Mumbai: The mustard fields are still yellow and green, but secrets coil like serpents under the swaying stalks. The baujis and beejis are still beaming, but what are they hiding? From Kohrra and CAT to Tabbar, Punjabi stories are taking over screens, replacing rose-tinted Yash Chopra fantasies with gritty, unapologetic realism. And a new crop of Punjabi actors is breaking down celluloid cliches, from the sunny Sikh to the village belle, one role at a time.

This latest wave of Punjabi content, be it on OTT or Bollywood, delves into the murkiest depths of the state—from militancy in the early ’90s to police corruption and the shadowy dynamics of the music industry. Drugs, caste, gun violence, sex, nothing is off-limits. The protagonists only come in shades of grey, and actors from Punjab are bringing them to life.

Even Bollywood filmmakers, traditionally wedded to stereotyped sarson da saag-makke di roti portrayals of Punjab, seem to be stepping up their game. Imtiaz Ali’s upcoming Netflix film Chamkila, starring Diljit Dosanjh as the slain singer Amar Singh Chamkila and Parineeti Chopra as his wife Amarjot, is set to release in 2024. Shah Rukh Khan’s Dunki, named after the illegal method of migrating abroad, is slated to hit screens on 21 December.

“Every actor in Punjab turned up to audition for Dunki,” said Bhawsheel Singh, known for his roles in Kesari (2019) and Udta Punjab (2016).

But the real action is on OTT with a slew of shows that are made in Punjab, about Punjab, but for an all-India audience, such as Netflix’s thrillers CAT (2022) and Kohrra (2023) and Sony Liv’s Tabbar (2021) and Chamak (2023).

These shows have been a launchpad for several Punjabi actors hungry for their breakout roles, like Suvinder Vicky, who spent two decades on the sidelines before nabbing the role of the compassionate but complicated policeman Balbir in Kohrra.

You cannot run a household with money earned from just theatre. You have to look for other acting jobs too, like ads or films. OTTs have helped a lot of actors

Suvinder Vicky, actor

For Punjabi talents from the state and beyond, it is a new era. No longer do they need to shed their turbans or take Hindi diction lessons to land a role. It’s their distinctive Punjabi characteristics that are getting them noticed. Even language is no barrier.

These shows seamlessly transition between Punjabi and Hindi, with subtitles and dubbing ensuring everyone can follow, noted Ajitpal Singh, director of Tabbar. “When we were auditioning for Tabbar, I was blown away by the local talent,” he added. The tide has turned, and now everyone is heading to Punjab.

Also Read: Goodbye Dabangg & Singham-style cops. Kathal & Kohrra’s gritty, grimy OTT police are here

Punjabi X factor

Chandigarh-born Wamiqa Gabbi ruled the OTT landscape in 2023, dazzling audiences as the iridescent Niloufer in Vikramaditya Motwane’s Jubilee and as the sharp yet endearing detective Charlie in Vishal Bharadwaj’s Charlie Chopra and the Mystery of Solang Valley.

And the attribute that clinched Gabbi the role of Charlie was her quintessential ‘Punjabiness’.

“When she talks in Punjabi, her whole demeanour changes. That is how I decided we needed Charlie to speak in Punjabi when she breaks the fourth wall (speaks directly to the audience) in the show,” Bhardwaj said in an interview with ThePrint.

In Godha (2017), too, Gabbi played a central Punjabi character— a wrestler who goes to Kerala but consistently speaks in her mother tongue. This role, too, showcased Punjabiness in a way that defied cultural stereotypes and contextual tropes.

But the path to genuine representation has not been a cakewalk.

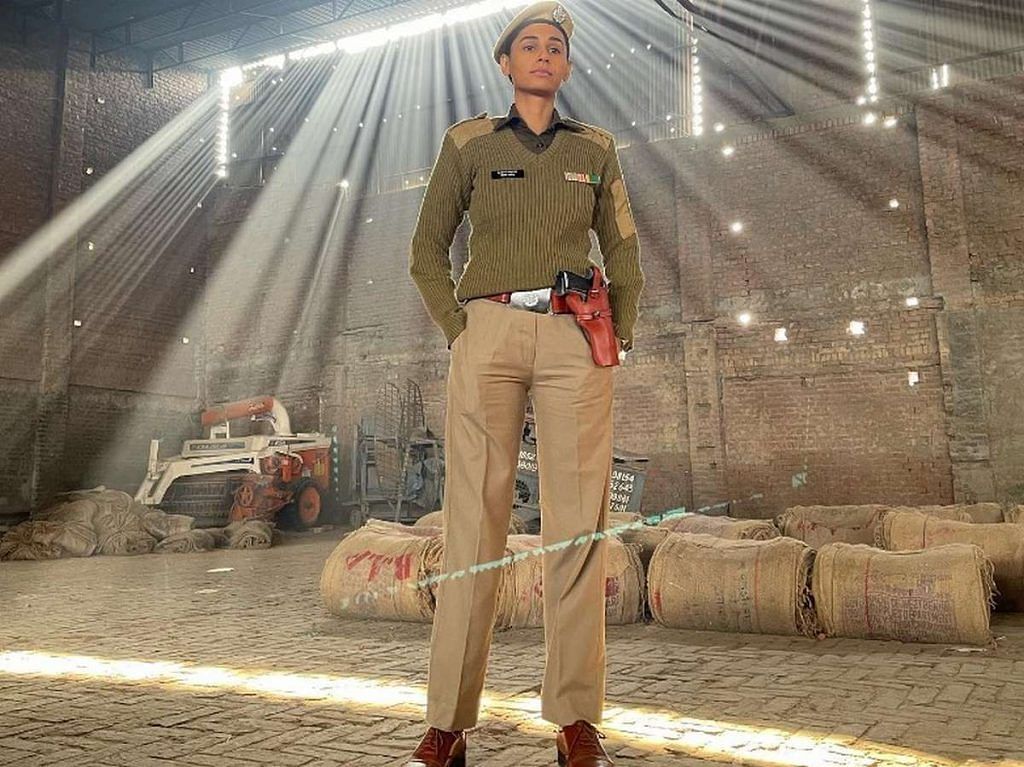

“I was asked to change my name many times while I was giving auditions in the beginning because it sounded too Punjabi, and I was told that it would hamper my career growth,” said Hasleen Kaur, a former Miss India who played the cop Babita in CAT and Ranbir Kapoor’s sister in Tu Jhoothi Main Makkar (2023). Kaur refused to change her name, but her story is a testimonial to how stereotypes spill over into the casting process too.

For actor Barun Sobti, a Delhi-bred Punjabi, Garundi in Kohrra was exactly the kind of role he wanted to sink his teeth into.

“I was hungrily looking for scripts like Kohrra. It’s about the complexity of relationships and Punjab, the colourful state that it is. There was no reason for me to say no to it,” said Sobti, who first shed his romantic hero persona from shows like Iss Pyaar Ko Kyaa Naam Du (2011-12) in the serial killer drama Asur (2020).

I was asked to change my name many times while I was giving auditions in the beginning because it sounded too Punjabi, and I was told that it would hamper my career growth

– Hasleen Kaur, actor

In Kohrra, Sobti stepped into the shoes of a young assistant sub-inspector caught between the guilt of an affair with his sister-in-law and the grind of police work. Garundi has a mean streak, using his fists and cuss words with abandon, but he is also emotionally untethered and desperate for marriage. Garundi strikes a chord because he is a young Punjabi who is nothing like the wholesome lassi-drinking, maa da laadla archetype.

Born and brought up in West Delhi, often memed for its very Punjabi nature, Sobti has never been “fooled” by the typical depiction of Punjabis as jolly, happy-go-lucky people. “Kohrra is an extension of a Punjabi family. Everyone is showing you the gold and cars, and that everything is fine. No one is telling you that everything is screwed up in Punjab, like in most other places. That is a very Punjabi way of showing off,” he said.

Thanks to the OTT boom, a thriving mainstream acting career no longer demands a move to Mumbai. Mumbai is also coming to Punjab.

Punjab fantasies & turban trials

Some of the biggest film producers in Bollywood and TV trace their roots to Punjab, but the state and its people have been woefully misrepresented, underrepresented, and stereotyped, according to director Ajitpal Singh.

“I think it comes from a place of trauma, especially post-Partition, and wanting to hold on to the nostalgia of what it was,” he said.

Set in the 1940s, Prime’s Jubilee touches upon the beginnings of the Punjabi influence in the Hindi film industry, albeit tangentially and in a highly dramatised way. The series follows Jay Khanna (Sidhant Gupta), who arrives in Mumbai after Partition with dreams of becoming a filmmaker. He faces numerous trials, machinations by his studio financier, and heartbreak on his path to success.

But the undisputed harbinger of Punjabiness in Bollywood was Yash Chopra, who made nodding mustard fields, fluttering dupattas, and NRI returnees mainstays of many films. Both nostalgic and over-the-top, his version of Punjab was an instant hit.

“Yash sahab brought in the medley, the fusion of Punjabi folk songs with Hindi lyrics, and it captured everyone,” said Rohit Jugraj, the creator of Chamak.

Chopra, a Hindu Punjabi born in Lahore, remained steadfast in his love for all things Punjabi, through his movies. His film Veer Zara (2004) changed the commercial landscape of Chandigarh. “He set the ball rolling for shootings in Chandigarh and inspired others to come here,” said Vivek Atray, former UT director (tourism).

However, another Punjab-inspired Bollywood tradition fuelled open prejudice.

If America had blackface performances, where White actors darkened their faces for slapstick Black roles, non-Sikh Indian actors donned turbans to play the ‘funny’ Sikh character. Actors from Johnny Lever to Anil Kapoor and Anupam Kher wore a pagdi for comedic effect. This impacted not just representation but opportunities for Sikh actors.

“Of course, non-sardar actors can play sardars. But why not give a chance to sardar actors, instead of getting someone to exaggerate as one?” said Hasleen Kaur.

Manjot Singh, who played Lavinder in Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! and Lali in the Fukrey film franchise, has claimed he was denied roles because of his Sikh identity.

“I was rejected because I was a sardar. It is believed that if one wears a turban, one can’t do serious stuff on screen—be it action or drama. I feel extremely hurt as there is a perception that those who wear a turban can only make people laugh,” he said in an interview. Bhawsheel Singh decided to stop wearing a turban in the hopes of getting better, non-stereotypical roles.

The Sikh lead roles that did surface were snatched up by other actors. For instance, Ajay Devgn, Farhan Akhtar, Salman Khan, and Akshay Kumar have all donned the pagdi as leads in Son of Sardaar (2012), Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2014), Heroes (2008), and Singh is Kinng (2008), respectively. Whether they did justice is open to debate. For Kaur, Amitabh Bachchan in Veer Zara (2008) came the closest to embodying a sardar from a village in Punjab with his diction, accent, and body language.

While not every actor portraying Punjabi characters in OTT shows comes from the state, there is a shared commitment to authenticity. Isha Talwar, who has spent most of her life in Mumbai, camped out in the small town of Moga to get into the skin of her character in Chamak. “It was like going back to my roots. At home, we don’t speak in Punjabi, and I had missed out on a lot. I learned to play the dhol, and to speak a certain way,” she said. Randeep Hooda in CAT reportedly took pains to converse with the entire cast and crew in only Punjabi for his power-packed performance.

But such dedication has typically been rare, and the detailing has often fallen short.

“While shooting for Kesari, I realised filmmakers do not even hire professional turban-tiers from Punjab, and it messes up the way it’s actually tied,” said Paramvir Singh Cheema, a lead actor in both Tabbar and Chamak.

Yet, with OTT platforms smashing language barriers and captivating global audiences, there’s a shift. Work opportunities are on the rise, renewing hope that stereotypes can indeed be dismantled through shows that rewrite the script about Punjab.

If America had blackface performances, where White actors darkened their faces for slapstick Black roles, non-Sikh Indian actors donned turbans to play the ‘funny’ Sikh character.

Reimagining a ‘black period’

Shows like CAT, Chamak, and Tabbar rip away Punjab’s vibrant façade and take an unflinching look at the lingering wounds of militancy, caste, drugs, and police brutality through their gripping stories.

CAT, an intense eight-episode series, shot in 80 locations across Punjab, delves into the militancy era as well as the contemporary drug epidemic. The story follows Gurnam Singh (Randeep Hooda), a former ‘cat’ enlisted by the Punjab police to spy on militants. He becomes an informant again to save his brother from drugs and infiltrates a powerful politician’s ring. The saga explores the intertwined nexus of drugs, politics, and police, all set against the backdrop of Punjab’s history.

“The Punjab police under IPS officer KPS Gill got unlimited power during the troubled times of insurgency, and they abused that power. That memory is very strong among the people who continue living in the state, and even among those who left it,” said Ajitpal Singh. CAT looks at the extrajudicial killings and human rights violations that prevailed in the era.

The flashy cars, the gun violence, and the women in music videos are all products of the brutal police crackdown that happened in the ’80s and ’90s

-Ajitpal Singh, director of Tabbar

“Though CAT is a work of pure fiction, it is inspired by what we saw and heard during that period. It is the story of the people we know, what they went through during the black period in Punjab,” said Balwinder Singh Janjua, director and co-writer of the show, in an interview.

According to Ajitpal Singh, the past informs the present, including the guns-and-gangs culture that saw singer Sidhu Moosewala being gunned down after a car chase and shootout in Mansa.

“The flashy cars, the gun violence, and the women in music videos are all products of the brutal police crackdown that happened in the ’80s and ’90s. The men were helpless then, but they are almost overcompensating now,” he added.

Moosewala’s killing triggered a collective re-evaluation beyond Punjab’s typical “happy vibe”, Bhawsheel Singh pointed out.

Also Read: YouTube favourite to OTT darling—TVF’s success has even Bollywood calling

Caste & family dynamics

Moosewala’s death isn’t the sole instance of murder entwined with music in Punjab.

Rohit Jugraj’s Chamak delves into the underbelly of Punjabi music, fictionalising the story of folk singers Chamkila and his wife Amarjot, both shot dead by unidentified shooters right after a performance on 8 March 1988. The unsolved case has given rise to many conspiracy theories, including that of a possible honour killing, because Amarjot belonged to an upper caste.

In Chamak, the murdered couple’s son Kulvinder Singh Gill ‘Kaala’— played by Paramvir Singh Cheema, the son of a farmer from Jalandhar— embarks on a quest to find his parents’ killers, but this is no typical whodunnit.

“Kaala is a reference to the caste system that’s rampant in Punjab, despite the Sikh ideology of no caste,” said show creator Rohit Jugraj.

When Kaala confronts his mother’s side of the family over his parents’ assassination, one relative proclaims: “We would happily hang after killing her.”

Through Babita, CAT also highlights how caste violence in Punjab has driven many in the Dalit community to embrace Christianity. When her husband leaves her over her caste identity, she converts to Christianity.

In a particularly well-crafted scene, Babita crosses herself in prayer while her father pays respects to a photo of BR Ambedkar.

Tabbar, meanwhile, turns the lens on the personal within the political, exploring twisted notions of family loyalty and morality.

It tells the story of a Punjabi household that gets entangled in a web of murder and lies after mistakenly exchanging bags at a railway station with a stranger. The show dismantles the stereotype of the happy Punjabi family with its portrayal of deadly secrets lurking in ‘normal’ households and how turbulent political histories often haunt generations to come.

Mumbai in the backyard

It’s not only Punjabis or Sikhs who are fascinated by the complexities of Punjab. Neither Kohrra director Randeep Jha nor Chamak writer Jugraj belong to the state, for example.

However, these shows are giving a big boost to homegrown talent.

In Kohrra, almost all the junior actors are from Punjab. For Tabbar, said Ajitpal Singh, 80 per cent of the cast was from the state. And then there are the rising stars.

A prime example is Suvinder Vicky, who delivered standout performances in both CAT and Kohrra. In the former, he portrayed the prime antagonist Inspector Sehtab Singh, and in the latter, he played the embattled sub-inspector Balbir Singh solving a murder mystery.

“You cannot run a household with money earned from just theatre. You have to look for other acting jobs too, like ads or films. OTTs have helped a lot of actors,” Vicky told ThePrint.

Kohrra‘s resounding success has propelled Vicky to stardom, with authenticity as his signature. Despite not being a Sikh, he convincingly portrays one in both shows, avoiding stereotypes and embodying the human struggles at the core of his characters.

His achievements, including the Best Actor (Male) for a Drama Series at the Filmfare OTT awards, were not just a personal triumph but gave heart to other artists in the region

“He got his due now, after so many years of struggle. It also gives hope to theatre actors in Punjab,” said Cheema.

Thanks to the OTT boom, a thriving mainstream acting career no longer demands a move to Mumbai. Mumbai is also coming to Punjab. Actors are now more willing to bet on themselves.

“Young actors from Punjab DM me saying they too want to become an actor like me and audition, and want to know how to go about it,” said Kaur. “Things are definitely changing.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)