Newton’s third law.

Further down the room are anatomical models of the human body, a skeleton, more experiments, and a microscope with several prepared slides.

A separate group of students demonstrate solar cell experiments using a kit containing various circuits. They take the kit outside into the sun and connect the circuits to show how the solar cell converts energy into sound, electricity, light and other forms.

Also read: Humayun was obsessed with astronomy, wanted a utopian society favoured by heavens

Ramping up excitement

Bijnor’s chief development officer (CDO) Purna Borah is thrilled with the positive response from educators, which aligns with his objective to promote science education and increase school enrollment rates.

“These labs are getting absolutely fantastic results. They have been so promising that we are always trying to get new labs built,” he says. As many as 28 schools in Bijnor have worked with Aryan and Borah to set up labs on their premises.

There’s a similar sense of wonder and excitement among students in the Faisla Parmanand school, which is also in the Bijnor district. Here, a Class VI student took an intricate giant model of the human eye and pointed out the cornea, retina, optic nerve, and what these parts do. A Class III student with her could identify the skull, ribcage, and location of the heart on a skeleton.

The teachers are delighted to witness the growing enthusiasm and interest among their students.

“We have students who come and ask us about brand new concepts,” says science teacher Naseem Nazaqat. “They have started to actually understand scientific concepts instead of learning by rote.”

Aryan tapped into his deep-seated love for astronomy when he discovered an asteroid in a citizen science project at 14.

“I was suddenly invited to give talks in schools and colleges regularly,” says the self-taught astronomy enthusiast. “But I quickly realised I was way more enthusiastic about getting people interested in astronomy and appreciate it.”

Four years after discovering the asteroid, Aryan started wanting to build a platform for space enthusiasts and to develop affordable telescopes. He then expanded his efforts to establish astronomy labs and partnered with the office of then-Principal Scientific Advisor (PSA), K VijayRaghavan, to construct them in government schools.

“When I saw images of a lab he had built, I was stunned,” says Shailja Gupta, senior advisor at the PSA’s office. “After the first three government school labs in Jammu and Kashmir, I wanted to see these interactive labs in 500 Navodaya Vidyalayas.”

However, procuring funding for the Ministry of Education projects required going through the slow, bureaucratic system of tendering.

“The vagaries of the procurement system disallowed funding of 500 labs,” explains Gupta with a hint of sadness. “The system should really find ways to support smaller players who are innovative and cater to the needs of the Indian education system.”

Today, Astroscape works directly with gram panchayats all over the country. He built 220 labs in 18 states through Spark Astronomy (with which he parted ways in July 2022) and 110 labs through Astroscape.

The labs cost approximately Rs 2.5 lakh to build, which follows maintenance and training costs. They are funded at the district level through gram panchayats, with involvement from the district magistrate (DM) and especially the chief development officer (CDO) for overseeing its execution.

Aryan says that most bureaucrats he has worked with have been very forthcoming and cooperative.

“Bureaucrats are the ones who get things done at grassroots level. I often say that if politicians are kings, our country’s bureaucrats are the kingmakers,” he says.

Both teachers as well as gram panchayats have shown tremendous interest in his vision. According to the CDO and school teachers, the labs are in demand in rural schools across India, carried on by word of mouth within the vine of the rural government school network and education administrators.

“I have never had to pitch building the lab to a school,” he says. “Each time, educators have shown a lot of interest and wanted to work together to build them for students, which we were able to do.”

Also read: Vikram Sarabhai, the father of Indian space programme who was also a connoisseur of arts

Beyond the classroom

Aryan’s astronomy labs are designed to be run in perpetuity by teachers and students.

The wallpaper used for the lab is waterproof and fireproof. The lab itself does not contain anything too delicate to be accessible — and dangerous — to the youngest of students, and kids from grades I to VIII use them.

Aryan says he hopes to involve corporate houses and knowledge partners to take over building labs in the future.

Students treat the lab like a precious treasure and say the deep and complete understanding of the models makes them want to preserve it for future students.

Villages with even a single lab have also seen increased enrolment in schools overall, a trend that CDO Borah has also observed.

“The number of students in each class feels like it is increasing steadily,” says Naresh Kumar, a teacher at Tanda MaiDas secondary school. “We have already seen higher admissions in every class this year due to the attraction of the lab.”

Both block educator Preeti Pal and Borah say the initiative has helped involve parents as well. “Through this kind of engagement, parents are invested in seeing their kids in school. We are ready to immediately build more labs if funding is approved,” says Borah.

According to Pal and other district officials involved in the project, more parents in villages want to send their kids to school now. “Admission numbers are going up,” Pal adds.

Aryan’s vision for science education is not limited to classrooms. Astronomy has become a community affair of sorts in these parts, with active outreach by village residents to invite outsiders for the experience. Many villages in Bijnor have signboards welcoming people to the labs.

Just outside the lab at Tatarpur Lalu school, adults and children congregate for a khagol ratri to watch the rising full moon at the horizon through the telescope—everyone is discovering their inner scientist.

This article is the first in the Science and Community series.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)